Western campaign of Subedei and Jebe: Battle of Kalka

Battle of Kalka

В previous article we talked about the western campaign of the tumens Subedei and Jebe, the initial goal of which was to search for Khorezmshah Muhammad II. After his death, they, bypassing the Caspian Sea from the south, moved north, defeating the troops of the Georgian king George IV (son of the famous Queen Tamara, died in battle on January 18, 1223), Lezgins, Alans and inflicting a crushing defeat on the Kipchaks near the Don River. Pursuing them, they went to the steppes of the Southern Black Sea region and to the Crimea.

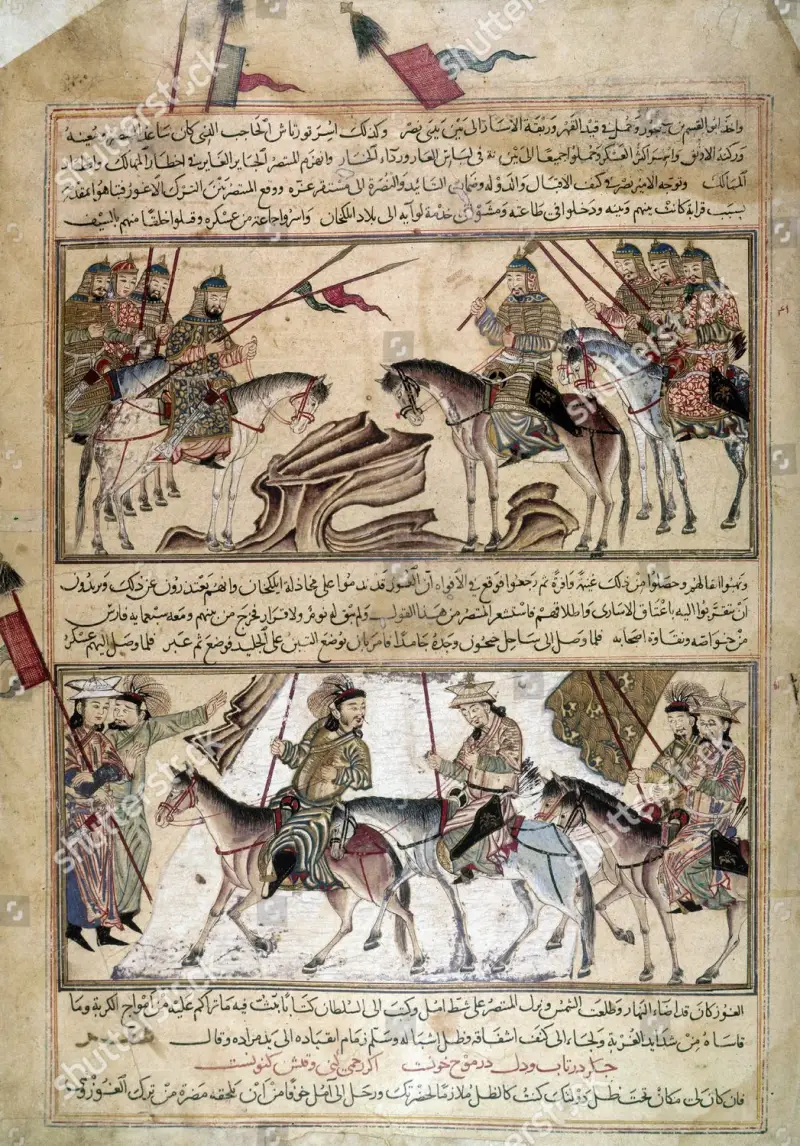

Mongol army. Miniature from the “Collection of Chronicles” of Rashid ad-din. 1301–1314

Part of the Kipchaks, led by Khan Kotyan, retreated to the borders of the Russian principalities. They were well known in Rus' under the name Polovtsy. According to the most common and reliable version, they were named so because of their characteristic straw-yellow hair color (from the word “polova” - straw). By the way, the Byzantine name “Cumans” comes from an adjective meaning pale yellow color.

