“Pig War”: how an episode with a pig almost caused a war between the USA and Great Britain

As is known, story humanity is a history of constant wars. Carl von Clausewitz believed that war is a natural continuation of politics: if in the case of peaceful relations the parties (including states) build their relations diplomatically, then in the event of war armed force comes into action, but this is as natural as peaceful diplomatic relations [ 3].

The difference between war and peace, according to Clausewitz, is that “peace” as a form of relationship between different states imposes various restrictions on the use of force, and “war” removes all these restrictions. That is, war, in his opinion, is inevitable, peace is finite and temporary, and it should be considered as a prelude to a future war.

Often, starting a war requires a set of circumstances that would force one state to go to war with another. This set of circumstances is usually cited as the cause of the war, suggesting that if it had been different, the war most likely would not have occurred. And sometimes the reasons that led or could lead to war turn out to be completely ridiculous and phantasmagorical. This can also be said about the failed military conflict for the island of San Juan between the USA and Great Britain.

The historiography of the 1853–1871 San Juan Island dispute, known in the twentieth century as the Pig War, is extensive. However, as the researchers note, the interpretation of these events, changing several times, reflected the political problems and historical fashion of each period.

The central event of this conflict is believed to have been "Pig Day" - June 15, 1859, when an American settler on San Juan Island shot and killed a pig belonging to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), after which the US military and the Royal Military The British navy almost entered into open confrontation.

This pig was the only casualty in the San Juan Island dispute, which was the last border conflict between Great Britain and the United States.

But was the pig really the main instigator of the war?

Chronology of the incident

Photograph of a sheep farm on San Juan Island taken in 1859

On June 15, 1859, Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) sheep farmer Charles Griffin wrote in his farm journal: “An American shot one of my pigs for trespassing!” This incident took place on tiny San Juan Island off the coast of Vancouver Island. During this time, British colonists and American settlers of Puget Sound argued over ownership of the island.

This "quarrel" triggered a chain of events that culminated in the final settlement of the border issues between Great Britain and the United States. Cutler and other American settlers appealed to the US Army, and in response, General William Harney ordered troops to land to occupy San Juan.[4]

A pig was shot under the following circumstances.

American settler Lyman Cutler built himself a small home next to a potato patch near Charles Griffin's farm. This bed was chosen by Griffin's boars - when Cutler discovered that the pig had once again uprooted his potatoes, he shot it next to his estate. Cutler said he then went to Griffin's farm and offered to pay for the dead animal. However, Griffin demanded $100 for the pig, and Cutler considered this price too high, and therefore refused to pay.

Griffin reported the incident to the Governor of British Columbia, James Douglas, telling him that “a man named Cutler, an American, who has just recently settled in my territory, shot one of my pigs this morning, a very valuable boar.” Griffin then described the subsequent confrontation he had with Cutler, adding that Cutler came with "threatening language, openly declaring that he would shoot my cattle if they came near his house."[1]

British Columbia Governor James Douglas, former chief executive of the Hudson's Bay Company

Griffin also told his superiors that he had told Cutler in no uncertain terms that the American “had no right to settle on the island, much less in the center of the most valuable sheep pasture.”

Cutler responded that "he has received assurances from the American authorities in Washington Territory that he has a right, that this is American soil, and that he and all other Americans will be protected and their claims will be recognized on American soil." .

This attitude, which illustrates a strong belief in “manifest destiny” (or “manifest destiny”—the cultural belief that American settlers were destined to spread throughout North America), caused Griffin to fear that his farmland would soon be taken over by the Americans.

Griffin's fears turned out to be justified.

