Millennium Roadmap

It is known that Russian statehood arose precisely on the river routes - first of all, “From the Varangians to the Greeks”, from ancient Novgorod to ancient Kiev. But they usually forget that the rivers remained the main “roads” of Russia throughout the subsequent thousand years, right up to the beginning of mass railway construction.

Genghis Khan's Road Heritage

The first to relocate a noticeable amount of people and cargo outside the river “roads” across Russia were the Mongols during their invasion. By inheritance from the Mongols of Moscow Russia, transport technologies were also acquired - the system of "pits", "Yamskaya chase". “Yam” is a Mongolian “road”, “way” distorted by the Muscovites. It was this well-thought-out network of posts with prepared replacement horses that made it possible to connect the vast, sparsely populated area of Eastern Europe into one state.

The Yamskoy Order, the distant ancestor of the Ministry of Railways and the Federal Postal Service, is first mentioned in 1516. It is known that under Grand Prince Ivan III, more than one and a half thousand new “pits” were established. In the XVII century, immediately after the end of the Troubles, for many years Yamskoy order was headed by the savior of Moscow, Prince Dmitry Pozharsky.

But the land roads of Muscovy performed mainly only administrative and postal functions - they moved people and information. Here they were at their best: according to the recollections of the ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire, Sigismund Herberstein, his messenger covered the distance in 600 versts from Novgorod to Moscow in just 72 hours.

However, the situation with the movement of goods was quite different. Until the beginning of the XIX century in Russia there was not a single mile and a half of hard-surfaced road. That is, two out of four seasons - in spring and autumn - the roads were simply not available as such. The laden cart could only be moved there with heroic efforts and at a snail's speed. It's not just the dirt, but also the rising water level. Most of the roads — in our concept of ordinary paths — went from ford to ford.

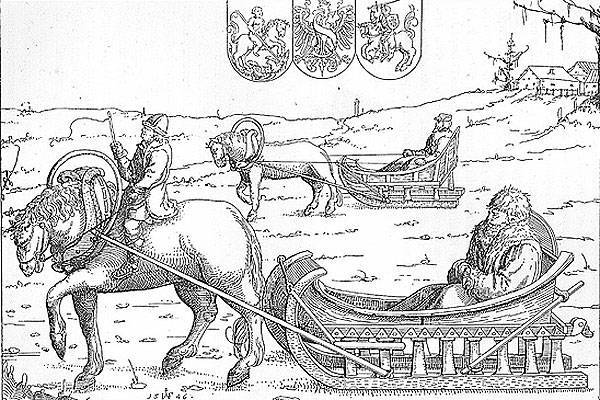

The situation was saved by a long Russian winter, when nature itself created a convenient snowy path — a “winter road” and reliable ice “crossings” along frozen rivers. Therefore, the overland movement of goods in Russia to the railways was adapted to this change of seasons. Every autumn in the cities there was an accumulation of goods and goods, which, after the establishment of snow cover, moved around the country with large wagons of dozens and sometimes hundreds of sledges. Winter frosts contributed to the natural storage of perishable products - in any other season, with the storage and preservation technologies that were almost completely absent then, they would have rotted on a long road.

According to the memoirs and descriptions of Europeans of the 16th — 17th centuries that have come down to us, several thousand sleds with goods arrived in winter Moscow every day. The same meticulous Europeans calculated that the transportation of the same cargo on a sledge was at least two times cheaper than its own transport by a cart. It played a role not only the difference in the condition of roads in winter and summer. Wooden axles and wagon wheels, their lubrication and operation were at that time a very complicated and expensive technology. Much more simple sleds were deprived of these operational difficulties.

Pathways of shackles and postal

For several centuries, land roads played a modest role in the movement of goods, for good reason they were called “postal routes”. The center and main hub of these communications was the capital - Moscow.

