Siege of Beirut by Captain Kozhukhov

By that period, the internal political situation in Rzecz Pospolita once again became aggravated. There was a unique event for the century absolutist monarchies - the election of the king. In addition to direct candidates, those countries that influenced such a difficult situation were directly or indirectly involved in the pre-election race. Of course, the influence was feasible: gold, intrigues of diplomats, well, and regimental columns gathering dust off-road, of course.

Thanks to the clear and accurate position set forth by Russia, expressed not only in the introduction of army contingents into the territory of a neighbor, the deployment of garrisons in all major cities, but also a whole complex of other measures, Poniatowski was elected Polish king. The reforms initiated by this monarch (and especially the equalization of the rights of Catholics with representatives of other denominations) caused the outright fury of a part of the clergy and nobility. Protest events soon took shape in the creation of a Confederation in the city of Bar in order to counter the king and the Sejm.

The opposition was very determined, the benefit of its ranks were not retired chess grandmasters or street musicians, who were defeated by the big stages, and began to arm themselves. “March of Dissent” of the convocation of 1764 from the first weeks began to resemble an internecine war. Struggling against the king, the Sejm and the invaders from a famous country, the Confederates did not forget to give attention to the Orthodox population and the clergy living in the territory of the Commonwealth. This attention was mainly expressed in interfaith dialogue, which took place in the form of mass executions, reprisals and robberies.

The answer was a popular uprising, known in stories as koliivschina. The patriots and the “fighters against the regime” have succeeded so much in their zeal that they have, without much difficulty, turned a large part of their own population against themselves. During the uprising, an incident occurred near the city of Balta, a border settlement, located on the territory of the Ottoman Empire. The detachment of the rebels, pursuing the enemy, in the excitement invaded Turkish territory. The case had all chances to be deflated, but from the high towers of Istanbul in what was happening they considered a completely different meaning and depth. The blessing at their base were exquisite gentlemen in wigs and kindly prompted upstairs what, how and where to shout. The wigs and uniforms of these advisors were fragrant with the exquisite aromas of Versailles fashion.

As a result, the Russian ambassador to Istanbul, Alexei Mikhailovich Obreskov, was sent to the Seven Turreted Castle while trying to talk with the Grand Vizier who had called him. It was September 1768 of the year.

Archipelago Expedition

Unlike the Ottoman Empire, whose leadership, nostalgic for the times of Mehmed II the Conqueror, decided to smooth out several banners that had already been adopted, Russia did not want a war. Catherine did not feel completely independent, because a flock of Orlov brothers still circled around the throne, whose support she could not ignore. The Polish crisis and related international problems also took a lot of resources.

A different opinion prevailed in the respective offices of France. The solid foundations of this country’s Middle Eastern policy were laid under Cardinal Richelieu and Minister Colbert. The Ottoman Empire began to occupy an increasing place in the French plans. The external economic turnover between the two countries was steadily growing - Marseille trading houses found extensive markets in Turkey and, in turn, could buy and then resell Eastern goods in Europe at very favorable prices. Any infringement of Turkey somehow hit the French economy.

In addition, Versailles had its own interests in Poland. With the formation of the Bar Confederation, General Dumouriez was sent there with a group of officers, in abundance supplied with money and weapons for the rebels. Nor did French diplomacy rest in Istanbul. The strategy of Versailles was as follows: to tie Russia’s hands in Poland, incite the Omanian empire against it, while exerting pressure from Sweden. Fully entangled in solving problems with its immediate neighbors, Russia, according to French diplomats, will disappear from the horizon of European politics for a long time.

However, France’s main historical rival, the island nation on the other side of the Channel, had its own vision of the Middle East situation. England in continental affairs sought a strategy of equilibrium, and she was not satisfied with the excessive weakening of Russia in the Turkish direction. Petersburg for the time being was for her evil far less than that filled with revanchist intentions after the lost Seven Years War France.

In the intricacies of the corridors of British foreign policy, the project of the “northern union” was soon born, the ideologist and centripetal force of which was William Pitt the Elder, the first Count of Chatham. According to this plan, it was necessary to create a bloc from England, Russia and Prussia for coordinated counteraction against the French and Spanish Bourbons. Ideally, this “northern union” was supposed to lead to a European war, where the hands of Russians and Prussians would completely rid the Versailles of any serious political ambitions. The main work would lie on the bayonets of the continental allies, whom London would occasionally throw up gold while doing its own business in the colonies.

