22 hours on the way to the “Panther”: liberation of Soltsy February 20–21, 1944

Burning Salts

In January, Military Review published an article “How Soviet troops liberated Novgorod” Alexandra Samsonov about the Novgorod-Luga operation of early 1944. It illuminates well the general course of those events. But what happened at the ordinary level: how did the liberation of a village or a small town usually proceed? What were the typical difficulties and why, as stated in the mentioned article, “the offensive of the Red Army did not develop as rapidly as originally planned”? Why was it not possible to immediately break through the German Panther line?

Answers to a number of these, so to speak, private questions can be found in stories liberation of Soltsy, one of the regional centers of the Leningrad (now Novgorod) region.

So, at the beginning of January 1944, in the North-West direction, our troops finally achieved great success.

They tried to lift the blockade of Leningrad many times. But the lack of reserves, command errors and skillfully built defenses by the Germans interfered with the plans, and the sacrifices of our troops turned out to be almost fruitless.

More than once the name Soltsy appeared in front plans, because the city stood on the important Novgorod-Porkhov highway, at the end of a kind of bottleneck that forms a section of this highway from Shimsk. The liberation of the city opened a convenient path for the advance of Soviet troops on Porkhov, Pskov, Ostrov, and Dno. But in 1942–1943. the front could not be moved. The fate of the war was decided in other places: near Moscow, Stalingrad, Kursk, then in Ukraine.

Even in 1944, during the Leningrad-Novgorod offensive operation, not everything went according to the original plan. The liberation of Soltsy was scheduled by Headquarters for the end of January, but the stubborn resistance of German troops postponed the operation for three weeks.

Only on February 17 did the general retreat of the enemy begin to the “Panther” defensive line, built by the Germans approximately in the direction of Narva - Pskov - Vitebsk. They sought to break away from pursuit by delaying Soviet troops at intermediate lines and destroying infrastructure. The task of our troops was to drive them away as quickly as possible, not allowing them to leave “scorched earth” behind.

This was the case in the Soltsy region, the liberation of which, after overcoming the German defense at Shimsk, became the goal of the 54th Army of the Leningrad Front.

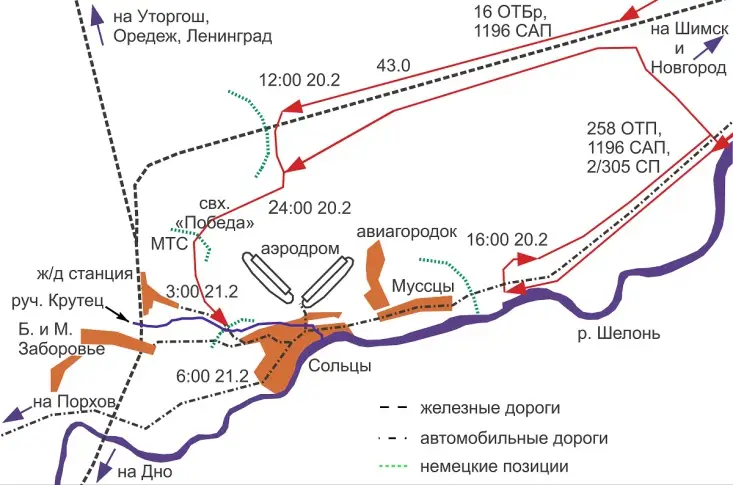

Route of movement of K. O. Urvanov’s group on February 20–21, 1944

The battle for the city took less than a day; our troops entered Soltsy in the early morning of February 21, 1944.

This was only a brief episode of a grandiose war that lasted 1 days. But for the Solsk residents it became a day of joy, long-awaited liberation, and for some of the liberating soldiers - the last day of the military journey. It included many events and characters reflected in military documents, memoirs, and archives. Based on these sources, it is possible to clarify the question of how this happened, as well as to resurrect in memory the names of those who fought and gave their lives to liberate the city.

So, what troops liberated Soltsy?

