Russian answer to the "Polish question"

Not France and the United States, and even more so, not the Central Powers, who established the bastard "Regent kingdom" in the east of the Polish lands. The troops of two emperors with German roots until the revolutionary events of November 1918 remained on Polish soil.

In the fall of 1914, the imperial Russian army went to war "against the German one", which did not become the second "native" army, in general it’s bad to imagine what it would fight for. Officially, it was thought that, among other things, for the restoration of a "complete" Poland. Let it be intended to carry out "under the scepter of the Romanovs."

At the end of the 1916 of the year, Nicholas II, by order of the army, recognized the need to re-establish an independent Poland, and the Provisional Government already declared Polish independence "de-jure". And, finally, the government of the people's commissioners made it "de-facto", fixing its decision a little later in the articles of the Brest Peace Treaty.

"We with the Germans have nothing to share, except ... Poland and the Baltic states." After the bad memory of the Berlin Congress, this cruel joke was very popular in the social salons of both Russian capitals. Authorship was attributed to both the celebrated generals Skobelev and Dragomirov, and the ingenious writer of Petersburg Essays, Peter Dolgorukov, who, without embarrassment, called the royal courtyard "bastard."

Later, on the eve of the world massacre, retired Prime Minister Sergei Yulievich Vitte and the Minister of Internal Affairs in his office, Senator Pyotr Nikolayevich Durnovo, as well as a number of other opponents of the war with Germany, spoke in absolutely the same spirit.

But history, as you know, is full of paradoxes ... and irony. Over the course of a century and a half, both in Russia and in Germany “above”, over and over again, the desire to deal with Poland was gained only by force. The same "power" methods of the Russian Empire that under the tsar, which under the communists adhered to with respect to small Baltic countries, were good Germans could really "reach" them only in wartime.

In the end, the Balts and the Poles entered the third millennium proud of their independence, and both empires - and again, Germany, which is gaining strength, and the new "democratic" Russia - are fairly curtailed. We cannot but recognize the current European status-quo. However, it is very difficult to disagree with supporters of a tough national policy - the current frontiers of both great powers do not correspond to their “natural” historical boundaries.

Russia and Poland in the millennial civilizational confrontation of the East and the West have historically dropped the role of a frontier. Through the efforts of the Moscow kingdom, the rigid pragmatic West over the centuries has removed the wild and poorly structured East as far as possible from itself. But at the same time, many European powers, with Poland at the forefront, for centuries did not cease trying to move the “watershed of civilizations” at the same time - of course, at the expense of Russia.

However, Poland, which Europe "endowed" with Latin and Catholic religions, itself experienced considerable pressure from the West. However, perhaps, only once in its history - at the beginning of the 15th century, Poland responded to this by direct cooperation with the Russians.

But this happened only at that moment when the country itself, with the name of Rzeczpospolita, or more precisely, Polska Rzeczpospolita, was by no means a Polish national state. It was a kind, let's call it so, the "semi-Slavic" conglomerate of Lithuania and the western branch of the collapsing Golden Horde.

Despite the notorious blood relationship, the similarity of cultures and language, it is difficult to expect peaceful coexistence from the two powers, who practically had no choice in determining the main vector of their policies. The only example of joint opposition to the West - Grunewald, unfortunately, remained the exception that only proved the rule.

However, the Stalinist “Polish Army” is probably another exception, of course, different, and in fact, in spirit. And the fact that the Polish kings claimed the Russian throne was not an adventure at all, but only a logical continuation of the desire to "push back" the East.

The Muscovites responded to the Poles in return and were also not averse to climbing to the Polish throne. Or themselves, and Ivan the Terrible - there is no exception, but the most real contender, or by putting his protege on him.

If the Polish white eagle, regardless of the historical conjuncture, always looked to the West, then for the Russians only two centuries after the Mongol yoke, no matter how it was characterized by Lev Gumilyov or "alternatives" Fomenko and Nosovich, it was time to turn in that direction. Previously, internal disturbances were not allowed.

