End of the Imjin War

The calm before another storm

At the end of October 1593, King Seongjo, after more than a year's absence, returned to the liberated Seoul. The sight before his eyes was terrifying: the capital, including the symbol of royalty, the Gyeongbokgung Palace, lay in ruins. High-ranking dignitary Yu Seongnyeon, who entered Seoul immediately after the Japanese left it, recalled:

They were skinny, weak and emaciated, their faces the same color as the ghosts. The weather at this time was very hot and humid, so that the dead bodies and horse carcasses that lay all over the city began to rot, and they emitted such a stench that passers-by had to plug their nostrils.

Despite the fact that Seonjo's power was restored in most of the kingdom, the country lay in ruins, and the treasury was empty. During this extremely difficult time, the king appointed Yu Sungnyeon, a childhood friend of Admiral Yi Sunsin, head of the State Council (Uijonbu), which corresponded to the position of prime minister. It was on his shoulders that the burden of restoring the destroyed country fell.

Considering that part of the country remained occupied, it is not surprising that the main priority of Yoo Seongnyeon's policy was to strengthen the Korean military.

First of all, the construction of fortifications was launched throughout the country, especially in its southern part. During the first invasion, attempts by the Koreans to stop the Japanese on the battlefield, or by defending major cities with meager forces, proved ineffective. Now the Korean government has relied on the construction of many mountain fortresses with stone walls, protected by nature itself and quite convenient for defense.

Another important step of the Korean government was the reform of the army, which began at the end of 1593 and was carried out with the active participation of Chinese military experts. To improve the quality of training and the formation of military units in the Korean capital, a special department was created Hulleon togam. Military units began to be grouped by type weapons: infantry (salsa), armed with spears and swords; archers (sasu); fire fighting troopsphosu), armed with muskets and cannons. Having experienced the power of modern handguns during the first Japanese invasion, the Koreans established their production in their kingdom.

Organizational changes have also taken place in the Korean navy. Lee Sunsin, who caused so many problems to the Japanese, was officially appointed commander of the Korean fleet of the three southern provinces - Gyeongsangdo, Jeollado and Chungcheongdo, and his colleagues - Lee Okki and Won Gyun from now on had to obey his orders. Having created a naval base on Hansando Island, the energetic admiral was actively engaged in the construction of new warships and the training of sailors.

As a result of Yoo Seongnyeon's efforts, the country gradually began to return to normal. It is likely that the government's success in improving the combat capability of the armed forces of Joseon could have been greater if not for the renewed infighting between the Eastern and Western factions in the court. Prime Minister Yu Seongnyeon was one of the most prominent representatives of the "Easterners" and, of course, had many enemies. However, he was too powerful a figure, and therefore his enemies chose a more modest target - Li Sunxing.

Another naval commander, Won Gyun, had his own ambitions and was not eager to obey Li Sunsin. Even during the repulse of the first Japanese invasion, relations between the two military leaders were distinguished by conflict. Won Gyun repeatedly sent false reports to the royal court that denigrated Admiral Lee. In turn, Lee Sunsin had a sincere dislike for Won Gyun, considering him a mediocrity, a drunkard and a liar. In his "War Diary", he gave an extremely unflattering assessment of Vaughn's human and business qualities:

Elsewhere he writes:

The situation was aggravated by the fact that Yi Sun-sin, who tried to stay away from court intrigues, was nevertheless considered a protégé of Yu Seong-nyeong, while his competitor was associated with the Western faction, whose leaders occupied a number of high posts in the court.

Soon, clouds began to gather over Admiral Lee's head, as Won Gyun's influential patrons increasingly raised the question of the unfairness of Lee Sunsin's promotion and offered to remove him from the post of commander of the fleet. Such an undercover fight did not promise anything good.

diplomatic farce

Meanwhile, between 1593 and 1596, the parties were negotiating peace. In the summer of 1593, while the Japanese were storming Chinju, Chinese envoys arrived in Japan. Toyotomi Hideyoshi kindly received them in Nagoya. Finally, the Chinese negotiators received a text with Hideyoshi's conditions. These demands were as follows: the head of the Ming dynasty marries his daughter to the Japanese emperor, China and Japan restore official trade relations, and the four southern provinces of Korea remain under Japanese rule. In addition, Hideyoshi demanded that the Korean prince and two high-ranking dignitaries come to Japanese soil as hostages. The Chinese were shocked, as such demands looked insulting and could not be accepted by Emperor Ming.

The Japanese envoy Naito Joan was supposed to take this letter to Beijing and receive a response from the emperor. However, the Chinese command delayed him. The envoy was given to understand that he would be able to get an audience with the emperor only if he presented a document in which Toyotomi Hideyoshi recognized himself as a vassal of the Ming dynasty.