In general, everything was fine, it remains only to persuade the empress. But with this, serious difficulties arose, since Catherine II was a little like an enthusiastic lady who collects clothes and jewels (although she was not alien to such entertainments).

English diplomacy began to probe the soil already in the middle of the 60s. XVIII century, and the first attempts were successful. In Petersburg, they reacted to the efforts of London with polite attention. However, to give any guarantees and incur obligations Catherine II, with her inherent grace, smoothly refused. Such a strategy has borne fruit - by the time the war with Turkey began, England took a position of friendly neutrality towards Russia.

In Petersburg, they were going to fight the Ottoman Empire not only by the forces of the ground army alone, but by other available means, such as the fleet and the Greek insurgents. It is believed that one of the first to make a proposal to send a squadron from the Baltic to the Mediterranean Sea for “sabotage” was Count Alexei Orlov, Grigory Orlov's younger brother.

Alexey could not only amaze guests at balls and receptions with glaring ignorance of etiquette and rude manners, but was also capable of generating useful ideas and ideas. Not receiving sufficient education, not fluent in foreign languages and not aware of the intricacies of philosophy, Orlov nevertheless was not at all so simple. The graph was by nature a man of inquisitiveness, many were interested and patronized by the sciences. His idea of a “sabotage” squadron was also supported by his elder brother, Grigory Orlov. In the conditions of the outbreak of war, when plans for conducting it were thought out literally on the knee, the thought of Alexei Orlov had every chance of success.

Preparations for dispatch began in the winter of 1768 – 1769. Since the Baltic Fleet was at that time in a rather neglected state, the formation of the expedition took place with a distinct creak. There were problems not only with the technical condition of the ships, but also with the completion of the latter by personnel. However, most problems were either overcome or bypassed.

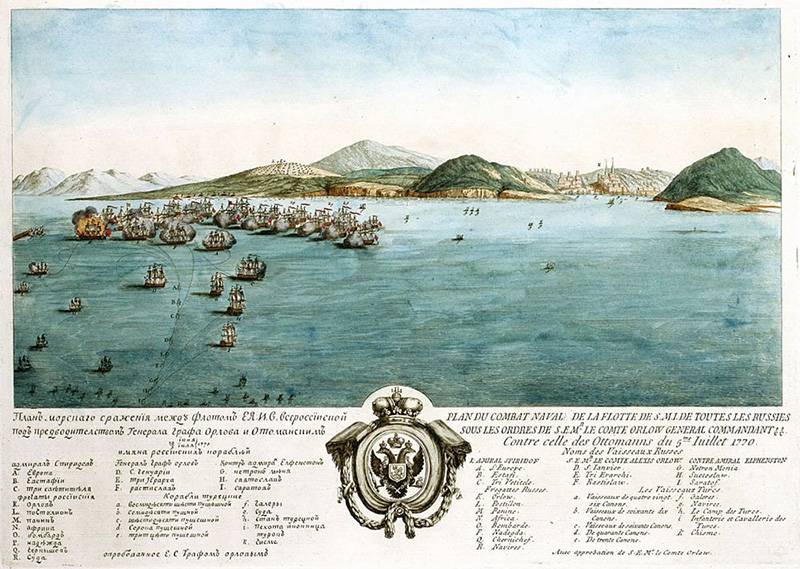

In July 1769, Kronstadt left the squadron, consisting of seven battleships, one frigate, one bombardier ship, and four files. Its armament was six hundred and forty guns, on board were five and a half thousand personnel, including sailors, soldiers of the Kexholm regiment, artillerymen, sappers and artisans. General leadership was entrusted to Admiral Grigory Andreyevich Spiridov.

Later on, it was planned to send other squadrons to the Archipelago as soon as it was ready. The general leadership of all the expeditionary forces in the Mediterranean basin was entrusted to Count Alexei Orlov, who was to arrive at the scene by land. Campaign Spiridov squadron was accompanied by all sorts of difficulties. Already on the way to England there were more than seven hundred patients on board because of poor-quality provisions and poor sanitary conditions, and the ships themselves were pretty battered by storms. Still, the Russian sailors then lacked the experience of long transitions as part of large units.

