The mystery of the tapestry from Bayeux (Part of 1)

For the first time about the "tapestry" I learned from the "Children's Encyclopedia" of the Soviet era, in which for some reason it was called ... "The Bayonian Carpet." Later I found out that ham is made in Bayonne, but the Bayeux city is the storage place of this legendary tapestry, which is why it was named this way. Over time, my interest in the “carpet” was only strong, I managed to get a lot of interesting (and unknown in Russia) information on it, well, but in the end it turned into this very article ...

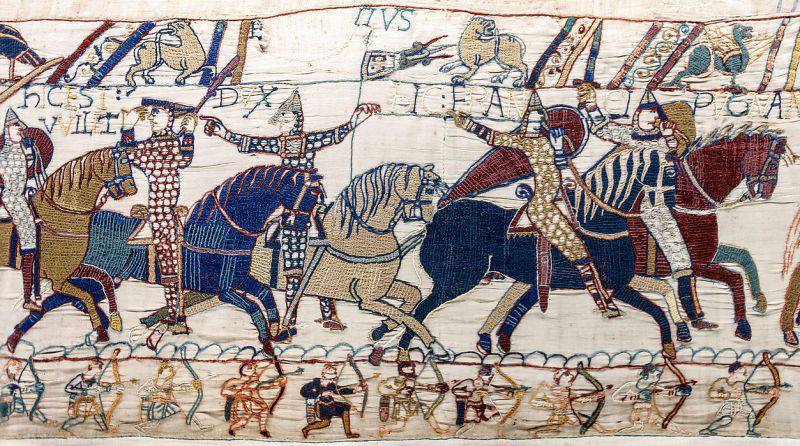

There are not so many battles in the world that have radically changed the history of an entire country. In fact, in the western part of the world there is probably only one of them - this is the battle of Hastings. However, how do we know about her? What general evidence exists that she really was, that this is not fiction of idle chroniclers and not a myth? One of the most valuable evidence is the famous Bayeux Carpet, on which “the hands of Queen Matilda and her maid of honor” - usually written about this in our domestic history books - depicts the Norman conquest of England, and the battle of Hastings itself. But the celebrated masterpiece raises no less questions than answers.

Works of monarchs and monks

The earliest information about the battle of Hastings is not from the British, but not from the Normans. They were recorded in another part of northern France. In those days, modern France was a patchwork quilt from separate senior estates. The power of the king was strong only in his domain, for the rest of the land he was only a nominal ruler. Normandy also enjoyed great autonomy. It was formed in 911, after King Charles Simple (or Rustic, which sounds more correct, and most importantly more worthily), desperate to see the end of the Viking raids, ceded the land near Rouen to the leader of the Vikings Rollo (or Rollo). Duke Wilhelm was born to Rollon with great-great-great-grandson.

By 1066, the Normans extended their authority to the territory from the Cherbourg Peninsula and right up to the mouth of the River Som. By this time, the Normans were real French - they spoke French, adhered to French traditions and religion. But they maintained their sense of separateness and remembered their origin. For their part, the French neighbors of the Normans were afraid of strengthening this duchy, and they did not mix with the northern newcomers. Well, they did not have for this suitable relationship, that's all! To the north and east of Normandy lay the lands of such "non-Normans" as the possession of Count Guy of Poitou and his cousin Count Eustace II of Boloni. In 1050's they both feuded with Normandy and supported the Duke William in his invasion of 1066 only because they pursued their own goals. Therefore, it is particularly noteworthy that the earliest recording of information about the Battle of Hastings was made by a Frenchman (and not a Norman!) Bishop Guy Amiensky, the uncle of Count Guy of Poitou and his cousin of Count Eustace of Bolon.

The work of Bishop Guy is a detailed poem in Latin, and it is entitled The Song of the Battle of Hastings. Although its existence was known for a long time, it was discovered only in 1826, when the archivists of the King of Hanover accidentally stumbled upon two copies of the “Song” of the 12th century. in the royal library of bristol. The Song can be dated 1067, and, at the latest, by the period up to 1074-1075, when Bishop Guy died. It presents the French, rather than the Norman, point of view on the events of 1066. Moreover, unlike the Norman sources, the author of the “Song” makes the hero of the battle of Hastings not William the Conqueror (who still would be better to call Guillaume), but the graph Eustace II of Bologna.