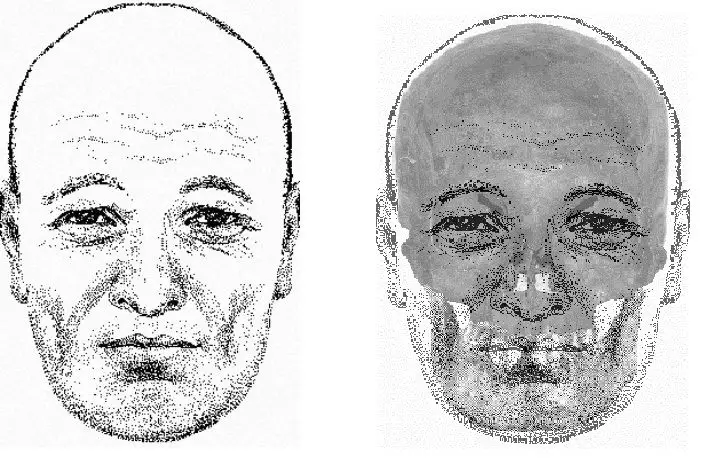

A Polovtsian from a burial near the village of Kvashnikovo, reconstruction by G. V. Lebedinskaya - head of the Laboratory of Plastic Reconstruction of the Institute of Ethnography of the USSR Academy of Sciences (Institute of Anthropology and Ethnology of the Russian Academy of Sciences), author of the methodological manual “Face Reconstruction from the Skull”

However, some argue that the newcomers were originally called “Onopolites” or “Onopolites” - that is, people from the other half of the land, lying beyond the left bank of the Dnieper. And in Hungary the Kipchaks were known as Kuns.

The Polovtsians appeared in Rus' in 1055 (a year after the death of Yaroslav the Wise), and their first raid on the Russian lands was recorded in 1060. The Polovtsians turned out to be restless neighbors, but not too dangerous, since they did not know how to storm cities. They posed the greatest danger as allies of some prince, who invited them to go on campaigns to the land of their neighbors and relatives.

The union of Russian princes and Polovtsian khans was traditionally sealed by the marriage of their children. As we remember, the mother of Andrei Bogolyubsky was a Polovtsian - and therefore M. Gerasimov, in his scandalous reconstruction of 1941, portrayed this Russian prince as a Mongol. This is what Andrei Bogolyubsky looks like on the correct reconstruction by V. N. Zvyagin (Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Forensic Personal Identification of the Russian Center for Forensic Medical Examination of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation):

Graphic reconstruction of the appearance of Andrei Bogolyubsky (left) and checking the correspondence of the graphic image to the skull (right) according to V. Zvyagin

The reason for the transformation of a Caucasian skull, gravitating toward “Nordic forms,” into a “Mongoloid facial character” in the sculptural reconstruction of M. M. Gerasimov is not entirely clear. Perhaps, when working on the bust of the prince, Gerasimov wanted to draw attention to his Russian-Polovtsian origin. In those years, it was mistakenly believed that the Mongoloid racial type was dominant among the Cumans.”

In general, very soon almost all Russian princes became relatives of the Polovtsian khans. The famous Konchak also gave his daughter in marriage to his son, Prince Igor, who was captured by him. And the daughter of Khan Kotyan became the wife of the Galician prince Mstislav Udatny.

Khan Kotyan presents gifts to Mstislav Udatny. Miniature of the Facial Chronicle Code

First meeting between Russians and Mongols

The official version of those events says that the Polovtsian Khan Kotyan turned to the Russian princes for help with the words:

He was also supported by his son-in-law, Mstislav Udatny, who told the Russian princes gathered for the council:

However, we know that Subedei and Jebe did not have the task of conquering the Polovtsian lands, and they did not plan to stay in the Black Sea steppes. And they certainly weren’t going to take Russian cities by storm. Nevertheless, when reading the documents, one gets the impression that the Mongols are literally standing on the border of Russian lands, a clash with them is inevitable, the only question is where it will take place. And therefore the Russian princes make a forced decision:

In general, everything is simple, clear and logical - and at the same time completely wrong.

The fact is that the Mongols at the time of Kotyan’s arrival were very far from the Russian borders - they fought in the Crimea and the Black Sea steppes. And Mstislav’s father-in-law, who called for unification to fight foreigners, actually deserted from that war - he left on his own and took with him about 20 thousand soldiers. The comrades he left behind already had little chance of success, but now they were doomed to inevitable defeat.

And Kotyan is really trying to create an anti-Mongol alliance - but, apparently, not defensive, but offensive. He either deceived the Russian princes: by exaggerating his colors extremely, he convinced them that the danger was real and the invasion of the “wild Mongols” was inevitable. Or, on the contrary, with a story about the weakness of strangers, he seduced them with the opportunity to easily defeat them and take away rich booty.