As a result, the text of the letter was changed beyond recognition. In it, the Japanese ruler, relying on the mercy of the Son of Heaven, humbly asked for recognition as a devoted vassal of the great Ming Empire. Of course, Naito could not arbitrarily collude with the Chinese command and falsify the document. All this was done with the knowledge of some Japanese military leaders, primarily Konishi, who was the main negotiator on the Japanese side. Realizing the impossibility of victory, he sought to stop or at least freeze hostilities.

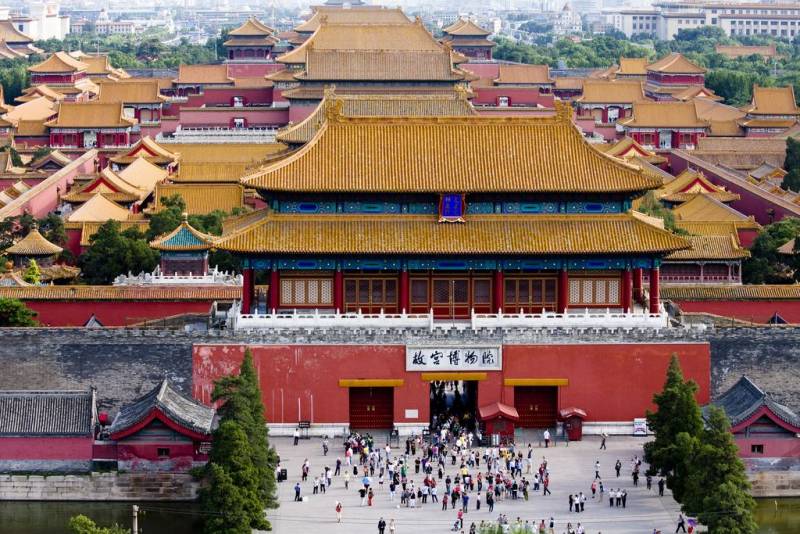

Imperial Forbidden City in Beijing. Modern look

Finally, the Japanese envoy was received by the Wanli Emperor in Beijing. What Naito said did not contradict the text of the letter. The Wanli Emperor graciously recognized Hideyoshi as his vassal and allowed him to send tribute to the court. At the same time, the ruler of Japan had to completely withdraw Japanese troops from Korea and promise never to encroach on it. The Japanese envoy bowed to the Son of Heaven and accepted all the demands. The Imperial Court began to prepare an embassy to Japan.

In the spring of 1595, the Chinese embassy began a long journey to Japan. However, the trip was on the brink of collapse, as the Ming ambassadors arrived in Seoul and announced that they would not travel to Japan until Japanese forces were withdrawn from the south of the Korean peninsula. The Japanese had to withdraw part of the troops from Korea. The Korean side reacted negatively to the negotiations, rightly believing that Toyotomi Hideyoshi had no good intentions towards Korea and China, but agreed to include its representatives in the delegation.

Finally, already in the following 1596, the Sino-Korean embassy set foot on Japanese soil. Hideyoshi hosted a grand reception for the guests at Osaka Castle. Before the reception, Toyotomi Hideyoshi dressed in a bright red silk outfit sent to him and a headdress, indicating a subordinate position. Hideyoshi, a brilliant military leader, did not understand the intricacies of Chinese etiquette, and for obvious reasons, there were no people willing to open his eyes to what was happening.

At first, the reception was friendly, but when the Wanli letter was translated into Japanese and read to Hideyoshi, the latter's face turned purple. The Son of Heaven graciously agreed to forgive Hideyoshi for invading Korea and recognize him as the van (king) of Japan and his vassal. Of course, there was no question of any trade privileges or territorial acquisitions for Japan.

Angered by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he expelled the Chinese ambassadors and began to prepare for the resumption of hostilities.

Castle in Osaka. Modern look

Return of horror

The purpose of the second invasion of Hideyoshi's troops into Korea was much more modest than the first time. If a few years earlier the ambitious ruler had dreamed of conquering the Ming Empire itself, now the Japanese were ready to be satisfied with the capture of the southern provinces of Korea.

The Japanese ruler drew conclusions from the defeats of his fleet at sea. This time, he assembled a much more powerful military fleet than before. Many new warships were built, well armed with guns and highly manoeuvrable. Moreover, the Japanese began to build ships similar to Korean kobuksons.

Despite the fact that the Japanese made great progress in increasing the combat capability of their fleet, among the Japanese naval commanders there was still no figure capable of fighting on equal terms with Li Sunsin. Consequently, the neutralization of the most talented of the Korean fleet commanders became an urgent need for the Japanese leadership. The Japanese resorted to intrigue.

Konishi Yukinaga assigned a certain Yojiro to carry out this mission. He informed the Korean command about the desire of his master to destroy his rival Kato Kiyomasa and reported on the route of this daimyō. Yojiro, on behalf of his patron, offered to ambush the Korean fleet at sea and destroy the hated Japanese commander. Having received this information, the royal court easily believed her and decided to act on the advice of Konishi in order to prevent the landing of Japanese troops in Korea.

