"Moscow, burnt by fire". Background of the tragedy

The grandiose fire that practically destroyed Moscow in September 1812 shook the imagination of contemporaries both in Russia and abroad. The painful memory of him was preserved even in the time of Lermontov, a line from whose poem became the title of the article. At present, few people imagine the scale of work to restore the burnt city. Most people believe that Moscow was reborn very quickly and literally on its own.

Meanwhile, construction work in Moscow after 1812 can be compared (and compared) only with the construction of St. Petersburg from scratch. The restoration of the city continued until 1843, when the State Commission for the Construction of Moscow finally finished its work. Lermontov's famous poem "Borodino" had already been published (in 1837), and the poet himself died in 1841, and Moscow had not yet been fully rebuilt after that fire. Only at the first stage, a huge amount of 5 million rubles was allocated from the state treasury for restoration work. Since Alexander I, who wanted to please the "civilized Europeans", refused reparations and compensation, depriving Russia of all the fruits of many years of hardest wars against Napoleonic France, Moscow had to be rebuilt at the expense of Russian peasants. Five new factories were built for the production of bricks, and soldiers stationed near Moscow took an active part in the construction of new buildings. At the same time, by the way, (in 1819) the bed of the Neglinka (Neglinnaya) River was blocked with a brick vault, through which the Kuznetsky Bridge was once thrown, and it was she who once separated the Kutafya tower of the Moscow Kremlin from Troitskaya.

But why did Moscow burn down at all? After all, the Russians were by no means going to surrender it, and Napoleon, even in a dream, could not imagine that he would ever occupy this city.

Bonaparte's plans

Starting a war with Russia, the French emperor was not going to destroy the Russian state, dividing it into several parts, or conquer Russia, or even change the ruling dynasty. Jean-Baptiste Marbeau stated:

Napoleon himself said to Berthier:

When planning the campaign of 1812, Bonaparte called it the "Second Polish War" (the first was in 1807) and expected that it would end after several frontier battles. He said then:

In Vilna, Bonaparte, by the way, having crossed the Neman, was delayed for 18 days, but did not create any Lithuanian state, as he understood that this would complicate peace negotiations. Lithuania, which the Poles were eager to get, Napoleon intended to return to Alexander in exchange for additional concessions. That is, he was going to act like Peter I, who, in his own words, during the Great Northern War, ordered to occupy Finland only in order to later exchange it for something more necessary.

For decades, there have been disputes about why Napoleon went towards Moscow. Apocryphal anecdotes about his reasoning, they say, if he "will occupy Kyiv, hit Russia in the legs, Petersburg in the head, and Moscow in the heart”, cannot and should not be taken into account. It must be understood that in those days Moscow was a city of retired nobles, nostalgic for the years of previous reigns. Great politics and great careers were made in St. Petersburg, where Moscow old men in old-fashioned camisoles were treated with irony and even with outright mockery. Moscow at the beginning of the XNUMXth century was just a large provincial city and had practically no political significance (and strategic, too). And one can hardly take seriously the words of Napoleon, which he told the envoy of Alexander I Balashov - that he would sign a peace treaty in Moscow. In the mouth of the emperor, this is clearly a “figure of speech”, which was supposed to frighten and emphasize the seriousness of intentions. Bonaparte had no real plans to occupy Moscow.

But the movement to St. Petersburg was more promising. It created a direct threat to Alexander I and the highest aristocrats of the empire. In the event of a real danger, they, regardless of the wishes of the emperor, would certainly demand that he enter into negotiations with Napoleon. And these people knew how to "persuade". The “weak and crafty” Alexander, the grandson and son of the murdered emperors, was well aware of the “stranglehold” that “limits the autocracy in Russia.” The secret evacuation of the jewels of the imperial family to the city of Vytegra in the Olonets province testifies to the tsar's fear of Bonaparte's attack on St. Petersburg. Here they stayed until the spring of 1813.

Some argue that the movement to Petersburg called into question the supply of food and fodder to the huge army, since the terrain here was less fertile. However, the non-chernozem lands of Belarus and the Smolensk province could not boast of rich harvests, and, as we know, they did not provide for the needs of either the Great Army of Bonaparte or the Russian army pursuing it, which eventually suffered huge non-combat losses on the way to Vilna, comparable to French. Therefore, if supply issues are considered as decisive, Bonaparte should have gone in the direction of the black earth provinces of Novorossia. For the Russian Empire, the loss of the Black Sea coast was unacceptable, and the Russian troops themselves would have come even to Yekaterinoslav, even to Odessa. How several decades later they went to the Crimea - to the besieged Sevastopol.