Judging by the carelessness of the movement of the troops of the Russian squads and the adventurous beginning of the battle, into which Mstislav Udatny got involved without waiting for other princes (let us note, by the way, that Udatny is not a daredevil, but only a lucky one), it is the second assumption that may turn out to be correct.

Soon the Mongol ambassadors appeared and declared:

Mstislav Udatny and Kotyan seemed to be very afraid that the Mongols would leave without entering the battle, and therefore the ambassadors were killed. The Polovtsians already knew that the Mongols did not forgive this and by killing the ambassadors they deliberately provoked them into battle - again, hoping for an easy victory over them.

The situation was aggravated by the fact that one of Subedei’s two sons, Chambek, was part of that embassy, and now the Russian princes became the bloodlines of the temnik. Since reconciliation was now impossible, no one laid a finger on the Mongols of the second embassy, although their speeches were much more militant:

With what forces did the Russian princes oppose the Mongols?

The squads of the Kyiv, Chernigov, Smolensk, Galicia-Volyn, Kursk, Putivl and Trubchev principalities went on a campaign. They did not wait for the detachment of the Vladimir Principality, which was led by Vasilko of Rostov - he only managed to reach Chernigov, where he received news of the defeat on Kalka.

But even without the Vladimirs, the total number of the Russian army reached 30 thousand people; it was joined by 20 thousand Polovtsians, who were led by the Przemysl thousand Yarun - the governor of Mstislav Udatny. The Brodniki (who later went over to the side of the Mongols) also joined the Russian-Polovtsian army.

Such a persistent desire to definitely fight the Mongols becomes understandable: both Kotyan and the Russian princes were confident that, having such a significant advantage in strength, they would easily defeat the tumens of Subedei and Jebe, who had already suffered losses.

However, the Russian squads did not have a common command, and the two most authoritative princes, Mstislav of Kiev and Mstislav of Galitsky, thought more about how all the glory and spoils would not go to their rival. It seems that they did not even imagine joint actions. As a result, at the decisive moment on May 31, 1223, their troops found themselves on different banks of the Kalka River.

N. Fomin. “Three Mstislavs” (“Before the Battle of Kalka”)

At the forefront of the allied army were the Polovtsians and the troops of Mstislav Udatny. The Mongols, following their favorite tactics, retreated, leading the enemy troops with them, constantly disturbing them and exhausting them with constant small skirmishes.

Mongol horseman, 14th-century Persian miniature

This behavior strengthened Mstislav Udatny in the idea that strangers were weak and afraid to engage in battle. As a result, he apparently decided that he could do without the help of other princes, with whom he did not want to share either glory or spoils.

It must be said that the Mongols also suffered losses during this retreat: as we remember, it was suggested that the experienced commander Jebe was killed in one of the rearguard battles.

However, they achieved the strategic goal: the tired Russian army, stretched for many miles, was brought to the right place, the Russian commander who was considered the most successful was disoriented and entered the battle without waiting for other squads to approach.

A. Yvon. Lithograph “Battle of Kalka”

Battle of Kalka

The feigned retreat of the Mongols lasted 12 days. The largest clash is described in the Ipatiev Chronicle:

Finally, on May 31, 1223, Mstislav Udatny saw Mongol troops ready for battle and, fearing that they would retreat again, attacked them on May 31, 1223, without even warning the other princes about it.

This famous battle is described in 22 Russian chronicles, and is everywhere called the “battle of Kalki.” It probably happened not on one, but on several nearby small rivers.

There is still debate about where exactly this battle took place. The area near the Karatysh, Kalmius and Kalchik rivers is named as a possible location. And in the chronicle “Yuan Shi” Kalka is called the Alitzi River.

According to the Sofia Chronicle, at the first stage of the battle, the Russians overthrew a small Mongol detachment near some river Kalka. At the same time, Mstislav’s warriors captured an enemy centurion, who was handed over to the Polovtsians for reprisals. Perhaps it was he who was mentioned in the first article by the Hungarian historian Stephen Pou who mistook him for Jebe. Then the Russian detachments under the command of Mstislav Galitsky found themselves at another Kalka and, without coordinating their actions with other participants in the campaign, crossed to the other side.

