Operation HUSH - the amphibious landing that did not take place

World War I, or the Great War as it was known, broke out in 1914 and brought the major European military empires into conflict: France, Britain, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire. As the war spread around the world, it eventually engulfed the United States and claimed millions of lives before being finally brought to an end in a series of peace treaties between 1919–1922.

The names of many battles and operations have entered the general lexicon, for example, Ypres, Verdun, Osovets or Brusilovsky breakthrough. But there are also lesser-known operations, including a British plan to launch an invasion (classified as a "raid") of the Belgian port of Zeebrugge.

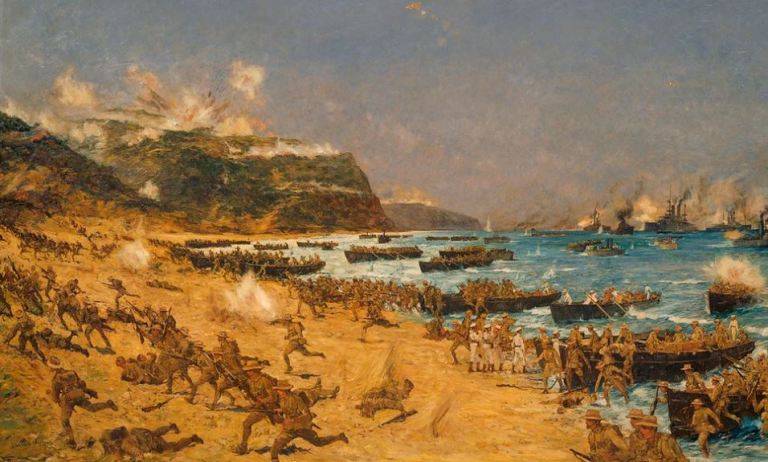

This was not to be a repeat of the unsuccessful landings at Gallipoli in 1915, which ended in complete failure. It was supposed to be an "raid" en-forte - a raid that would be supported by the new weapons wars - a tank. With the support of Sir Henry Rawlinson, commander of the 4th Army Corps, this bold undertaking was highly secretive, which was reflected in its code name - Operation Silence.

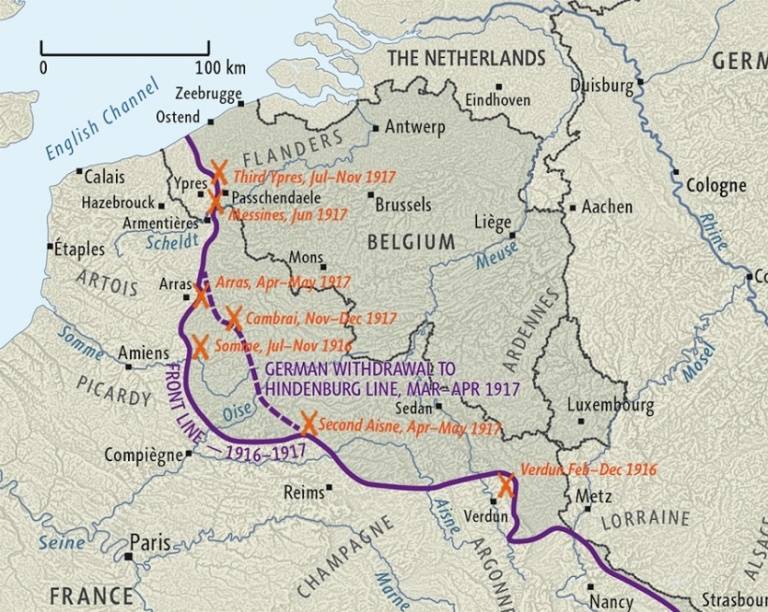

The plan for Operation Silence became an integral part of the Third Battle of Ypres, the British desire to capture the Belgian coast from the Germans. This would interfere with the German the fleet use Belgian ports as bases to attack and sink merchant ships carrying vital supplies to Britain.

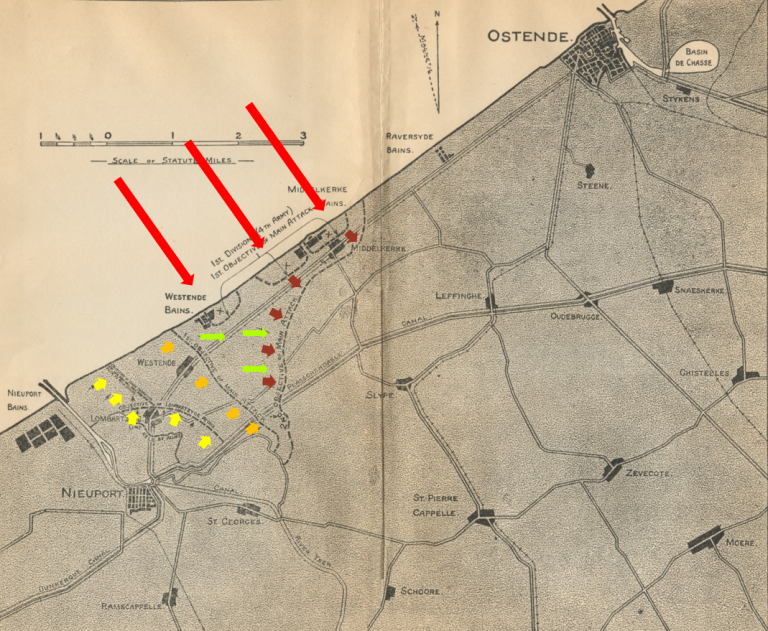

To this end, the Third Ypres plan called for an amphibious landing by the British 1st Division, supported by 9 Mark IV tanks (6 male, 3 female). Already on the coast, the forces advancing from Ypres connected with the landing force and moved along the coast together.