It is not by chance that even now the names of Moscow streets remind you about the directions of the main roads: Tverskaya (to Tver), Dmitrovskaya (to Dmitrov), Smolenskaya (to Smolensk), Kaluzhskaya (to Kaluga), Ordynka (to Ordu, to the Tatars) and others. By the middle of the XVIII century, the system of “postal routes” intersected in Moscow was finally formed. The St. Petersburg highway led to the new capital of the Russian Empire. The Lithuanian highway led to the West - from Moscow via Smolensk to Brest, with a length of 1064 versts. Kiev road to the "mother of Russian cities" consisted 1295 versts. Belgorod Road Moscow - Oryol - Belgorod - Kharkov - Elizavetgrad - Dubossary, which is a mile-long 1382, led to the borders of the Ottoman Empire.

They went to the North along the Arkhangelsk road, the Voronezh road (Moscow - Voronezh - Don region - Mozdok) went to the south in 1723 versts and the Astrakhan road (Moscow - Tambov - Tsaritsin - Kizlyar - Mozdok) to 1972 versts. By the beginning of the long Caucasian War, Mozdok was the main communications center of the Russian army. It is noteworthy that it will be already in our time, in the last two Chechen wars.

The Central Russia was connected with the Urals and Siberia by the Siberian Road (Moscow - Murom - Kazan - Perm - Yekaterinburg) with a length of 1784 versts.

The road to the Urals is probably the first stories Russia deliberately designed and built.

This is the so-called Babinovskaya road from Solikamsk to Verkhoturye - it connected the Volga basin with the Irtysh basin. Artem Safronovich Babinov "designed" her on the instructions of Moscow. The path open to them in the Trans-Urals was several times shorter than the previous one, along which Yermak went to Siberia. Since 1595, the road has been built for two years by forty peasants sent by Moscow. According to our concepts, this was only a minimally equipped path that was barely cleared in the forest, but by the standards of that time, a completely solid track. In the documents of those years, Babinov was called “the leader of the Siberian road”. In 1597, the 50 residents of Uglich, accused in the case of the murder of Tsarevich Dmitry and exiled to the Urals to build the Pelymsky jail, were the first to experience this road on themselves. In Russian history, they are considered the first exiles to Siberia.

Without hard coating

By the end of the 18th century, the length of the “postal routes” of the European part of Russia was 15 thousands of miles. The road network was getting thicker towards the West, while east of the Moscow-Tula meridian, the density of roads was sharply decreasing, sometimes tending to zero. In fact, only one Moscow-Siberian highway led to the east of the Urals with some branches.

The road through all of Siberia began to be built in the 1730 year, after the signing of the Kyakhta treaty with China - systematic caravan trade with the most populated and wealthy state in the world was then considered as the most important source of income for the state treasury. In total, the Siberian Road (Moscow - Kazan - Perm - Yekaterinburg - Tyumen - Tomsk - Irkutsk) was built over a century, having completed its equipment in the middle of the XIX century, when it was time to think about the Trans-Siberian railway line.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, there were no roads with hard weather in Russia at all. The capital road between Moscow and St. Petersburg was considered the best way. It began to build on the orders of Peter I in the 1712 year and ended only after 34 year. This road, a length of 10 km in 770, was built by a specially created State Road Office using advanced technology then, but still they did not dare to make it stone.

The “Capital Route” was built in the so-called fascine way, when they dug a pit a meter or two deep across the whole route and fascias and bundles of rods were put into it, pouring layers of fascines over the ground. When these layers reached the level of the earth's surface, a scaffolding platform was laid on them across the road, on which a shallow layer of sand was poured.

The “Fashinnik” was somewhat more convenient and reliable than the usual path. But also on it the loaded cart went from the old capital to the new whole five weeks - and this is in the dry season, if there was no rain.

In accordance with the laws of the Russian Empire, the peasants of the respective locality were supposed to repair the roads and bridges. And the "road service", which mobilized rural men with their tools and horses, was considered by the people one of the most difficult and hated.

In sparsely populated regions, roads were built and repaired by soldiers.

As the Dutch envoy Deby wrote in April 1718 of the year: “Tver, Torzhok and Vyshniy Volochek are inundated with goods that will be transported to St. Petersburg by Lake Ladoga, because carriers have refused to transport them dry by expensive road horse and bad condition of the roads ...”.