Mstislav Udatny and his son-in-law Daniil Romanovich on the banks of the Kalka, miniature from the Front Chronicle Vault

And the Kiev prince Mstislav the Old and his two sons-in-law began to set up a camp on the opposite bank.

Mstislav Romanovich Old, mosaic at the Golden Gate metro station, Kyiv

Here is how the Ipatiev Chronicle tells about further events:

Acting separately from other units, the troops of Mstislav Udatny, Daniil Volynsky, horsemen of the Chernigov principality and Polovtsians attacked the Mongol vanguard, which, having retreated, brought them under attack from reserve detachments of plate cavalry.

Tatar armored warrior, reconstruction by M. Gorelik

The Polovtsians, who had already dealt with the Mongols, fled in panic from the battlefield, crushing their Russian allies - in the Novgorod and Suzdal chronicles it is their flight that is called the reason for the defeat.

Mongolian cavalry chasing the enemy. Thumbnail from the Collection of Annals of Rashid al-Din, XIV century

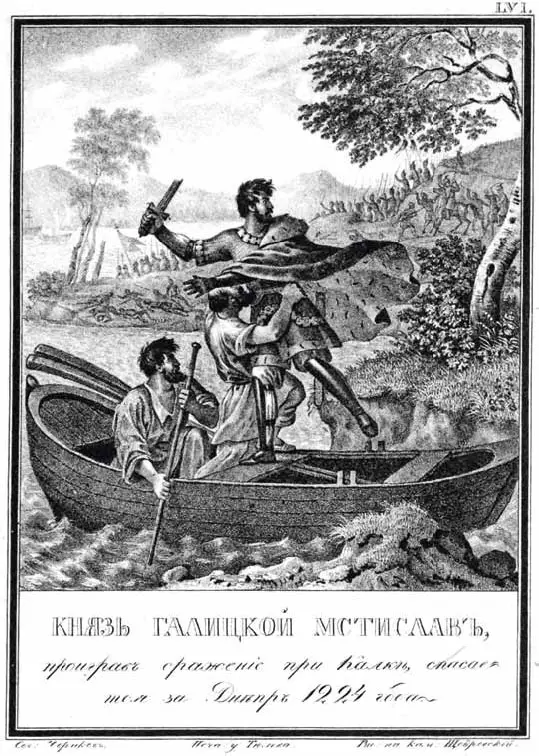

However, Mstislav Udatny showed himself no better then, who fled in the front ranks and, having crossed the Dnieper with part of his squad, ordered all the boats to be chopped up and burned. His son-in-law, the Volyn prince Daniil Romanovich, the future “King of Rus'” and the father-in-law of Andrei Yaroslavich, brother of Alexander Nevsky, fled with him. About 8 thousand warriors remained on the shore, who were cut down by the Mongols of the Tumen of Subedei.

B. Chorikov. “Prince Mstislav Galitsky, having lost the battle of Kalka, escapes across the Dnieper”

Let us recall, by the way, that the famous Igor Svyatoslavich could also flee in 1185, but said:

While the main forces of the Mongols were pursuing the defeated Russian and Polovtsian regiments and destroying them on the banks of the Dnieper, the camp of Mstislav of Kyiv was besieged by units of two commanders - Chegirkhan and Tushikhan. Of particular interest is the name of the second of them, which can be translated as “Bound” (“Hounded by shackles”). Perhaps Tushikhan was a Mongol who was captured by enemies. But it is possible that, like Jebe, he was once captured and agreed to serve Genghis Khan.

The camp of Mstislav of Kyiv held out for another three days. Successfully repelling enemy attacks, Russian soldiers suffered from hunger and thirst, and therefore their leaders seized the opportunity to negotiate decent conditions for retreat. On behalf of the Mongols, negotiations were conducted by a certain “voivode of the Brodniks” Ploskin, who kissed the cross that the Mongols “will not shed your blood.”