In 1969, the General Staff gave the following answer to this question asked by the editors of the regional newspaper “Znamya”: “The city of Soltsy, Novgorod region, was liberated on February 21, 1944 by units of the 288th Rifle Division (SD) of the 111th Rifle Corps of the 54th Army and the 16th th separate tank brigade (selected brigade) of the Leningrad Front."

This is an almost verbatim quote from the combat report of the 54th Army: “Units of the 288th SD of the 111th Infantry Division, in cooperation with the 16th brigade, having made a roundabout maneuver, captured... Soltsy.”

We see something similar in G.V. Morev’s book “Soltsy” (1981): “The 288th Infantry Division of Major General G.S. Kolchanov and the 16th Regiment... in cooperation with other units, in particular with the 124th a separate tank regiment (regiment) led an attack on the city.”

The reference book “Liberation of Cities” (1985) also says that the 288th Infantry Division and the 16th Brigade took part in the liberation of Soltsy.

Later, in the book by B.F. Margolis “Town over the Shelon River” (1990), as well as in her preface to the “Book of Memory of the Soletsky District” (1994), there was only an indirect mention of the 124th detachment.

Why the role of the 16th Brigade was forgotten over time is anyone's guess. Perhaps it depended on which unit veterans this or that author communicated with and what documents fell into his hands.

Nowadays, it is easier with documents - a report on the actions of the 16th brigade in February 1944, a post-war manuscript of the history of this brigade, a description of the combat path of the 124th brigade, lists of losses, award sheets have become available...

By comparing them and supplementing them with the memories of old-timers, you can create a more or less complete picture.

On the number and composition of troops

Since the beginning of the Leningrad-Novgorod operation, the 16th brigade suffered heavy losses, and only 15 tanks remained in it: 9 T-34 and 6 light T-60 and T-70, this is a quarter of the staff. The tanks were consolidated into one battalion, commanded by Major Vsevolod Yakovlevich Gorchakov.

The motorized rifle and machine gun battalion (MSB) of the brigade was also greatly reduced: for example, on January 28 it had only 29 “active bayonets,” although later it received some reinforcements.

Apparently, that’s why, back on February 12, the commander of the 16th brigade, Colonel Kirill Osipovich Urvanov, was transferred to the operational subordination of the 1196th self-propelled artillery regiment (SAP) - 21 self-propelled guns SU-76, and the 258th brigade, which fought in Lend-Lease "foreign cars" » – 9 Sherman tanks and 10 Valentine tanks. Judging by the fact that the 258th detachment of tanks had only half of the staff, it also suffered in previous battles.

Commander of the 16th Separate Tank Brigade K. O. Urvanov

Tank battalion commander V. Ya. Gorchakov

Colonel Urvanov was also subordinate to the 2nd battalion of the 305th Infantry Regiment (SP) of the 44th Infantry Division - about 200-300 soldiers.

In total, the forces of this combined mechanized group amounted to 55 tanks and an estimated 400–600 infantrymen. In addition, when moving to Soltsy, the 124th Regiment (10–20 tanks) and the 112th Regiment of the 288th Infantry Division (presumably about 1 soldiers) entered the battle.

On the German side, units of the 38th Army Corps operated near Soltsy. The corps command post arrived in the city in the afternoon of February 17, but already in the afternoon of February 19 it was moved to the bottom. It is difficult to say exactly what forces he left in the rearguard. Sometimes a certain 96th barrage regiment or 191st security battalion is mentioned. But even the battalion, most likely, was only partially present in Soltsy or was incomplete. According to indirect evidence, the Germans had about 100 people with several guns, mortars and machine guns. As will be clear from what follows, their task was only to delay our troops: to force them to turn around from marching columns into battle formations, to spend time on reconnaissance, etc.

It appears that the Soviet command relied on outdated or incorrect partisan and intelligence information and therefore overestimated the enemy's strength and intentions. Reports from 111 IC said that “According to the testimony of local residents, there is a concentration of enemy vehicles and artillery in Soltsy.” The city was seen as "a large and important stronghold of the Germans." It was assumed that about a battalion remained here with the task of providing stubborn resistance to our troops.

