Wars for Faith and the Peace of Westphalia: Lessons for Eurasia

In the post-Soviet space, the war is not between nations, but between religious parties: Eurasian "Catholics" and "Protestants" - as in the 16th — 18th centuries in Europe

New and old Europe

National states united in the European Union, freedom of religion, separation of religion from the state - this is how we know modern Europe. The immediate prerequisites of its present state, born in modern times, are also known: bourgeois revolutions, the establishment of republics, the declaration of sovereign nations in the person of their “third estate”.

However, we must understand that all this also appeared not from scratch. There was a time when Western Europe was a single space: with one religion, one church, and one empire. Therefore, before the centralized states of the late Middle Ages, as a result of bourgeois revolutions, modern nation-states could emerge, sovereign countries should stand out from a homogeneous imperial space, and the Catholic Church should lose the monopoly on Christianity that it had in the empire.

These processes took place in Western Europe in the 16th — 17th centuries.

What, in fact, was the old Europe before all these events?

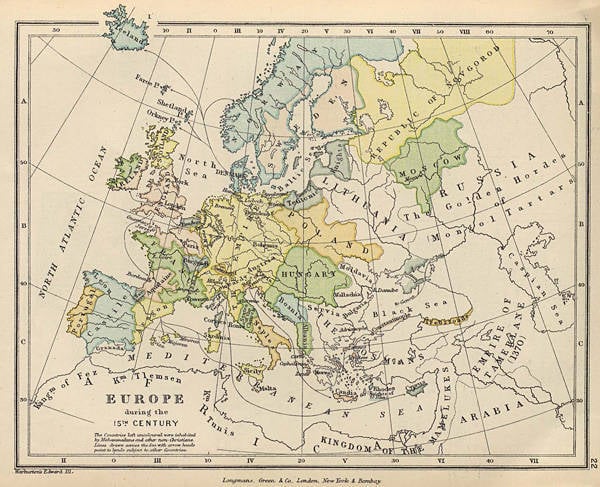

First of all, it was an empire with one church - the Catholic. First, the Frankish Empire, which lasted from the 5th to the 9th century and broke up into three kingdoms in 843. Further, from the Frankish space in the West as a result of the Hundred Years War (1337 — 1453), which was preceded by the defeat of the transnational Templar Order (1307 — 1314) by French King Philip the Fair, the independent England and France stand out. In the east of this space, in 962, a new empire emerges - the Holy Roman Empire, which will formally exist right up to the 1806 year.

The Holy Roman Empire is also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation, which it began to be called from 1512 year. The then “German nation” is far from synonymous with the current German, neither geographically nor by ethnic composition. In general, it should be understood that in addition to the peoples of Central Europe, not only the Anglo-Saxons, but also the founders of France, the Franks, and the founders of Spain, were Visigoths to the German language family. However, later, when all these countries became politically isolated, the territorial array of the German-speaking lands of modern Holland, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Bohemia became the Holy Roman Empire. The latter was a country split between the German-speaking nobility and the Slavic-speaking population, as, indeed, it was in many countries with the aristocracy of Germanic origin.

Against the background of the isolated states of France, England and Spain, of which the colonial empires were born over time, the Holy Roman Empire remained the conservative pole of Europe. As in the Frankish Empire, there were one emperor and one church standing over a multitude of territorial and class formations in it. Therefore, a new Europe, the one we know it in the foreseeable period of its storiesIt is impossible to imagine without the transformation of this particular imperial Catholic space.

Reformation and the world of Augsburg

The first step in this direction was the religious reformation (hereinafter - the Reformation). Let's take out the dogmatic aspects of this process - in this case we are not interested in pure theology, but in political theology, that is, the relationship between religion and government and its role in society.

From this point of view, in the Reformation that began in Western Europe in the XVI century (we wrote earlier that at about the same time such an attempt took place in Russia) two directions can be distinguished. One of them is the Reformation from above, which started from England (1534) and subsequently won in all overseas Northern European countries. Its essence was to remove the ecclesiastical dioceses of these countries from subjection to Rome, to reassign them to the kings of these countries and thus create national state churches. This process was an essential part of separating these countries from a single imperial space into independent nation-states. So, the same England, beginning with the Hundred Years War, was in the vanguard of these processes, it is not surprising that in the religious sense they took place decisively and with lightning speed.

But in continental Europe, the Reformation was different. It was not driven by the rulers of centralized states, which in most cases were not, but by charismatic religious leaders relying on the communities of their co-religionists. In the German lands, the pioneer of these processes was, of course, Martin Luther, who publicly nailed his “1517 theses” to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church in 95 and laid the foundation for his and his supporters confrontation with Rome.