In the formally benevolently-minded England, Spiridov was assisted - repairs and restocking. English officers and sailors were taken to the Russian service. In December, the 1769 of the year, the Russian squadron began to concentrate on planning in Port Magon on Menorca. Part of the ships lagged along the way, and they had to wait. The transition from the Baltic turned out to be a difficult test: during it about four hundred personnel died from diseases.

By the way, Spiridov’s campaign was widely reported in the European press of that time. Newspapers, especially French ones, frankly ridiculed Russian sailors, finding this whole undertaking of the senseless stupidity of the Eastern barbarians. The naval circles of France were generally filled with malicious skepticism.

In January 1770, the finally assembled Russian squadron left Port Magon. Count Aleksey Orlov, who arrived at the scene, came aboard in Livorno and immediately made it clear to Spiridov, whose plume on the hat is more magnificent. The commander was full of zeal to implement his military plan, in which the fleet the modest role of the carrier of the troops was given. The main bet was placed on the Greeks of Morea, who, according to Orlov, were only waiting to massively revolt against the Turks and stand under Russian banners.

There were indeed many armed Greeks, but not enough to form a large army in a short time. Overwhelmingly, these were dashing people who were engaged in robbery and piracy. Their individual fighting qualities were beyond doubt, but the Greek rebels had nothing to do with the concept of discipline and organization. In fact, these were armed gangs, and it was no easier to give them a more outlined form than to form a Spanish third from the liberty of Tortuga Island.

Subsequently, Count Orlov often complained about the Greeks: ostensibly because of their lack of organization and lack of discipline, they failed to create a strong springboard in Greece. In fact, the series of tactical amphibious operations conducted in the spring of 1770 with the widest involvement of the Greek contingent eventually turned into a failure at the fortress of Modon, near Navarin. As a result, having suffered heavy losses and having lost all the artillery at the same time, the landing force was forced to retreat to Navarin and evacuate to the ships.

Orlov too overestimated the strength and capabilities of the Greek rebels. Even before the war, arriving in Italy for "treatment", the count was engaged in intelligence activities and had numerous contacts with representatives of Greece, Albania, Serbia and Montenegro. They, not sparing paints, painted how the Balkan boilers boil, how couples swirl in them in an unprecedented intensity of explosive mixture waiting for its spark. At the same time, emissaries did not forget to modestly ask for money "for firewood."

Of course, the situation in the Balkans and in Greece was very complex and permanently smoldering, however, from the information received, Aleksey Orlov drew somewhat hasty and too optimistic conclusions. In any case, as it turned out in practice, the freedom of their own trade to the Greeks was much more interesting than the abstract dreams of the revival of Byzantium.

Not having achieved the desired result in the landing operation, Orlov, not without the help of Admiral Spiridov, came to a quite sensible decision: to find and destroy the Turkish fleet in order to carry out the blockade of the Dardanelles in the future. Especially since the Russian grouping in the Mediterranean was reinforced by the arrival of reinforcements - the squadron of Admiral Elphinstone. The Turkish fleet failed as a result of the Battle of Chios, and then was destroyed at Chesme.

Having seized domination in the eastern Mediterranean, the Russian command proceeded to perform the following task - the blockade of the enemy capital. In France, they reacted to the successes of Russia with distinct signs of migraine. More recently, the decorative fleet of Russian barbarians cleaned by newspapers and court wits destroyed a significant part of the Ottoman Empire’s naval forces. But part of the Turkish ships was built according to French designs and with the help of French engineers.

The situation seemed so harsh that the naval minister, Count Choiseul, was seriously considering the option of a surprise attack on Orlov’s squadron. In fairness it should be noted that Versailles’s intrigues in maritime affairs began at the stage of Spiridov’s transition from the Baltic. “Merchant” ships under the French flag, whose actions could be regarded as espionage, often went out to meet the Russian squadron. They behaved arrogantly and boldly. The calculation was that the Russians, having lost patience, would arrest the “merchants”, and this incident could be used as a pretext for an international scandal under the slogan “savages invade peaceful merchants”.