A century later, in the middle of the 19th century, Lessl, a professor at the Polytechnic School of Stuttgart, described the Russian roads in the following way: “Imagine, for example, in Russia a freight train from 20 — 30 carts loaded with 9 centners into one horse, following one another. In good weather, the convoy moves without obstacles, but during prolonged rainy weather, the wheels of the wagons sink into the ground to the axles and the whole convoy stops for whole days in front of the streams that overflowed their banks ... ”

Volga flows into the Baltic Sea

For a considerable part of the year, Russian roads buried in mud were literally in the literal sense of the word. But the domestic market, though not the most developed in Europe, and active foreign trade annually required mass cargo traffic. It was provided by completely different roads - numerous rivers and lakes of Russia. And from the era of Peter the Great, a developed system of artificial channels was added to them.

The main export goods of Russia from the XVIII century - bread, hemp, Ural iron, wood - could not be massively transported through the whole country by horse-drawn transport. It required a completely different carrying capacity, which could only give sea and river vessels.

The small barge with a crew of several people, most widespread on the Volga, took 3 thousands of poods of cargo — this cargo took over a hundred carts, that is, it required at least a hundred horses and the same number of people. An ordinary boat on the Volkhov lifted a little more than 500 pounds of cargo, easily replacing twenty carts.

The scale of water transport in Russia clearly shows, for example, such a fact of the statistics that reached us: in the winter of 1810, because of early frosts on the Volga, Kama and Oka, 4288 vessels froze into ice far from their ports. In terms of capacity, this number was equivalent to a quarter of a million carts. That is, river transport on all waterways of Russia replaced at least a million horse-drawn carts.

Already in the XVIII century, the production of iron and iron became the basis of the Russian economy. The center of metallurgy was the Urals, which exported its products. Mass transportation of metal could be provided exclusively by water transport. The barge, loaded with Ural iron, sailed in April and reached St. Petersburg in the fall, during one navigation. The path began in the tributaries of the Kama on the western slopes of the Urals. Further downstream, from Perm to the confluence of the Kama and the Volga, here began the hardest part of the journey - up to Rybinsk. The movement of river vessels against the current was provided by barge haulers. The cargo ship from Simbirsk to Rybinsk, they dragged a half or two months.

The Mariinsky water system started from Rybinsk, and with the help of small rivers and artificial canals, it connected the Volga basin with St. Petersburg via the White, Ladoga and Onega lakes. From the beginning of the 18th century until the end of the 19th century, St. Petersburg was not only the administrative capital, but also the largest economic center of the country - the largest port of Russia, through which the main flow of imports and exports passed. Therefore, the city on the Neva with the Volga basin was connected by as many as three “water systems”, conceived by Peter I.

It was he who began to form and the new transport system of the country.

Peter I first thought out and began to build a system of canals connecting together all the big rivers of European Russia: this is the most important and now completely forgotten part of his reforms,

to which the country remained loosely connected by a conglomerate of isolated feudal regions.

Already in the 1709 year, the Vyshnevolotskaya water system began to work when channels and sluices connected the Tvertsa river, the tributary of the upper Volga, to the Tsnoy river, along which a continuous waterway runs through Lake Ilmen and Volkhov to Lake Ladoga and the Neva. Thus, for the first time, a single transport system appeared from the Urals and Persia to the countries of Western Europe.

Two years earlier, in 1707, the Ivanovsky Canal was built, connecting the upper reaches of the Oka River through its tributary Upu with the Don River - in fact for the first time the huge Volga River Basin was connected with the Don Basin, which could link trade and freight from the Caspian Sea to the Urals with the regions Black and Mediterranean Seas.

For ten years, the Ivanovsky Channel built 35 of thousands of driven away peasants under the leadership of German colonel Brekel and English engineer Per. With the beginning of the Northern War, the captured Swedes joined the serf builders. But the British engineer was wrong in the calculations: studies and measurements were carried out in the year of extremely high groundwater levels. Therefore, the Ivanovo Canal, despite the 33 gateway, initially experienced problems with filling with water. Already in the 20th century, Andrei Platonov would write about the drama of the production novel of the era of Peter I - “Epiphany Gateways.

The channel that connected the basins of the Volga and the Don, despite not all of Peter's ambitions, did not become a bustling economic route - not only because of technical errors, but primarily because there was still a century before the conquest of the Black Sea basin of Russia.

