Anglo-French naval rivalry. Battle at Beachy Head 10 July 1690 of the year

At the end of the seventeenth century, the heyday of the absolutism of Louis XIV brought France to the military and political power. The expansion of the colonial system, the development of the state apparatus, and the successful appointments to important government posts made it possible to achieve the welfare used to achieve foreign policy goals. England, this ascending and defiant rival, was disorganized by a whole series of internal public upheavals, more recently powerful, Spain was fading, its star was rolling up on the political horizon.

Where there was no need for the use of force, gold, which so far has been in abundance, went to work. The growth of the strength of France at a certain stage began to greatly disturb its close and distant neighbors. The last straw that broke the tide of anxiety and fear was the abolition of the so-called Nantes edict in 1685. The Huguenan Protestants were deprived of all the rights previously granted to them. Such a tough, but, incidentally, expected step made us seriously think about our security as the nearest neighbor of France, the Protestant Netherlands. However, the growing ambitions of Versailles turned a number of Catholic states against him. The Pope himself expressed secret support in curbing the appetites of the ambitious Louis XIV. In 1686, a secret agreement was reached in Augsburg between France, the Netherlands, the Holy Roman Empire, Sweden, Brandenburg and Spain against France. Soon most of the German principalities joined this alliance. League members pledged to deploy military contingents in the event that Louis attacked any of them. The wind of the next big European war was approaching.

The master of Versailles and the kingdom of France did not expect to be pushed hard and unfriendly at his door. The inconvenient and, moreover, restless neighbor, the state stagger of the Netherlands, William III of Orange, did not leave any hope of mastering the English throne. First, his mother, Maria Henrietta Stewart, was the daughter of the English King Charles I, and secondly, the Shtgalger himself was married to the daughter of the then King of England, James II. Knowing how much William was absorbed in his plans to deprive his uncle and father-in-law of the crown, Louis was the first to strike. In a businesslike way he intervened in the dispute over the choice of a new Cologne archbishop, and without advertising his plans to place one of his sons at the head of the Holy Roman Empire, the sun king, without declaring war, begins fighting in September 1688. Battalions with golden lilies rushing in the wind forced the Rhine.

English Gambit

While Louis played the muscles of the 80-thousandth army marching across the Palatinate, William of Orange finally decided. His determination to become king was reinforced not only by his dynastic closeness to Jacob II. The fact is that the king of England, being a Catholic, during the years of his reign very sharply turned the local society against himself with an inept and too zealous policy in a religious issue. The Anglican country, already unaccustomed to Catholicism and all the attributes attached to it, was annoyed and displeased with its king. Jacob II, who placed Catholics in many posts (the main criterion was not talent, but devotion and religion), did not realize what was happening to him in the state. The zealous subordinates reassured the king with reports in the spirit of "In London, everything is calm." But shtatgalter through many spies (in most, voluntary) was well aware of what is happening.

The landing plans in England were kept secret until recently. In the ports of Holland 31 battleships, 16 frigates and almost 400 transports were concentrated and equipped. The Dutch admiral Cornelis Evertsen (son of Cornelis Evertsen the Elder) was only at the last moment dedicated to the design of the expedition. General command fleet carried out by Admiral Herbert who fled from England - this decision was made for political reasons. An army of 11 thousand people and 4 thousand horses was put on transports. The ground forces were also commanded by an emigrant, Marshal Schomberg, who had fled the Huguenot from France. An invasion force with such an international command left the coast of Holland on November 10, 1688, and on November 15 began landing on the English coast in the Dartmouth region. In terms of risk and audacity, the plan of William of Orange can be compared with the famous escape of Napoleon from the island of Elba and the next 100 days. In both cases, the landing party was waiting for an enthusiastic reception. The English fleet, concentrated at the mouth of the Thames, did not budge to oppose the Dutch. Catholic commanders were taken into custody. Not meeting with resistance, William of Orange December 18, 1688 triumphantly drove into London. February 18, 1689 he was solemnly proclaimed king of England. Jacob II, deprived of the support of troops and the nobility, fled with a group of associates to France. The monarch, who had lost the throne, did not unreasonably count on the help of Louis XIV, who sympathized with him. As early as November 16, 1689, the day after the landing of William, France declared war on the General States. Its ground forces were deployed in Germany - and at the beginning of the war, already taking shape as a pan-European, everything was limited to political attacks.