However, the Russian sailors did not succumb to the provocation attempts - Spiridov was an old and experienced handmaid. However, soon the French migraine was somewhat reassured by the application of English ice. On the island, it was believed that Russia would bring more benefits if it was not burdened with a weight in the form of a war with Turkey, and for the big game it would be necessary to end it. French anxiety, though carried away Petersburg to the “right” channel of confrontation with Paris, which, however, was considered by gentlemen to be premature and extremely undesirable. In addition, living the last years of his loving life, Louis XV had no interest in what was going on outside the Gate of the Stag Castle.

After confident victories, the Russian fleet quite firmly blocked the approaches to the Ottoman capital, where serious food supply disruptions soon began. The land company also developed quite favorably, and in such circumstances the enterprising Englishmen offered mediation efforts in the matter of making peace. However, the Turks were not ready to recognize the existing reality as obvious, and the war continued.

It should be noted that the squadron Spiridov was engaged not only in the blockade of the Black Sea straits, its ships carried out operations in other regions. First of all it was Greece and the islands of the Archipelago. Part of the Greek rebels filled up the crews and landing parties. In the spring of 1773, when the outcome of the war was no longer in doubt, a detachment of ships with troops was sent to the shores of Syria. He was commanded by the captain of the 2 rank, Mikhail Gavrilovich Kozhukhov, a person on the Archipelago expedition is far from accidental and caught the eye of the authorities long before the events described.

Man from the hinterland

The place and time of the birth of Mikhail Kozhukhov remained unknown. His last name is mentioned in the documentation for the first time in 1758. This year Kozhuhov was assigned to navigational students - because of the "failure to prove" noble origin. In the maritime order of the Russian Empire at that time, the rank of ship navigator was equated with non-commissioned officers. Often such people were greeted with coolness in the officer corps, consisting of nobles. The navigator could only go into the caste of naval officers of the army officers only during the war, making a deserving attention, in other words, a feat. Or he should have outstanding personal qualities and abilities.

It seemed that Kozhukhov was destined to serve his entire life as a navigator, but circumstances, like the direction of the wind, are very changeable. A navigational student who was capable of science was lucky - on one of the exams he was noticed by Admiral Ivan Lukyanovich Talyzin, an old warrior who began his career in Petrine times. His troublesome young man transferred to the Cadet Corps. Already in April, Mikhail Kozhukhov’s 1759 was fired as a midshipman and enlisted in the fleet.

Russia entered the Seven Years' War, and the young man had a direct opportunity to put their knowledge and skills into practice. The next few years passed in the military strand - in 1761, Kozhukhov was given the title of midshipman. He distinguished himself during the capture of the Prussian fortress of Kolberg.

The course of the war has changed in unexpected ways. The new monarch Peter III, who replaced Elizabeth Petrovna, had a completely different view on Russia's participation in the pan-European conflict. With a recent opponent, King Frederick II of Prussia, an armistice was concluded, and then an alliance. These and other events sharply set up military circles, especially the Guard, against the new emperor. The situation was greatly aggravated by the strained relations of Peter III and his wife Catherine, who was a key figure in the preparation of the coup.

The number of denunciations and reports about the grave situation in the guards and the capital did not impress Peter III properly, and in May 1762 he left with his retinue to Oranienbaum. 28 June, the emperor arrived at Peterhof, where they were to go through celebrations on the occasion of his namesake. At this time conspirators began to operate in Petersburg. A part of the guard swore allegiance to Catherine as empress of All-Russia and soon spoke at Peterhof to complete the procedure for the final transfer of power.

Peter III was confused, because the possibilities at which he had to resist were extremely small. On the advice of the old field marshal Burkhard Minich, who was with him, the emperor, however, was very slow, and together with his retinue went to Kronstadt, counting on his garrison and fleet ships. The commandant of Kronstadt Numers was a confidant of Peter III, but the emperor's indecisiveness and, conversely, the quickness of the conspirators allowed the coup to develop in a given direction.

Admiral Talyzin was quickly sent to Kronstadt, taking the side of Catherine. It so happened that at this moment, midshipman Kozhukhov was the head of the guard of the fortress. The first rumors about the events that had already occurred reached here, and Numers ordered not to let anyone off the coast. Admiral Talyzin, however, was well known to the midshipman, and he easily let the boat on which he arrived. The old servant quickly changed the situation in the fortress, taking into custody all supporters of Peter III. The emperor, meanwhile, decided on a court yacht and headed for Kronstadt. The yacht was accompanied by the galley on which the retinue was located. When approaching the fortress, it became clear that the entrance to the raid was blocked by a boom. It was put up by order of midshipman Kozhukhov. An attempt by Peter III to disembark from the boat was decisively intercepted by the commander of the guard. The persuasions and threats of the emperor had no effect, and he was forced to return to Peterhof.