Then the English monk Edmer of Canterbury Abbey wrote "A History of Recent (Recent) Events in England" between 1095 and 1123. "And it turned out that his characterization of the Norman conquest completely contradicts the Norman version of this event, although it was underestimated by historians keen on other sources. In the XII century. There were authors who continued the tradition of Edmer and expressed sympathy for the conquered English, although they justified the victory of the Normans, which led to the growth of spiritual values in the country. Among these authors are the British, such as: John Worchertersky, Wilhelm Molmesbersky, and the Normans: Oderic Vitalis in the first half of the XII century. and in the second half, Jersey-born poet Weiss.

In written sources from the side of the Normans, Duke Wilhelm receives much more attention. One such source is the biography of William the Conqueror, written in 1070's. one of his priests - Wilhelm of the Poitters. His work, The Acts of the Duke Wilhelm, was preserved in an incomplete version printed in the 16th century, and the only known manuscript was burned during the 1731 fire. This is the most detailed description of the events of interest to us, the author of which was well informed about them. And in this capacity the "Acts of the Duke Wilhelm" are invaluable, but not without bias. Wilhelm of Poitters is a patriot of Normandy. At every opportunity, he praises his duke and curses the evil usurper Harold. The goal of labor is to justify the Norman invasion after its completion. Without a doubt, he was embellishing the truth, and even at times he simply deliberately lied to make this conquest just and legal.

Another Norman, Oderik Vitalis, also created a detailed and interesting description of the Norman conquest. However, it was based on written in the XII century. the writings of various authors. Oderick himself was born in 1075 near Shrusberg to an Englishwoman and Norman family and was sent by parents to a Norman monastery in 10 years. Here he spent his whole life as a monk, engaged in exploration and literary creation, and between 1115 and 1141. created the history of the Normans, known as "Church History". The well-preserved copy of this work is in the National Library in Paris. Torn between England, where he spent his childhood, and Normandy, where he lived all his mature life, Oderick justifies the conquest of 1066, which led to religious reform, but does not close its eyes to the cruelty of the newcomers. In his work, he even makes William the Conqueror call himself a “cruel murderer”, and on his deathbed in 1087, he puts a completely uncharacteristic admission into his mouth: “I treated the locals with unjustified cruelty, humiliating the rich and the poor, unfairly depriving them of their own lands; I caused the death of many thousands because of famine and war, especially in Yorkshire. ”

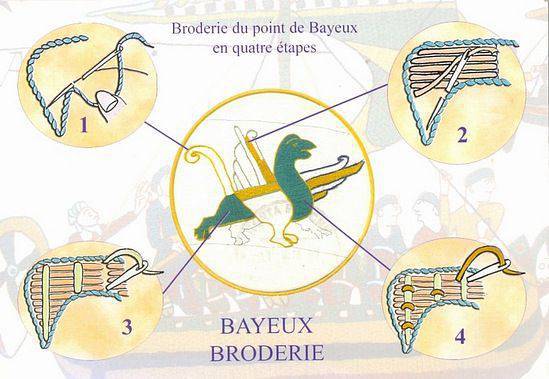

These written sources are the basis for historical research. In them we see an exciting, instructive and mysterious story. But when we close these books and come to the tapestry from Bayeux, we as if from a dark cave fall into a world filled with light and full of bright colors. The figures on the tapestry are not just funny characters of the 11th century embroidered on linen. They seem to us to be real people, although sometimes they are embroidered in a strange, almost grotesque manner. However, even just looking at the "tapestry", after some time you begin to understand that it, this tapestry, hides more than it shows, and that it is still full of secrets that are still waiting for their researcher.

Travel in time and space

How did it happen that a fragile work of art survived much more durable things and survived until now? This in itself is an outstanding event worthy of, at least, a separate story, if not a separate historical study. The first evidence of the existence of a tapestry dates from the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries. In the period between 1099 and 1102. the French poet Bodri, the abbot of the Burzhelsky monastery, composed a poem for the Countess Adele Bloy, daughter of William the Conqueror. The poem describes in detail the magnificent tapestry, located in her bedchamber. According to Beaudry, the tapestry is embroidered with gold, silver and silk, and it depicts the conquest of England by her father. The poet describes in detail the tapestry, scene by scene. But it could not be tapestry from Bayeux. The tapestry, described by Beaudry, is much smaller, created in a different manner and embroidered with more expensive threads. Perhaps this Adele tapestry is a miniature replica of the tapestry from Bayeux, and he did adorn the bed of the Countess, but was then lost. However, most scholars believe that the Adele tapestry is nothing more than an imaginary model of tapestry from Bayeux, which the author saw somewhere before 1102. To prove, they cite his words:

“On this canvas - the ships, the leader, the names of the leaders, if, of course, it ever existed. If you could believe in its existence, you would see in it the truth of history. ”

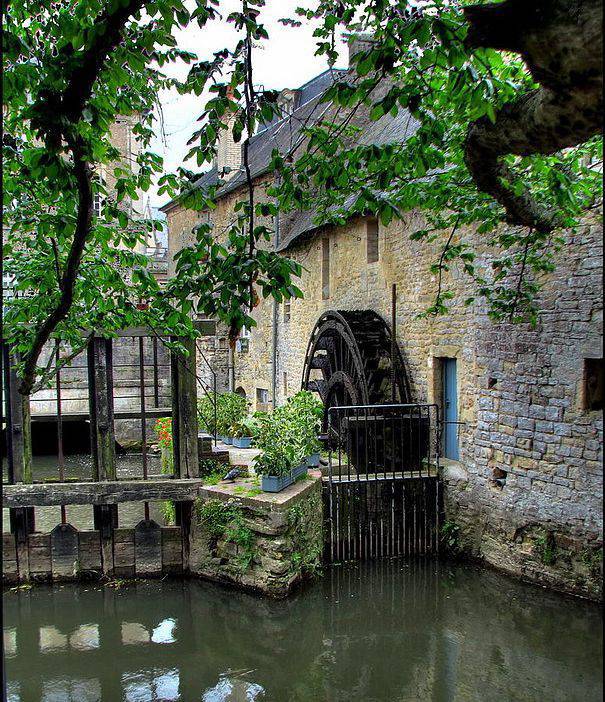

The reflection of the tapestry from Bayeux in the mirror of the poet’s imagination is the only mention of its existence in written sources up to the 15th century. The first authentic mention of the tapestry from Bayeux dates back to 1476. Its exact location also dates back to the same time. The list of 1476 Bayesk Cathedral contains data according to which in the possession of the cathedral there was “a very long and narrow linen canvas, on which were embroidered figures and comments on scenes of the Norman Conquest”. Documents show that every summer the embroidery was hung around the nave of the cathedral for several days during religious holidays.

We probably will never know how this fragile 1070 masterpiece. Reached us through the centuries. For a long period after 1476, there is no information about tapestry. He could easily perish in the crucible of the 16th century religious wars, since in 1562 the Bayesian Cathedral was destroyed by the Huguenots. They destroyed in the cathedral both books and many other items named in the 1476 inventory. Among these things is the gift of William the Conqueror - a gilded crown and at least one very valuable nameless tapestry. The monks knew about the upcoming attack and managed to transfer the most valuable treasures under the patronage of local authorities. Perhaps the tapestry from Bayeux was well hidden or the robbers simply looked at it; but he managed to escape death.

Turbulent times were replaced by peaceful ones, and the tradition to hang out tapestry during the holidays was revived. In place of flying clothes and pointed hats of the 14th century. tight pants and wigs came, but the people of Bayeux still looked at the tapestry depicting the victory of the Normans with admiration. Only in the XVIII century. Scientists have paid attention to it, and from that moment the history of the tapestry from Bayeux is known in the smallest detail, although the chain of events that led to the “opening” of the tapestry is only in general terms.

The story of the "discovery" begins with Nicolas-Joseph Fokolt, the ruler of Normandy from 1689 to 1694. He was a very educated man, and after his death in 1721, the papers that belonged to him were transferred to the library of Paris. Among them were found stylized drawings of the first part of the tapestry from Bayeux. Antiquaries of Paris were intrigued by these mysterious drawings. Their author is unknown, but perhaps they had a daughter Fokolta, famous for its artistic talents. In 1724, researcher Anthony Lancelot (1675 - 1740) drew the attention of the Royal Academy to these drawings. In an academic journal, he reproduced the essay of Fockolt; so for the first time an image of a tapestry from Bayeux appeared in print, but no one yet knew what it really was. Lancelot understood that the drawings depicted an outstanding work of art, but had no idea which one. He could not determine what it was: a bas-relief, a sculptural composition in the church choirs or tombs, a fresco, a mosaic, or a tapestry. He only determined that Fockolt’s work describes only part of a large work, and concluded that “he must have a continuation,” although the researcher could not imagine what it could be in length. The truth about the origin of these drawings was discovered by the Benedict historian Bernard de Montfaucon (1655 - 1741). He was familiar with the work of Lancelot and set himself the task of finding a mysterious masterpiece. In October, 1728 of Montfaucon met with the abbot of St. Vigor at Bayeux. The abbot was a local resident and said that the drawings depict ancient embroidery, which is hung out on Bayesky Cathedral on certain days. So their secret was revealed, and the tapestry became the property of all mankind.