The French fleet, through the tireless efforts of Minister Colbert, reached the heights in both shipbuilding and military operations. Well-equipped arsenals and shipyards, protected harbors, numerous and trained officer corps - all this, coupled with excellent qualitative and quantitative composition, made the French fleet almost the strongest in Europe. All this huge military machine, along with a large army absorbed a lot of resources. With the death of Colbert in 1683, his son, the Marquis de Senyele, took the place. Money for the French naval component began to be released less, but the fleet was still strong and numerous.

With the beginning of the war, the naval minister and a number of military dignitaries begged Louis XIV to bring the ships into the sea. The threat from the French squadrons could easily discourage any adventurous ventures about landing in England, and Wilhelm would have been quietly seated in Holland. However, fascinated by the land company that was gaining momentum, the king did not heed the sensible arguments of his subordinates, and soon he had to give hospitality to the fleeting Yakov. While Louis consoled the royal political émigré, his opponents began to urgently put in order their own naval forces. England and Holland agreed to put up the 80 of the battleships (30 of them were the expeditionary squadron on the Mediterranean), 24 frigate and 12 large firefighters. Most of these ships were English. On land, the Dutch put at least 100 thousand soldiers under the gun, while England put no more than 40 thousand soldiers. The deployment and preparation of the fleets was slow enough - the Dutch rebuilt part of their ships from the merchant, the British felt the need for material and technical support.

The French fleet showed no excessive activity for the next 1689 year. Wilhelm was reasonably afraid of offensive action by a superior enemy, but the expected landing of the French landing force in England did not take place. Louis XIV, who decided to restore Jacob to the throne, pointedly did not declare war on England, considering it occupied by William of Orange. However, such cleverly woven diplomatic patterns did not cancel the fact that England was the main enemy at sea.

In March 1689, Jacob II landed in the Cork region (Ireland) along with 7 thousands of people. Ireland was a Catholic country, and the returning king was greeted with sincere joy. Jacob’s position was not hopeless, and he had a chance of revenge. The troubled Scotland was seething, and partisan detachments of Jacobite Catholics were operating in England itself. The late attempt of the English fleet to prevent the landing was easily repulsed by the French squadron under the command of Lieutenant General Chateau-Renault. Having driven off the British, the French, after leaning a little off the coast of Ireland, returned to Brest. Taking advantage of the absence of the enemy, the British squadron of Captain John Ruka carried out a cruise around Ireland, severely harming the sea communications of Jacob, along which supporters flocked to him and supplies were carried out.

While the hands were unsuccessfully “trawling” the coastal waters, the French carried out the concentration of forces in their Atlantic bases. 9 June 1689, the 20 of the battleships commanded by the Comte de Tourville, and 31 July, this squadron successfully arrived in Brest, bringing the number of the main forces of the French fleet in 70 battleships out of Toulon. Comte de Tourville had a great military experience. Having started his naval career in 17 years, a privateer, a pirate hunter, a brilliant officer and commander, a shipbuilder and tactician, Tourville was undoubtedly the best French naval commander at that time. Produced as vice-admiral, the count was appointed to command the main forces of the French fleet, called the Ocean Fleet. Several times Tourville went to sea, but the British avoided a decisive battle, concentrating on escorting merchant caravans. However, the French also did not feel ready to fully clarify the relationship.

Vice Admiral Comte de Tourville, or "Fleet in being"

Since the beginning of 1690, the French command has focused efforts on raising the level of combat capability of its fleet to the maximum level. Turville, who came from the Mediterranean, constantly improving his crews with various trainings and exercises, found the level of training of the Brest squadron unsatisfactory. In anticipation of the new company loomed two tasks that deserve close attention. Either focus the fleet's efforts on ensuring the unimpeded supply of the troops of Jacob II in Ireland, or the battle with the Allied fleet and the conquest of supremacy at sea. Tourville firmly insisted on the second scenario, because without its implementation, there was a constant threat to all communications connecting Jacob’s army and the French ports of support. After some thought, Louis made the right decision in principle: first attack the English fleet, then neutralize the Dutch, and after that, disembark directly in England. Construction of large galleys 15 began in Rochefort, troops and transports were also there. The equipment and finishing of the linear forces was inadequate, since the arsenals did not have all the necessary things - the cuts in funding had an effect, because the army absorbed most of the military spending.

