Born in the fire of revolution and war

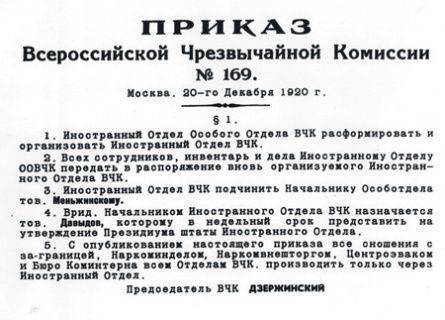

Every year on December 20, the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation celebrates its birthday. On that day back in 1920, Felix Dzerzhinsky signed historical order No. 169 on the creation of the Foreign Department of the Cheka, whose successor today is the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service. The current year for the service is a jubilee. In December, she will celebrate her 95th birthday. In anticipation of this historic event, we would like to offer readers of Independent Military Review a series of essays on the history of the creation and activity of the foreign intelligence of our state.

IN THE BEGINNING OF THE WAY

Foreign intelligence is a necessary part of the state mechanism, solving a whole range of important tasks. Need or not need intelligence - a purely rhetorical question. None of the more or less large, and even more so - a great state can not and can not do without it. This has proven history. This proves and modernity. After all, the main task of foreign intelligence is to obtain for the top leadership of the state reliable, proactive information about the factors that could harm its interests.

It should be emphasized that at any historical stage, under any system, in any circumstances, foreign intelligence protects the security of the state. Over time, the emphasis in its activities may change, some methods of work may be abandoned, but the ruling class will never abandon intelligence as the most important tool of its policy.

Leading American expert and one of the recognized authorities in the field of the history of special services, Jeffrey Talbot Richelson, in his book The History of Spying on the Twentieth Century, in particular, emphasizes:

“The twentieth century witnessed many revolutionary transformations in various fields, but nowhere has this manifested itself so vividly as in intelligence activities.

The transformation of the world in the twentieth century - the complication of the social structure of society, the all-encompassing nature of war, the rapid development of science and technology, the emergence of new states - could not but lead to the transformation of the art of intelligence. The need for information about all aspects of life and activities of foreign powers, including their most advanced weapons, helped turn intelligence into a modern industry that needs both data collection systems created by the latest technology and individuals with extensive knowledge of natural and social sciences.

The October revolution of 1917 marked the beginning of the emergence on the vast territory of the globe of a new independent state - Soviet Russia.

The First World War, the collapse of the monarchy in Russia, the inability of the Provisional Government to keep the situation under control, the transfer of power into the hands of the Soviets caused the old socio-political structures to collapse or be destroyed in the country as a result of the revolutionary process.

From its first steps, the Soviet government was forced to repel the blows of external and internal enemies, to defend the independence and territorial integrity of the new, essentially, state, to bring it out of isolation. To protect national interests, along with other government agencies, new special services were created, including foreign intelligence. In accordance with the Decree of the 20 Council of People’s Commissars of December 1917, the All-Russian Emergency Commission was established under the Council of People’s Commissars for Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (VChK). It was headed by Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky.

Chekists immediately had to face a difficult situation that threatened the existence of Soviet power: the leading world powers - England, France, Italy, Japan and the USA - organized a conspiracy against Soviet Russia, stipulating, in particular, the arrest of the Soviet government and the murder of Vladimir Lenin. The “conspiracy of ambassadors” was successfully eliminated by the Chekists thanks to the energetic measures taken by Dzerzhinsky. This was followed by armed intervention, which the Entente countries launched against their former ally, the Civil War. Soviet Russia was able to withstand these difficult conditions, defeat the interventionists and drive them out of the country, and weaken the internal counter-revolution.

FIRST SCIENTISTS

The origin of Soviet foreign intelligence dates back to 1918, when the Cheka authorities during the Civil War and intervention waged a tense and intense struggle against the numerous enemies of the Soviet state. On the basis of the army emergency commissions and military control bodies, a Special Division of the Cheka was created. His task included the fight against counter-revolution and espionage in the army and on navy, against counterrevolutionary organizations, as well as the organization of undercover work abroad and in areas of the young republic occupied by foreign powers or occupied by whiteguards. Of course, this struggle was mainly of a forceful nature. In the course of it, methods of intelligence activities were also used (undercover penetration into hostile organizations, obtaining information about their plans and personnel).

At the same time, from the very first months of its existence, the VChK attempted to conduct intelligence work behind the cordon. So, in May 1918, the chairman of the Cheka, F. Dzerzhinsky issued an order regulating the activities of the outlaw agents of the Cheka and their interaction with Russian diplomatic missions abroad.