Kwon Yul, the winner at Haengju, by that time appointed the commander-in-chief of the Korean troops, personally arrived on the island of Hansando and gave the order to attack to Lee Sunsin. But Admiral Lee, rightly suspecting deceit, refused to go to sea and thereby violated the order.

Soon Yojiro reported that Kato Kiyomasa had landed safely on the coast. Li Sunsin was accused of inaction and disobedience to orders, which led to the dismissal and arrest of Korea's best naval commander. Enemies of Li Sunsin ensured that the admiral was sentenced to death. Only the intercession of the Eastern faction and past merits saved him from death. Nevertheless, Lee was removed from business and demoted to the rank and file. Instead, his enemy Won Gyun became the commander of the Korean fleet. The success of the Japanese exceeded all expectations, as their most dangerous opponent was taken out of the game.

In March 1597, new Japanese troops began to land in Korea. Unlike the Blitzkrieg of 1592, the Japanese troops did not rush into an immediate attack on Seoul. For several months they were building up forces in the extreme south of the peninsula. In total, 121 soldiers were transferred from Japan to Korea. Another 000 troops were garrisoned in the coastal fortresses of the wajos. Thus, the new invading army was only slightly outnumbered by the one that had invaded Korean soil five years earlier.

By building up their forces, the Japanese waited for the start of the harvest season in Korea. Seizing the crops from the Korean peasants would greatly simplify the problem of supplying the huge invading army. For the same reason, Hideyoshi planned to launch an offensive in the southwestern province of Jeollado, which served as the breadbasket of the Joseon kingdom.

In the meantime, the Korean high command pressed Won Gyun to go to sea and fight the Japanese in order to stop the delivery of reinforcements to the Japanese land army. Being a drunkard and a schemer, the new commander of the fleet still understood that the Korean fleet was in danger of being trapped and demanded that the ground army support the fleet with their offensive. However, the command was confident in the power of the Korean fleet and ordered Won to march on his own. Finally, unable to withstand the pressure, Won Gyun at the end of August 1597 led the Korean fleet of more than 200 ships to the east.

On August 20, at the mouth of the Naktong River, not far from Busan, Won Gyun ran into the main body of the Japanese fleet of more than 500 ships. The day was drawing to a close, and after a long journey, the Korean sailors were tired, hungry and thirsty. In addition, the Japanese fleet far outnumbered the Korean in numbers. Despite such unfavorable circumstances, Won Gyun gave the order to attack. This time, the Japanese acted in the style of Yi Sunsin, launching a feigned retreat. The Koreans began to pursue the enemy and were under attack by the Japanese armada. 30 Korean ships were destroyed or captured, the rest of Won Gyun's fleet turned into a disorderly rout.

The defeated Korean fleet retreated to the Chilchongnyang Strait north of Geojedo Island. Won Gyun was inactive for a whole week, refusing to withdraw the fleet to a safer place. Commander-in-Chief Kwon Yul, extremely dissatisfied with the defeat and heavy losses, came to Won, scolded him and hit him, which was a humiliation for the admiral. After that, Won Gyun became depressed and went on a drinking binge, and at the decisive moment the fleet was left virtually without a commander.

Meanwhile, the Japanese command did not waste time. At midnight on August 28, the Japanese fleet unexpectedly entered the Chilchongnyang Strait. The night gave the Japanese the opportunity to covertly approach the Korean ships in order to board them. The Korean sailors, left without a commander and not accustomed to night battles, did not put up serious resistance. In the battle, Li Okki, a loyal comrade of Li Sunxin, and many other capable commanders were killed. Won Gyun himself fell at the hands of the Japanese.

Thus, due to the passivity of the commander in the battle in the Chilchongnyang Strait, the Korean fleet was destroyed. It is also important to note that almost the entire command staff of the Korean naval forces perished in the battle. The only high-ranking commander who survived this battle was Bae Sol, commander of the flotilla of the right half-province of Gyeongsangdo. At the very beginning of the battle, he ordered the 12 ships under his command not to engage the Japanese and retreat. The rest of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese. Subsequently, Bae Sol's act was severely criticized, and the commander himself was accused of cowardice and resigned.

When news about the catastrophe reached Seoul, King Songjo took the only possible decision in this situation, ordering the reinstatement of Yi Sun-sin as commander-in-chief of the fleet. Admiral Lee faced the impossible - to stop the Japanese fleet, which numbered several hundred ships.

March on Seoul

Having gained dominance at sea, the Japanese launched large-scale military operations on land. In September 1597 they launched an offensive to the north. The 20-year-old Kobayakawa Hideaki, the adopted son of the recently deceased Kobayakawa Takakage, who distinguished himself during the first invasion of Korea, was appointed nominal commander of the Japanese army.

The Japanese advanced with the forces of two armies: the Left Army under the command of Ukita Hideie (49 people) and the Right Army under the leadership of Mori Hidemoto (600 people). This time, the actions of the Japanese were extremely cruel. Of course, during the invasion of 65, the atrocities of the Japanese troops took place, but they occurred contrary to the order of Hideyoshi to spare the civilian population. This time, the Japanese ruler, enraged by the stubbornness of the Koreans and the humiliation of the Ming, ordered to betray everything to fire and sword. Carrying out cruel terror, the invaders spared neither children, nor the elderly, nor women.