After about twenty years, young Jean Calvin will follow in his footsteps. It is very interesting that, being a Frenchman, he began his activities in Paris, but neither he nor his supporters could gain a foothold there. In general, let us remember this circumstance - the religious reformation in France was not crowned with success, which was clearly confirmed by the St. Bartholomew night - the massacre of French Protestants 24 in August 1572. The Protestants in France did not become the ruling force, as in England, not one of the recognized, as later in the German lands, but the result was that when the Reformation in France did win in the XVIII century, it was no longer a religious, but an anti-religious. character In the 16th century, however, French Protestants eventually had to settle in Switzerland, a country with a Germanic language core and with the inclusion of French and Italian-speaking communities.

This is not surprising - unlike Northern Europe, where the Reformation was relatively quiet from above, or the Romanesque countries, where it failed, a variety of Christian religious movements flourished in the German world at that moment. In addition to the moderate Lutherans, they were both Anabaptists and supporters of Thomas Müntzer, distinguished by social radicalism, and the numerous supporters of the Czech reformer Jan Hus. The last two movements became the leading forces of the Peasant War of 1524 — 1526, which, as its name implies, was of an estate character. But the general political demand for all Protestantism was, however banal it may sound, freedom of religion. New religious communities, denying the authority of Rome, demanded, firstly, their recognition and non-persecution, and secondly, the freedom to spread their ideas, that is, the freedom of Christians to choose their own community and church.

From this point of view, following the results of the Schmalkalden war between the Catholic emperor Charles V and the German Protestants, the Augsburg Peace (1555) became a partial compromise, as it provided for the principle of limited tolerance cujus regio, ejus religio - “whose power, religion and that”. In other words, they could choose faith now, but only princes, subjects were obliged to follow the religion of their overlord, at least publicly.

Thirty Years' War and the Netherlands Revolution

In historiography, as a rule, the Thirty Years War (1618 — 1648) and the Netherlands Revolution (1572 — 1648) are considered separately, but, in my opinion, they are part of a single process. By and large, the Great Civil War in the Holy Roman Empire can be counted from the Schmalkalden War, which began in the 1546 year. The Peace of Augsburg was only a tactical truce that did not prevent the same war from continuing in neighboring Holland in 1572, and in 1618, it resumed in the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, ending with the signing of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

What allows this to assert? First of all, the fact that both the Thirty Years' and the Netherlands War had the same participant on one side - the Hapsburg dynasty. Today, the Habsburgs are associated by many with Austria, but in reality this identification was the result of the Great Civil War. At the time of the end of the XVI - beginning of the XVII century, the Habsburgs were a transnational Catholic dynasty, ruling not only in the Holy Roman Empire, which the Austrian empire itself later proclaimed itself to, but also in Spain, Portugal, Holland and southern Italy. In fact, it was the Habsburgs who at that time inherited and personified the traditional principle of imperial Catholic unity across non-significant political borders.

What was the problem and what was the main reason for the antagonism in Europe? Habsburg fanatical commitment to the Catholic Church and the desire to establish its monopoly everywhere. It was precisely anti-Protestant repression that became one of the main factors that provoked the Dutch uprising against the power of Hapsburg Spain. They also gained momentum in the root of the German lands, despite the formally operating Augburg world. The result of this policy was the creation of a coalition of Protestant princes - the Evangelical Union (1608), and then in response to it and the Catholic League (1609).

The trigger for the start of the Thirty Years War itself, as was the case with the disengagement of England and France, was the formal question of succession to the throne. In 1617, the Catholics succeeded in pushing the pupil of the Jesuits Ferdinand of Styria as the future king of the Protestant Czech Republic, which exploded this part of the Holy Roman Empire. It became a kind of detonator, and the sleeping contradictions between Catholics and Protestants everywhere turned into a war - one of the bloodiest and most devastating in the history of Europe.

Again, it is unlikely that all of its participants were so well versed in theological nuances that they gave their lives for them. It is a question of political theology, it was a struggle of various models of the relationship of religion with government and society. Catholics fought for the empire of one church over the ephemeral state borders, and the Protestants ... this is somewhat more difficult.

The fact is that unlike Catholics, monolithic both in the religious (Rome) and political (Habsburgs) respect, the Protestants were not so integral. They did not have a single political center, they consisted of a multitude of rumors and communities, which are sometimes in very difficult relations between themselves. What they had in common was that they opposed the old order, protested against it, hence this conditional name for this conglomerate of different groups.