In his calculations, Louis did not take into account the important, but, as it turned out, very significant details. In addition to the conquest of dominance at sea, the French fleet had to protect Ireland proper from a possible landing of William, who was already preparing to eliminate this Catholic threat. In March 1690, the French were able to transfer Yakov to help 7 more thousand people, and the British began to think even more about the Irish problem. While under the shrill of saws, the hammering of blacksmiths and the cursing of sailing shops, French naval power was becoming more and more distinct, a lover of daring landing operations, William of Orange, decided to visit his uncle, who was so out of place in Ireland. The English army 21 June 1690 was planted in Chester on 300 transports and departed to the shores of the Green Island 24 number, the new English king (he personally commanded the troops) landed in the Belfast area.

The advantage in the forces on the island was transferred to the orangists (that is, supporters of Orange). The transition of the British forces was unobstructed, there was no opposition to them. The news of the landing of William depressingly acted on the Jacobite camp. Ironically, the French fleet's line forces reached an acceptable degree of readiness, and June Tourville left Brest at the head of the ships of the line 23 and 70 firefighters. Despite the fact that the French who had lingered at sea could not prevent the formation of the English and Dutch fleets, the task before the vice-admiral was the same: to cut off William from England, to force the enemy to battle, to clear the English Channel from enemy squadrons for unhindered landing in England .

The English fleet under the command of Admiral Arthur Herbert, who was unaware of the enemy’s withdrawal, joined the Dutch squadron of Cornelis Evertsen off the Isle of Wight. Several allied squadrons were at that time in different regions, and therefore the general forces of the Anglo-Dutch fleet were inferior to the French. They consisted of 57 battleships (English 35 and Dutch 22). The Allies were blissfully ignorant when French scouts were spotted on the Isle of Wight on July 3. The lack of wind prevented Herbert from immediately dropping anchor, and on July 5, the main forces of Turville were clearly visible in the distance. At the military council it was decided not to accept the battle, but to move east - the enemy had an impressive numerical advantage. Herbert was inclined to expectant tactics: to choose the mouth of the Thames as the operational base and to wait for reinforcements from other regions. This decision was reported to London, along the way, aggressively notifying of the need for reinforcements.

A weak wind and good knowledge of the tides in the eastern part of the English Channel allowed the allies to avoid meeting Tourville on their heels. However, the line of reasoning of the higher leadership was quite different from the opinion of the cautious Herbert. 9 July came a very sharp response from Queen Mary, in which the admiral was categorically instructed to give battle to the enemy. In London, for some reason, the combat readiness of the French fleet was considered low, Herbert did not share the caution, promised reinforcements, but demanded decisive action. The royal court needed a victory, because the proximity of the French fleet caused embarrassment to certain categories of the population, and even in Ireland the situation was still unclear. Herbert tried, of course, to correctly object - in the answer he wrote, he pointed to the superiority of the enemy in forces, indicated the advantageousness of the current position. It was then that the phrase “fleet in being” was first uttered, that is, the fleet, which only by its presence is capable of obstructing the plans of the enemy. However, to quash the Queen has always been a matter of insecurity, and the admiral promised, reluctantly, to execute all orders exactly.

Battle at Heady Head

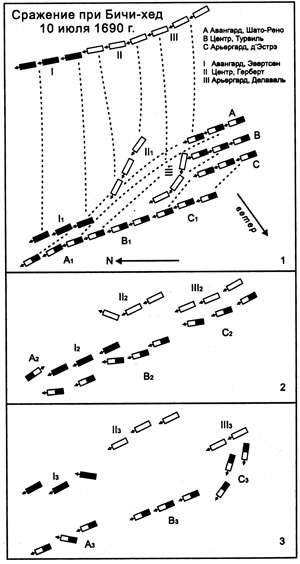

Early in the morning of 10 on July 1690 of the year, with a fresh northeast, the allied fleet took off its anchors and moved to the French waiting for them. Thus began the battle, which entered historylike the battle of Beachy Head. At this point, Turville had 70 battleships, 8 frigates, 18 firefighters. There were a total of 4600 guns and 28 thousands of crew members on the ships. The Vice-Admiral himself commanded the center, holding his flag on the 110-gun "Soleil Royale". Cordebatalia consisted of 28 battleships (six of them had 70 and more guns). The avant-garde under the command of Marquis Chateau-Renault (the flagship of the 100-gun “Dauphin Royal”) consisted of 22 battleships, five of them armed with 70 and more guns. He closed the French rearguard column - 20 of linear (7 large) ships under the command of Count d'Estre (flag on the 84-gun "Grande"). Due to the fact that the fleet was preparing to march in a great hurry, not everything was brought to the proper level. The number of personnel reached almost 4 thousand people, and the powder, which was obtained from the Brest arsenal, turned out to be of low quality and, according to eyewitnesses, was more like charcoal.