The fact that the distance from Vilna to St. Petersburg is much less than to Moscow speaks in favor of the decision to move to the capital: 651 km versus 791 km in a straight line, and 721 km versus 901 km along the highway. And the supply of the Great Army moving along the coast could be organized by sea. Moreover, it is known that up to Moscow, Napoleon's Grand Army relied only on its supplies. So even to St. Petersburg they would be quite enough. In addition, it should be taken into account that in this case it would be necessary to attack not on the native Russian lands, but on “foreign regions”. Many Poles lived in Lithuania, and the local nobles were fairly Polonized. Russian agent Maxim von Fock reported that in Vilna, where Alexander I had recently danced at the ball,

And in Latvia and Estonia, the Baltic barons, whose ancestors once conquered these lands, maintained a strict order from ancient times. They retained their power over them in the Russian Empire. Napoleon could hope for a more loyal attitude of the inhabitants of these areas. And only one corps of Wittgenstein, numbering about 20 thousand people, covered St. Petersburg.

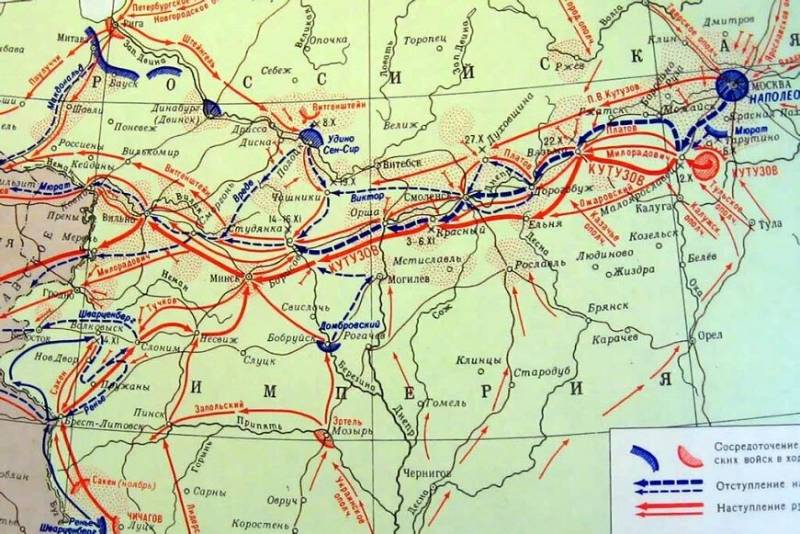

Karl Clausewitz believed that Napoleon chose the Moscow direction because the best road led to this city from the western borders. But after all, his army did not just move, but pursued the retreating Russian troops. It was they who determined the movement of the Great Army of Bonaparte. And therefore, based on the foregoing, the most plausible movement of Napoleon towards Moscow can be explained by his lack of a clear offensive plan. Bonaparte did not care where to go: he simply sought to give the Russians a general battle. And it didn't matter where exactly it would happen - near Riga, near Kyiv, or near Polotsk. He wanted to quickly defeat the Russian army and immediately make peace. Napoleon's troops followed the armies of Barclay de Tolly and Bagration, who, retreating, led him first to Smolensk, and then to Moscow.

Even before the start of the campaign, Bonaparte told the archchancellor of his empire, Jean-Jacques Cambaceres, that the war with Russia should continue for two years. During the first, a bridgehead along the Dvina and Dnieper should be prepared, after which the army should be placed in winter quarters. And in the second year, in the event of Alexander's refusal to make peace, continue the offensive.

Napoleon said the same to Metternich:

Suger claims that already in Vilna, Bonaparte said to General Sebastiani:

July 28, 1812 Emperor Napoleon says in Vitebsk:

But still sends the army to Smolensk. And not only generals and marshals, but also many officers, and then even privates, are increasingly beginning to look back and think about the future.

On Saint Helena, Napoleon wrote:

In general, everyone understood the perniciousness of continuing this campaign. And, of course, Bonaparte himself understood this. The French emperor saw that his army was weakening, leaving garrisons in the occupied cities, suffering huge non-combatant losses, and in the first month alone lost 20 thousand horses. He really wanted to stop the army in Smolensk.