In practice, Russia had to complete its deeply "expensive" oriental expansion oriented only to the distant future in order to gain the right to such a "European" sovereign as Peter the Great. By that time, the winged horsemen of Jan Sobieski had already accomplished their last feat for the glory of Europe, defeating the many thousands of Turkish army under the walls of Vienna.

Polish – Lithuanian Commonwealth, torn by the gongolian gentry from the inside, in fact only waited for its sad fate. It was not by chance that Karl XII marched from Pomerania to the walls of Poltava with such ease, and Menshikov’s dragoons rode along the Polish lands to Holstein itself.

The Russians throughout the 18th century used the territory of Mazovia and Wielkopolska as a semi-semi-springboard for their European exertions. Europe, waving a hand at the Poles, only a couple of times tried to move to the East. But even the Prussians, with the restless Frederick the Great and his brilliant General Seidlitz, the leader of the magnificent hussars, were afraid to go further than Poznan.

Soon, when fermentation on Polish lands threatened to turn into something like “Pugachev”, the energetic rulers of Russia and Prussia, Catherine II and Frederick, also the Second, responded very vividly to the appeals of the Polish nobility to restore order in Warsaw and Krakow. They quickly turned two sections of the Commonwealth.

No wonder that Catherine and Friedrich received the right to be called Great at their contemporaries. However, the Russian empress only returned the Russian lands to her crown. "Denied returns!" - With these words, she decided the fate of Belarus, and Alexander I had already slaughtered primordial Poland to Russia, and that was only because it was too tough for the Prussians.

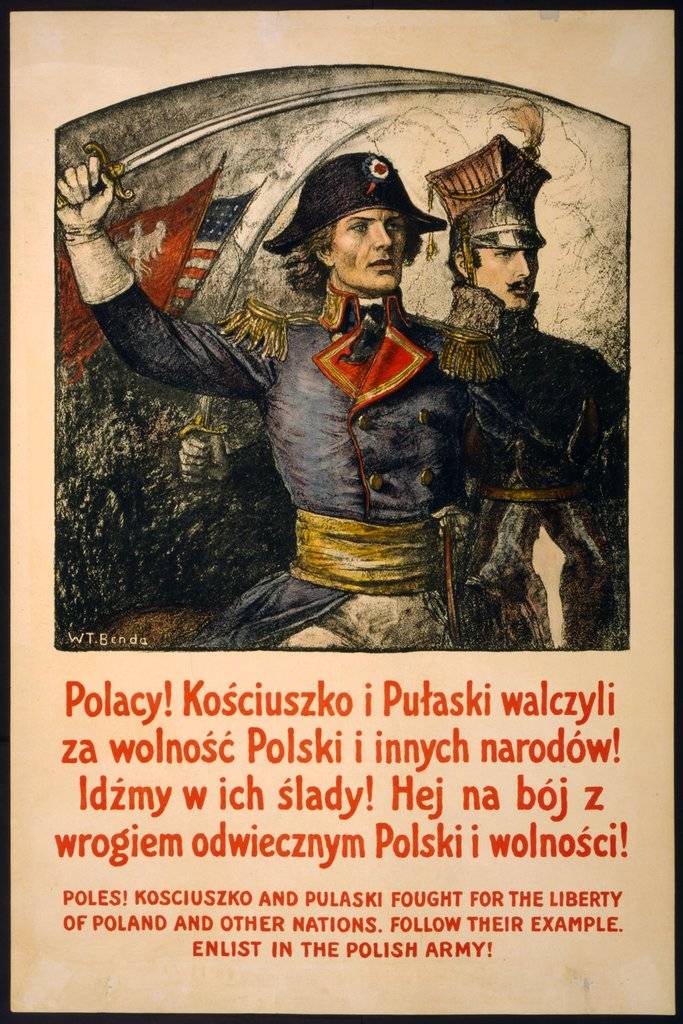

The third partition of Poland was only the end of the first two, but it was he who caused the popular uprising of Tadeusz Kosciuszko - a popular one, but this only made it more bloody. Historians have repeatedly refuted the false stories about the brutality of the brilliant Suvorov, but to force the Poles to abandon their dislike for him and his Cossacks, about the same thing as instilling in Russians a love for Pilsudski.