The technical and economic fate of the canals connecting the Volga with St. Petersburg was more successful. At the end of the reign of Peter I, the Novgorod merchant Mikhail Serdyukov, who turned out to be a talented self-taught hydrotechnologist, improved and brought to mind the Novgorod merchant Mikhail Vishnevolotskaya, built for military purposes in a hurry for 6 for years by six thousand peasants and Dutch engineers. True, at the birth of this man was called Borono Silengen, he was a Mongol, who was captured as a teenager by Russian Cossacks during one of the clashes on the border with the Chinese Empire.

The former Mongol who became Russian Mikhail, having studied the practice of the Dutch, improved the gateways and other structures of the canal, raised its carrying capacity twice, reliably connecting the newborn Petersburg with central Russia. Peter I, in joy, handed over the canal to Serdyukov in the hereditary concession, and since then his family has been receiving 5 kopecks for almost half a century from the length of each vessel passing through the canals of the Vyshnevolotsk water system.

Burlaki against Napoleon

The entire 18th century in Russia was unhurried technical progress of river vessels: if in the middle of the century a typical river barge on the Volga received an average of 80 tons of cargo, then at the beginning of the XIX century a bark of similar size took already 115 tons. If in the middle of the XVIII century, on the Vyshnevolotsk water system, thousands of ships passed an average of 3 annually in St. Petersburg, by the end of the century their number doubled and, moreover, 2 — 3 thousands of rafts with forest for export were added.

The idea of technical progress was not alien to people from the government boards of St. Petersburg. So, in 1757, on the Volga, on the initiative of the capital of the empire, so-called engine ships appeared. These were not ships, but ships moving at the expense of the gate, rotated by bulls. The ships were intended for the transportation of salt from Saratov to Nizhny Novgorod, each raising 50 thousands of pounds. However, these "cars" functioned for the entire 8 years - barge haulers turned out to be cheaper than bulls and primitive mechanisms.

At the end of the 18th century, a barge carrying bread from Rybinsk to St. Petersburg cost over one and a half thousand rubles. The loading of the barge was done in 30 — 32 rubles, the state duty was 56 rubles, while the payment for pilots, barge haulers, horsemen and divers (that was the name of the technical specialists who served the canal locks) was already 1200 — 1300 rubles. According to the preserved statistics of 1792, the largest merchant in Moscow turned out to be Arkhip Pavlov, a Moscow merchant - that year he spent from Volga to Petersburg 29 baroque with wine and 105 with Perm salt.

By the end of the 18th century, Russia's economic development required the creation of new waterways and new land roads. Many projects appeared already under Catherine II, the aging empress issued appropriate decrees, for the implementation of which the officials did not constantly find money. They were found only under Paul I, and the grandiose construction work was already completed in the reign of Alexander I.

Thus, in 1797 — 1805, the Berezinsky water system was built, connecting the basin of the Dnieper with the Western Bug and the Baltic by channels. This aquatic “road” was used to export Ukrainian agricultural products and Belarusian forest to Europe through the port of Riga.

In 1810 and 1811, literally on the eve of Napoleon’s invasion, Russia received two additional channel systems, the Mariinsky and Tikhvin, through which the country's increased traffic flow went from the Urals to the Baltic. The Tikhvin system became the shortest route from the Volga to St. Petersburg. It began at the site of the modern Rybinsk reservoir, ran along the tributaries of the Volga to the Tikhvin connecting channel, which led to the Syas River, which flows into Lake Ladoga, and the Neva River. Since even in our time Lake Ladoga is considered difficult for navigation, along the coast of Ladoga, completing the Tikhvin water system, a bypass channel was built, built under Peter I and improved already under Alexander I.

The length of the entire Tikhvin system was 654 versts, of which 176 were sections that were filled with water only with the help of sophisticated gateway technology. In total, 62 gateways worked, of which two were auxiliary, which served to collect water in special tanks. Tikhvin system consisted 105 cargo piers.

Every year, 5 — 7 thousands of ships and several thousand more forest rafts passed through the Tikhvin system. All the gateways of the system served only three hundred technicians and employees. But 25 — 30 of thousands of workers were involved in escorting ships along the rivers and canals of the system. Taking into account the movers on the quays, only one Tikhvin water system required more than 40 thousands of permanent workers - huge numbers for those times.