The allies, lined up and departed to meet the enemy, looked like this. The lead squadron was a Dutch squadron (22 of the ship of the line) under the command of Cornelis Evertsen (flag on the 74-gun Holland). The center, also a battleship 22, headed Herbert directly at the flagship 100 cannon Royal Sovereign, routed the convoy of the Anglo-Dutch navy rearguard of Vice Admiral Delaval, who was holding the flag at the 90 cannon Coroneyshen. The rearguard counted 13 battleships. Herbert's plan took into account the difference in forces: he expected to engage in battle with the enemy rearguard, and with the rest of the French fleet to conduct a shootout at long range. In this case, it was possible to reduce the battle, in principle unprofitable for the allies, to an intense exchange of fire without serious consequences for the parties. Then it would be possible to calm the queen (they gave a battle), and try to turn the matter to a draw result, and continue to take time.

As the enemy approached, the entire French fleet tacked and lay down on a parallel course. At 9 in the morning Evertsen approached the distance of a cannon shot and soon opened fire. Thorington (the junior flagship of the Allied Cordebtalia), who followed the Dutch, ordered the sails to fly in, reducing the speed of convergence, which was envisaged by the battle plan. The center of the French fleet stretched in the wind, further increasing the distance between Herbert and the Allied vanguard. Around 9.30, Delaval with his 13 battleships actually approached the French avant-garde with a pistol shot and started a fight. The main forces of the Allies continued to stay somewhat apart. The Dutch ships, not slowing down the sail, tried to cover the French avant-garde, but the frequent and accurate fire of the French medium-caliber artillery began to cause great damage. The fact is that the French were of the opinion that it would be more sensible to place less heavy but more rapid-firing guns on battleships of battleships. And now their average (18- and 12-pound) artillery destroyed the crews, crushed the mast and rigging. The sails torn by the nuclei reduced the speed of the Dutch battleships. The French, whose ships were more high-boring, retained their combat capability.

In order to somehow neutralize the enemy’s superiority in artillery, Evertsen ordered to reduce the distance between the matelot for better concentration of fire. However, now the length of the Dutch wake column decreased, and Chateau-Renault began to cover her head. Around the 10 in the morning, the Allied Center opened fire on the main forces of Turville, but did not particularly bold and tried to keep at a certain distance. The gap between the Allied forces between the avant-garde and the center was increasing. The French admiral immediately noticed these flaws in the enemy wake column from the side of his flagship “Soleil Royal”. With the help of flag signals, he gives the order to Chateau-Renault to bypass the Dutch on the windward side in order to put Evertsen in two fires. The command transmission system for flags was well developed in the French fleet, thanks to the numerous exercises and maneuvers that Tourville carried out tirelessly. At about one o'clock in the afternoon the French avant-garde swept the Dutch column. Now the French were able to effectively reach the head of the enemy’s main forces - the Plymouth 58-gun battleship, which was ahead of them, suffered numerous injuries. By twisting his corpsicialist toward the English, Tourville prevented them from giving help to the Dutch.