Admiral Bacon, reflecting in a note in 1917 on the need to attack the Belgian coast and make the harbors of Ostend and Zeebrugge out of German reach, wrote:

I have no hesitation in saying that if the Germans had real maritime instincts, they could, on any given day in the last two years, deliver a clean blow to our forces at the entrance to the English Channel, and until recently they could have sunk in one fell swoop from fifty up to eighty of our ships in the Downs. Moreover, they could repeat the operation more than once, and we would not be able to effectively retaliate.

Ostend and Bruges have two harbors where destroyers can be practically safe from attack. I previously explained the reasons for the impossibility of destroying these harbors. Large batteries installed by the Germans on the shore prevent the approach of our ships. They don't have shipping routes to protect since they can get all of their cargo by rail and therefore don't need to have any ships in the near future. Therefore, we have no target on which to strike.

On the other hand, we must protect our trade route to the Thames and our transport routes to Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne - all in the immediate vicinity of their harbors. To do this, we must constantly keep our forces on patrol at sea. In order for the detachment to constantly patrol, it is necessary that in the harbor, resting and repairing, there are larger forces than those that guard the sea. Therefore, if we must always maintain at sea a force equal in number to that which the enemy can send to attack us, we must detach and keep close by a force nearly three times as large as that which the enemy can send against us.

Such forces uselessly hold the same number of enemies, as he does not need to constantly keep his forces in southern waters. He can move them from Elba secretly and at will, and if their appearance is discovered, it must be pure coincidence.

In this way the enemy can knock us down and attack us with ships that do not need to stay here, but can operate in the north at will; it does not require ships to rest, as they simply raid and return to their base.

For the sake of safety, we must keep a force at sea sufficient to deal with his ships when they arrive, since in practice it is useless to consider ships as "auxiliary ships" when these ships are in the harbor, since they must leave the harbor, gain speed and arrive to the attacked place. In practice, before this can be done, the raid is over, the damage has been done, and the enemy is far from our harbors.

This is the punishment that we had to pay more than once during this war for allowing the enemy to establish strong naval bases near our main transportation arteries. Germans study daily; they have greatly improved in naval initiative; and soon we can expect similar troubles.

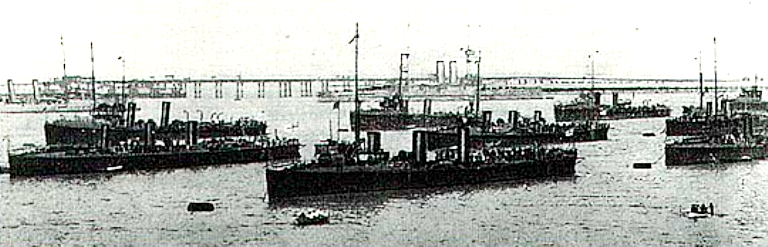

The Dover Patrol, as it was known from the harbor of the same name, was an important formation of the Royal Navy during the war. This flotilla was primarily responsible for ensuring the free passage of British and Allied merchant and military ships across the English Channel to the North Sea, protecting trade routes in the Atlantic from German coastal raiders and submarines.

Equipped with many ships, it was a sizable navy, consisting of just 12, at the start of the war, a few ancient and mostly obsolete Tribal-class destroyers. But it soon expanded into an army with vessels ranging from cruisers to its own submarines, and had air support in the form of propeller-driven aircraft and airships.

In April 1915 Vice Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon took command of the patrol. The work of the patrol was difficult, given the lack of radars, sonars and many other devices and other equipment, including for trawling and anti-submarine work, at first. As the war progressed, the patrol would eventually take the lead in blockading German-held Belgian ports to simply prevent German ships and U-boats from leaving or arriving - an easier solution than hunting them on the high seas.

Zeebrugge

The Germans invaded Belgium in August 1914 and quickly occupied most of the country, leaving only a small part in the west free and unoccupied. The front line formed by the Belgian, British and French defenses, primarily around the salient at Ypres, became a crypt during the war, the scene of many years of bitter fighting and little progress in the liberation of Belgium, despite huge casualties.

The two main ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge on the Belgian northwest coast gave the German occupying forces direct access to the North Sea, from where ships and submarines could harass Allied ships sailing from the US and Canada to Britain and from Britain to France.

This narrow corridor, about 50 km wide on the coast, with two key ports, located just behind the German front line, was a very tempting target for landings. Theoretically, an attack on one of these ports would not only deprive the German naval forces of a base, but, if successful, could easily turn into a new front around the stagnant extreme northern lines of the Western Front.

From August 1915 to March 1916, various periodic bombardments of the indicated harbors by the Dover Patrol were carried out, but the Germans remained in safe shelters. Due to the ineffectiveness of bombardments, blocking by mines and nets became the main mode of operation for the Royal Navy until October 1916, when bad weather dispersed the blocking force. In the spring of the following year, 1917, the blockade operations resumed.

