Pole you can not be. Russian answer to the Polish question. 4 part

Viennese Waltz dancing in Krakow

For the Austro-Hungarian Empire of the Habsburgs, in fact, only half German, the Polish question was not so acute. But in Vienna, they had no illusions in his attitude. Of course, the Habsburgs brought the economic and cultural oppression of the Polish population to a reasonable minimum, but they severely limited all political initiatives: any movement of Polish lands to the beginnings of autonomy, not to mention independence, had to start from Vienna.

The presence of numerous Polish kolo in the parliament of Galicia, hypocritically called the Sejm, did not contradict this line in the least: the external signs of "constitutionality" were frankly decorative. But we must remember that in Vienna, with all the thirst for an independent policy, for example, in the Balkans, and therefore in respect of their own subjects, the Slavs, they were still a little afraid of the Berlin ally.

The same person constantly nervously reacted to any steps not even in favor of the Slavic population of the dual monarchy, but to those that at least did not infringe upon the Slavs. The case often came to direct pressure, and not only through diplomatic channels. So, back in April, 1899 on behalf of the German Foreign Ministry considered Holstein (1) to directly threaten Austria-Hungary if it does not strengthen the anti-Slavic course in internal affairs and tries to independently seek rapprochement with Russia. Threaten with the fact that the Hohenzollerns could more quickly reach an agreement with the Romanovs and simply divide the ownership of the Hapsburgs among themselves (2).

But, apparently, it was only a threat. Its real side expressed the aspiration of German imperialism under the cover of Pan-German slogans to annex Austrian lands up to the Adriatic, and to include the rest in the notorious Mitteleurope. It must be said that even reckless Wilhelm II did not dare to press directly on Franz Joseph. However, in the Polish question, this, apparently, was not very necessary. The aged Austrian monarch was actually not much different in his attitude towards the “gonoristymi” Poles from the other two emperors, much younger and much more rigid — Nikolay Romanov and Wilhelm Hohenzollern.

In the end, it was from his submission that even Krakow was deprived not only of republican status, but also of minimal privileges. Projects with the coronation of someone from the Habsburgs in Krakow or Warsaw, which at first glance are very flattering for their subjects, clearly fade before such concrete steps in the opposite direction. The abolition of autonomy in Galicia was all the more offensive for the Poles against the background of the special status gained in Hungary by 1867.

But an even greater anachronism was Schönbrunn’s stubborn reluctance as early as 1916, just a few days before the death of Franz Josef, to include “his” Polish lands in the impromptu Polish Kingdom (3). The part of Poland that was divided into Hapsburg sections (Galicia and Krakow) cannot be considered poor. Coal of the Krakow basin, Velichkinskaya salt fields, a lot of oil and excellent opportunities for the development of hydroelectric power - even in our time there is a good potential, and in the XIX - early XX century altogether.

But for the Austrians it was a hopeless province, the “hinterland”, where industrial goods from Bohemia and Upper Austria should be sold. The relatively normal development began in the 1867 year with the introduction of the Polish administration, but the geographical barrier - the Carpathians and the customs border with Russia continued to play its negative role. Nevertheless, the very fact of the Polish government attracted thousands of people to Krakow, above all the intelligentsia. However, she, under the impression of Galician freedoms, did not even think about separation from Vienna.

Moreover, it was precisely the central government that the Poles relied in their opposition to the Eastern Slavic population of the region - Ukrainians and Ruthenians. The peculiarity of the position of the Poles in Galicia, who for the most part hardly believed in the prospect of the “third” crown, reflected on the rather high popularity of the Social Democrats, who skillfully prepared the political cocktail of national and frankly leftist slogans. It was from among them that the future leader of the liberated Poland, Jozef Pilsudski, emerged.