Both Catholics and Protestants supported each other across territorial and national borders. And not just ethnic (Germans - Slavs), but national ones (Austrian Protestants together with Czech against Austrian Catholics). Moreover, it can be argued that the nations just emerged from this war on the basis of the disengagement of the parties. An important factor was the impact on the conflict of external parties: France, Sweden, Russia, England, Denmark. Despite the differences, they all, as a rule, somehow helped the Protestants, being interested in the elimination of the continental Catholic empire.

The war was fought with varying success, consisted of several stages, was accompanied by the conclusion of a series of settlements of the peace agreements, which each time ended with its renewal. Until finally the Treaty of Westphalia was concluded in Osnabruck, which was later supplemented by an agreement on ending the Spanish-Dutch War.

What is it over? Its parties had their territorial losses and acquisitions, but very few people remember them today, while the concept “Westphalian system” entered into a steady turn to define new realities established in Europe.

The Holy Roman Empire, and before that not distinguished by particular centralism, has now become a purely nominal union of dozens of independent German states. They were either Protestant or recognized the Protestant minority, but the Austrian empire, whose rulers of the Habsburgs considered themselves to continue the work of the former Holy Roman Church, now became the stronghold of Catholicism in German lands. Spain fell into decay, Holland finally became independent, and with the direct support of France, which thus preferred its pragmatic interests to Catholic solidarity.

Thus, it can be argued that the religious war in Europe ended with the disengagement into territorial states with a predominance of Protestants and Catholics followed by political (but not yet religious) secularization of the latter, as it was in France. Freed from its Protestants, France helps the Protestant Holland and recognizes the Protestant German states, as well as Switzerland.

The imperial unity of Western Europe, which arose during the time of the Frankish empire, partially preserved in the Holy Roman Empire, supported by emperors and popes, is finally a thing of the past. He is being replaced by completely independent states, either with their own churches, or with purely formal domination of Catholicism, which no longer determines the policy of the state and its relations with its neighbors. This was the culmination of the process of creating Europe of nations, which began with the defeat of the Knights Templar and the Hundred Years War and finally completed the formation of the post-war Wilsonian system, the disintegration of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia.

Russia and Westphal: a view from the outside and inside

What relation can all the described events have to Russia and the post-Soviet space? In the author's opinion, today we are seeing exactly their counterpart in the territory of Central Eurasia.

Whether Russia is part of Europe culturally is a question beyond the scope of this study. Politically, Russia, at least until 1917, was part of the European Westphalian system. Moreover, as already indicated, Russia, along with a number of other powers external to the participants in the Thirty Years War, actually stood at its source.

But not everything is so simple. Participation in the same Westphalian system did not prevent the colonial empires of Spain, France, Holland, and Britain from disintegrating. Of all the powers of the Old World, only Russia has not only retained the imperial territorial structure, but also clearly seeks to restore it to the same extent within the framework of the projects of the Eurasian Union and the Russian World.

Can this be understood in such a way that Russia is a European empire that does not want to come to terms with the loss of its colonies, and after deducting this, it is a completely organic part of the European Westphalian system?

The problem is that, unlike Western Europe, Russia was not formed in the area of the first Frankish, and then the Holy Roman Empire. The source of its statehood is Muscovy, and it, in turn, has developed in the space formed after the collapse of Kievan Rus, with the participation of the Horde, the Russian principalities, Lithuania and the Crimea. Subsequently, as the Horde disintegrated, independent khanates were distinguished from it: Kazan, Astrakhan, Kasimov, and Siberian.

That is, we are talking about a special historical and political space, which correlates with the Frankish and Holy Roman empires only externally, but inside it represents another reality. If we look at this reality in a historical perspective, we will see that this space is geopolitically shaped at about the same time as Western European, but ... along the directly opposite trajectory of development.

In Western Europe, at this time, independent states are being formed on the basis of various communities. On the eastern flank of Eastern Europe or in Northern Eurasia, by the time the Horde collapsed, the same thing happens first. Here we see a Catholic-pagan Lithuania, we see Orthodox Muscovy, plowing Northeastern Russia into a fist, we see the Novgorod and Pskov republics pregnant with the Reformation, we see a conglomerate of the Turkic-Muslim khanates, with which all these states were associated with vassal relations. The collapse of the Horde for this space could be the same as the collapse of the old Holy Roman Empire for Central and Western Europe - the birth of a new order of many national states. But instead, something else happens - their inclusion in the new empire, and even more centralized than the Horde.