Japanese atrocities. Jung Jae Kyung painting

A grim monument to Japanese brutality is the Mimizuka Mound, the so-called Ear Grave in the imperial capital of Kyoto. It is believed that the ears of 38 Korean and Chinese warriors, as well as civilians killed during the invasion of 000-1597, are buried in it. In reality, it was not the ears that were buried there, but about 1598 noses cut off by the Japanese from the dead enemy soldiers. If earlier the main proof of military prowess for the samurai was the severed head of the enemy, now they began to cut off the noses of the killed opponents, salt them and send them home, not forgetting to document their terrible trophies.

Mimizuka is the "grave of the ears" in Kyoto. Modern look

The first major land battle of this war took place near the city of Namwon. Nearly 50 Ukita Hideie's army laid siege to this city, which was defended by 3 Chinese soldiers under the command of Yang Yuan and 000 Koreans. The siege of Namwon lasted four days and ended with the capture of the city. Yang Yuan, wounded twice by a musket, managed to escape the city with less than 1 fighters. The rest of the garrison, as well as civilians who sought salvation outside the city walls, were exterminated.

Following Namwon, the large Korean city of Jeonju fell without a fight: its 2-strong Chinese garrison, which refused to come to the aid of the besieged Namwon, retreated to the north. The Japanese were successfully advancing north, and panic began again in Seoul. But soon the situation changed.

The commander of the Chinese military contingent left in Korea after the withdrawal of the main forces of the Ming army, Ma Gui led a small detachment against the Japanese. Near the town of Chiksan, 70 km south of the Korean capital, he fought the vanguard of the Japanese Right Army, commanded by Kuroda Nagamasa. The battle went on all day and did not bring a decisive victory to either side. The next morning, a 2-strong detachment of Ming cavalry came to the aid of the Chinese, which tipped the scales in favor of the Ming troops. The Japanese were repulsed and retreated.

Chinese Ming dynasty cavalry

The success of the Chinese near Chiksan stopped the further advance of Hideyoshi's troops on Seoul. Having learned that a huge Ming army was coming to the aid of Korea, and also taking into account the onset of cold weather, the Japanese command withdrew its troops to the southern coast of Korea, placing them behind the walls of the forts built by the Japanese. From that moment on, the main events that decided the outcome of the war took place at sea.

"Miracle at Myeongnyang"

At the time of his reinstatement, Lee Sunsin had only 13 ships under his command. They were the pitiful remnants of that mighty fleet that had defeated the Japanese at Hansando a few years earlier. Nevertheless, the very fact of the return of the naval commander undoubtedly inspired both the Korean sailors and the population in the south.

First of all, Lee Sunxing took up the task of restoring order: all the arsenals and warehouses were taken under guard, cowardly local officials were removed from their posts, and many officers were subjected to corporal punishment for negligent performance of duties. Thanks to such harsh measures, the naval commander was able to restore his authority and restore order.

In preparation for the battle with the Japanese, the admiral ordered all 13 remaining ships to be converted into kobukson. Having received a report about the approach of the main forces of the Japanese fleet, he retreated to the west, to the coast of Chindo Island. A Japanese squadron of 13 ships attempted to destroy Li Sunsin's forces, but the Koreans repulsed the enemy attack without much difficulty.

Over the next few days, the admiral, while waiting for the main enemy forces to approach, carefully studied the features of the waters surrounding Chindo Island, including the speed of the currents, the time of the tides. Choosing the place of the battle, he stopped at the Myonnyang (Myonryang) Strait, which separated the island of Jindo from the mainland. Behind him lay the Yellow Sea, where the Japanese were so eager to get. The choice of the battle site was ideal: at its narrowest point, the width of the strait did not exceed 250 m, and the current in it was extremely fast. Thus, the natural features of the Myeongnyang Strait did not give the Japanese the opportunity to realize their overwhelming numerical superiority.

Having received news of the approach of the enemy armada, the admiral removed his ships from the anchorage and stood with them in the open sea north of the strait. Along with the warships, many boats filled with refugees retreated. In an effort to create the illusion of the enemy's large fleet, the admiral ordered these boats to be placed behind the warships.

On the night before the battle, Yi Sun-xing gathered his captains to give them orders, and uttered the famous words:

And added that

At dawn on October 26, 1597, the Japanese armada approached the Myeongnyang Strait. If the size of Li Sunsin's fleet is unanimously estimated in various sources at 13 ships, then the size of the Japanese fleet is not exactly known and is determined in various sources from 130 to 330 ships. The maximum figure is indicated in the military diaries of Li Sunsin. At the same time, the Japanese edition of Li Sunsin's Drafts of War Diaries gives a figure of 130 ships. Probably, the minimum figure refers to warships directly involved in the battle, while the maximum takes into account all Japanese ships, including non-combat ones. At the same time, the fact of the colossal superiority of the Japanese fleet over the Korean in terms of the number of ships is not disputed by anyone.