In 1810, goods for the sum of 105 703 536 rubles were delivered to St. Petersburg by river transport from all over Russia. 49 cop

For comparison, approximately the same amount was the annual budget revenues of the Russian Empire at the beginning of the XIX century on the eve of the Napoleonic wars.

The Russian water transport system played a strategic role in the 1812 victory of the year. Moscow was not a key hub of communications in Russia, so it was rather a moral loss. Systems of the Volga-Baltic channels reliably connected Petersburg with the rest of the empire even at the height of the Napoleonic invasion: despite the war and a sharp drop in traffic volumes in the summer of 1812 of the Mariinsky system, the capital of Russia received cargo for 3,7 million rubles, for Tikhvin one - for 6 million.

BAM Russian Tsars

Only direct expenses of Russia for the war with Napoleon at that time amounted to a fantastic amount - more than 700 million rubles. Therefore, the construction of the first roads with hard stone pavement started in Russia under Alexander I progressed with an average speed of 40 versts per year. However, by the 1820 year, the Moscow-Petersburg all-weather highway was operational and for the first time the regular movement of passenger stage was organized by it. A large carriage on 8 passengers, thanks to interchangeable horses and a stone-paved highway, covered the distance from the old to the new capital in four days.

After 20 years, such highways and regular stagecoach functioned already between Petersburg, Riga and Warsaw.

The inclusion of a large part of Poland within the borders of Russia required the empire to build a new canal. In 1821, Prussia unilaterally imposed prohibitive customs duties on the transit of goods to the port of Danzig, blocking access to the sea for Polish and Lithuanian merchants who became citizens of Russia. In order to create a new transport corridor from the center of the Kingdom of Poland to the Russian ports in Kurland, Alexander I approved the “August Channel” project a year before his death.

This new water system connecting the Vistula and the Neman was built 15 years. Construction slowed down the Polish uprising 1830 of the year, an active participant in which was Colonel Prondzinsky, the first head of the construction work, who had previously served in the army of Napoleon as a military engineer and pardoned the creation of the Kingdom of Poland.

In addition to the Augustow Canal, which passed through the territory of Poland, Belarus and Lithuania, the indirect result of the Napoleonic invasion was another channel, dug far to the north-east of Russia. North-Catherine Canal on the border of the Perm and Vologda provinces connected the basins of the Kama and Northern Dvina. The canal was conceived during the reign of Catherine II, and its previously unhurried construction was forced during the war with Napoleon. The North Catherine Canal, even if the enemy reached Nizhny Novgorod, allowed the Volga basin to be connected through the Kama to the port of Arkhangelsk. At that time it was the only canal in the world built by hand in deep taiga forests. Created largely for purely “military” reasons, it never became economically viable, and was closed 20 years after construction, thereby anticipating the history of BAM after a century and a half.

By the middle of the 19th century, the canal system of the Russian Empire reached its peak for the economy and the life of the country.

But 800 kilometers of the total length of all Russian channels looked not at all impressive against the background of their counterparts in Western Europe. For example, the length of all British shipping channels exceeded 4000 kilometers. The length of the channels of France was close to 5000, and Germany over 2000 kilometers. Even in China, the length of only the Imperial Canal, through which Beijing was supplied with rice, exceeded the length of all the channels of Russia combined.

In the middle of the XIX century, the maintenance of one mile of waterways in Russia was spent around 100 rubles, in France 1765 rubles, in Germany 1812 rubles. Both in Europe and in China, the channels operated, if not year-round, then at least most of the year. In Russia, they functioned at best 6 months from 12, or even less.

Even after the start of mass railway construction, channels, thanks to new technologies, competed with the locomotive and rails. So, thanks to the steamboats, the throughput of the Tikhvin canal system in 1890's increased fourfold compared to 1810 in the year, and the transit time from Rybinsk to St. Petersburg decreased threefold. The load capacity of the first rail cars did not exceed 10 tons, while the canals of the Tikhvin system allowed the movement of vessels with a carrying capacity of more than 160 tons.

In fact, in Russia, canals and river routes were relegated to the background by railways only to the beginning of the 20th century.

Information