Evertsen and his subordinates fought bravely and skillfully, but their situation deteriorated with each passing hour. By 3 hours most of the Dutch avant-garde has already been taken by the French in two lights. Having twisted the structure of its central divisions, Turville started a battle with the terminal ships of the Dutch column. Huge "Soleil Royal" fired frequent and accurate fire at the enemy. A flurry of French fire hits Evertsen’s battleships, while Herbert, holding her ships in the wind, barely participates in the battle. In a critical situation, the Dutch admiral, remembering the beginning of his naval career, resorted to the tactics of the Dunkirk privateers: on a signal, not setting sail, he anchors his ships. For the 68-cannon “Friesland”, this turned out to be too late in action - having lost all the anchors and masts, he ndrived to the convoy of the main forces of the French, where the 80-gun “Sovieren” took the helpless Dutchman to board the ship. The Friesland suffered so much from artillery fire that they refused to take the idea of towing it and chose to blow it up, having previously removed the crew. The French did not immediately notice the trick of Evertsen - the smoke from the many hours of cannonade completely closed the visibility. The strong outflow that had begun, dragged the French battleships to the south-west, the Dutch were out of the fire zone. Tourville, who discovered the enemy's maneuver at the very last moment, could no longer influence the course of the battle - the steady calm introduced adjustments to the plans of the French admiral. Unable to cope with a powerful current, the Ocean Fleet, like its opponent, also anchored.

The Dutch got pretty - many hours spent under heavy enemy fire was very expensive. Only three ships of Evertsen could move independently, since they carried at least some sails. The remaining battleships were a very sad sight: many had no masts, holes in the hulls, fires raging on the decks. The loss of personnel, especially those wounded by fragments of a broken mast, was very tangible. The fires on two battleships could not be taken under control - they were left by the crews and subsequently exploded. The Dutch admiral asked for help from his flagship to help carry out towing. But Herbert confined himself to sending a few frigates that the French managed to easily drive off. Late in the evening, somehow correcting the most severe damage, Evertsen is anchored and, with the help of boats, begins towing his mutilated ships to the east, in the direction of the Thames. At 21, a light wind blew out and the English joined the retreat. The French fleet begins pursuit later, taking advantage of the tide.

The retreat of the Allied fleet occurred in complete disarray and disorder. Severely damaged ships shackled Herbert - in the following days, the most damaged four Dutch battleships and one English were set on fire and abandoned. Bravely acted commander Schnellen on his 64-gun "Maz." Seeing that he did not break away from the two large French frigates pursuing him, he went into a small cove - transported ship guns to the coast, using the whole crew, and built a coastal battery in a suitable place. When the pursuers approached the effective shot, they were met with frequent and accurate fire. The French were forced to abandon the prosecution. For this act, the resourceful and courageous captain Schnelllen was subsequently sent to Shautbenahty. Some historians (for example, Mr. Mahan in his "Influence of naval force on history") complain about the insufficiently vigorous persecution that Turville carried out. However, nature came out against the French naval commander - the next few days after the Battle of Beachy Head, the sea was almost completely calm, and the heavier ships of Tourville could not develop enough speed for effective pursuit. The battle of Beachy Head ended with a complete victory for the French. During the battle, three Allied battleships were destroyed, five more were burned during the retreat. Losses in personnel reached more than 3 thousand people. The damage to Tourville was several times lower: 311 killed, more than 800 injured. All ships of the Ocean Fleet retained their combat capability.

Missed Opportunities

18 July utterly worn out allies entered the Thames. Herbert was so afraid that the enemy would follow him, that he ordered all buoys and landmarks to be removed. The tumult in England caused by Beachy Head's defeat was impressive. In London, in the most serious way, they were preparing to repel the French invasion — the militia were arming themselves; the merchants took their goods away from the city. But Tourville still 15 numbers stopped the pursuit and turned back to the west to Torbay, where he made a small landing on the shore, destroying several objects on the shore. The landing corps, which was being formed in Rochefort, was not yet ready, and the admiral himself did not have sufficient forces for a full landing. Nevertheless, for some period of time the French seized the waters of the English Channel. Almost the rest of July, Tourville devastated British and Dutch maritime trade, causing enormous damage to it. Louis XIV did not take a unique chance. 11 July, the day after the Battle of Beachy Head, in Ireland in the area of the River Boyne, Marshal Schomberg defeated the army of Jacob II. Soon the demoralized ex-king again fled to France. The landing of the French troops did not take place, despite the fact that most of the army of William of Orange was in Ireland. Just think, over more than 100 years, the emperor Napoleon dreamed of at least a couple of hours of suitable weather for a landing in England!

Anglo-French naval confrontation continued. There were many battles ahead, glorious victories and bitter defeats. Two proud and ambitious people jealously and watchfully followed one another, holding onto the hilt of the swords, periodically pulling them out of the scabbard. Compromises were considered a manifestation of weakness, the ranting of diplomacy too boring, and then both sides willingly gave the floor to His Majesty Iron.

Information