As Li Sunxing expected, the huge Japanese armada did not have the opportunity to enter the strait in full force, which forced the Japanese commanders to divide their fleet into several separate squadrons. When the first Japanese ships passed through the strait and found themselves on the high seas, the Korean admiral gave the order to attack. The Japanese did not expect to meet the Korean fleet here and were confused for some time. The Koreans unleashed cannonballs and fiery arrows on the enemy ships. The flagship of Li Sunsin attacked the enemy, but soon found himself in a difficult position. In the War Diary, Admiral Lee describes the situation as follows:

The admiral's ship was surrounded. However, Lee's iron determination managed to turn the tide. Encouraging his people and threatening the death penalty to the captains of other ships, the admiral forced them to fight not for life, but to the death. One by one, the Korean ships rushed towards the enemy. Despite the colossal numerical superiority of the enemy, the Korean ships destroyed the Japanese ships, shooting them from artillery or ramming them with their bows.

Admiral Lee Sunsin. Shot from the film "Myungnyang" (South Korea, 2014)

Soon the tide began to rise, the direction of the current changed, and it began to carry Japanese ships to the southern part of the Myonnyang Strait. The Japanese fleet fell into disarray, some ships crashed into each other and sank. At that moment, the Koreans attacked the enemy and put him to flight. According to Li Sunsin himself, 31 Japanese ships were destroyed. As in all his previous battles, the Korean naval commander did not lose a single ship.

The Japanese failed to break into the Yellow Sea and support the offensive of their ground forces. Moreover, the fear of the victorious Li Sunsin was so great that the Japanese never tried to take revenge for the defeat at Myeongnyang, although they still had enough warships left.

Lee Sunsin, after the victory, vigorously set about restoring the naval power of Joseon, building dozens of new ships in a short time.

ulsan cul-de-sac

In November 1597, Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered the army to be withdrawn to the far south. The large Chinese army, which arrived to help Korea, joined with the Korean troops, after which the allied forces launched a counteroffensive.

To protect their foothold in the Busan area, the Japanese built a 200-kilometer defensive line, consisting of 14 forts. In December, Kato Kiyomasa arrived in Ulsan, located in the east, having recently ravaged the city of Gyeongju, the former capital of the ancient Korean kingdom of Silla. Expecting the arrival of the Chinese from day to day, Kato began to build a wooden fortress Tosan on a hill near Ulsan.

On January 29, 1598, an allied army approached Ulsan, numbering 40 Chinese soldiers under the command of the military leaders Ma Gui and Yang Hao and 000 Koreans under the leadership of Kwon Yul. At first, luck favored the Allies: with the help of a feigned advance, the Ming cavalry was able to lure the Japanese garrison out of Ulsan and defeat it. 10 Japanese died in this battle, and the city was taken. The surviving Japanese soldiers took refuge in the fortress of Tosan on a hill.

By the time the Chinese approached, construction work had not been completed, and the Japanese did not have time to complete one of the gates. Seeing a gap in the enemy defenses, the Chinese and Koreans the next day struck in this place and broke into the territory of the fort. Most of the provisions prepared by the defenders were captured by the allies. But the Japanese commanders were preparing for this scenario and, in addition to the outer wall, built a fortress inside. The Japanese soldiers retreated under the protection of its walls and managed to repel the attack of the allied forces, inflicting heavy losses on them.

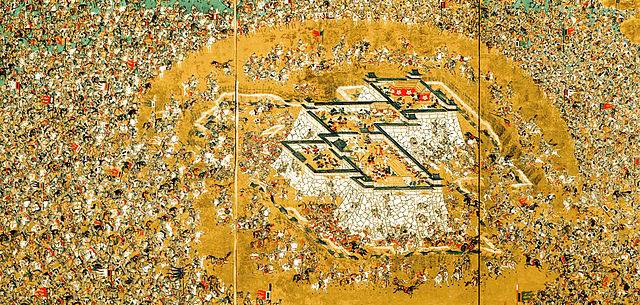

Japanese depiction of the siege of Tosan

The unsuccessful assault prompted the Chinese and Koreans to proceed to lay siege to the fortress, which was quite reasonable given the desperate situation of the defenders. With less than 10 fighters, Kato Kiyomasa had to face an opponent 000–5 times superior. The Kato people had almost no food supplies, they had little water. Moreover, there was little firewood in the fortress, which means that the Japanese suffered severely from the cold. In the face of food shortages, the Japanese commander ordered that most of the food available in the fortress be given to musket shooters as the most valuable fighters, while the rest had to get their own food.

On cold February nights, more and more Japanese soldiers came out of the fortress to get water or at least some food. Many of them died or were captured. So, in just one night, the Koreans captured 100 Japanese. The proud warriors of the Land of the Rising Sun were so exhausted by hunger and thirst that they often surrendered to the enemy without resistance.