The memories of the bloody battles near Novgorod and Shimsk were still fresh. Only this can explain the fact that on our side quite large forces were involved in the attack on Soltsy and that they acted cautiously.

On the way to Soltsy

After crossing Mshaga, Colonel Urvanov divided his group into two columns.

The left one (258th detachment, half of the self-propelled guns, battalion of the 305th regiment) was supposed to go along the highway Pesochki village - Yogolnik village and then through the Solets airfield to the machine and tractor station (MTS) near the station.

The right column (16th brigade and the second half of the self-propelled guns) turned right near the village of Skirino, reached the former Shimsk-Soltsy railway line and moved along it (or along the embankment itself) also towards the station.

The movement of the columns began at 8 a.m. on February 20. This time can be taken as the conditional beginning of the operation to liberate Soltsy. Until its conditional end - at 6 am the next day - 22 hours passed, which are put in the title of the article.

The history of the 16th brigade says: “The enemy, hiding behind small groups on the approaches to the mountains. Soltsy, withdrew the main forces, deploying anti-aircraft automatic guns as anti-tank weapons. The brigade commander decided to strike at the Pobeda state farm, MTS, bypass Soltsy from the north-west, and cut off highways and railways.”

From this the general plan is clear: avoiding a frontal assault on the city, put the Germans in danger of encirclement and force them to leave without a protracted battle. A head-on attack along the Novgorod-Porkhov highway was unprofitable due to the terrain, since in the east the Krutets stream flows into Shelon, covering the main part of the city from the north. Its bed is quite deep, lies in loose sandy soil and, closer to the mouth, is a natural anti-tank ditch.

In addition, at the confluence of the Kruttsa and Shelon, the highway is sandwiched in a defile between the river and a hill from which it could be shot through. The terrain becomes flatter and tank-accessible (albeit with swampy areas) closer to the railway station, where Urvanov’s group was heading.

In a successful scenario, it was possible to cut off the Germans' path to retreat. Judging by the phrase “cut highways and railways,” they planned to close the semi-ring somewhere beyond Soltsy, perhaps near Molochkovsky Bor, pressing the Germans to Shelon. Perhaps there was hope of recapturing the railway bridge intact. Of course, up to a certain point the Germans could escape across the ice to the right bank, but after losing control of the highway their position would become difficult. In addition, the advanced units of the 198th Infantry Division were approaching along the right bank of the Shelon.

The first battle of Urvanov’s right column took place around 12:00 on February 20 at mark 43.0, which is approximately halfway between the village of Pirogovo and the Solets airfield. The lead marching outpost (2nd company of the MSPB, several tanks of the 16th brigade and self-propelled guns of the 1196th glanders) was ambushed, partially surrounded and lost about 20 people killed and wounded.

One of the award sheets relating to this battle spoke about the heroic actions of Alexander Mikhailovich Bogomyakov, commander of the MSPB tank landing company: “In battles in the area of elevation. 43.0 the enemy, having brought up a significant amount of artillery to the infantry battalion, surrounded the 2nd company and cut off Comrade’s company from the tanks. Bogomyakov, going on the attack with numerically superior forces.

Comrade Bogomyakov, having repulsed 5 enemy attacks, launched a counterattack with his company, intending to break through to the encircled. But as a result of five-fold superiority in enemy forces, the company lay down. Comrade Bogomyakov was seriously wounded in the arm. Disregarding this, he shouted “For the Motherland, for Stalin!” rushes into a counterattack a second time. The goal has been achieved. In this fight Comrade. Bogomyakov was mortally wounded.”

It is worth noting that Lieutenant Bogomyakov was at the front for only a month and came, one might say, as a volunteer. Before that he taught at the Omsk Infantry School. In one of his last letters, he told his family that he had finally managed to sign a report with a request to be sent to the active army.