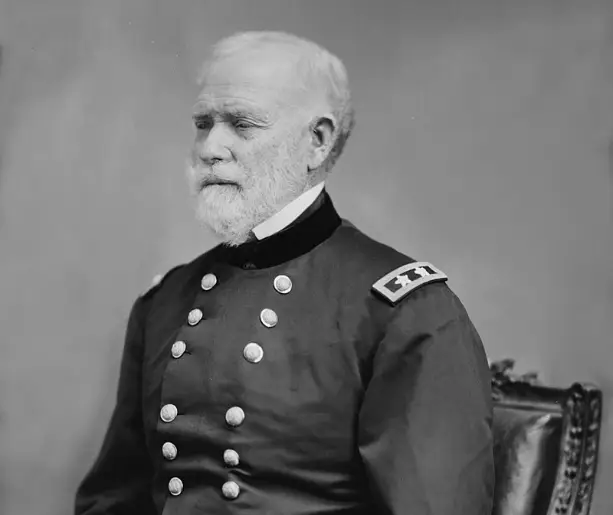

American General William S. Harney, commander of the Pacific forces, soon learned of what had happened on San Juan, received complaints from American settlers, and used them to establish American military control of the island. When word of Griffin's threat against Cutler reached Harney, he reported to his superiors:

General William Selby Harney, participant in the Mexican-American War and Indian Wars.

American soldier William Peck wrote in his diary: “There are rumors of problems surrounding the ownership of San Juan Island in Puget Sound. Simply put, the fact is that General Harney, on behalf of the United States Government, claims and took possession of the island in defiance of the Governor of all British Columbia, Douglas, [who] insists that it is the property of the Hudson's Bay Company, and since General Harney already sent US troops there, there are fears that a clash will occur” [2].

Observing the movements of American troops, Griffin reported this to his superiors. On the evening of Tuesday, July 26, 1859, Griffin received information that a steamship had arrived at Griffin Bay. The next morning he went to investigate and discovered that the United States steamer Massachusetts had arrived with a party of soldiers on board. Griffin went down to the pier and met with the commander of the Jefferson Davis, who informed him that “the United States government is landing these troops to build a military base on the island” [1].

In response to Harney's actions, the British Royal Navy sent ships to challenge the landing of American troops. After a tense standoff, it was decided that armed forces representing both countries would remain on the island in equal numbers until the dispute was resolved.

This joint military occupation lasted twelve years.

The settlement was eventually decided by the German Kaiser Wilhelm I in arbitration, and the island was transferred to the United States; San Juan remains an American island today [1].

British officials did not consider the island as important for the needs of the empire as the local colonists, and therefore no one objected to the decision of the German arbitration. For Britain, the San Juan issue was not as important as a strong economic and military partnership with the United States.

In 1872, British troops abandoned the island and it officially became American territory.

This story, called the "Pig War", is today considered a minor event in Anglo-American relations. Since there was no war, it does not attract much attention. However, judging by the rhetoric of officials and the press, the occupation of San Juan was seen as preparation for a major war.

American soldiers such as William Peck were mildly amused by the pig shooting story; but this fun was overshadowed by the real worry that they would soon be drawn into battle with the British. British officials were even less amused and were very alarmed that they might be drawn into further continental warfare on the “edge of the empire.”[1]

“The pig that almost started the war”: historiography of the conflict for San Juan Island

Canadian historian and researcher of the conflict for San Juan Island Gordon Lyall rightly notes that historians do not always agree on what exactly the “Pig War” is. Some believe that it covers the entire San Juan Island dispute, while others argue that it refers more specifically to the "pig case" itself and the subsequent military confrontation.[1]

However, all historians agree that the main cause of this incident was the Oregon Treaty of 1846. This treaty, signed by the British and American governments on June 15, 1846, was intended to once and for all settle the Oregon Question and establish a permanent border between the two countries at the 49th parallel.

However, the treaty contained significant errors - it stated that the boundary between the territories of the United States and Great Britain was to run west along the specified forty-ninth parallel of north latitude to the middle of the strait separating the continent from Vancouver Island, and from there south through the middle of the said strait and the Fuca Straits to the Pacific Ocean.