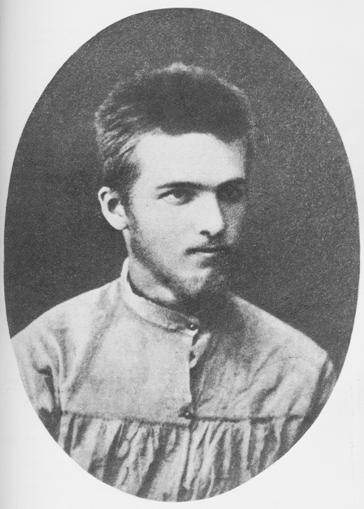

More recently, under his portrait did not have to make a signature - Tadeusz Kosciuszko

However, it was not immediately after the three divisions of Poland that the final divorce of two Slavic peoples became one of the key problems of European politics. The fact that the Poles and the Russians were not together was finally clear exactly 200 years ago - since Napoleon made an attempt to recreate Poland. However, the emperor of the French pointedly, in order not to irritate Austria and Russia, called it the Duchy of Warsaw and put the Saxon king on the throne.

Since then, all attempts to “write down” the Poles into Russians have run up against harsh rejection. Well, the gonor gentry, having lost a century-long confrontation with its eastern neighbor, completely forgot about the idea of reigning in Moscow. By the way, sometimes the Muscovites themselves had nothing against the gentry on the Moscow throne, and it was they who called the first of the Lzhedmitry to the Mother See.

It would seem that the Polesia swamps and the Carpathians are suitable for the role of the "natural borders" of Poland and Russia, no worse than the Alpine Mountains or the Rhine for France. But the peoples who settled on both sides of these borders turned out to be too Slavic energetic and enterprising.

The “Slavic dispute” more than once seemed to be completed almost forever, but in the end, when the German powers intervened unceremoniously and eagerly, it turned into three tragic sections of the Commonwealth. Then it turned into one of the most "sick" issues in Europe - Polish.

The flashing was under Tadeusz Kosciuszko, and then under Napoleon, hope, so it remained for Poles hope. Subsequently, hope turned into a beautiful legend, into a dream, which many believe is hardly feasible.

In a century of great empires, the "weak" (according to Stolypin) nations did not even get the right to dream. Only world war replaced the era of empires with the era of nationalities, and the Poles somehow managed to regain their place in the new Europe.

In many ways, the “green light” gave two Russian revolutions to the revival of Poland. But without the preemptive participation of the Russian empire, which for a hundred or more years included most of the Polish lands, the matter was not done.

The tsarist bureaucracy itself in many ways created for itself the "Polish problem", annually gradually destroying even those limited freedoms that Emperor Alexander I the Blessed granted to Poland. The “organic status” of his successor on the throne, Nikolai Pavlovich, was written in blood as a result of the 1830-31 fratricidal war, but he retained many rights for the Poles, which the Great Russians then could not even dream of.

After that, the rebirth of the nobility did not support the revolutionary outburst of 1848 of the year, but rebelled later - when not only Polish, but also Russian peasants received freedom from the tsar-liberator. The organizers of the adventurous "Rebellion-1863" did not leave Alexander II any other way than to deprive the Kingdom of the last hints of autonomy.

It is not by chance that even Polish historians, inclined to idealize the struggle for independence, differ so radically in their assessment of the events of the year. By the end of the 19th century, in enlightened houses, for example, in the family of Pilsudski, the “uprising” was categorically considered a mistake, moreover, a crime.

Like any decent dictator, Jozef Pilsudski began as a revolutionary - the future "head of state" in Siberia

A great success for the Russian imperial power was the passivity of the Poles in 1905, when only Lodz and Silesia really supported the revolutionaries of Moscow and St. Petersburg. But, entering into the World War, it was practically impossible for Russia to leave the “Polish question” unresolved. Without taking it "from above", one could only expect one solution - "from below."