The number of the enemy in the description of this battle seems to be exaggerated and can be estimated at 2-3 platoons of infantry with several machine guns, mortars and anti-tank guns. Otherwise our losses would have been higher.

For this battle, corporal Illarion Antonovich Trukhov, born in 1925, machine gunner MSPB; senior lieutenant Vasily Dmitrievich Dudkin, born in 1910, commander of the 1196th glanders battery; junior lieutenant Matvey Vasilyevich Podlipny, born in 1917, commander of the SU-76 gun; junior lieutenant Arshavir Misakovich Harutyunyan, born in 1920, commander of the SU-76 gun.

A brief description of this battle is also contained in a letter from Alexei Alexandrovich Shatokhin, the former head of the political department of the 16th brigade, sent in 1969 to the secretary of the Soletsky district committee, comrade. Karpov. In addition to the feat of Lieutenant Bogomyakov, Shatokhin noted the valor of the tank company commander Nikolai Demidovich Lobanov, the commander of the forward detachment, who in this battle “organized a perimeter defense and held back the fierce onslaught of the Germans until the main forces of the brigade arrived.”

Tank company commander N. D. Lobanov

Despite such a positive characteristic, in the “tank” awards the 16th selection battle was at elevation. 43.0 is not marked in any way. Perhaps the actions of cap. Lobanov and the tankers as a whole were considered unsuccessful, including due to their squad being ambushed.

On the map, German positions are visible west of mark 43.0, approximately halfway to the MTS, and at mark 43.0 itself there is a flag of the 16th detachment with a time stamp - 17:00. That is, the main forces of the right column arrived at this place only in the evening.

Further, at 18:30, having coordinated cooperation with the 288th Infantry Division, the brigade moved to mark 43.0, where it “shot down the enemy.” Judging by the maps, he retreated approximately to the road connecting Soltsy and the railway station and, possibly, partially to the station itself.

By this time, the left column of Urvanov’s group reached the village of Yogolnik (16:00) and knocked the Germans out of it. This is evidenced, in particular, by the award certificates of Captain Nikolai Efimovich Burobin, born in 1920, adjutant of the senior 1st tank battalion of the brigade, and Sergeant Vladimir Petrovich Gortashkin, born in 1913, T-34 machine gunner of the same battalion.

Then it was decided to change the route: the column returned to the village of Skirino and followed the right column. Apparently, it turned out that it was impossible to pass through the airfield, and pressure on the Germans along the highway could be provided by suitable units of the 288th Infantry Division and the 124th Regiment.

Looking ahead a little, it is worth noting that the decision to redirect the 258th detachment from the highway to a cross-country route turned out to be unsuccessful - foreign cars, especially Shermans, began to fail en masse.

16th brigade on the nearest approaches to Soltsy and during the liberation of the city

Next came the turn to clear the station area from the Germans and enter Soltsy itself.

Notes on the history of the brigade indicate: “Having shot down the enemy in the area of elevation. 43.0, tanks, together with the MSPB landing party, captured the Soviet Union. "Victory" and by 23:00 on February 20, 1944 they captured MTS. The map here also says “swh. Pobeda", although in fact it was a group of outbuildings in the fields, and not the administrative center of the state farm, located on Tsentralnaya Street, now Chernyshevsky Street.

With the date “3:00” on February 21, the maps show the location of Urvanov’s group even closer to the city, near the already mentioned German positions near the road to the railway station, partly along the Krutets stream, in the area of the current Kooperativnaya street. It is worth noting that around here the terrain becomes convenient for crossing tanks across the stream: there is no longer a deep ravine and there are still no swampy areas. Despite the fact that the enemy’s defense is shown as a solid line, it was probably focal, and the fighting on the outskirts of the city was short-lived. In any case, the Germans soon left for the village of Zaborovye.