The decisive and clear position taken by the midshipman Mikhail Kozhukhov was subsequently marked at the very top. His actions were described in detail by Talyzin in the report already in the new highest name. Soon, in a group with other young officers, he was sent to study in England and, on returning to 1767, after successfully passing the exam, Kozhukhov was promoted to lieutenant commander. He was sent to serve in the battleship "Evstafy", which became part of the Archipelago squadron.

However, a couple of weeks before her departure, Kozhukhova’s career made another sharp turn: by order of the Admiralty Board, he was included on the expedition of Rear Admiral Alexei Senyavin, who was sent to Tavrov to prepare for the reconstruction of the Azov flotilla. Instead of the Mediterranean, exotic for the then Russian man, Kozhukhov found himself in the Black Sea steppes. This fact, quite possibly, helped the captain-lieutenant to save lives, since “Evstafy” was killed in the battle of Chios because of a fire and an explosion of powder cellars.

The grouping of Russian forces in the Mediterranean was constantly growing, and more and more personnel were needed there. A business trip to Tavrov was interrupted in favor of sending Kozhukhov directly to the theater of military operations. He was to join the crew of the battleship Vsevolod.

Already 2 November 1771, Kozhukhov distinguished himself in an operation against the Turkish fortress of Mytilene. Under the protection of her guns was a shipyard, where the construction of two battleships and shebeks was in full swing. The landing force landed ashore ships under construction, destroyed the stockpiled supplies and materials. Spiridov noted the courage of the lieutenant commander and transferred under his command the frigate "Hope".

In the autumn of 1772, the Russian command launched an attack on the Chesma fortress, where the Turks collected large stocks and equipped warehouses. For his bravery, Captain Lieutenant Mikhail Kozhukhov, among others, was awarded the St. George Cross of the 4 degree. The outcome of the war was predetermined, negotiations were held between the two sides, and truces were periodically concluded. The Turks nevertheless used each stage of the dialogue to increase their own defenses, and simply stretched the time. The negotiations that the Brilliant Port conducted with the energy of a camel dealer trying to stick the donkey to the buyer instead of the dromedary were unsuccessful. Important arguments were required, and one of them was in Syria.

Beirut episode

In the spring of 1773, Mr. Mikhail Gavrilovich Kozhukhov, already captain of the 2 rank, commanded a squadron of ships carrying out activities for the blockade of the Dardanelles, along with other detachments. After another successful interception of the transport vessel, which was brought into the fleet operational base at the port of Auza on the island of Paros, he received the order of Admiral Spiridov to go to the shores of Syria. There at that time there were quite large-scale and routine events for the late Ottoman Empire, that is, an uprising.

Back in 1768, the ruler of Egypt, Ali Bey al-Kabir, proclaimed independence from the “imperial center,” reinforcing his actions with armed arguments. In 1770, he proclaimed himself Sultan, and in 1771, he entered into a military alliance with Russia through Admiral Spiridov. Using the support of the Russian command and seeking to expand the territory of those who did not want to "feed Istanbul", Ali Bey moved his activities to Syria, where his troops managed to take Damascus. The struggle for the independence of Egypt was soon overshadowed by a split in the camp of the latter-day Sultan, who was opposed by one of his closest associates.

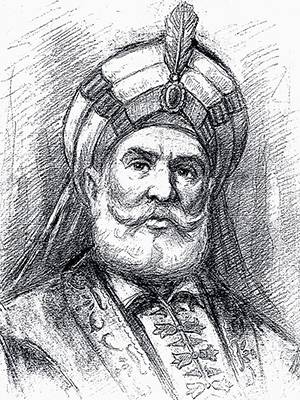

In 1773, after an intense struggle, Ali Bey was defeated in Egypt by his opponents and captured. In Syria, the leadership of the struggle against the Turks passed to Ali Bey’s closest ally, Sheikh Galilee Zahir al-Omar. He was widely supported by the local Druze tribes. The situation in Beirut has escalated - the local ruler, Emir Yusuf Shihab, began to suspect something. An experienced commander Ahmet al-Jezzar, Bosnian in origin, was sent by the Turkish command to Beirut. Jezzar, which means "butcher," was his nickname, which he received for the appropriate attitude towards enemies.