Armand de Caulaincourt recalled:

The quartermaster of the Grand Army, General Philippe-Paul de Ségur, wrote:

Moreover, he claimed that already in Smolensk Bonaparte himself

Segur also reports on the conversation between Napoleon and General Duroc:

Unable to make a decision, Bonaparte stayed in Smolensk for 7 days. And the English General Wilson, who was at the headquarters of Barclay de Tolly, sent a letter to London with the words:

And after 4 days, having learned about the continuation of the movement of the Great Army, he sends another letter in which he joyfully reports:

As we can see, not only Barclay de Tolly, but also many French generals, and even the Briton Wilson, are aware of the destructiveness of Napoleon's movement towards Moscow. But for some reason, Bagration and some other Russian generals do not understand this, who accuse Barclay of betrayal and passionately desire to enter into a general battle with the superior forces of Bonaparte's Great Army. That is, to do exactly what the emperor of the French wants so much now. One involuntarily recalls the famous words of Napoleon, who claimed that in Russia in 1812 there were no good generals left, and Bagration was experienced, but stupid. However, Barclay de Tolly, already cursed by many, is unshakable and decided at the cost of his reputation to save Russia. And the specter of victory in the general battle with the escaping Russian troops beckons Bonaparte, promising the end of the war and the conclusion of the desired peace. Napoleon took a chance - nevertheless he gave the order to continue the attack on Moscow. His desire to win the war quickly, in one year, led the Grand Army to disaster.

Let's listen to Caulaincourt again:

Felician von Mirbach. Napoleon in Smolensk

The fate of Moscow

So, the Russian troops rolled back to Moscow, but the topic of the possible abandonment of this city was taboo. Even after the battle of Borodino, many were sure that another battle would be given, and Kutuzov's decision to leave Moscow came as a shock to everyone. These jingoistic moods, prevailing both in the leadership of the army and in the administration of Moscow, led to tragedy. There were no plans for evacuation, if not material, then at least historical values. Unexpected for everyone, the news of the surrender of the city led to panic and an exodus of both Moscow officials and citizens who had lost control over the situation.

Kutuzov, who to the last assured everyone that Moscow would not be surrendered, perfectly understood what the emperor's reaction would be. Moreover, he had already informed him of the victory at Borodino, having received 100 thousand rubles and the rank of field marshal. Therefore, in a letter dated September 4, having already left Moscow, the newly minted field marshal reassured the emperor:

In fact, huge reserves were left in Moscow weapons, food and fodder. Among other things, the French got 156 guns, 74 guns, 974 sabers, 39 gun shells. This is all the more strange because at the end of 846 there were only 27 rifles on average for one Russian battalion (about a thousand people). And even in 119, 1812 Russian soldiers out of every thousand were unarmed. Soldiers who did not get guns had to arm themselves at the expense of their dead comrades. What (apart from negligence and slovenliness) prevented at the end of August and the beginning of September 776 from opening the arsenal and taking at least guns, so that later they could be distributed to unarmed soldiers?

608 old Russian banners and more than 1000 standards were also left in Moscow. And it was already the greatest shame, for which no one has ever been held responsible.

The French also got huge stocks of noble estates, merchants' shops and some, but supplies of ordinary and humble people. On Saint Helena, Napoleon told Dr. O'Meara:

But not only houses, merchant shops and an arsenal were left, but also about 22,5 thousand wounded soldiers and non-commissioned officers (some authors write about 30 thousand). Yermolov later recalled "heartbreaking groans of the wounded, left in the power of the enemy". They are "entrusted to the philanthropy of the French troops”- and almost all died in the Moscow fire. Carl von Clausewitz wrote to his wife:

In general, the situation, frankly, was nowhere worse, and even the rank and file understood this. The extreme decline in the morale of the Russian troops, among others, is reported by such well-informed memoirists as N. N. Raevsky (commander of the VII Infantry Corps), S. I. Maevsky (head of Kutuzov’s office) and A. I. Kutuzov). The authority of the commander-in-chief reached its lowest point, and, according to A. B. Golitsin (Kutuzov’s orderly), from Moscow he “I left so that, as much as possible, I would not meet anyone". The passage of the army through the city on September 2 (14) was led by Barclay de Tolly, who spent 18 hours in the saddle.

The Governor-General of Moscow F.V. Rostopchin recalled that in the army then they did not hesitate to call Kutuzov "the darkest prince».

In the next article, we will talk about this interesting and peculiar person, whom Catherine II called "Crazy Fedka". The wife of this "Russian patriot", an irreconcilable fighter against French influence, according to E. Tarle, was "Frenchized Catholic". And his daughter married a relative of the quartermaster of Napoleon's Great Army, quotes from whose memoirs are given in this article. She became a well-known writer and is currently one of the five most popular authors of children's books written in French.

Postage stamps dedicated to Sophie de Segur, nee Sofya Rostopchina

Many consider F. Rostopchin the "Russian Herostratus", responsible for the fires that practically destroyed Moscow, but also became fatal for Bonaparte's Grand Army.

Information