It seemed that the fall of Tosan was only a matter of time. However, the defenders soon received outside help. The Japanese squadron entered the mouth of the Tehwa River and approached Ulsan from the south, forcing the Chinese command to transfer part of the artillery to contain it. Detachments of Japanese commanders from other fortresses also came to the rescue. Not daring to enter into battle with the numerically superior allied forces, the Japanese, having occupied the surrounding hills, placed many banners on them, thereby exerting a psychological impact on the enemy. The Chinese commander Yang Hao began to get nervous, because in the event of a combined attack by the Japanese forces, his army would already be in a difficult position.

In addition, the Allies suffered from the cold no less than the Japanese. Do not forget that the fighting took place in February, which created problems with fodder for horses. The supply situation was also difficult. Under these conditions, Yang Hao had only to take the fortress by storm or retreat.

The Chinese commander chose the first. At dawn on February 19, 1598, the combined Korean-Chinese army launched an assault on the fortress. The people of Kato, exhausted and hungry, strained their last strength and were able to repel the assault, destroying 500 Chinese and Koreans.

Fearing the arrival of a sizable Japanese force, Yang Hao ordered a retreat. Seeing the withdrawal of the enemy, the Japanese, who were on the ships, went ashore and rushed to pursue the retreating enemy. The situation was aggravated by the fact that the Korean troops did not receive an order to retreat and were in confusion. Abandoning their weapons and armor, the Chinese and Korean soldiers fled. The defeated allied army rolled back to Gyeongju.

S. Hawley estimates the losses of the Chinese and Koreans during the three weeks of the siege of Ulsan in the range from 1 to 800 soldiers killed. K. Svope considers the most plausible figure to be 10-000 thousand dead soldiers. At the same time, the losses of the Japanese were horrendous - less than 3 exhausted and hungry fighters remained from the 4th garrison.

The successful defense of Ulsan, more precisely, the fortress of Tosan, became a truly epic event for the Japanese. Fighting against a vastly superior enemy and suffering from hunger, thirst, cold and disease, the people of Kato Kiyomasa were able to survive, demonstrating high morale and the ability to fight not by numbers, but by skill. Nevertheless, the heroism of the Kato fighters could not change the strategic situation, which was not in favor of the Japanese.

Battle of Noryanjin

In the summer of 1598, troops arriving from China, supported by Korean detachments, launched a large-scale offensive in the south in three directions in order to throw the Japanese into the sea. The Korean fleet, which had grown significantly in numbers, also received replenishment - part of the Chinese fleet under the command of Chen Lin joined him.

On September 18, 1598, Toyotomi Hideyoshi died at the age of 62. The death of the architect of this war finally put an end to the attempts of the Japanese to gain a foothold on Korean soil. Before his death, Hideyoshi gave the order to withdraw troops from Korea. His son Hideyori was only five years old, making internal strife inevitable. Under these conditions, troops were needed in Japan, and not in Korea. The environment of the heir and the leading daimyo, including Tokugawa Ieyasu, also realized the impossibility of achieving victory and sought to end this war.

At the same time, fearing unpredictable consequences, the newly established Council of Five Elders concealed information about Hideyoshi's death for some time, and the Japanese continued to fight in Korea as if nothing had happened.

At the end of October 1598, the last major land battle of this war took place at Sacheon. The Japanese commander Shimazu Yoshihiro stationed an 8-strong garrison in a new fortress built by the Japanese near Sacheon. In Sacheon itself, he left only 500 soldiers. When the 29-strong allied army (26 Chinese and 800 Koreans) approached Sacheon, advancing in the central direction and led by the Ming commander Dong Yuan, he ordered the evacuation of the Sacheon garrison and gathered all the troops in a new fortress. On October 2, Sino-Korean troops launched an assault, suffering heavy losses.

In the midst of the assault, the Japanese launched an extremely successful sortie and inflicted a horrific defeat on the enemy. The defeated allied army rolled back from Sacheon. As Shimazu Yoshihiro later claimed, his people killed 38 enemy warriors. This figure looks very high, as it exceeds the size of the entire army of Dong Yuan. It is most likely that 700–7 Chinese and Korean soldiers died in the battle, i.e. a quarter of the army. The victors cut off the noses of the killed enemies, salted them and sent them to Japan.

Meanwhile, an allied army of 13 Chinese under the command of Liu Ting and 600 Koreans under the leadership of Commander-in-Chief Kwon Yul, advancing in the western direction, laid siege to Suncheon. Konishi Yukinaga, who defended it, also deployed his troops not in Suncheon itself, but in a fortress built by the Japanese.