Several fighters from the MSPB brigade distinguished themselves. This is junior sergeant Vladimir Iosifovich Medved, born in 1925, shooter; Corporal Illarion Antonovich Trukhov, born in 1925, machine gunner; Sergeant Fedor Yakovlevich Shcherbakov, born in 1924, commander of a rifle squad; Sergeant Nikolai Lavrentievich Shchetinin, born in 1918, commander of the anti-tank rifle squad; Corporal Azmulda Zhitbizbaev, born in 1925, rifleman MSPB. Their awards write about “enemy counterattacks” and “heavy mortar fire,” but in reality, judging by our small irretrievable losses, the German resistance was much less than during the day.

Among the tankers of the 16th brigade, the seriously wounded and soon died were noted: senior lieutenant Yuri Yakovlevich Stogov, born in 1920, T-34 platoon commander, senior sergeant Ivan Vasilyevich Elkin, born in 1922, T-34 turret commander, as well as two more turret commanders (senior sergeant Pavel Andreevich Voronin and sergeant Gali Minakhlodovich Ilyasov) and a driver mechanic (Illarion Semenovich Larionov). It is possible that Stogov and Elkin were in the same crew and were wounded when their tank was hit by an enemy shell.

As a result of these night battles, Captain Nikolai Semenovich Shpilev, born in 1922, commander of the machine gun company of the 305th rifle regiment of the 44th infantry division, was also posthumously awarded: “Having been attached with his company, as part of the entire 2nd battalion, 16th tank brigade... was the first to break into the city of Soltsy with his company mounted on tanks. In the area of the Pobeda state farm, the Nazis put up stubborn resistance.

Showing fearlessness and courage and inspiring his subordinates with the example of his heroism, Captain Shpilev suppressed the fire of two German anti-tank guns, knocked out their crews and himself died a heroic death in this battle.” Hence it seems that in other awards the phrase “broke into the city of Soltsy” describes battles in its immediate vicinity, and not in the city itself.

It is unclear whether any fighting took place at the train station. The only mention is in the story “On the Flash,” created by Captain M.D. Kazachinsky, a veteran of the 16th brigade. It describes how at dawn several tanks with landing troops went to the station, knocking out a small German detachment that was adjusting mortar fire.

However, it is, of course, risky to consider what is said in a work of art as a reliable fact. In addition, the maps and text of the history of the brigade do not describe any movements of Urvanov’s group across the line of the October Railway. Apparently, by nightfall it became clear that the Germans were leaving the attack, and therefore Urvanov’s tanks turned towards Soltsy. The time of their entry into the city is indicated in the already mentioned letter from A. A. Shatokhin: “At 3:00 on February 21, 1944, the 16th Tank Brigade immediately captured a powerful enemy resistance center, the city and the railway. Soltsy station. This coincides with the time marked on the maps for the previous positions of the Urvanov group near the road to the railway station and the bed of the Krutets stream. Therefore, the dating “3:00” is most likely arbitrary.

Thus, judging by the documents studied, Urvanov’s group did not fight in the city itself. True, one photograph from the history of the 16th brigade shows a German Pak 35/36 anti-tank gun standing on Soletskaya Street, but it is unclear whether fire was fired from it in the morning, or whether this weapon was abandoned during the retreat.

Local residents don’t even remember the battles in Soltsy. So, K.I. Shvetov said: “The night before there was a small battle at Mussets. It was a small barrier that fired cannons in the direction of Yogolnik to show that there were still Germans in Soltsy. In fact, almost everyone had already left... This barrier had already left by morning, but before that it set the city on fire... Ours did not advance along the highway, but through the station. And they appeared from the direction of the Pobeda collective farm.

By approximately 6:00, parts of the brigade concentrated on the northern outskirts of Soltsy (approximately where the “Star” memorial sign now stands, at the exit towards Porkhov) to refuel vehicles with ammunition, fuel and lubricants and receive a new task - an attack on the city of Dno.

On the participation of the 124th separate tank regiment in the liberation of Soltsy

This is told in the manuscript “The Combat Path of the 124th Division”, which has different but very similar versions, which can be found in the Central Archive of the Ministry of Defense, in the Museum of Military Glory of Tankers of the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts, in the Soletsk Local Lore Museum.