Being located in the city, he began his activities strongly to annoy the emir Yusuf Shihab. Relations in the relationship soon turned into an open confrontation, and the emir who had left his place, after a good thought, turned for help to Count Orlov. The commander, without any hesitation, sent a detachment of Montenegrin Marko Voinovich, a corsair to the Russian service, to Beirut. It included the frigates "Saint Nicholas", "Glory", four semi-galleys and one schooner.

However, these forces were clearly not enough to change the situation with Beirut - the captain of the 2 rank Mikhail Kozhukhov had to tip the scales in the right direction. At his disposal were frigates "Hope", "St. Paul", five Polarok and two semi-galleys. 17 July 1773, both squadrons joined at Akka, and Kozhukhov as the senior in rank (Voinovich was listed as a lieutenant) took command of the operation.

At his disposal was ship artillery and a landing party, consisting not only of Russian sailors, but also of the Greeks and Albanians. The rebels promised help in the form of 5 – 6 thousands of people. Arriving on July 19, Mikhail Kozhukhov entered into negotiations with Yusuf Shihab and the emissaries of Emir Zahir al-Omar. The personal emissary of Count Orlov, Lieutenant of the Guard Karl Maximilian Baumgarten, was present at the squadron. A union agreement was concluded, according to which Beirut will become Russian-controlled territory, but will retain local government.

Yusuf Shihab at the same time said that the Druze will not be able to take part in the operation, since the harvest is now underway, and Kozhukhov will have to rely solely on his strength. We had to abandon the swift assault and begin a long and systematic siege. The first major shelling of ship artillery took place on July 25. Beirut was blocked both from the sea and from land, though not as tight as we wanted. Indeed, the total number of land forces that Kozhukhov had at his disposal did not exceed a thousand people, most of whom were bright representatives of the Mediterranean coastal fraternity.

Four 6-pounders were brought to shore, and two of them were equipped with siege batteries. The shelling did not give the expected effect, since the walls of the fortress were strong, and the emerging breaches were eliminated by the forces of the garrison, which even made forays. There was evidence that the Turkish command was planning to assist the Beirut garrison.

It was necessary to find an extraordinary solution that could change the course of the siege, and it was found. By order of Kozhukhov, the city water supply was discovered and blocked, which soon significantly affected the morale and well-being of the besieged. In Beirut, along with food problems, serious water shortages occurred. The first detachments of the Druze who had resolved their agricultural questions, who strengthened the blockade from the land, began to catch up.

The command of the garrison in the person of Ahmet al-Jezar, clearly understanding the plight of the situation, began to bargain. In order to rid the “butcher” of some diplomatic illusions, Beirut was once again subjected to massive bombardment. This fact has had the most favorable effect on the speed of the Turkish commander’s considerations. His subordinates have already tasted pack animals and dogs, and a dervish arrived as an envoy to Mikhail Kozhukhov, who said that Jezzar was ready to surrender.

30 September 1773, Beirut surrendered. As trophies, the winners got two half galleys, twenty guns, a lot of weapons and other loot. The Turkish command received a contribution in the amount of 300 thousands of piastres, which - to the great joy of the people of Marko Voinovich - were divided between the participants of the expedition.

A separate point of surrender stipulated that the Druze is now under Russian protection. Mikhail Kozhukhov’s squadron soon returned to Paros. True, Beirut was not under Russian control for long - according to the Kyuchuk-Kaynardzhsky peace treaty signed in 1774, it was returned to the Ottoman Empire.

The captain of the 2 rank Mikhail Kozhukhov was awarded the Order of St. George of the 3 degree. The next Russian-Turkish war ended, but big politics continued. Russia will have to send its ships and troops to the Mediterranean Sea, which has firmly become the arena of its interests, more than once. The hero of the Beirut expedition, Mikhail Kozhukhov, retired from the fleet in 1783 in the rank of captain of the general-major rank for health reasons. His fate is unknown.

Information