After the allies set up camp near the walls of the fortress, the Japanese commander offered Liu Ting peace negotiations. The Chinese commander agreed, but it was only a military trick. Immediately after Konishi was to open the gate and leave the castle, the land army and navy under the command of Li Songxing and Chen Lin were to launch a combined attack. But the plan failed, because for some unknown reason, the artillery shelling of the castle began earlier, and the Japanese commander figured out the enemy's trick and ordered the gates to be closed. Over the next two weeks, the Chinese and Koreans continuously attacked the fort, but it remained impregnable.

Only in early November did the Japanese commanders in Korea receive news of the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and an order to evacuate troops from the Korean Peninsula. Konishi Yukinaga in Suncheon found himself in a difficult situation. The army of Liu Ting from the land and the Korean-Chinese fleet of Li Songxing and Chen Lin blockaded him in the fortress. In an effort to save his forces, Konishi Yukinaga attempted peace negotiations with the Chinese commander, remembering to accompany his letters with gifts. Liu was prepared to let the Japanese leave.

However, the allied fleet had its own command, and therefore Konishi began to actively “process” Chen Lin and Li Songxing, showering them with rich gifts. The Korean admiral objected vehemently to allowing the Japanese garrison to escape. But his Chinese counterpart was not so belligerent and allowed one Japanese boat to leave the bay.

In this way, Konishi Yukinaga was able to contact the commanders of the other fortresses and request their support. A fleet of 500 ships under the command of Shimazu Yoshihira arrived to help Konishi.

The allied fleet consisted of 85 large Korean ships and 63 Chinese, of which 6 were heavy warships and 57 light ships. In other words, the Japanese fleet was outnumbered, but most of the ships that Shimazu Yoshihiro brought were light transport ships.

The last naval battle of the Imjin War took place in the Noryangjin Strait, through which the Japanese fleet moved towards Suncheon. On December 17, 1598, at 2:XNUMX a.m., Li Song Xing unexpectedly attacked the enemy. The Allied fleet operated in three squadrons: the right flank was commanded by Li Songxing, the center by Chen Lin, and the left flank by another Chinese, Deng Jilong. During the battle, Chen Lin's flagship was attacked by Japanese ships and was surrounded. The Chinese admiral literally had to fight not for life, but for death. In a boarding battle with the Japanese, his son was wounded.

Seeing the danger that threatened Chen, Deng Jilong with a couple of hundred fighters rushed to his aid. However, he suddenly came under friendly fire. The ship was damaged, which allowed the Japanese to board it. Dan and his men died a heroic death.

Meanwhile, Li Sunxing successfully attacked the Japanese, burning and sinking enemy ships. Only one flagship of Li Sunsin destroyed 10 Japanese ships. The admiral himself was in the thick of the battle, shooting at the enemies with a bow. The success of this attack forced the Japanese ships surrounding Chen Lin's ship to retreat.

Dawn has come. Having suffered huge losses, the Japanese began to retreat, and then Li Sunsin gave the order to pursue. As the Korean fleet caught up with the retreating Japanese, a bullet fired from a Japanese arquebus hit him in the chest. Feeling the approach of death, the admiral gave the last order:

A few minutes later, the victorious naval commander died. Nevertheless, the battle ended in the defeat of the Japanese fleet: according to Sonjo Sillok, about 200 Japanese ships were burned or sunk, and another 100 were captured. According to other data cited by S. Turnbull, the Japanese lost 450 ships.

Death of Lee Sun-sin

However, despite horrendous losses, Shimazu Yoshihiro was able to achieve his goal - he diverted the forces of the Sino-Korean fleet, which allowed Konishi Yukinaga's troops to evacuate Suncheon.

In the last days of December 1598, all Japanese detachments left Korea. The bloody military conflict is over.

Aftermath

At the end of the XNUMXth - beginning of the XNUMXth centuries. the Japanese army was the best in East Asia in terms of organization, technical equipment, and especially individual combat training of personnel. It was led by commanders who possessed great personal courage and tactical skill and who had vast military experience gained during the years of internecine wars in Japan. Nevertheless, the war ended with the complete collapse of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's plans.

What is the reason?

Starting this war, the Japanese ruler clearly underestimated the enemy - China and Korea, which led to a number of failures already at the first stage of the war.

Firstly, the Japanese fleet turned out to be clearly weaker than the Korean one, and in the face of Admiral Lee Sunsin, the Japanese found an extremely dangerous enemy. The tactical skill of Li Sunsin made it possible to thwart the plans of the Japanese both at the first (1592-1593) and at the second (1597-1598) stage of the invasions. By cutting off the supply of the Japanese army by sea, the Koreans nullified all Japanese successes on land. The legendary admiral, who during his lifetime repeatedly suffered from injustice on the part of the court, after his death was awarded all kinds of honors and quite rightly began to be considered the savior of Korea.

Secondly, the people's war became an unpleasant surprise for the Japanese. If in Japan itself war was considered the work of the samurai, while the common people remained passive, then in Korea, many ordinary people and even Buddhist monks took up arms. Although the poorly armed detachments of the Korean militias were often defeated, they diverted a significant part of the Japanese troops, which prevented the establishment of firm control over the occupied territories by the Japanese.

