The first major victory of Napoleon. The start of the brilliant Italian campaign

General Napoleon Bonaparte

220 years ago, 12 April 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte won his first major victory in the battle of Montenotte. The battle of Montenotta was Bonaparte's first important victory, which he won during his first military campaign (Italian campaign) as an independent commander-in-chief. Napoleon himself said: "Our lineage comes from Montenotta." It was the Italian campaign that made Napoleon's name known throughout Europe, then for the first time, his leadership talent was revealed in all its glory. No wonder that at the height of the Italian campaign, the great Russian commander Alexander Suvorov will say: “He's walking far, it's time to calm the young man!”

prehistory

The young French general literally dreamed of the Italian campaign. While still the commander of the garrison in Paris, he, together with a member of the Directorate Lazar Carnot, prepared a plan for a campaign to Italy. Bonaparte was a supporter of active, offensive war, urging dignitaries in the need to preempt the enemy, anti-French alliance. The anti-French coalition then included England, Austria, Russia, the Sardinian kingdom (Piedmont), the Kingdom of both Sicilies and several German states - Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, etc.

The directory (the then French government), like the whole of Western Europe, believed that the main front in 1796 would be in western and southwestern Germany. From there, the French planned to invade the Austrian lands proper. For this campaign, the best French units with the best generals were assembled, of which two armies were formed under the command of generals Jean Jourdan and Jean Moreau, totaling about 155 thousand soldiers. These troops were to pave the way to Vienna. For these troops did not spare the means, equipment, their transport was well organized.

At this time, the commander of the Paris garrison, Bonaparte, made a “Note on the Italian Army” in which he proposed invading Northern Italy from southern France in order to divert the forces of the anti-French coalition from the German theater of operations and ensure successful actions of the main forces. These proposals were accepted by the Directorate and sent to execution by General Scherer, who then commanded the Italian army. But Scherer did not like the plan, he knew the condition of his troops very well. “Let the one who compiled it do it,” said Scherer.

The Directory was not particularly interested in the plan of invasion of Northern Italy through the south of France. The Italian front was considered secondary. But we took into account that in this direction it would be useful to hold an active demonstration in order to force the Austrian command to split up its forces, nothing more. Therefore, it was decided to send the Italian army against the Austrians and the Sardinian king. Formally, the Italian army was tasked with capturing Piedmont and Lombardy, after which it would join the main forces through Tirol and Bavaria to capture Vienna. However, there were no great hopes for the actions of the Italian in Paris. And even more so then no one could have foreseen that it was in Italy that the decisive events of this campaign would unfold. When the question arose of whom to appoint the commander-in-chief on this secondary sector of the front, Carnot named Bonaparte. The remaining directors easily agreed, because none of the more well-known generals for this appointment wanted to. The direction was considered unpromising and did not want to spoil their reputation.

Thus, the troops should have been led by Napoleon, who replaced Scherer. 2 March 1796 was proposed by Carnot Napoleon Bonaparte as Commander-in-Chief of the Italian Army. Already on March 11, three days after their own wedding, the new commander-in-chief rushed to their destination. The dream of a young general came true, Bonaparte got his star chance, and he did not miss it.

27 March Napoleon arrived in Nice, which was the main headquarters of the Italian army. Sherer handed over the army to him and brought in the case: 106 thousand soldiers were formally registered in the army (four infantry and two cavalry divisions under the command of generals Massena, Augereau, La Harpe, Seryurye, Stenzhel and Kilmen), but in reality there were 38 thousand. In addition, of these 8 thousand were garrison of Nice and the coastal zone, these troops could not be led to the offensive. As a result, in Italy it was possible to take no more than 25-30 thousand soldiers. The rest of the army were "dead souls" - they died, were sick, were captured or deserted. In particular, two cavalry divisions were formally listed in the Southern Army, but in both of them there were only 2,5 thousand sabers. Yes, and the remaining troops were similar not to the army, but to the crowd of ragged people. It was during this period that the French Quartermaster Department came to an extreme degree of predation and theft. The army was already considered secondary, therefore it was supplied according to the residual principle, but what was released was quickly and brazenly plundered. Some parts were on the verge of rebellion due to poverty. So Bonaparte just arrived, as he was told that one battalion refused to execute the order for redeployment, since none of the soldiers had boots. The collapse in the field of material supply was accompanied by a general collapse of discipline and fighting spirit. The location of the army was exhausted by requisition.

The army did not have enough ammunition, food and equipment, the money the soldiers did not pay for a long time. The artillery park consisted of all 30 guns. Napoleon had to solve the most difficult task: to feed, clothe, tidy the army and do it during the march, as he was not going to delay. The situation could be complicated by friction with other generals. Augereau and Massena, like the others, would willingly obey the older, or more honored commander, rather than the 27-year-old general. In their eyes, he was only a capable artilleryman, a commander who served well under Toulon and noted the shooting of the rioters. He was even given a few offensive nicknames, such as “lame”, “General vandemier”, etc. However, Bonaparte could put himself in such a way that he soon broke the will of all, regardless of rank and rank.