However, the authors of the treaty did not take into account that in the middle of the “Fuca Strait” there was a cluster of islands, which made passage through the middle of the strait almost impossible. The water boundary would have to be drawn along the Haro Canal or the Rosario Canal. If the boundary had been chosen along Haro, San Juan Island would have belonged to the Americans; if Rosario had been chosen, the island would have belonged to the British. Neither side could agree on which channel was implied by the agreement.

Why such an oversight was made in an important agreement is not entirely clear [1].

Historian John Long offers several explanations for this oversight: “the incompleteness or inaccuracy of existing maps and, in many cases, the failure of negotiators to use such maps [that] existed [that concerned] the course of the border” [5].

This vague clause in the treaty became the main reason for the controversy over San Juan's ownership that continued for the next twenty-five years.

British colonists and American settlers quarreled over the island for years. In 1853, Governor James Douglas assigned the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, a subsidiary of the HBC, to operate a sheep farm on the San Juan as part of a plan to hold the island. Over the next decade, the farm was surrounded by government by American settlers, who viewed the farm as an encroachment by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) on American territorial rights.

In 1855, American officials in Whatcom County demanded eighty dollars in taxes on the farm. Charles Griffin, the clerk in charge of the farm, refused to pay; and on the evening of March 30, an “armed group” of Americans “managed to steal thirty-four heads of valuable breeding rams with impunity” [5]. A few years later, the already well-known to the reader incident with a pig occurred.

In this regard, the question arises: can it be said that it was the pig that became the main cause of the conflict?

Discussions about the pig's contribution to the conflict have a long history, dating back to the occupation of the island.

On August 24, 1859, while on San Juan Island, the American soldier Peck, mentioned above, wrote in his diary:

This entry shows that the pig incident was a topic of discussion on the island after the landing of the troops.

Some historians write that if not for the incident with the pig, events would have developed completely differently, suggesting that the island would not have been occupied by American troops. Perhaps it would be so.

However, historian Gordon Lyall, for example, disagrees with this opinion.

Since the shooting of the pigs immediately preceded the occupation, it is cited as the cause.

Yes, the pig was shot, then there was a private skirmish between Griffin and Cutler, and then Harney landed troops on the island in response to requests from American settlers to protect their interests. But this sequence of events does not make the pig the cause; it simply becomes a link in a chain of events that goes back to the resolution of the Oregon Question in 1846" [1],

- he writes.

Indeed, the incident with the pig was not entirely unique; similar cases (for example, the theft of sheep, which was mentioned above) had occurred before. The conflict between American and British settlers was escalating, and all it took was a small spark to ignite the flames of war.

It's hard to disagree with historian David Richardson:

The main instigators of the conflict and the main characters in this story were in fact an American general who wanted to become president, and a British governor who could not forget that he was an employee of the Hudson's Bay Company.

A group of sparsely populated islands were part of their selfish competition" [6].

Использованная литература:

[1]. Gordon Robert Lyall. The Pig and the Postwar Dream: The San Juan Island Dispute, 1853–71, in History and Memory. Qualicum History Conference, January 2013.

[2]. C. Brewster Coulter, The Pig War, And Other Experiences of William Peck, Soldier 1858–1862, US Army Corps of Engineers: The Journal of William A. Peck Jr. Medford, Oregon: Webb Research Group, 1993.

[3]. Orekhov A. M. “Eternal Peace” or “Eternal War”? (I. Kant versus K. Clausewitz). [Electronic resource]. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/vechnyy-mir-ili-vechnaya-voyna-i-kant-versus-k-klauzevits.

[4]. Gordon Robert Lyall. From Imbroglio to Pig War: The San Juan Island Dispute, 1853–1871, in History and Memory, BC Studies, 186, Summer 2015.

[5]. Long, John W. Jr., The San Juan Island Boundary Controversy: A Phase of 19th Century Anglo American Relations. PhD Dissertation. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1949.

[6]. David Richardson, Pig War Islands. Eastsound, Wash: Orcas Publishing Company, 1971.

Information