We do not know whether Monfokon saw the tapestry with his own eyes, although it is difficult to imagine that he, having given so much effort to his search, missed such an opportunity. In 1729, he published Fockolt's drawings in the first volume of Monuments of French Monasteries. Then he asked Anthony Benoit, one of the best draftsmen of the time, to copy the rest of the tapestry episodes without any changes. In 1732, Benoit’s drawings appeared in the second volume of Monfocon’s Monuments. Thus, all the episodes depicted on the tapestry were printed. These first images of the tapestry are very important: they indicate the state in which the tapestry was in the first half of the 18th century. By that time, the final episodes of embroidery had already been lost, so the Benoit drawings end on the same fragment that we can see in our day. His commentary says that local tradition attributes the creation of a tapestry to William the Conqueror's wife, Queen Matilde. This is where, consequently, the widely spread myth of the "tapestry of Queen Matilda."

Immediately after these publications, a string of scholars from England stretched to the tapestry. One of the first among them was the antiquarian Andrew Dukarel (1713 - 1785), who saw the tapestry in 1752. Getting to it turned out to be a difficult task. Dukarel heard about Bayesian embroidery and wanted to see her, but when he arrived at Bayeux, the priests of the cathedral completely denied its existence. Perhaps they simply did not want to unfold a tapestry for the occasional traveler. But Dukarel was not going to give up so easily. He said that the tapestry depicts the conquest of England by William the Conqueror and added that every year he was hung in their cathedral. This information returned the memory to the priests. The perseverance of the scientist was rewarded: he was led to a small chapel in the southern part of the cathedral, which was dedicated to the memory of Thomas Beckett. It was here, in the oak box, that the folded Bayesian tapestry was kept. Dukarel became one of the first Englishmen who saw the tapestry after the XI century. Later he wrote about the deep satisfaction that he experienced when he saw this "incredibly valuable" creation; although he lamented about his "barbaric technique of embroidery." However, the location of the tapestry remained a mystery to most scholars, and the great philosopher David Hume confused the situation when he wrote that “this interesting and original monument was recently discovered in Rouen”. But gradually the fame of the tapestry from Bayeux spread on both sides of the Tower. True, he had hard times ahead. He was in excellent condition, passed the dark ages, but now he was on the threshold of the most serious ordeal in his history.

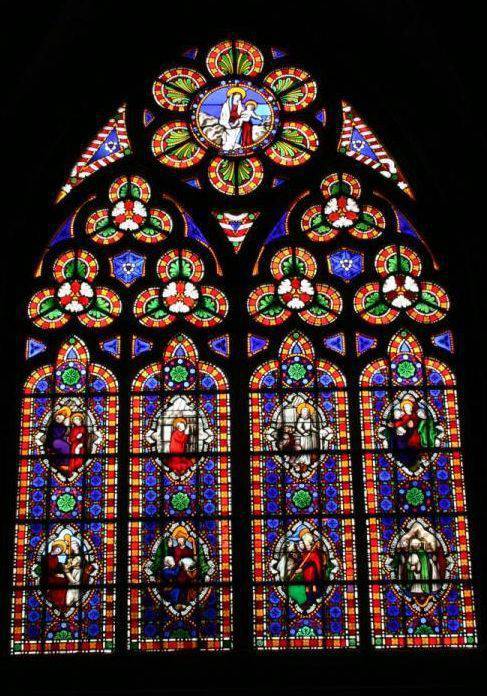

Bastille 14 July 1789 destroyed the monarchy and marked the beginning of the atrocities of the French Revolution. The old world of religion and aristocracy is now completely rejected by the revolutionaries. In 1792, the revolutionary government of France decided that everything related to the history of royal power should be destroyed. In a rush of iconoclasm, buildings collapsed, sculptures crashed, priceless stained glass windows of French cathedrals shattered into smithereens. In the 1793 fire in Paris, 347 volumes and 39 boxes with historical documents burned. Soon the wave of destruction has reached Bayeux.