From the short version, we present an extract from the document signed by the chief of staff of the 124th Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel A. S. Tomashevsky: “A ford was found, tanks crossed the river. Shelon (in fact, obviously, Mshagu - Author's note) and, pursuing the retreating enemy, reached the village of Pesochki, where the commander of the 54th Army personally assigned the regiment the task: in cooperation with the 288th Infantry Division to capture the city of Soltsy, after capturing the city - concentrate in the city of Soltsy and go to the reserve.

Continuing the offensive, tanks together with 112 rifle regiments captured the village of Mustsy, one kilometer from Soltsy, by the end of February 20. At dawn on February 21, having gone on the offensive and defeating the enemy’s covering group as part of a reinforced battalion, the tanks captured the city of Soltsy by 6:00, where they concentrated to put their equipment in order, forming the reserve of the commander of the 54th Army.”

There are some questions about this description.

Firstly, why is nothing said about Urvanov’s group, which left for Soltsy on the morning of February 20?

Secondly, it gets light quite late in February, so it’s unclear how it was possible to go on the offensive “at dawn” and defeat the enemy by 6 am?

Another version of the “Combat Path of the 124th Regiment” talks about the interaction of the 124th Regiment with the 16th Regiment during the capture of Soltsy: “During the night of February 21, together with the commander of this brigade and the commander of the 112th Infantry Regiment, a plan was developed for the capture of Soltsy. Early in the morning, our units went on the offensive from three sides. The German covering battalion was crushed and destroyed. By 9 o'clock in the morning... our units captured the city." In this battle, the tankmen of the 3rd tank company, commanded by Cap. Gantoire. As a result of the street battle, which was especially stubborn in the center near the church, the city was completely cleared of the enemy.”

In light of the actions of the 16th brigade described above on February 20–21, it is clear that the authors of the “Combat Path of the 124th Regiment” exaggerate its role in the liberation of Soltsy. For some reason, the time for the liberation of the city was shifted to 9 am. The mention of the “stubborn” battle in Soltsy itself is not supplemented by any specific information, for example, about enemy losses, trophies and prisoners - about what should have followed the “crushing and destruction” of an entire enemy battalion. Soltsy are not mentioned in the award lists of the 124th Division, relating to the time in question.

In confirmation, we can cite another eyewitness account, Solchan resident N. Puchkovsky: “It was quiet and quiet. The Germans are neither seen nor heard... In the house where the hospital was located (the "Russian" hospital in Shkolny Lane - Author's note), there was a large basement... Hospital workers and the remaining patients gathered in the basement. Late in the evening about 10 more people came to us to spend the night together - not so scary.

Night. We are sitting in the basement. Everyone is silent. Silence, no shooting heard. Suddenly we heard someone coming down... Everyone froze: they thought that the Nazis had come to deal with us. The flashlight illuminated us, the entire basement, then the person who entered illuminated himself - there was a red star on his earflap hat... It was a Soviet intelligence officer, a young guy, about 19 years old.

And soon the clanging of the tracks of our tanks was heard, there were more than a dozen of them, they crossed the Krutets (the bridges were blown up) and approached the hospital. "Katyushas" came up behind the tanks..." (Soletskaya Gazeta, September 21, 1999).

The fact of a strong battle in Mustsi is also doubtful. A.P. Lazareva recalled: “... In the morning we all heard the roar of engines and the clanging of tracks... We were all scared, thinking that the Germans were retreating and they could kill us. But then we slowly looked and saw that these were our tanks, there were a lot of them!.. Behind the column of tanks were Katyushas, which looked like houses made of tarpaulin...

Above the column, a black balloon tied to a tank hung on cables. And someone was sitting in the basket and constantly giving commands to someone on the radio... The tankers... turned off the engines, and there was silence. One by one, black and tired, they began to crawl out of the tanks and wash themselves with snow, and one even fell into the snow and lay there for some time... I don’t remember the battle for the village in February 1944. And the column stood for a long time, until the evening of February 20, and then left towards Soltsy...” (interview in the collection “Soltsy, Scorched by the War”).