Independence? This is ballast

Is it any wonder that the overwhelming majority of independent Polish politicians in the 10s of the 20th century, and some politicians, before, somehow relied on Russia. The well-known Polish jurist, moderate socialist Ludwig Krzywicki admitted: “... national democracy already in 1904 rejected the demand of independent Poland as an unnecessary ballast. Polish Socialist Party begins to talk only about autonomy. The public mood has progressed even further. The credibility of Russia was so strong that not without reason the few groups that still retained the old position complained that the worst kind of reconciliation is taking place in Poland - reconciliation with the whole Russian society. ”

And it’s not even the case that two thirds of the Polish lands were ruled by the Romanovs - this was one of the reasons for the overtly anti-Russian position of the radicals, such as Pilsudski. It was just in Russia, where the Poles, even in 1905, did not go to an open revolutionary speech, the question of the independence of Poland had time to really brew, and not only “implicitly”, as mentioned above.

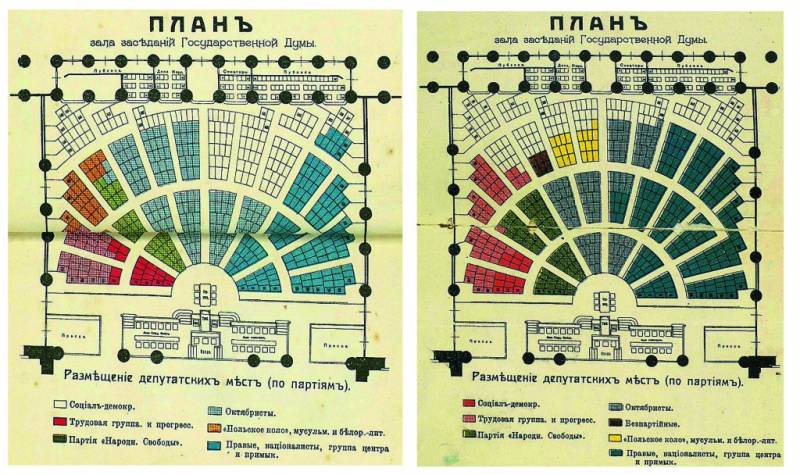

For several years it was widely and openly discussed in the press and in the State Duma. Virtually any legislative act, whether it was a question about the zemstvo or the well-known Stolypin project for the separation of the Kholmshchina, immediately discussed the Polish question as a whole, when discussing it. First of all, the topic of autonomy was touched upon, and this despite the small number of Polish Kolo, even in the First Duma (37 deputies), not to mention the following, where Polish deputies became less and less (4). Let the deputies, once honored with a personal shout from the tsar's uncle, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, fear the very word “autonomy” like fire. After all, in reality, and not on paper, the ideas of political, cultural and economic isolation - this is autonomy.

The Polish Kolo in every new convocation of the State Duma (the composition of the III and IV convocation is shown) had fewer and fewer seats.

For half a century after the tragic events of 1863, the readiness to give Poland at least wide autonomy, and at the most - its own crown, best of all - in the Union with Romanov, was clearly realized by many Russian liberally-minded politicians. The well-known words of Prince Svyatopolk-Mirsky: “Russia does not need Poland”, openly spoken in the State Council already during the war, long before that had been heard more than once from the lips of politicians both in secular salons and in private conversations.

The Russian leaders, of course, kept “genetic memory” about the national liberation uprisings of 1830-31 and 1863 against Poland. (5). However, the low revolutionary activity of the Poles in the 1905-07 years forced not only liberals to take a different look at Poland. Conservatives, who had previously categorically rejected the idea of a “free” Poland, actually accepted it in the days of World War II, albeit in their own way. This position was voiced in the Russian-Polish meeting of Prime Minister I. Goremykin, who cannot be suspected in liberalism: “there is Poznan, etc., there is autonomy, there is no Poznan, there is no autonomy” (6). To which, however, he immediately received a reasonable objection from I.A. Shebeko - Polish State Councilor: “Can the solution of the Polish question be made dependent on the successful outcome of the war?” (7).