In 1792, another batch of local citizens went to war in defense of the French Revolution. In a hurry, they forgot the cloth that covered the wagon with equipment. And someone advised to use for this purpose the embroidery of Queen Matilda, which was kept in the cathedral! The local administration gave its consent, and a crowd of soldiers entered the cathedral, seized the tapestry and covered them with a carriage. The local police commissioner, lawyer Lambert Leonard-Leforester, found out about this at the very last moment. Aware of the great historical and artistic value of the tapestry, he immediately ordered his return to his place. Then, having shown genuine fearlessness, he rushed to the cart with the tapestry and personally admonished the crowd of soldiers until they agreed to return the tapestry in exchange for a tarp. However, some revolutionaries continued to harry the idea of destroying the tapestry, and in 1794 they tried to cut it into pieces to decorate a festive raft in honor of the “goddess of Reason”. But by this time he was already in the hands of the local art commission, and she was able to protect the tapestry from destruction.

In the era of the First Empire, the fate of the tapestry was happier. At that time, no one doubted that the Bayesan tapestry was the embroidery of the wife of the victorious conqueror, who wanted to glorify her husband’s achievements. Therefore, there is nothing surprising in the fact that Napoleon Bonaparte saw in him a means to propagate the repetition of the same conquest. In 1803, the then First Consul was planning an invasion of England and, in order to warm up his enthusiasm, he ordered the “tapestry of Queen Matilda” to be exhibited in the Louvre (then called the Napoleon Museum). For centuries, the tapestry was in Bayeux, and the townspeople bitterly parted with a masterpiece that they could never see again. But the local authorities could not disobey the order, and the tapestry was sent to Paris.

The exhibition in Paris was a huge success, the tapestry became a popular subject of discussion in social salons. There was even a play written in which Queen Matilda worked diligently on the tapestry, and a fictional character called Raymond dreamed of becoming a hero soldier to be embroidered on the tapestry too. It is not known whether Napoleon saw this play, but it is claimed that he spent several hours standing in front of the tapestry. Like William the Conqueror, he carefully prepared for the invasion of England. Napoleon's fleet of 2000 ships was located between Brest and Antwerp, and his "great army" of 150-200 thousand soldiers camped in Boloni. The historical parallel became even more obvious when a comet flashed in the sky over northern France and southern England, because on the tapestry from Bayeux, Comet Halley is clearly visible, seen in April 1066. This fact was not ignored, and many considered it to be another omen of defeat. Of England. But, in spite of all the signs, Napoleon was unable to repeat the success of the Norman Duke. His plans did not materialize, and in 1804 the tapestry returned to Bayeux. This time he was in the hands of secular, not church authorities. He never again exhibited at the Bayesky Cathedral.

When peace was established between England and France in 1815, the tapestry from Bayeux ceased to serve as an instrument of propaganda, and was returned to the world of science and art. It was only at this time that people began to realize how close the death of the masterpiece was, and they thought about the place of its storage. Many were worried about how the tapestry was constantly folded and unfolded. This alone hurt him, but the authorities were in no hurry to solve this problem. To preserve the tapestry, the London Society of Antiquaries sent Charles Stozard, an outstanding draftsman, to copy it. For two years, from 1816 to 1818, Mr. Stozard worked on this project. His drawings, along with earlier images, are very important for assessing the then state of the tapestry. But Stozard was not only an artist. He wrote one of the best comments on the tapestry. Moreover, he tried to recover lost episodes on paper. Later, his work helped the restoration of the tapestry. Stozard clearly understood the need for this work. “It will take a few years,” he wrote, “and there will be no opportunity to complete this work.”

But, unfortunately, the final stage of work on the tapestry showed the weakness of human nature. For a long time, being alone with the masterpiece, Stozard succumbed to the temptation and cut off a piece of the upper border (2,5х3 cm) as a keepsake. In December 1816, he secretly brought a souvenir to England, and five years later he died tragically - fell from the forests of Bere Ferrers Church in Devon. The heirs of Stozard handed over a piece of embroidery to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where he exhibited as a "part of the Bayesian tapestry". In 1871, the museum decided to return the “lost” piece to its true place. He was taken to Bayeux, but by that time the tapestry had already been restored. It was decided to leave the fragment in the same glass box in which it arrived from England and place it next to the restored curb. All would be nothing, but not a day went by, so that someone would not ask the keeper about this fragment and the English commentary on it. As a result, the guardian's patience ran out, and a piece of tapestry was removed from the exhibition hall.