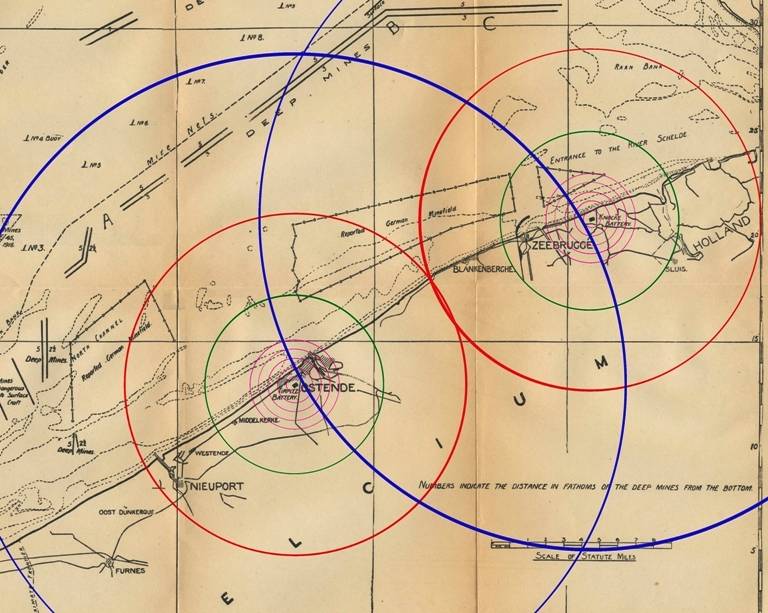

German defense

The main batteries covering Zeebrugge through Ostend included the Tirpitz battery, which was equipped with modern 280 mm (11-inch) guns with an estimated range of 18 miles. The battery was located in Ostend. By 1916, at Knokke, just up the coast from Zeebrugge, the Germans had also stationed a new battery, known as the "Kaiser Wilhelm II" battery. The battery was armed with four 305-mm (12-inch) guns. Other batteries included 150 mm (6 in) naval guns installed at Raverside and some old 280 mm (11 in) naval guns in the Hindenburg battery, centered east of Ostend harbor. In total, by the beginning of 1917, about 80 guns of 150 mm caliber and above were placed on the narrow Belgian coast.

These batteries posed a serious threat to any ships approaching them, which meant that any frontal attack by a relatively slow landing force could end in disaster before the landing force even reached the harbor. The approaches to harbors and coastal shores were increasingly mined by the Germans, which made the task of blockade difficult and dangerous. But, more importantly, it created a serious obstacle to the landing. The relocation of the attack site could reduce the direct threat from the German artillery batteries, although the landing force would still potentially be within range of the Tirpitz battery or other coastal defenses. For example, the 305-mm guns of the "Kaiser Wilhelm" battery could fire on blocking ships at a distance of at least 17 miles (27,4 km).

The area along the coast behind the trenches of the front line at Nieuport was defended by the German 1st Marine Corps Flandern, consisting of the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions. To the south of them was the 199th Infantry Division, covering positions across the Yser River. The two Marine divisions were later reinforced by a third Marine division in July 1917, and there were also reserves from the 4th Army. Along the coast there were about 33 concrete positions for machine guns, one for every kilometer. In addition to all this, after June 1917, the Pommern battery was built 3 km north of the city of Kukelare. Although the battery was no more than 10 km south of the coast, the battery used the 38-centimeter (15-inch) Lange Max (Big Max) gun, at the time the largest gun in the world, with a range of over 38 km and an explosive projectile containing 62 kg of explosive.

It is important to note that the attack along the Belgian coast, at first glance, could take the Germans by surprise, but this is not the case. In fact, Admiral Schroeder, commander of the German naval corps, also saw what Admiral Bacon saw, although some time after Admiral Bacon.

In June 1917, he issued a memorandum to his divisional commanders on precisely this occasion, even indicating the best location. A memorandum which was then canceled in October 1917 due to Admiral Schroeder simply changing his mind. Instead of landing at Westend, he decided that the British would launch a direct attack on the harbors of Ostend or Zeebrugge from land, the exact opposite of how the British actually planned the attack.

wrote Admiral Schroeder in June 1917.

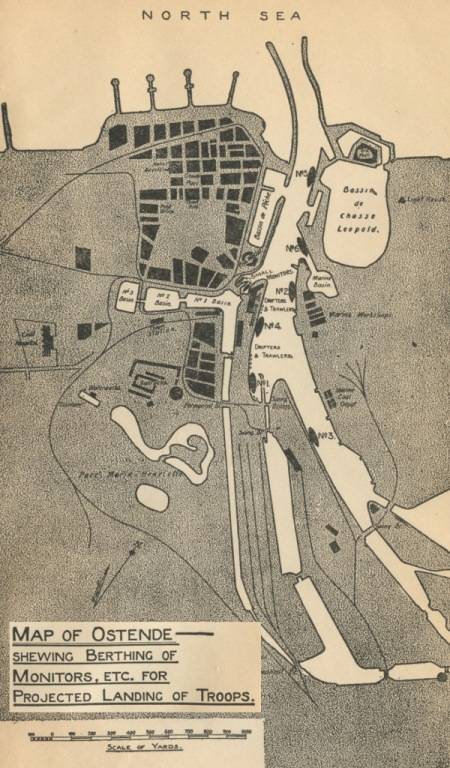

Plan for Ostend

The plan for an amphibious landing on the Belgian coast was discussed by Admiral Bacon at the end of 1915 with the main goal of stopping the German minelayers operating from the coast. He was well aware of the impact this could have on the neighboring country of the Netherlands (a neutral country), which would have to understand its own vulnerability of its coastal cities. How this might have affected the war was not clear, but the possibility of the Dutch entering the war was unthinkable.