The autocrat of the Romanov dynasty from 1815, after the Congress of Vienna, wore the title of the king of Poland among many of his titles - a relic of absolutism, for which he was ashamed not only of his home-grown liberals, but also of his “democratic” allies. However, when the prospect of a clash with Germany and Austria stood in front of Russia at full height, it was decided to put forward common anti-German interests. No, this decision was not made by the emperor, not by the Council of Ministers, or even by the Duma, only by military intelligence.

But it also meant a lot. The future Russian supreme commander-in-chief, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, at that time commander-in-chief of the St. Petersburg military district and the actual head of the military party, fully trusted the scouts. And she in the last pre-war years, perhaps, had more influence than all the political parties combined. It was the grand duke who, according to the memoirs, referring to his adjutant Kotzebue, stated more than once that the Germans would calm down only when Germany, "defeated once and for all, would be divided into small states, amusing themselves with their own tiny royal courts" (8).

Not Helm, but Hill, not a province, but a province

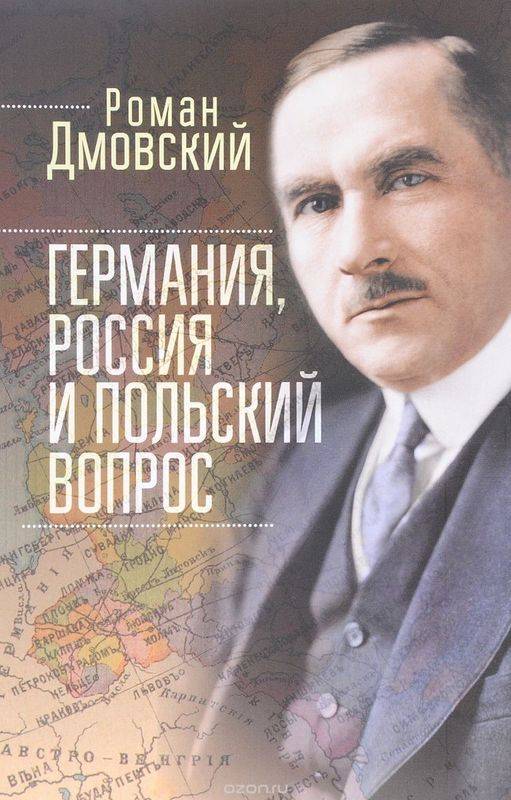

From the height of the imperial throne, the Great-Powers allowed to turn their ardor against the main enemy - Germany. The king, under the impression of the pro-Russian program work of the leader of the Polish national democrats Roman Dmovskiy “Germany, Russia and the Polish Question”, decided to “allow” on a fairly large scale the propaganda of the Polish-Russian rapprochement on an anti-German basis. In this way, non-Slavonic circles hoped to strengthen the position of supporters of the monarchist union with Russia in the Kingdom of Poland and use rapprochement with the Poles as a tool for weakening their rival in the Balkans - Austria-Hungary.

The program work of the ideologist of Polish nationalism, quite loyal to Russia, was released from us only through 100 and beyond

To play the "Polish card" the Russian leaders decided not least because the calm was felt in Russian Poland on the eve of the war. Moreover, against the background of anti-German sentiments in the Kingdom, the economic situation was also quite favorable. Thus, the rates of industrial growth in the Polish provinces were higher than in Great Russia; the Stolypin agrarian transformations, despite arrogant Russification, found fertile ground in Poland.

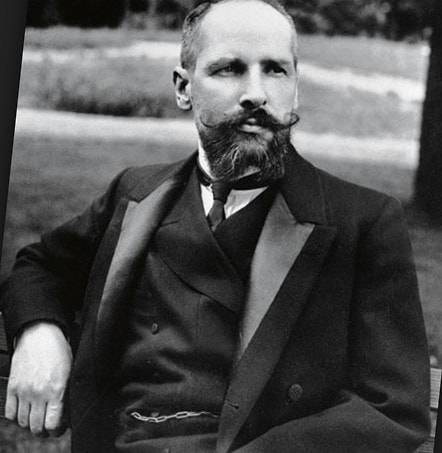

It is characteristic that the prime minister himself adhered to purely nationalistic views, calling the Poles “a weak and incapable nation” (9). Once in the Duma, he sharply laid siege to the same Dmovsky, saying that he was honoring for "the highest happiness of being a subject of Russia." Isn't it too tough considering the fact that in April 1907 of 46 Polish deputies in the Second Duma, with the suggestion of Dmovsky, put forward their very, very loyal proposals to resolve the Polish question?