There is a story telling that Stozard's wife and her “weak female nature” are to blame for stealing a tapestry fragment. But today nobody doubts that Stozard himself was a thief. And he was not the last one who wanted to grab with him at least a part of an ancient tapestry. One of his followers was Thomas Diblin, who visited the tapestry in 1818. In his book of travel notes, he writes, as if it goes without saying that he had difficulty getting access to the tapestry, he cut off several strips. The fate of these patches is not known. As for the tapestry itself, in 1842 it was transferred to a new building and, finally, placed under glass protection.

The fame of the tapestry from Bayeux continued to grow, thanks in large part to printed reproductions that appeared in the second half of the nineteenth century. But this was not enough for some Elizabeth Wardle. She was the wife of a wealthy silk merchant and decided that England deserved something more tangible and durable than photographs. In the middle of 1880's. Mrs. Wardle gathered a group of like-minded people from 35 people and began to create an exact copy of the tapestry from Bayeux. So, after 800 years, the story of Bayesian embroidery was repeated. It took the Victorian lady two years to complete her work. The result was great and very accurate, similar to the original. However, prim British ladies could not bring themselves to convey some details. When it came to the image of the male genitalia (clearly embroidered on the tapestry), authenticity gave way to modesty. On their copy, the Victorian needlewomen decided to deprive one naked character of his manhood, and prudently dressed the other. But now, on the contrary, the fact that they modestly decided to cover, involuntarily attracts special attention. The copy was completed in 1886 and went on a triumphal exhibition tour in England, then in the USA and Germany. In 1895, this copy was donated to the town of Reading. To this day, the British version of the Bayesian tapestry is in the museum of this English town.

The Franco-Prussian War 1870 - 1871 as well as the First World War, did not leave marks on the tapestry from Bayeux. But during the Second World War, the tapestry survived one of the greatest adventures in its history. 1 September 1939, as soon as German troops invaded Poland, plunging Europe into the darkness of war for five and a half years, the tapestry was carefully removed from the exhibition booth, turned off, sprayed with insecticides, and hidden in a concrete shelter in the foundation of the episcopal palace in Baye. Here the tapestry was kept for a whole year, during which only occasionally it was checked and sprinkled again with insecticides. In June, 1940 France fell. And almost immediately the tapestry came into the view of the occupying authorities. Between September 1940 and June 1941 the tapestry was at least 12 once exhibited by German audiences. Like Napoleon, the Nazis hoped to repeat the success of William the Conqueror. Like Napoleon, they saw the tapestry as a means of propaganda, and, like Napoleon, postponed the invasion of 1940. Churchill's Britain was better prepared for war than Harold's England. Britain won the war in the air and, although it continued to bomb, Hitler sent his main forces against the Soviet Union.

Nevertheless, the interest of Germany to the tapestry from Bayeux was not satisfied. In Anenerbe (ancestral heritage) - the research and education department of the German SS, became interested in tapestry. The purpose of this organization is to find "scientific" evidence of the superiority of the Aryan race. Anenerbe attracted an impressive number of German historians and scholars who readily abandoned their truly scientific career for the sake of the interests of the Nazi ideology. This organization is notorious for its inhuman medical experiments in concentration camps, but it was engaged in archeology and history. Even in the most difficult times, the SS wars spent huge amounts of money on the study of German history and archeology, the occult and the search for works of art of Aryan origin. The tapestry attracted her attention by the fact that it depicted the military prowess of the Nordic peoples - the Normans, the descendants of the Vikings and the Anglo-Saxons, the descendants of the Angles and Saxons. Therefore, the “intellectuals” from the SS developed an ambitious project to study the Bayesian tapestry, in which they intended to photograph and redraw it in full, and then publish the received materials. The French authorities were forced to obey them.

In order to study 1941 in June, the tapestry was transported to the Juan Mondoye Abbey. The research team was led by Dr. Herbert Yankukhn, an archeology professor from Kiel, an active member of Anenerbe. Yankukhn gave a lecture on Bayesian tapestry in Hitler’s “circle of friends” 14 on April 1941 and at the Congress of the German Academy in Stettin in August 1943. After the war, he continued his scientific career and was often published in History of the Middle Ages. Many students and scholars read and cited his work without realizing his dubious past. Over time, Jankuhn became Professor Emeritus of Göttingen. He died in 1990, and his son donated works on Bayesian tapestry to the museum, where they still form an important part of his archive.