1471 — 1570 years — destruction of the Novgorod and Pskov Republics, 1552 year — destruction of the Kazan Khanate, 1582 — 1607 years — conquest of the Siberian Khanate, 1681 year — liquidation of the Kasimov Khanate. The Crimean Khanate was liquidated after a large interval in 1783, almost at the same time, the Zaporizhzhya Sich (1775) was finally eliminated. Then they happen: in the 1802 year - the liquidation of the Georgian (Kartli-Kakhetian) kingdom, the 1832 year - the elimination of the autonomy of the Kingdom of Poland, the 1899 year - the actual province of Finland.

Both geopolitically and geo-culturally Central Eurasian space is developing in the opposite direction of Western Europe: instead of manifestation of diversity and creation on this basis of various states, unification and homogenization of space. Thus, being one of the Westphal guarantors for Europe, in relation to its space, Russia emerges and develops on completely anti-Westphalian principles.

How organic was it for this special, huge space? In my article on the “Russian Planet”, I wrote that the Bolsheviks reassembled the territories of the former Russian Empire on the principles of the union of national republics was the result of not some of their insidious Russophobia, as is commonly believed in our day, but nationally and objectively standing in the Empire a question. In fact, the Bolsheviks took the first step towards the Eurasian Westphal. True, it quickly became clear that this was a purely symbolic step - the self-determination of the peoples in the USSR existed only on paper, like other democratic rights guaranteed by the Soviet constitutions. The empire was re-created in an even more monolithic form - thanks to the fact that millions of foreigners were attached to it not purely formally, as in tsarist Russia, but through powerful supranational religion - communism.

In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed, as the Orthodox Russian Empire collapsed before it. They were replaced by new national states that possessed not only legal sovereignty and attributes of statehood, but also their own understanding of the history of the two previous empires, Russian and Soviet. In the nineties, it seemed that Russians were also trying to critically rethink their imperial history. However, twenty years have passed, and not from marginal "red-brown" politicians, but from the top state officials say that the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century, that New Russia was never Ukraine, the phrase "historical Russia " etc.

Is this a manifestation of national revanchism? But what? By the example of the same Ukraine, it can be seen that people with Ukrainian surnames can fight on the side of the pro-Russian forces, just like Russian and Russian-speaking people are fighting for a united Ukraine. Someone thinks that labels like “quilted jackets” and “Colorado” on the one hand, and “Banderlog” on the other, are euphemisms for designating hostile nationalities: Russian and Ukrainian, respectively. But what to do with the fact that their “Colorado” is not only among the non-Russian peoples of Russia, but also in considerable numbers among the Kazakhs, Moldovans, Georgians, and even the Balts? Or with the Russian "banderlog" - young people who in Russia go to rallies with the slogan "Glory to Ukraine - heroes of glory!", And then travels to Ukraine to ask for political asylum and fight in the volunteer battalions?

Westphal for Eurasia

It seems that in Ukraine today there are the first flashes of the “Thirty Years War” for Central Eurasia, which has been pregnant with Westphal more than once, but each time it ended with either an abortion or a miscarriage.

Russia was not a national state - according to its logic, Muscovy took shape, while it was the business of the Russian princes, expanding their inheritance in the shadow of the decrepit Horde. At that moment, she was one of many countries in the series of Lithuania, Novgorod, and nations, because they will take shape only after it, and between religious parties - Eurasian “Catholics” and “Protestants”.

“Catholics” are supporters of sacred imperial unity across national borders, united by single symbols (St. George ribbon), shrines (May 9) and their Rome - Moscow. Undoubtedly, it is the Russians in the ethnic or linguistic sense that are the basis of this community, but being religious in nature, it is fundamentally supranational. In the case of Central-Western Europe, it was Roman-German - Roman in its idea and religion, German in its pivotal element. Moreover, as the territories are exfoliated from this empire, it already officially becomes the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. In central Eurasia, this community is Soviet-Russian - Soviet in its idea, attracting people of numerous nationalities, Russian - in the prevailing language and culture.

Nevertheless, as not all Germans were Catholic, so not all Russians are their analogue today. As already mentioned, Protestants in Europe were a conglomerate of various communities, churches, and future nations. But, despite all these differences, solidarity across national borders was also characteristic of them - for example, Austrian Protestants actively supported the Czechs, were their “fifth column” inside Catholic Austria. Equally, the "Protestant" political denominations and emerging nations such as "Bandera" or the Balts have their own brethren among Russian "Protestants" - their "fifth column" within the "Soviet empire of the Russian nation."