If we make allowances for the remoteness of the events and the then age of the narrator (6 years), we can assume that the column of the 124th Regiment entered Mustsy not in the morning, but during the day, and moved closer to Soltsy only in the evening. Apparently, the delay was mainly caused by the explosion of the bridge over the Krutets stream near the Ilyinsky Cathedral. Then, along the old cart ramp, the sappers made a flooring of logs, and along it on the morning of February 21, the tanks of the 124th Regiment finally entered the city.

Simple common sense also speaks about the secondary role of 124 otp.

Entering Soltsy along the highway from Novgorod, our people would be trapped: on the left is the Shelon River, on the right and in front are hills. There was no way to do without a workaround maneuver, and it was the 16th brigade that performed it.

Some competition for primacy in the liberation of Soltsy is also observed among other formations and units. Thus, one can find statements about the capture of the city by units of the 364th Infantry Division under the command of Colonel V.A. Verzhbitsky. The same applies to the 198th Infantry Division, about which they write:

“21.02.44/15/00... attacked the enemy in the direction of Soltsy and by 16:XNUMX captured Soltsy, Ilovenko, B. and M. Zabory.” This looks strange, since around this time the XNUMXth Brigade was already crossing Shelon near the village of Relbitsy (which is much to the west of not only Soltsy, but also the villages of Bolshoye and Maloye Zaborovye, erroneously called “Fences”).

Solchan resident I.M. Plaksin fought in the 198th Rifle Division, and his memoirs from 1984 say that on February 21 their regiment entered the city, but there is not a word about military operations. Lieutenant N.S. Morozov, who fought in the same division, in his memoirs of 1969 also only said that on the night of February 20-21, he saw a city and a cathedral from the right bank of the Shelon: “Some building was burning not far away. Before our eyes, a bridge over a river blew up. A fire was also raging at the Soltsy station.”

What explains such contradictions in official reports?

Most likely, something was simply written with embellishments: after a long “sitting” on the almost motionless Leningrad and Volkhov fronts, people finally went forward, and the desire of the authorities to quickly “heroically liberate” something is understandable.

Finally, a curious award was drawn up for Lieutenant Ivan Zoteevich Larionov, born in 1918, platoon commander of the 11th separate combat airborne battalion: “When the commandant of the 2nd Fortified Chudovsky District was tasked with breaking into the city of Soltsy with four vehicles and with machine gunners consisting of 12 people, receiving the task, he said: “We will die, but in Soltsy we will be the first” - which he did. Destroyed one enemy machine gun point and one anti-tank rifle point. In Soltsy, he was the first to hang a flag from his car.”

What’s strange here is the reckless tone, the crazy idea of throwing snowmobiles into street battles, and how they could move along the streets of Solets, where, judging by the photographs in the history of the 16th Regiment, there was almost no snow then. It is not surprising that instead of the requested Order of the Red Star, Lieutenant Larionov received only the medal “For Military Merit.”

Losses of the parties

The liberation of Soltsy, despite the relative weakness of the German resistance, was by no means a simple bloodless walk, especially for the motorized rifle and machine gun battalion of the 16th brigade. The list of irretrievable losses in those days of February 1944 was:

The commander of the MSPB rifle company, Lieutenant Alexander Mikhailovich Bogomyakov (his feat was described above), born in 1919, conscripted from the Altai Territory, killed on February 20, buried in the MTS area.

MSPB platoon commander Lieutenant Viktor Pavlovich Tkachenko, born in 1907, drafted from the Stalin region, killed on February 20, buried 2 km north of MTS.

T-34 platoon commander, senior lieutenant Yuri Yakovlevich Stogov (according to other sources - Pavlovich), born in 1920, drafted from Leningrad, wounded on February 21, died on February 22–23, buried in Soltsy.

MSPB submachine gunner junior sergeant Zenad Khetabovich Galiulin, born in 1925, drafted from Samarkand, killed on February 20, buried 2 km north of MTS.