Meanwhile, on the advice of the French authorities, the Germans agreed to transport the tapestry to the repository of works of art in the Château de Surche for security purposes. It was a sensible decision, since Chateau, a large palace of the 18th century, was far from the theater of operations. Mayor Bayeux, Senor Dodeman made every effort to find a suitable transport for the transport of the masterpiece. But, unfortunately, he managed to get only a very unreliable, and even dangerous, truck with a gas-powered engine with the power of an entire 10 hp, which worked on coal. A masterpiece, 12 bags of coal, and 19 August 1941 were loaded into it, and the incredible journey of the famous tapestry began.

At first everything was fine. The driver and the two attendants stopped for lunch in the town of Fleurs, but when they got ready to set off again, the engine would not start. After 20 minutes, the driver started the car, and they jumped into it, but then the engine went berserk on the first lift, and they had to get out of the truck and push it uphill. Then the car flew downhill, and they ran after her. This exercise they had to repeat many times, until they overcame more 100 miles separating Bayeux from Sürsch. Reaching the destination, the exhausted heroes did not have time to rest or eat. As soon as they unloaded the tapestry, the car moved back to Bayeux, where it was necessary to be before 10 hours of the evening because of the strict curfew. Although the truck became lighter, it still did not drive uphill. By 9 hours of the evening, they only reached Alancion, a town halfway to Bayeux. The Germans were evacuating the coastal areas, and it was crowded with refugees. In hotels there were no places, in restaurants and cafes - food. Finally, the city administration concierge regretted them and let them into the attic, which also served as a camera for speculators. From food he had eggs and cheese. Only the next day, after four and a half hours, all three returned to Bayeux, but immediately went to the mayor and reported that the tapestry had safely crossed occupied Normandy and was in storage. There he lay still three years.

6 June 1944 Allies landed in Normandy, and it seemed that 1066 events were reflected in the mirror of history with the exact opposite: now a huge fleet with warriors on board crossed the English Channel, but in the opposite direction and with the aim of liberation, not conquest. Despite fierce battles, the Allies struggled to win back the bridgehead for the offensive. Suersche was 100 miles from the coast, but still the German authorities, with the consent of the French Minister of Education, decided to move the tapestry to Paris. It is believed that Heinrich Himmler himself was behind this decision. Of all the priceless works of art stored in the Chateau de Sursch, he chose only tapestry. And 27 June 1944, the tapestry was transported to the cellars of the Louvre.

Ironically, long before the tapestry arrived in Paris, Bayeux was released. 7 June 1944, the day after the landing, the allies from the British Infantry Division 56 took the city. Bayeux became the first French city liberated from the Nazis, and unlike many others, its historic buildings were not affected by the war. In the British military cemetery there is a Latin inscription stating that those who were conquered by William the Conqueror returned to liberate the Conqueror’s homeland. If the tapestry remained in Bayeux, it would have been released much earlier.

By August 1944, the Allies approached the outskirts of Paris. Eisenhower, the commander in chief of the Allied forces, intended to pass by Paris and invade Germany, but the leader of the French Liberation, General de Gaulle, was afraid that Paris would fall into the hands of the Communists, and insisted on the speedy release of the capital. The battles began in the suburbs. From Hitler received an order in the case of leaving the capital of France, wipe it off the face of the earth. To this end, the main buildings and bridges of Paris were mined, and torpedoes of great power were hidden in the subway tunnels. General Holtitz, who commanded the Paris garrison, came from the old family of the Prussian military and could not disrupt the order. However, by that time, he realized that Hitler was crazy, that Germany was losing the war, and in every possible way pulled out time. It was under such and such circumstances that on Monday 21 August 1944, two SS men suddenly entered his office at the Maurice Hotel. The general decided it was him, but he was wrong. The SS men said that they had an order from Hitler to take a tapestry to Berlin. It was possible that he was intended, along with other Nordic relics, to be placed in the quasi-religious sanctuary of the SS elite.

The general from the balcony showed them the Louvre, in the basement of which the tapestry was kept. The famous palace was already in the hands of the French resistance fighters, and machine guns were firing on the street. The SS men thought, and one of them said that the French authorities, most likely, had already taken the tapestry, and there was no point in taking the museum by storm. Thinking a little, they decided to return empty-handed.

Information