Studying the vulnerability of the German flank on the Belgian coast and defenses, Admiral Bacon estimated that the area might be vulnerable to a surprise attack from the sea. Attack at dawn and surprise will be the biggest advantage. Only in this way will the ships break into the harbor of Ostend. Having reached the coast by ships, the soldiers could land with the support of the fire provided by the monitors.

This plan relied on the rapid deployment of troops to overwhelm the defenses and storm the batteries before they were targeted by the Germans.

Still, landing on the pier turned out to be more difficult than expected, as Admiral Bacon worked out all the details.

- Sir Bacon wrote in his memoirs "The Dover Patrol 1915-1917".

Fire support was to be provided by 6 monitors. Each of these ships will carry a pair of 12-inch and two 12-pounder guns, 2 Maxim machine guns, and other light weapons that may be required to suppress the enemy. Each of these would also carry up to 300 men who could be thrown into the shallow water and support the attack.

Several other monitors carrying one 9,2-inch and 12-pounder each and a pair of Maxim machine guns will support these 6 assault monitors.

It was understood that, since the fighting phase in the city would be the most difficult, as buildings would have to be cleared, the main support that could be provided would be localized small arms fire and artillery bombardment of the outskirts of the city, mainly to the west of the city - the expected direction of approach German reinforcements.

Once the wharfs were secure, six close support ships would dock and deliver a cargo of field guns and armored vehicles to support the assault on the artillery batteries and widen the gap in the German defenses. The timeline for success was a narrow gap of only 48 hours from assault to capture of positions in preparation for the next attack on the coast.

Fire support

Fire support was planned to be provided by artillery systems of various calibers. Among them was the only 12-inch (305 mm) Mark X gun weighing 50 tons on a 50-ton mount, which was delivered by the British Navy to Dunkirk. The Mark X was eventually installed 16 miles from the Tirpitz battery.

It was then joined by three 9,2-inch (233 mm) guns weighing 30,5 tons each and eight 7,5-inch (190 mm) guns. They were to be followed by 3 experimental 18-inch (455 mm) guns, each weighing 152,4 tons, and special mounts that could be based at Westend, just down the coast from the landing site and on the British side of the front line. These huge guns, capable of firing through German positions, could support troops moving inland.

But this plan had to be abandoned due to the lack of available places on the coast to install guns.

The purpose of this heavy artillery was to bombard the Tirpitz battery to make it easier to occupy, and then provide ground fire support for a successful landing. Although this landing never took place, these guns still had to do a lot of work a little later, bombarding both the Tirpitz battery and other German positions.

French troops also did not stand aside. They provided two monitors, albeit ancient ships, at least in operational condition. In addition to the ships already provided, two 9,2-inch railway guns were also brought in, capable of firing at German positions in support of the British 12-inch guns.

The effectiveness of the artillery support plan proposed by Admiral Bacon was tested on July 8, 1916, when French railguns opened fire on the Tirpitz battery. The British 12-inch guns also fired 21 rounds at the battery. The counter-battery response from the Germans was ineffective. 104 shells were fired at the French guns, but only a few hit the target. True, it was an abandoned British artillery position on the sand dunes.

However, the rail-mounted French guns were more vulnerable than the British positions, and the French command withdrew this valuable weapon.

To mask British gunfire and avoid German counter-battery fire, Admiral Bacon devised a ruse by which HMS Lord Clive, one of his monitors, fired blanks while his ground guns fired live rounds. Thus, the Germans will be led to believe that they are being fired upon by Lord Clive.

This ended the second day of the artillery bombardment of the Tirpitz battery, after which the British 12-inch guns were worn out and needed to be re-equipped. Battery damage was minor. But still, four firing points were hit, and two were temporarily disabled.

Thus, the artillery plan was considered reasonable, capable of helping to occupy the Tirpitz battery and thereby allow the landing force to land without serious interference from the enemy.

Of course, it was a bold plan, but also a very dangerous one. The narrow entrance and the length of the channel through which the unarmoured trawlers had to pass before they could disembark the troops left their men on board perilously exposed. And they had few alternatives if things went wrong. If one ship caught fire or was temporarily disabled, it could block the channel long enough to trap part of the assault force and make it easy prey for the German forces.

With the installation in February 1916 of the Kaiser Wilhelm battery (called the Knokke battery by the British) with modern 12-inch guns, the Germans would be able to bombard the harbor of Ostend. And that will be a huge problem. As Bacon later wrote:

Plan 2 - Middelkerke option

The Belgian landing plan was originally focused on a direct attack on Ostend itself, but this was abandoned after stormy weather in late 1916 and the establishment of the Kaiser Wilhelm battery.