P.A. Stolypin. A strong premier is not particularly ceremonial with "weak" nations

However, in such loyalty to the royal power the Polish colo was not lonely. Both the Ukrainian community and the deputies from the Lithuanian Democratic Party sought only for autonomy of the resettlement areas of the peoples they represented within the united Russian Empire. Already after Stolypin's death, teaching in Polish was allowed in the gminas, and the Orthodox Church abandoned attempts at expansion in the Wielkopolska lands.

The appetites of the Moscow Patriarchate for the beginning were limited to “Eastern Territories” (under Stalin, they would be called Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia even for decency). The creation of the Kholmsk province, which was often called “edge” in the Russian manner and the actual transfer to the Great Russian lands of the Grodno province, very successfully fit into this strategy.

The very statement of this question in the Russian parliament, which is absolutely unable to do anything real, has caused a “hysteria” among the leaders of the Polish faction in the Duma. Roman Dmovsky and Jan Garusevich were well aware that the Duma debate was just a formality, and the king decided everything for himself long ago. But I decided something just with the filing of the Orthodox hierarchs.

It should be noted that the true background of this project was quite different - to stake out for themselves the “Orthodox lands” for the future. They began to lay the straw not least because the democratic allies of Russia regularly roused the Polish question — at negotiations, at the conclusion of “secret agreements”, and when drawing up military plans.

Well, if allies want it so much - if you please. “Resolve the Polish Question!” - a year before the war the Octobrist “Voice of Moscow” pathetically exclaimed with the title of its editorial. Naturally, not without the knowledge of the yard. And this is the leading press organ of the party, which quite recently unanimously and fully supported Peter Stolypin’s great-power aspirations. The outstanding Russian prime minister, in his frank antipathy towards the Polish Kolo in the Duma and personally to Roman Dmovsky, did not hide the desire to “limit or eliminate the participation of small and impotent nations in the elections”. In the Russian Empire it was not necessary to explain who Stolypin had in mind here in the first place.

However, any shifts towards loosening for Poland were periodically met by Russian leaders in hostility. So, after a long and competently propagated discussion, the city government project for the Polish provinces was safely postponed “until better times”.

In spite of the fact that personally V.N. Kokovtsov, who replaced Stolypin, 27 in November 1913. The State Council failed the bill, believing that no such exceptions could be made for national suburbs. At least, before the Russian lands, self-government, even in its most curtailed form, cannot be introduced anywhere. As a result of a brief hardware intrigue, 30 of January 1914 of Mr. Kokovtsov resigned, although the Polish topic was only one of many reasons for this.

Notes:

1. Holstein Friedrich August (1837-1909), an adviser to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, is actually the deputy minister (1876-1903).

2. Erusalimsky A. Foreign policy and diplomacy of German imperialism at the end of the XIX century, M., 1951, s.545.

3. Shimov Ya. Austro-Hungarian Empire. M., 2003, p. 523.

4. Pavelieva T.Yu. Polish faction in the State Duma of Russia 1906-1914. // Questions stories. 1999. No.3. C.117.

5. Ibid. With. 119.

6. AVPRI, 135 Foundation, op.474, case 79, sheet 4.

7. RGIA, 1276 Foundation, op.11, 19 case, 124 sheet.

8. Quoted by Takman B. August guns. M., 1999, p. 113.

9. Russia, May 26 / June 7 1907

10. Pavelieva T.Yu. Polish faction in the State Duma of Russia 1906-1914 / / Questions of history. 1999. No.3. C. 115.

Information