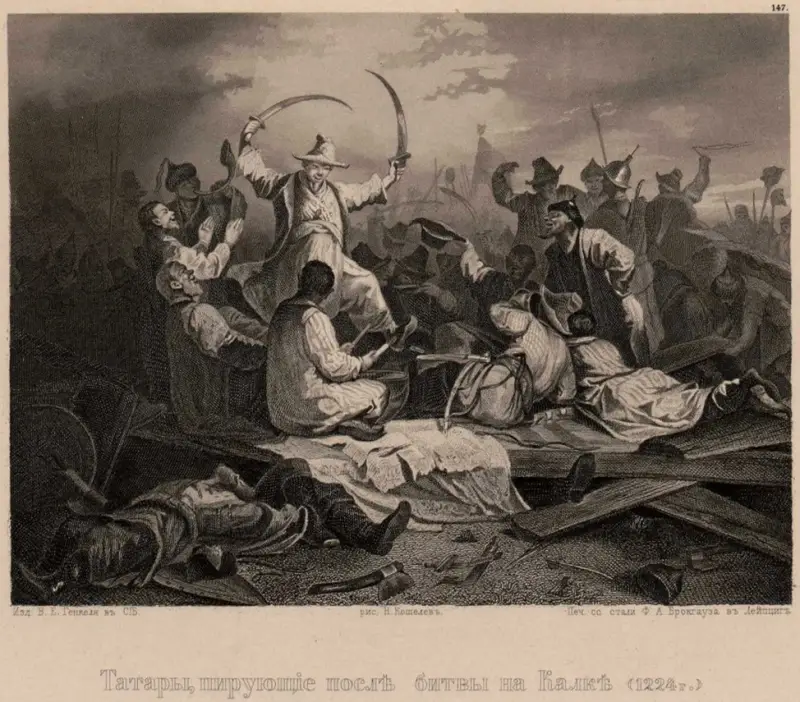

It must be said that the Mongols, in fact, did not shed the blood of the Russian princes: the chronicles claim that the bound captives were laid on the ground - boards were laid on top, on which a feast of the victors was arranged.

N. Koshelev. "Tatars feasting after the Battle of Kalka", 1864

But there is another version of those events, according to which the negotiations with the Russian princes were conducted not by the wanderer Ploskinia, but by the former governor (vali) of the Bulgarian city Khin Ablas (Ablas-Khin), who, having been captured in one of the Caucasian cities, was with the Mongols with 1222 years.

As we remember, the son of Subedei was part of the first Mongol embassy, was killed, and this temnik became the bloodline of the Russian princes. Subedey allegedly ordered to ask: who should be executed for the death of his son - the princes or their warriors? The princes allegedly answered that they were warriors, and then Subedei turned to the warriors:

Then, when the bound princes were placed under the wooden shields of the Kyiv camp, he ordered:

And then it was the turn of the vigilantes - because

Thus, in the battle on Kalka and after it, up to 90% of ordinary soldiers, many boyars and from six to nine Russian princes died. The death of six princes is accurately documented: Mstislav the Old of Kyiv, Mstislav Svyatoslavich of Chernigov, Alexander Glebovich from Dubrovitsa, Izyaslav Ingvarevich from Dorogobuzh, Svyatoslav Yaroslavich from Yanovitsy, Andrei Ivanovich from Turov.

The death of Mstislav the Old led to new strife and a fierce struggle for the Kiev throne. After the victory, the Mongols moved east. But we know that the much more modest victory of the Polovtsians over the troops of Igor Svyatoslavich in 1185 ended with a blow to the Chernigov and Pereyaslavl lands.

And the Mongols in 1223 did not begin to ruin the Russian principalities that remained virtually defenseless, that is, they did not take advantage of the fruits of their victory. This can be considered proof of the thesis that Khan Kotyan deceived his allies: the Mongols in 1223 did not plan to invade Rus', the battle on Kalka was unnecessary and optional for them.

But not useless either: Genghis Khan and his closest associates learned that in the armies of the distant Uruses there were neither any miracle heroes, nor an iron structure of disciplined and well-organized squads, nor a single command.

As a result, in the spring of 1235, at the Great Kurultai, it was decided to send only 4 thousand Mongols on a western campaign against the “Arasyuts and Circassians” (Russians and residents of the North Caucasus) and “as far as the hooves of the Mongol horses will gallop” - 5 times less than there were in tumens of Subedei and Jebe.

The rest of the soldiers of Batu Khan's army were recruited from already conquered territories (10% of all combat-ready men, as well as volunteers); they were significantly inferior to the Mongols in terms of organization and discipline, and in combat training. But, as you know, in the conditions of increasing feudal fragmentation of the Russian lands, this turned out to be quite enough.

In the next article we will continue the story about the western campaign of the Tumen Subedei and Jebe, talk about the “ram battle” of the Mongols with the Volga Bulgars and the return to Genghis Khan’s headquarters.

Information