The landing could not be moved north along the Belgian coast, as it was still within range of the Kaiser Wilhelm battery and, furthermore, there was a border with neutral Holland. The obvious solution was to move the landing force south, out of range of these guns, and also closer to supporting the British forces.

Admiral Bacon was visibly disappointed that his bold plan to take Ostend by amphibious assault was rejected, but this was not really a surprise given the risk involved. However, he did not give up. Soon Admiral Bacon would meet the best experts on every topic of attack available, including Sir Henry Rawlinson. Together, in the unity of the thoughts of the army and navy, they will begin work on a new plan. As the new plan developed, they had the newest weapon in the British arsenal available for 1917 - the tank.

The coast to the west of Ostend was a tempting target, but there was a problem. It was protected from sea erosion by a large concrete seawall 30 feet (9,1 m) high and sloping at a 30 degree angle with a buttress at the top 3 feet (0,91 m) high.

On this subject, Bacon wrote:

With such a narrow coastal zone, this prospect, however unpleasant, was the only way out, so a solution had to be found to the problem of this daunting obstacle.

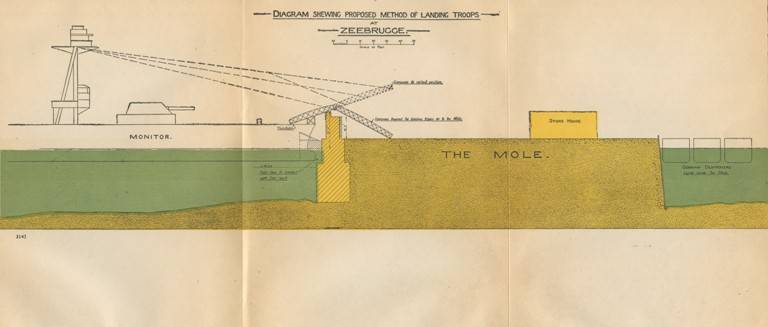

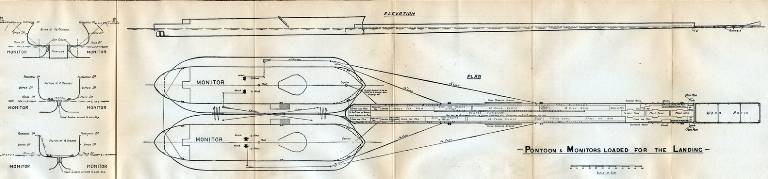

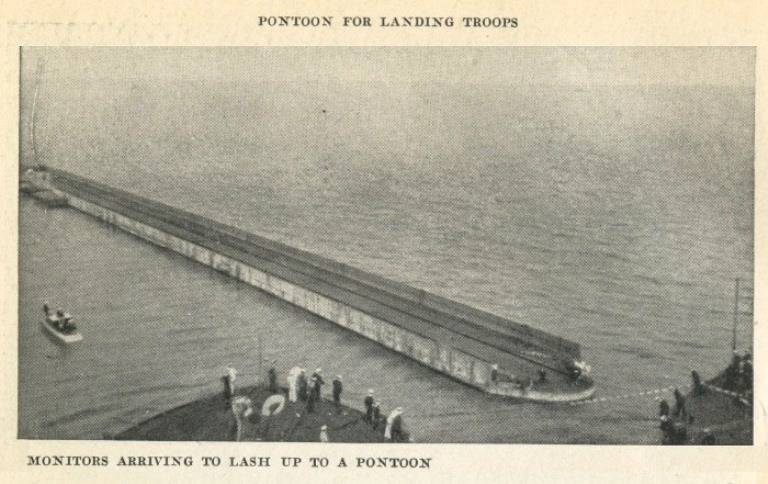

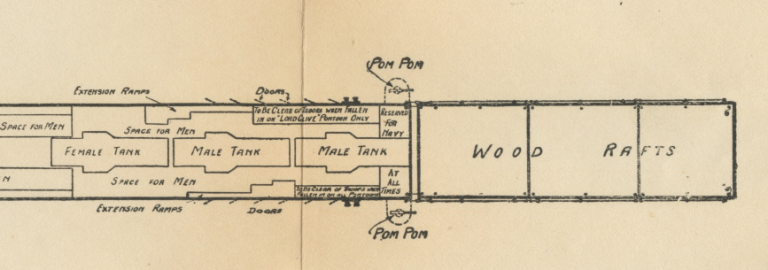

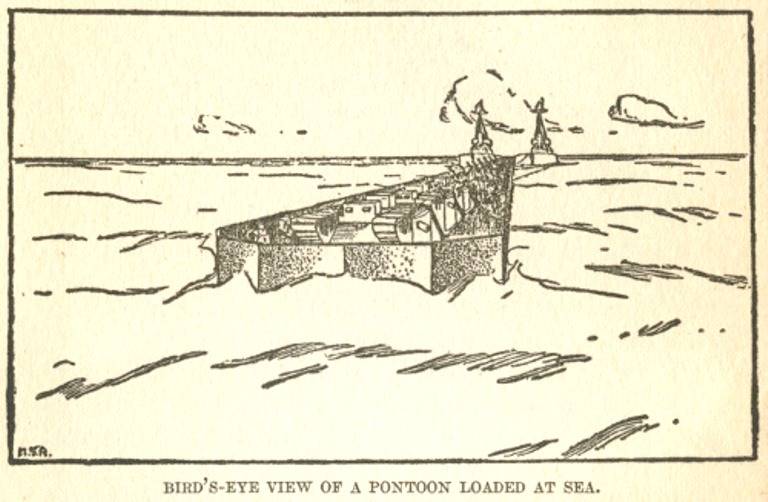

Under this new plan, troops will not be offloaded from clumsy trawlers, nor are vehicles to be unloaded on the wharf. Instead of taking over the car unloading dock, Admiral Bacon designed a portable wharf that the assault forces would bring with them. Formed as two giant pylons or pontoons, each weighing about 2 tons, 400 yards (200 m) long and 183 feet (30 m) wide, they will push ahead of a pair of monitors linked together. The latter, in turn, would also provide fire support. The sides of this pier were made of strong wooden walls, and in front, in the part of the raft, there were supports of 9,1 foot (1 cm) timber with iron supports 30 square meters. feet (4 sqm) to provide traction.

The attack itself was supposed to take place under the cover of a smoke screen, which was provided by about 80 small ships. On each ship there was about 630 kg of phosphorus, from the combustion of which a smoke screen was exhibited.