It should be noted here that after October 1917, part of the representatives of the Russian intelligentsia, officers and generals of the old army went over to the side of Soviet power. They helped her re-form an army and navy, make their actions effective and win the first victories. There were such patriots among the royal professional intelligence officers. By putting their specific knowledge at the service of the new government, they contributed to exposing the conspiracies, disclosing the intentions of those who nurtured plans of intervention and occupation of Russian lands.

Here are some examples of such intelligence activities.

Here are some examples of such intelligence activities.At the beginning of 1918, Dzerzhinsky personally recruited Alexey Frolovich, a former banker and publisher of the newspaper Dengi, to work as a secret officer at the Presidium of the Cheka on a patriotic basis. He traveled to Finland several times to collect information about the political situation in the country, plans of the Finnish political circles and the White Guard in relation to Soviet Russia. Filippov succeeded in convincing the command of the Baltic fleet and the Russian garrisons in the Finnish ports to go over to the Soviet side and redeploy to Kronstadt.

In the literature on the history of Soviet foreign intelligence, it is noted that this was the first withdrawal of a Cheka officer for the cordon with intelligence purposes, which marked the beginning of KGB work abroad. This fact was confirmed in the archival materials of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Russia.

In February, a professional diplomat RK was sent to Turkey to organize intelligence work from the territory of this country to Turkey. Sultans. Dzerzhinsky personally instructed him, and also sent a letter to the Soviet authorized representative in Istanbul asking him to provide all possible assistance to the intelligence officer.

The whole long and difficult period of the struggle for the establishment of Soviet power in Siberia and the Far East was occupied with active reconnaissance activities by former tsarist professional intelligence officer staff captain Alexey Nikolaevich Lutsky. He opened in Harbin the plot of General Horvat, chief of the CER and informed the Soviet government in Petrograd about this. Lutsky mined through agents and informed the Center of valuable information about the advance of Japanese troops to Harbin. From February 1920 was a member of the Military Council of Primorye.

On the night of 4 on 5 on April 1920, Japanese soldiers suddenly surrounded all the government offices of Vladivostok and, rushing into the building of the Military Council, arrested the members of the council Sergey Lazo, Vsevolod Simbirtsev and Alexey Lutsky.

For more than a month, they were interrogated and tortured in the dungeons of the Japanese military counterintelligence. Without breaking the will of courageous patriots, the Japanese invaders and the White Cossack Ataman Bochkarev took them out at the end of May from Vladivostok and burned them in the steam-burning furnace at Muraviev-Amurskaya station.

On the instructions of the special departments of the republican Cheka in December 1918, the staff and agents of the Cheka for the reconnaissance and organization of partisan detachments were sent to the rear of the German troops in Ukraine, the Baltic States and Belarus. Intelligence points of the Special Department of the Cheka were also established in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

Of particular danger to the Soviet government were secret counter-revolutionary organizations at home and abroad, most of whom were associated with foreign intelligence services, relied on their help and support, and worked closely with them. It was precisely the interrelation between internal and external threats that forced the Soviet leadership to intensify counter-intelligence and intelligence work of the Cheka.

FOREIGN AND EDUCATIONAL BUREAU

In order to improve intelligence work in April 1920, a special unit was created within the Special Division of the Cheka, the Foreign Information Bureau. When special sections of the fronts, armies and fleets, as well as in some provincial Cheka were foreign offices. They worked in contact with the Registration Directorate of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic, which in those years concentrated military intelligence.

At that time, Soviet Russia had diplomatic relations with Turkey and Germany, and in connection with the signing in 1920 of the treaties on the normalization of relations with the limiting countries (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Finland), diplomatic representations of the RSFSR also opened in the capitals of these countries. In them, with the permission of the Central Committee of the RCP (B.), Residency offices of foreign intelligence were created. Their task was agent penetration into counter-revolutionary White Guard organizations and formations.

At the same time, the VChK leadership developed and enacted an instruction for the Foreign Information Bureau, which stipulated the conditions for the creation and functioning of “legal” residencies in capitalist countries with the aim of “undercovering into explored objects: institutions, parties, organizations”. The instruction provided that in countries that did not have diplomatic relations with the RSFSR, the agency of the bodies of the Cheka should be sent illegally.

The first head of the first full-time foreign intelligence unit of the Special Division of the Cheka was Ludwig Frantsevich Skuiskumbre.

He was born in 1898 in Riga in a Latvian bourgeois family. His father was a store clerk. Ludwig received a secondary education. Fluent in German.

From November 1917, Skeiskumbre worked in economic positions in the administrative department of the Moscow City Council. Member of the PSC (B) since June 1918. In October 1918 of the year volunteered for the 1 Revolutionary Army of the Eastern (later Turkestan) Front. He served as a political worker, then secretary to the chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council, and from the middle of 1919 onwards, as a member of the special department of the army.