Bonaparte immediately and brutally began the fight against theft. He reported to the Directory: "I have to shoot often." But a much greater effect was brought not by executions, but by Bonaparte’s aspiration to restore order. The soldiers immediately noticed this, and discipline was restored. He decided the problem with the supply of the army. The general from the very beginning believed that the war should feed itself. To interest the soldier in the campaign, Napoleon declared: “Soldiers, you are not dressed, you are poorly fed ... I want to lead you to the most fertile countries in the world” (“From the appeal to the Italian army”). Napoleon was able to explain to the soldiers that their support in this war depended on them. And he knew how to find an approach to the soul of a soldier. Bonaparte's army had no choice, it could only go forward. Hunger and deprivation drove the soldiers, razbutye and stripped, with heavy guns at the ready, outwardly more like a horde of beggars and marauders than a regular army, they could only hope to win, because defeat meant death to them.

Campaign start

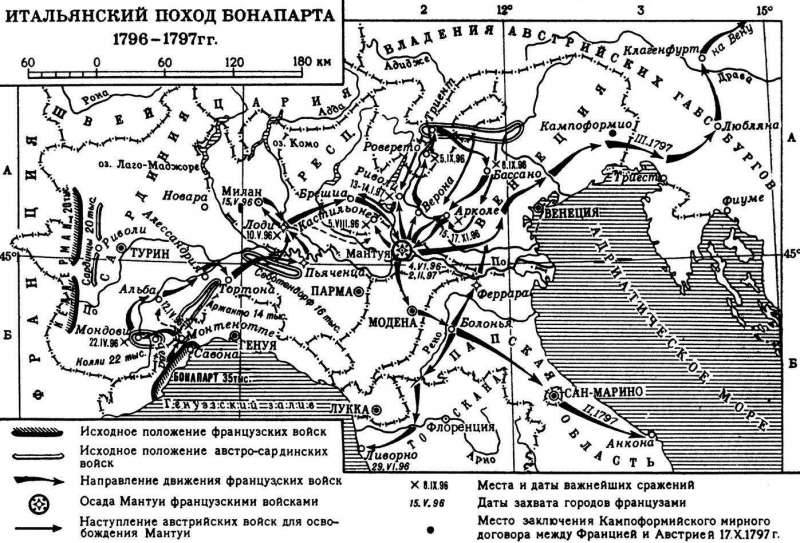

The Italian theater represented the low-lying valley of the Po, bordered from the northwest and southwest by the Alps, and in the south by the Ligurian Apennines. The river Po, which flows from west to east, is a serious obstacle, with a number of fortresses along both its banks. Valley of Po is divided into 2 parts: the northern plain, relatively populated and rich; it is crossed in the meridional direction by the left tributaries of the Po, representing natural defensive lines; and southern - smaller in area, filled with mountain spurs; this part was less rich and less populated. The Ligurian Apennines descend steeply to the sea, forming the seaside Riviera. From the Riviera to the valley of the Po led the most important roads: from Nice to Cuneo, from Savona to Cherasco and Alessandria and from Genoa to Alessandria. The coastal road (Corniche), which serves as a communication with France, was blurred and here wax could be attacked from the sea.

At the Italian Theater there were two French armies: the alpine Kellermann (20 thousand), which was supposed to protect the mountain passes from the side of Piedmont, and General Bonaparte. Against Kellerman was the Duke of Aosta with 20 thousand soldiers; against Napoleon, the Austro-Sardinian army of Johann Beaulieu. Austro-Sardinian forces numbered about 80 thousand people with 200 guns. An Austrian Belgian-born general Beaulieu planned to invade the Riviera and throw the French across the Var. To this end, the Sardinian squad Colli and the right wing of Argento were to move south towards the Apennines, and Beaulieu with the left wing - through the Boquet passage and the outskirts of Genoa - to the Riviera. The plan was complicated, as the army stretched out over a large area, it was crushed and the blow weakened.

For his part, Napoleon also decided to attack. Since 1794, he has compiled several carefully developed options for offensive operations in Italy. For two years I studied the map of the future theater of warfare perfectly and knew it, as Clausewitz put it, as “my own pocket”. His plan was simple. Napoleon decided to break through the stretched arrangement of the Allies and then attack the Sardinians of Collie or the Austrians of Beaulieu. His plan was to defeat the opposing forces separately: first defeat the Piedmontese army and force Piedmont to capitulate, then strike the Austrians. In order to win, it was necessary to surpass the enemy in speed and maneuverability, to seize the strategic initiative. Napoleon was not a pioneer in this sphere; Suvorov acted in the same way. Thus, both armies decided to advance.