The threat that the Germans or the Austrians "will understand" the Poles frightened Nicholas II and his ministers much less than the prospect of another revolution. After all, in it the "nationals" are unlikely to remain neutral, and certainly never take the side of the authorities.

And yet, the Poles themselves in those years were waiting for a solution to "their" issue, primarily from Russia. A little later, having experienced disappointment in the efforts of the tsarist bureaucracy, most of them relied on the allies, first on the French, as if by the principle of "old love does not rust," then on the Americans.

The Austrian combinations with the triune monarchy of the Poles almost did not care - the weakness of the Habsburg empire was clear to them without explanation. And to rely on the Germans and did not have at all - for decades, following the precepts of the Iron Chancellor Bismarck, the Poles tried to Germanize. And, by the way, it is not always unsuccessful - even after all the troubles of the 20th century, traces of German traditions can still be traced in the lifestyle of the absolutely Polish population of Silesia, as well as of Pomerania and the lands of the former Poznan duchy.

Paying tribute to the purely German ability to organize life, we note that it is with this - the stubborn desire to promote on the conquered lands all the "truly German" Hohenzollerns, by the way, were strikingly different from the Romanovs. The calls of the latter to strengthen Slavic unity are, you see, not a synonym for primitive Russification.

However, there were plenty of masters and those who wanted to cross the "Pole to the Ruska" among the royal subjects. Just the creeping, really not sanctioned from above, the desire of large and small officials, among whom there were many Poles by nationality, to root "everything Russian", at least in the disputed lands, was backfired by the Russian hard rejection of "all Russian".

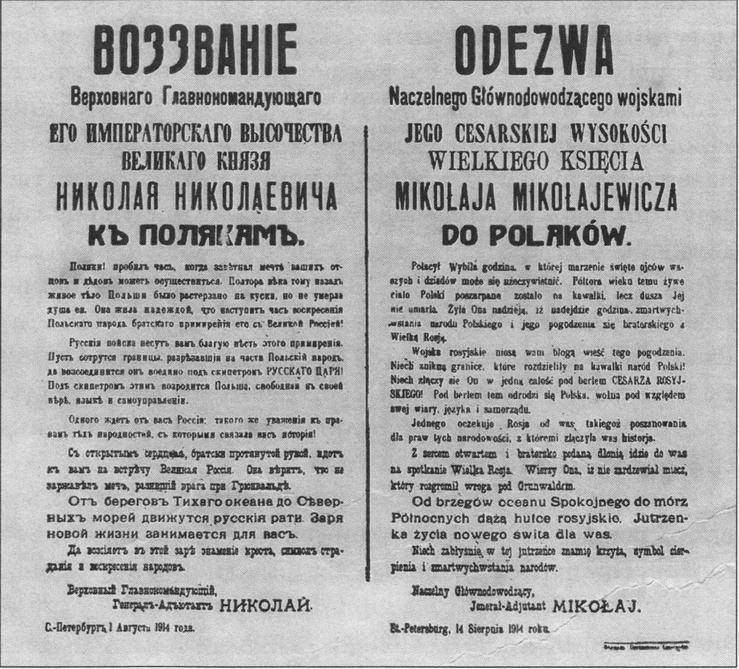

The World War sharply aggravated the “matured” Polish question, which explains the surprising promptness with which the first public act was adopted, which addressed directly to the Poles - the famous grand duke's appeal. After that, the Polish question was by no means "pushed into the back of the box", as some researchers believe.

"Appeal to the Poles" Supreme Commander of the Russian army of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich

Despite the desire to “postpone” the Polish question, which constantly overwhelmed Nicholas II, when he frankly waited that the issue would be resolved by itself and the “Appeal” would be enough for that, he was repeatedly considered in the State Duma, in the Government and in the State Council . But a specially created commission of Russian and Polish representatives, assembled to determine the "beginnings" of Polish autonomy, did not formally decide anything, confining itself to recommendations of a rather general nature.