At the beginning of 1920, Skoukumbre was transferred to Moscow to the Special Department of the Cheka and in April of the same year he headed the Foreign Bureau of the central apparatus of military counterintelligence.

Later, after the creation of the Foreign Department of the Cheka, Skuiskumbre for some time served as the head of the Investigation Unit (intelligence department) of the Special Department of the Cheka, and soon was appointed deputy head of the Investigative Unit of the INO Cheka.

In 1922, he performed special tasks abroad in the line of INO Cheka. At the beginning of 1923, he went to work in military counterintelligence, and then until 1937, he worked in the Economic Directorate of the OGPU – NKVD.

He was awarded the badge "Honorary Worker of the Cheka-GPU" and a personalized Mauser.

In 1938, he retired for health reasons.

Russian-Polish War

Thus, the Soviet foreign intelligence service, created in the depths of the Special Department of the Cheka, had no independent status until December 1920 and operated within the structures of the army counterintelligence.

What happened in 1920 year? It was the year of the end of the Civil War in the European territory of Russia. In the Far East, fighting continued for another two long years. The Civil War ended with the complete victory of the Red Army.

But in the same time frame of the Civil War, there were “local” wars against the interventionists — the Entente countries and some other states. Among them, the Russian-Polish 1920 war of the year should be distinguished by the scale of military operations and the consequences for the Soviet state.

First, it was a war of opportunity missed for Soviet Russia and its Armed Forces. Secondly, it was the only war that the Red Army had lost in its entire history.

The Entente countries began to prepare the army of the pan-Polish Poland at the end of 1919 of the year. The Poles then received from France alone almost 1,5 thousand guns, about 3 thousand machine guns, over 300 thousand rifles, 0,5 billion cartridges, 200 armored cars, 300 aircraft, a lot of other military equipment.

By the spring of 1920, the Polish army, fully equipped and trained, numbered about 750 thousand soldiers. The 70-thousandth army of General Haller, made up of immigrant Poles living in this country, was transferred from France to Poland from Poland.

Unfortunately, the Russian foreign intelligence service, which was part of the military counterintelligence of the Cheka, which operated in the front line and did not have its residency in European capitals, looked at the military preparations of Poland and the Entente countries. 25 April 1920, the army of Pansky Poland, taking advantage of the fact that the main forces of the Red Army were engaged in the struggle against the Volunteer Army, in particular with the troops of Baron Wrangel entrenched in the Crimea, struck the young republic in the back, going over to the offensive.

The Red Army troops that opposed them, which were part of the Western and South-Western fronts, numbered only about 65 thousand fighters.

The fighting began for the Poles successfully: in the very first weeks of the offensive, they captured Zhytomyr, Korosten, in May they took Kiev and went to the left bank of the Dnieper.

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee, Council of People's Commissars and the Central Committee of the RCP (B.) Declared urgent mobilization of the Communists and Komsomol members into the army. About 1 million people fell under the gun. Thanks to the measures taken in the war, a turning point came: the regiments of the Red Army began to liberate the territories of Ukraine and Belarus captured by the Poles.

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee, Council of People's Commissars and the Central Committee of the RCP (B.) Declared urgent mobilization of the Communists and Komsomol members into the army. About 1 million people fell under the gun. Thanks to the measures taken in the war, a turning point came: the regiments of the Red Army began to liberate the territories of Ukraine and Belarus captured by the Poles.The Entente countries and the USA demanded that the RSFSR government stop the offensive. England sent a note to the Soviet government in which it offered to immediately conclude an armistice with Poland along the “Curzon Line” (at that time the British Foreign Secretary), which was roughly in line with the present western borders of Ukraine and Belarus.

On July 17, the Soviet government rejected Curzon’s ultimatum, but declared its readiness to start armistice negotiations with Poland. At the same time, Trotsky ordered the Western Front to take over Warsaw no later than August 12.

It was then that the commander of the Western Front, Mikhail Tukhachevsky, gave the famous order No. 1423:

“Fighters of the workers' revolution! Fix your eyes on the West. In the West, decide the fate of the world revolution. Through the corpse of white Poland lies the path to a global fire. On bayonets we will carry happiness and peace to working mankind! To the west! To Vilna, Minsk, Warsaw - march! ”

By August 13 the Red Army was in 12 km from Warsaw. However, the Poles managed to intercept and decipher Tukhachevsky's correspondence with Budyonny, which stated that the army was left without ammunition, ammunition and fodder.

French advisers in the army of Pilsudski, General Weygand Marshal Foch, recommended the Poles to take advantage of the situation. 16 August, the Polish army launched a counteroffensive ...