On April 5, 1796, Napoleon moved troops across the Alps. From the very beginning, Napoleon showed bold courage and the ability to take risks. The army went the shortest, but also the most dangerous way - along the coastal edge of the Alps (the so-called "Karniz"). Here the army was in danger of being hit by the British fleet. The risk paid off; the trip to Karniz on April 5–9, 1796, went smoothly. The French successfully entered Italy. The Austro-Piedmontese command and thought did not allow the enemy to decide on such a risk.

Thus, in order to defeat Napoleon, it was necessary to act as quickly as possible and seize the initiative from the enemy. It was necessary to capture Turin and Milan, to force Sardinia to surrender. Rich Lombardy could provide resources for further campaigns.

Battle of Montenotta

Immediately after the transition, he directed General Seryurye's division to observe the positions of General Colley near Cheva, and he concentrated the divisions of La Harpe, Massena and Augereau in Savona, demonstrating the intention to move to Genoa. The vanguard of the Lagarp division under the command of General Chervoni advanced even further and captured Voltri.

The Austrian commander-in-chief, deceived about the intentions of the French army, 11 began active operations on April to drive the French out of Northern Italy. He moved his main apartment in Novi and divided the troops into three parts. The right flank of the Piedmontese under the command of General Colley with the main apartment in Cheva, received the task of defending the Stura and Tanaro rivers. The center under the command of Argento (D'Arzhanto) marched on Montenotta to cut off the French army during its intended march towards Genoa, crashing down on its left flank. Personally, 72-year-old Beaulieu with his left flank moved to the Voltri - to save Genoa. As a result, Beaulieu even more dispersed his strength. There were no communications between his left flank and the center. And the French army, on the contrary, was positioned in such a way that it could concentrate in a few hours and attack with all its might on the separate corps of the enemy. This is what Napoleon Bonaparte wanted for his demonstration. He created a winning situation. All that followed, historians later call "six victories in six days."

As a result, a French brigade under the command of General Chervoni advanced on Genoa (about 2 thousand soldiers with 8 guns). The Austrian commander decided to crush parts of Chervoni, throwing the French away from Genoa, and then regrouping the troops from Alessandria to strike at Napoleon’s main forces. The division of General Argento was directed against Chervoni, totaling about 4,5 thousand people with 12 guns.

10 April Austrians approached the French positions near the village of "Night Mountain" (Montenotto). Argento planned to capture Savona and cut the Savona road, which ran along the seashore and led to Genoa. The French were informed by the intelligence that the enemy was approaching and prepared for defense by building three redoubts. In this direction, the defense kept the detachment of Colonel Rampon. Around noon, 11, April, Austrians knocked over the advanced patrols of the French and hit the fortifications. But the French repulsed three enemy attacks. Argento withdrew the troops to regroup them and try to surround the enemy.

On the same day, the other forces of Chervoni repelled the Beauli attack at the Voltri Castle. A strong position helped restrain superior enemy forces. By the end of the day, Chervoni withdrew and merged with the division of La Harp. At the same time, the detachment of Rampon was reinforced, behind its redoubts they deployed a second line of fortifications.

On the night of April 12, Napoleon threw Massena and Augereau's divisions across the Cadibon pass. By morning, the division of D'Arzhanto was surrounded and in the minority, the French forces had grown to 10 thousand people. Early in the morning of April 12, the French hit the Austrians: General La Harpe led a frontal attack on the enemy’s positions, and General Massena hit the right flank. When D'Argentino realized the danger of the situation, it was already too late. The Austrian division suffered a complete defeat: about 1 thousand people were killed and wounded, 2 thousand were captured. The remnants of the division Argento in disorder retreated to Dego. 5 cannons and 4 banners were captured. Losses of the French army - 500 people killed and wounded.

Meanwhile, Beaulieu entered the Voltri, but no one was there. It was not until the afternoon of April 13 that he learned about the defeat at Montenotte and about the exit of the French into Piedmont. Beaulieu turned his troops back, but he had to walk almost two days on bad roads in order to return to the main events.

This was Napoleon's first victory during the Italian campaign, which set the tone for the entire campaign. Bonaparte later said: "Our lineage comes from Montenotto." The main thing was not even a victory over the enemy, but the formation of a winning army. Victory in the battle of Montenotta was of great psychological importance for the French army, half-starved, raspyutye French soldiers believed in themselves, defeating a strong opponent. The French believed in their seemingly odd commander. Beaulieu lost the strategic initiative and began to withdraw his troops. The French commander in chief was given the opportunity to strike at the Sardinian troops. In Vienna, they were perplexed, but they considered what happened to be an accident. The coalition forces still had a double quantitative superiority over the enemy.

Colonel Rampon Protects Monte-Legino Redoubt

To be continued ...

Information