However, this plan to push through the pier was not the intention of Admiral Bacon. The idea was first proposed by Sir Henry Jackson (then First Sea Lord) in the autumn of 1916, but Admiral Bacon took the idea in a new direction. Positioned in front of the monitors, these piers, equipped with their own guns and laden with men and tanks, would be moved ashore and vomit their contents onto the waiting and outnumbered German defenses. There, the monitors could remain attached to the pontoon despite a large tidal range of about 8,5 feet (2,6 m). This meant that the piers had to be very long to keep the monitors, with a draft of about 9 feet (2,7 m), from falling on the sand as the tide went out.

At the very front of the assault pier or "pontoon" was a row of flexible wooden rafts 150 feet (45,7 m) long, made from two layers of 4 inches (102 mm) thick timber, which could move to compensate for any bending of the pier when moored and unloading.

The speed of this megalithic structure on the water was low - only 6 knots (11,1 km / h), and the landing had to take place as close to high tide as possible, so the time was carefully thought out. Had they placed the buttresses in the right place, the buttresses, each 200 yards (183 m) long, would have extended over much of the long, gentle slope to the sea in the Middelkirk area. The distance from low tide to the sea wall was only 275 yards (251 m), so that only 75 yards (69 m) of open beach had to be traveled to storm.

When planning the operation, a possible date was assumed: the beginning of July 1917.

One pontoon was built and tested at the mouth of the river. Swin near Essex in March 1917 The pontoon-monitor scheme was a guaranteed success. Therefore, two more pontoons were immediately put into production at the Chatham shipyard.

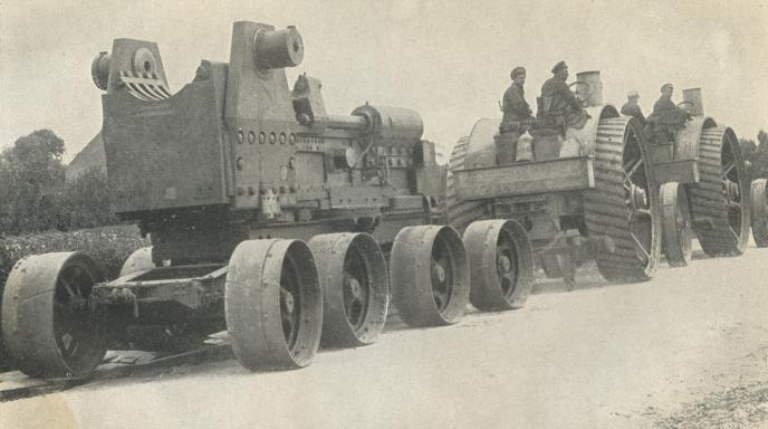

Tanks

Tanks were new in the sense that no one had any experience in amphibious operations with tanks of any type from which to draw inspiration.

Tanks were, of course, of great importance for the offensive. But, firstly, can they be carried on a pontoon? And, secondly, could they climb the wall?

To the first question, the pontoon designer Lillikrap answered in the affirmative, with some reservations about their position.

Regarding the second problem, Admiral Bacon also had no doubts. And everyone got down to business.