Moreover, even formal recommendations turned out to be enough for Nicholas II to answer informally to the proclamation of the Polish Kingdom by the Germans and the Austrians ... exclusively on the lands of the Russian Empire.

In the famous order for the army, which was personally marked by the sovereign on December 25 (12 in the old style - the day of St. Spyridon-turn), it was unequivocally stated that "Russia's vital interests are inseparable from the establishment of freedom of navigation through the straits of Constantinople and the Dardanelles and from our intentions to create a free Poland from its three currently divided provinces."

The Supreme Commander admitted that "Russia’s attainment of the tasks created by the war, the possession of Tsargrad and the straits, as well as the creation of a free Poland from all three of its disparate regions, has not yet been secured." Is it any wonder that in many Polish homes, despite the Austro-German occupation, this order of Nicholas II was hung in the festive framework next to the icons.

The Provisional Government, which replaced the Romanov bureaucracy, and after it the Bolsheviks, surprisingly decisively disassociated themselves from their western "colony" - Poland. But even then, most likely, only because they had enough headache without it. Although it is impossible not to notice that all the documentation on Polish autonomy was prepared in the Russian Foreign Ministry (even the choice of the imperial department is typical - the ministry is not internal but foreign affairs) before February 1917, which helped the new foreign minister Milyukov so “easily” resolve the difficult Polish question.

But, as soon as Russia gained strength, the imperial thinking again gained the upper hand, and in its most aggressive form. And if such "great powers" like Denikin and Wrangel lost more from this than they gained, then Stalin "with comrades", no matter what, returned Poland to the sphere of influence of Russia.

And let this Russia was already Soviet, but no less "great and indivisible." However, condemning the Russian "imperials" in any of their political clothes, it must be admitted that the European powers, and the Poles themselves for centuries did not leave Russia any chance to go on the Polish question in a different way. But this, you see, is a completely separate topic.

Yet civilized, and, apparently, the final, divorce of the two largest Slavic states took place - towards the end of the 20th century. We plan to talk about the first steps to this that were taken between August 1914 and October 1917 in a series of subsequent essays on the “Polish issue”. How long this series will be depends only on our readers.

We immediately recognize that the analysis of the “question” will be obviously subjective, that is, from the standpoint of the Russian researcher. The author is fully aware that "giving the word" in him was possible only to people quite well-known, at best - reporters from leading Russian and European newspapers.

The voice of nations, without which it is difficult to truly objectively assess national relations, the author is forced to leave “behind the scenes” for the time being. This, too, is the subject of a special fundamental research that can be done only by a team of professionals.

The current neighborhood of Russia and Poland, even if there is a Belarusian “buffer,” no matter how hard the head of the Union Republic, “pro-Russian” by definition, resists, is the easiest to describe as a “cold world.” Peace is always better than war, and it is certainly based, among other things, on what the best representatives of Russia and Poland managed to achieve at the beginning of the last century.

Now Poland has once again swung towards Germany. But even this does not allow us to forget that the “Western scenario”, whether German, French, American or the current European Union, has never guaranteed Poland a position “on equal footing” with the leading powers of the old continent.

And Russia, even after taking the majority of Poland after the victory over Napoleon, “for themselves”, provided the Poles much more than the Russians themselves could count on in the empire. In the same, that almost everything that Alexander the Blessed has "bestowed" on them, the Poles have lost, they are to blame no less than the Russians.

From Stalin in the 1945 year, Poland, oddly enough, in the state plan received much more than what its new leaders could count on. And the Polish population got such a German inheritance, which after the Great Victory, none of the Soviet people should have even counted.

Even taking into account the new era of frank flirting of Poland with the West, given the fact that we now do not even have a common border, the Russian factor will always be present in the Polish consciousness, and therefore in Polish politics and economics as almost the most important. For Russia, the “Polish question” only in critical years - 1830, 1863, or 1920, acquired paramount importance, and probably will be better both for our country and Poland, so that it never becomes the main .

Information