The mountainous terrain of Korea favored guerrilla warfare, and the organization and combat effectiveness of the popular resistance forces gradually grew, which made it possible to deliver sensitive blows to the Japanese. The Koreans gradually learned to resist a stronger opponent. If most of the field battles were won by the Japanese, then the actions of the Koreans in protecting the fortresses were quite effective, as evidenced by the defense of Henju in 1593 and Chinju in 1592 and 1593.

Thirdly, an important role in repelling the Japanese invasion, especially in 1597–1598, was played by the intervention of Ming China. Given the close relationship between Korea and China, as well as Toyotomi Hideyoshi's intentions towards the latter, the Wanli Emperor's decision to send a sizable army to Korea's aid was quite logical.

Despite the fact that the Chinese troops were repeatedly defeated in battles with the Japanese, the allied forces were able to achieve numerical parity and then superiority over the Japanese, which, coupled with the actions of the fleet and Uibyon detachments, made the Japanese victory in the war impossible. Toyotomi Hideyoshi himself understood this, giving the order before his death to return the Japanese troops home. Failure of the Japanese invasion of Korea 1592–1598 had serious consequences for all countries involved in the conflict.

In 1600, the Japanese daimyo Tokugawa Ieyasu, who at one time prudently evaded participation in the Korean adventure, defeated his opponents in the greatest stories Samurai Japan Battle of Sekigahara. From that time on, for two and a half centuries, Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shoguns. A long-awaited time of peace and stability has come for a country that has lived for centuries in internecine wars.

With the coming to power of Tokugawa Ieyasu, Japanese-Korean negotiations began on the normalization of relations. From the Japanese side, they were led by So Yoshitoshi, the ruler of Tsushima, which is not surprising: the well-being of the island and the So house was most directly related to trade with Korea. In 1609 diplomatic relations and trade were restored.

Having won, China and Korea were seriously weakened by this war. This is especially true of Korea, on whose territory the fighting took place. The country managed to defend its independence, but at an extremely high price - the number of arable areas decreased significantly, the craft was in decline. Many temples, palaces and libraries were destroyed by the invaders. For China, the war over Korea also resulted in large human and financial losses.

A few decades later, both countries were unable to oppose anything to the warlike "northern barbarians" - the Manchus. In 1644, the Ming dynasty collapsed as a result of the peasant war and the Manchu invasion. The winners founded a new dynasty - the Qing. The Manchus invaded Korea twice, until in 1637 the Joseon finally recognized themselves as tributaries and vassals of the Qing.

However, the Qing emperors, like their Ming predecessors, did not interfere in the internal affairs of Korea, and it retained its sovereign statehood. The ruling circles of Korea began to pursue a policy of self-isolation of the country, maintaining limited contacts only with China and Japan.

Korea remained in the position of a "hermit country" until the second half of the XNUMXth century, when, in the conditions of the military and economic rise of Japan as a result of the Meiji reforms, the Japanese rulers again turned their eyes to the Korean Peninsula. However, that's another story.

References:

1. Asmolov K. V. The Imjin War and the Korean Warrior of the 3th–XNUMXth Centuries. http://world.lib.ru/k/kim_o_i/imkXNUMXrtf.shtml

2. Iskenderov A. A. Toyotomi Hideyoshi. M., 1984.

3. History of Korea. T. 1–2. M., 1974.

4. Kurbanov S. O. A course of lectures on the history of Korea. St. Petersburg, 2002.

5. Lee Sun-sin. (Nanzhong ilgi) / intro. st., trans. from hanmun, comment. and adj. O. S. Pirozhenko. M, 2013.

6. Pastukhov A. M. Kobukson - myth or reality? [Electronic resource] // History of military affairs: research and sources. - 2015. - Special issue III. Naval history (from the era of the great geographical discoveries to the First World War) - Part II. – C. 237–277 (12.10.2015).

7. Complete collection of documents of Lee Sunsin (Lee Chungmu Gong Chongseo) / intro. st., trans. from hanmun, comment. and adj. I. I. Khvana, ed. O. S. Pirozhenko. M, 2017.

8. Prasol A.F. Unification of Japan. Toyotomi Hideyoshi. M., 2016.

Statsenko A. Samurai Tamer. https://warspot.ru/3102-ukrotitel-samuraev.

9. Michael Heskew, Christer Jorgensen, Chris McNab, Eric Nydrost, Rob Rice. Wars and battles of Japan and China: 1200-1860 / transl. from English. O. Shmeleva. M., 2010.

10. Hawley, Samuel: The Imjin War. Japan's Sixteenth-Century Invasion of Korea and Attempt to Conquer China. Seoul, 2005.

11. Swope, Kenneth. A Dragon's Head and Serpent's Tail. Ming China and the First Great Asian War, 1592–1598. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 2009.

12. Turnbull, Stephen. Samurai Invasion. Japan's Korean War, 1592–1598. Cassell, 2002.

Information