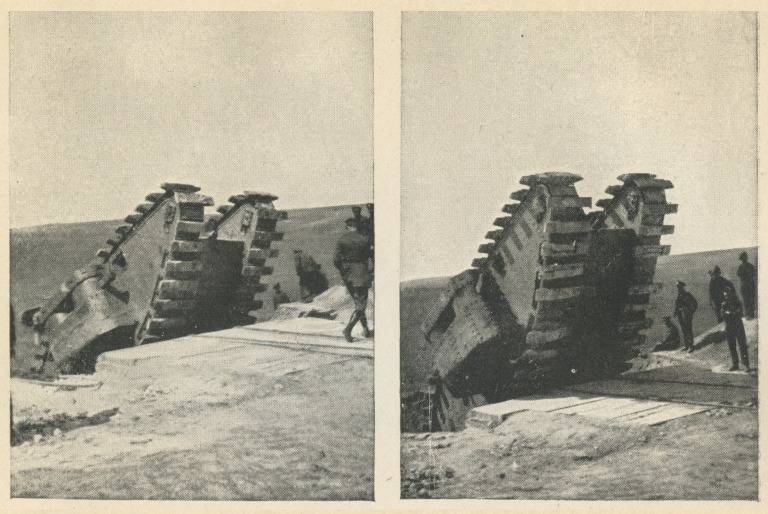

The slope of the wall was 30 °, and when the tank approached the ledge, the front part of the caterpillar had to rest against it with almost linear contact. Further movement will raise the entire tank and reduce the area of that section of the rear of the caterpillar that is in contact with the sloping wall, which will negatively affect further advancement.

In addition, the greatest angle that a tank with its more or less limited power could climb was 45°. Overcoming the wall with an armored vehicle will mean that the rise of its center of gravity will be an angle of 60 °. To ensure that the angle of inclination did not exceed 45° when lifting up, the vertical height of the ledge above the sloping wall had to be removed. And for this, the rise must begin at least twelve feet (3,6 m) from the base of the ledge.

If a tank could not be forced to climb a wall, it was useless, so a solution was needed.

And he was soon found - this is the creation of an inclined path for carrying and placing the tank itself so that it can climb the fence. The top surface of the ramp must not slope more than 10° to the slope of the wall.

A replica of the sea wall at Middelkerk was created from concrete at Merlimont in France in April 1917. It is worth noting that one of its former architects, who was tracked down in France as a refugee, helped to build the model of the wall, and who, as it turned out, had the original plan of the wall.

Here is what Sir Bacon writes about the trials on the wall in his memoirs:

This improvement was sloping ramps. According to Admiral Bacon, the large sloping ramps, thick enough to carry the weight of the tank, were made in Britain and sent for testing.

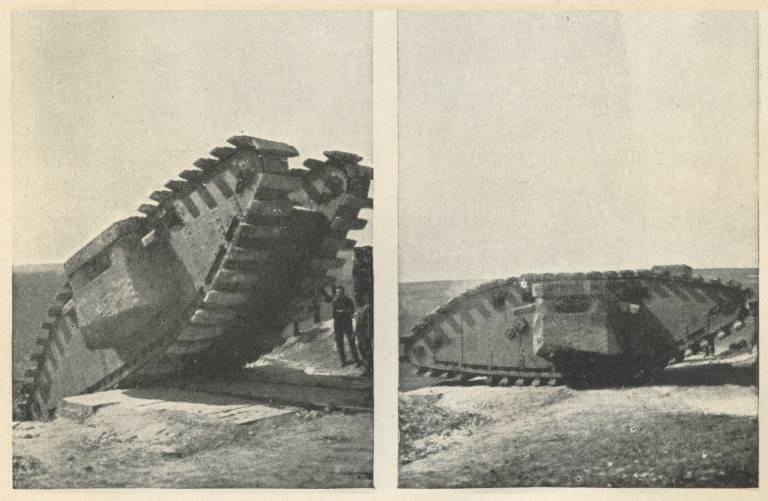

On June 9, more satisfactory tests were carried out. Carrying this ramp, the tank approached the wall until the ramp touched it. Then the ramp, supported by a pair of wheels, moved up the slope like a wheelbarrow ahead of the tank until it hit the protruding upper edge of the wall. The sharp protrusions of the ramp stuck into the wall so that the ramp was securely fastened and could be detached from the tank.

On inclined ramps, transverse wooden planks were strengthened. When the tanks climbed the ramp, its caterpillars engaged with these bars and thus the tank climbed the wall like a ladder.

This method proved to be more acceptable. After this test, all equipment was transferred to the tank corps for its improvement.

At the same time, troops of the 1st Division of the 4th Army, specially selected by General Rawlinson to deliver the pier, began landing training. To ensure the secrecy of the preparation, the troops were assembled in an isolated camp at Le Clipon, near Nieuport.

After some practice, these troops were soon able to land from the artificial assault pier in just 10 minutes, half as long as Admiral Bacon allowed. They could also easily climb a wall in full kit, although the tanks would have to haul or lift guns, wagons, and other heavy items up a ramp.

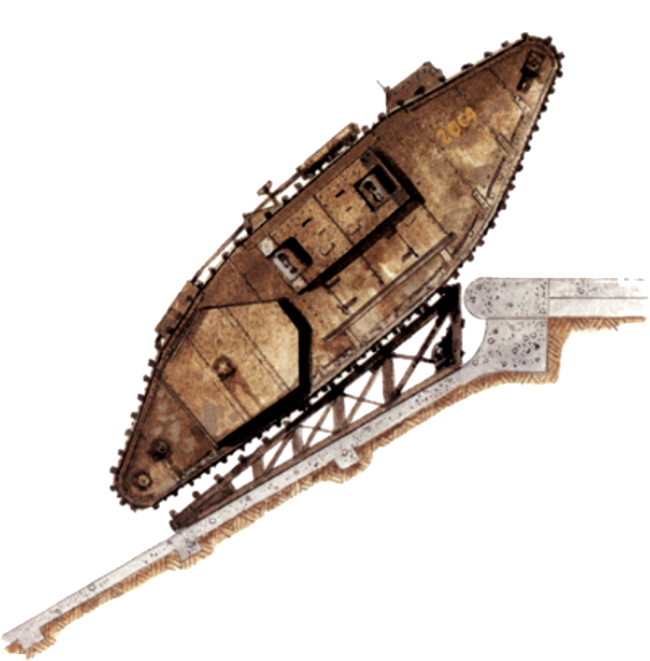

To this end, a special type of cable winch was developed for Operation Silence. The winch was on the right side of the tank and was powered by a secondary gear extension that extended beyond the original side armor.