The war turned into a heavy defeat for the troops of the Soviet Republic. The Red Army lost 150 thousand killed. 66 thousand of its fighters fell into Polish captivity, and in the future almost all were killed. Thousands of 30 Red Army soldiers were interned in East Prussia.

October 12 The Russian-Polish armistice negotiations began in Riga on 1920, which resulted in the signing of a peace treaty that was extremely unprofitable for Soviet Russia. Russia lost more than 52 thousand square meters. km of territory east of the “Curzon Line”, and also recognized the independence of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, which they proclaimed under German occupation.

REORGANIZATION OF EXTERNAL EXPLORATION

The war with Poland, a complex set of relations with Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Finland very sharply raised the question of the need for a more complete and high-quality support of the country's leadership with intelligence information.

In September 1920 of the year, having considered at its meeting the reasons for the defeat in the Polish campaign, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the RCP (B) decided on a radical reorganization of foreign intelligence. In particular, it stated:

“The weakest point of our military apparatus is, of course, the staging of undercover work, which was especially clearly revealed during the Polish campaign. We went to Warsaw blindly and suffered a catastrophe.

Considering the current international situation in which we find ourselves, it is necessary to raise the question of our intelligence to the proper height. Only serious, well-placed intelligence will save us from random moves blindly. ”

For the development of documents related to the creation of an independent intelligence unit, a commission was created, which included, in particular, Joseph Stalin, Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov, and Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky.

In accordance with the decision of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the RCP (B.) And the materials of the commission, the chairman of the Cheka, F. Ye. Dzerzhinsky issued on December 20 of 1920 an order No. 169 on the organization of the Foreign Department (INO) of the Cheka, as an independent intelligence unit. The INO staff was 70 people.

This order was an administrative-legal act that formalized the creation of Soviet foreign intelligence, the successor of which today is the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation.

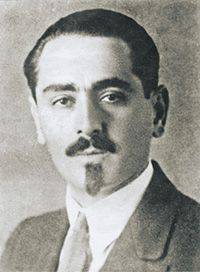

Yakov Khristoforovich Davtyan, professional revolutionary and diplomat, responsible officer of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, was appointed acting head of the Foreign Department of the Cheka. In order to conspiracy, he led the intelligence under the name Davydov.

Creating the foreign intelligence of the young Soviet state, Dzerzhinsky, of course, could not rely only on pre-revolutionary cadres, since it was a question of political intelligence of state security organs. However, since the middle of the 1920-s, “pre-revolutionary specialists,” especially experts in oriental languages, master of perusal and making cover documents, have become increasingly involved in the work of foreign intelligence agencies Cheka.

Following Davydov-Davtyan, the Foreign Division of the Cheka was headed by Solomon G. Mogilevsky, who was the head of foreign intelligence from August 1921 to March 1922. Then he led the Chekists of Transcaucasia.

Among the first heads of intelligence agencies of state security, a high-class professional can rightly be called Mikhail Abramovich Trilisser. In this position, he worked from March 1922-th to October 1929, which at that time was a kind of record. Under him, foreign intelligence was further developed and achieved impressive results in its activities. On Trilisser’s recommendation, such later scouts as Vladimir Vladimirovich Bustrem, who had served time with him under the tsarist regime in the Yaroslavl penal servitude prison, and Dmitry Georgievich Fedichkin, whom Trilisser knew from work in the Far East, came to the Foreign Department.

6 February 1922, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the RSFSR abolished the Cheka and formed the State Political Administration (GPU) of the NKVD of the RSFSR. Foreign Intelligence (INO) became part of the GPU. In connection with the formation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (30 in December 1922), the United State Political Administration (OGPU) under the SNK of the USSR was created by the decree of the Central Election Commission of the USSR 2 in November 1923 of the USSR, which included the Foreign Office (staff: 122 person in the central office and 62 - Abroad).

The creation of an independent foreign policy intelligence accounted for the period of the formation of Soviet power, and, consequently, its history is organically linked with all stages of the development of the Soviet state.

Thus, in the first years of its existence, foreign intelligence efforts were aimed primarily at fighting white emigration abroad, which posed a great danger to Soviet Russia as the basis for the preparation of counter-revolutionary groups. Of great importance was also the obtaining of information about plans for the subversive activities of foreign states against our country.

For three or four years since its inception, the Foreign Department managed to organize "legal" residencies in the countries adjacent to the USSR, as well as in the main capitalist states of Europe - England, France and Germany. A start was made to conduct intelligence from illegal positions, a solid network of agents was formed in white immigrant circles and important government agencies of several countries. Foreign intelligence has begun to acquire scientific and technical information necessary for the needs of the defense and national economy of the USSR.

We will describe the specific work of the foreign intelligence services of the state security bodies at the end of the 1920s - the beginning of the 1930s in further publications.

Information