Of course, such comparisons may, at first glance, seem like a stretch: which Catholics, which Protestants in central Eurasia, where they never existed? However, turning to such a methodology of thinking as political theology will allow us to look at this problem more seriously and not dismiss obvious parallels.

After all, the fact that communism possessed all the signs of a secular religion, a political religion was not something obvious, but banal for a long time. In this case, it becomes clear that not only Sovietism, but also anti-Sovietism are nowadays the two political religions of central Eurasia. No less obvious is the fact that communism is not a dogmatic abstraction: of course, Marxism was its “spiritual” (ideological) source, but it was formed and became a reality in a particular historical and cultural environment. In fact, it became a modernized, that is, adapted to the needs of mass society, a variant of Russian imperial messianism, thanks to which it continued its existence and entered a new stage of its development.

In 1918, the Russian Empire fell apart in the same way as the other two similar empires of the Old World: the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman. They took it for granted, and in their place many national states emerged, among which the metropolises themselves were Austria and Turkey. In Russia, the collapse of the empire was also accompanied by war and colossal sacrifices, but the output at the exit was completely different - the restoration of the empire based on modernized secular religion.

It is amazing that today there is an attempt to resurrect the “flesh” of this religion (symbols, rituals, loyalty), from which its “soul” - Marxism-Leninism — has long since flown away. If we proceed from the assumption that the very teaching of the latter was eventually put at the service of the modernized empire, we will have to admit that it is she who is the source of all these bizarre teleportations.

But if Russia is not in its essence a national or multinational state, but a space organized into a sacred empire, it is logical to assume that it cannot avoid its Westphalian reformation, through which its western neighbor has long passed. What could be its trajectory? If we start from European analogies, we can distinguish the following main stages:

- From the Reformation to the Peace of Augsburg - this period we have already passed and the events from Perestroika to the collapse of the USSR and the formation of the CIS, as well as the signing of the Federal Treaty in Russia, correspond to it.

- The expansionism of the Habsburgs, the Netherlands Revolution and the Thirty Years War - the formal Augsburg world consolidated on paper the principle “cujus regio, ejus religio”, but it turned out that the Hapsburgs with their imperial ambitions are not going to take it seriously. The war begins, which is being waged, on the one hand, for preserving and recreating the empire of one religion (ideology, in our case - the political religion), on the other hand, for separating it from it and expelling it from the separated territories. This is the period that we entered now.

- The Peace of Westphalia is a complete de facto emancipation of the Protestant states that survived the war from the old empire, recognition of the Protestant minorities in the regional German Catholic states, the transformation of the Holy Roman Empire into a purely nominal one - a confederation of Protestant and regional Catholic states. At the same time, the formation of a new Catholic empire on the basis of the Austrian empire, which considers itself the successor of the former, but no longer claims to the subordination of Protestant and semi-Protestant states. As applied to our situation, we can talk about the territorial regrouping of the empire with a shift to the east with the final emancipation from it of the "Protestant" and semi-Protestant spaces lying to the West. That is, we are talking about the final collapse of the Soviet imperial space, despite the fact that some state can inherit the Soviet idea as its own, without pretending to be free from the state.

- Secularization of Catholic countries - the subordination of religion to pragmatic state interests in large Catholic countries, republican revolutions, secularization. This stage is most likely for post-Soviet countries like Belarus and Kazakhstan, which will formally remain “Catholic”, that is, will remain committed to the Soviet religion, but in reality will increasingly distance themselves from Moscow and pursue their pragmatic policies.

- The collapse of the Austrian Empire and the unification of Germany - ultimately, and the Austrian Empire, which existed on the principles of German Catholic dominance, had to break up into secularized nation-states. At the same time, however, German Protestant and regional Catholic states unite into a single national state. United Germany is trying to include Austria and create an empire on a secular-nationalist basis, however, after the collapse of this attempt, it is squeezed within the borders. As a result, the German-speaking space in Europe retains three assembly points: Germany, Austria, and the German-speaking part of Switzerland. If we talk about our analogies, we cannot rule out attempts to unite Russian (Eastern Slavonic) territories into a single state on a purely nationalistic basis around the new center. But with high probability it can be assumed that the diverse Russian (Ruthenian) space will retain several assembly points and independent centers.

Of course, we cannot talk about full compliance and reproduction in Eurasia of the corresponding stages of European history. Yes, and the times today are different - what used to take centuries, can now occur over decades. However, the main meaning of the Westphalian revolution - the transition from the hegemonic imperial system to the system of balance of nation-states becomes evidently relevant for central Eurasia.

Information