In the photo below, Mark IV Male 29064 shows the location of the new side armor panel in the rear, covering the cable winch. A winch was not added to the left side of the tank, there was simply no need for it. This single side extension was enough to haul guns, carts, wagons, and wheeled vehicles across the sea wall.

It may also have been suggested that this be used as a means of helping a broken tank. We do not know the exact capacity of the winch or cable, but it would be sufficient, at least for heavy guns and wheeled vehicles. But it is quite another matter to tow a tank.

The plan for the assault at Middelkerk (picture below) was to land nine tanks on the coast in a three-pronged attack (red arrows) on the edge of the German front. The troops must then advance inland (dark red) to secure a foothold and destroy the German guns. This attack would have been supported by British forces advancing from Newport (yellow) and advancing towards Westend (orange). Together with the air assault group, they would support the advance inland (green).

Атака

The actual attack was to take place in the same time frame as the Ostend plan (July-August). The attack was to take place at dawn, with the tide as high as possible. Such requirements limited the time to 8 days in any particular month. This would also ensure that neither tanks nor men would have to navigate water deeper than 3 feet (0,91 m), which was fortunate since the tanks were not waterproofed and in deeper water they would be flooded through the side doors.

The best day to attack was 8 August 1917, as not only were the times and tides correct, but there was no moon to illuminate the attacking forces for the German defenders. But General Rawlinson soon learned that the intended attack on Ypres, scheduled for 25 July, had been postponed to 31 July. This meant shifting the landing date from 8 August to either 24 August or 6 September so that landing conditions would again be ideal.

But on August 22, I had to be very disappointed. Despite General Du Camp's (XV Corps) request that an amphibious assault precede his attack as a convenient diversion for the Germans, Field Marshal Haig, the commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force in France, delayed the operation to an unspecified date after 6 September. However, a new date has not yet been set.

Soon at Headquarters

Sir Bacon wrote later in his book.

An alternative was proposed at the beginning of July 1917 as a more modest option. This plan, proposed by Admiral Bacon, was simply to storm the shore batteries of about 100 guns of various calibers in the area by storm and then capture and hold Westende. This breakthrough would have created a significant gap in the northern part of the German defenses, allowing any German position between Nieuport and Westende to be bombarded and then attacked from both directions - an unpleasant thought for the Germans, who would be trapped between these two fronts. This would also allow the fleet to land guns at Middelkerk with a range of fire over the harbors of Ostend and Zeebrugge and the docks at Bruges. But, as mentioned above, this option was rejected.

Conclusion

The exact date of the landing as part of Operation Silence has not been set. Sir Douglas Haig insisted that the main attack should reach Rulers, five miles from Passchendaele, before an amphibious attack could be mounted, but the attack never got that far.

The expected results of the Third Battle of Ypres never materialized. Flandern's Marine Corps found that the British had captured the Yser beachhead and launched a preemptive attack (Operation Strandfest), depriving the British of their foothold to support the attack along the coast. Operation Hush ("Silence") was canceled and the landing never took place.

And although the landing party was kept incommunicado for some time in the Swin Strait, it was eventually disbanded.

On July 6, 1917, Flandern's Marine Corps began an indiscriminate artillery barrage that continued for the next three days. Fog and low overcast prevented the German build-up from being detected. Then, at 5:30 am on 10 July, German artillery, including three 24 cm naval guns in shore batteries and 58 artillery batteries (scheduled artillery support for ship destroyers and torpedo boats was cancelled), opened fire on British positions in the east of the bridgehead. All but one of the bridges over the Iser River were demolished, isolating the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division on the extreme left flank.

Telephone communication was also interrupted. The German bombardment continued throughout the day. The British artillery tried to counter-attack, but several guns were disabled and the German infantry was heavily defended. At 20:00, the German Marine Corps launched an attack. By this time, the losses of two British battalions amounted to 70-80%.

German attack aircraft attacked the coast, outflanking the British. Their attack was then followed by waves of German marines, supported by flamethrowers, who cleared the dugouts. After a long defense, the British battalions were defeated. Only 4 officers and 64 privates managed to reach the western bank of the Isère.

The Battle of Passchendaele was a bloodbath, there was no breakthrough. Soon the 1st division was urgently transferred to the south. The failure of the army to secure this breakthrough meant that plans to land on the Belgian coast were not to be realized.

All the lessons that the Dover Patrol learned and worked through in 1916-1917 had to be rethought and reworked a generation later.

During the Second World War, the British will still be able to complete one of the largest amphibious operations with the landing of tanks on the coastal strip occupied by the enemy.

It will happen in June 1944 in Normandy.

Information