MSPB submachine gunner Sergeant Andrei Vasilyevich Malikov, born in 1925, called up from Samarkand, killed on February 20, buried 2 km north of MTS.

Anti-tank gun gunner Corporal Dmitry Vladimirovich Pichuzhkin, born in 1902, drafted from the Gorky region, killed on February 26. Since the column “where he was buried” is not filled in for him, and his last name follows Galiulin and Malikov, we can assume that there is a typo in the date and he also died on February 20, and was buried with them.

The commander of the T-34 turret, senior sergeant Ivan Vasilyevich Elkin, born in 1922, was drafted from the Kirov region, wounded and died on February 21, buried in the cemetery at the Chaika state farm, Novgorod region.

Junior Sergeant Ivan Ivanovich Maksimov, born in 1913, drafted from the Smolensk region, wounded on February 21, died on February 25, buried in the cemetery of the village of Sharok, Shim region. Perhaps he died not on the approaches to Soltsy on the night of February 21, but later in the day on the right bank of the Shelon, when the brigade’s reconnaissance collided with the Germans near the village of Grebnya.

Another loss near Soltsy was recorded in the list of the 305th rifle regiment of the 44th infantry division. This is the commander of the machine gun company of the 2nd rifle battalion, Captain Nikolai Semenovich Shpilev, born in 1922, called up from the Altai Territory, killed on February 21, buried at the Pobeda state farm.

The remaining units that were the first to approach Soltsy - the 1196th Sap, 124th Regiment and 258th Regiment, 288th Infantry Division - did not suffer irreparable losses. It is worth noting that the award lists of the 258th detachment, which operated as part of Urvanov’s group, do not contain a single combat episode on February 20–21. Apparently, going up the rear in the column, and also gradually leaving their “foreign cars” along the way due to breakdowns or simply stuck in the mud, the regiment simply did not have time for military clashes.

Unfortunately, of all those who died near Soltsy, only the platoon commander of the MSPb, Lieutenant V.P. Tkachenko, is listed in the city cemetery. The names of the rest were either lost during post-war reburials, or their remains still lie in nameless “burial sites” in the outskirts of the city. Several years ago, at the request of relatives, the name of Lieutenant Bogomyakov was added to the slabs of the Soletsk memorial, but most likely symbolically.

Commander of the tank landing company A. M. Bogomyakov

The report on the actions of the 16th brigade indicates the losses of Urvanov’s group in equipment, apparently irrevocable in combat: one T-34 tank and one SU-76 self-propelled gun. To this, with a degree of convention, we can add about 20 tanks and self-propelled guns, mentioned in the report as temporarily out of action during an off-road detour maneuver (this especially applied to the Lend-Lease Sherman tanks).

German losses can be estimated at several dozen killed and wounded, at least one prisoner (mentioned in the history of the 16th brigade), several anti-tank guns and machine guns. The figures from the report on the actions of the 16th brigade are close to this assessment: “In the battles for Soltsy, the brigade destroyed: 2 anti-aircraft guns, 3 machine guns, 50 soldiers and officers.” The last round figure - 50 people - is clearly approximate. A lot of things happened near Soltsy at that time in the dark, and it’s unlikely that anyone could do accurate calculations. The documents highlight some problems in organizing military operations.

Thus, the report of the 16th brigade pointed out the inappropriateness of the operational subordination of individual regiments to the control of a tank brigade, “since both the personnel and the material available in the arsenal of these regiments for the command and control of the brigade are an innovation, and therefore in difficult terrain Independent causes do not always successfully determine the direction for their action.”

It was also discovered that “the arriving 258th detachment of Foreign tanks (as in the text!) did not have any parts to restore the materiel, despite the fact that there are spare parts in the formation warehouses... A tank with light damage is not restored until the appearance of a damaged or burnt out tank , from which you can remove the necessary part. M4-A2 and MK-3, due to the weakness of the engines and low cross-country ability, are inappropriate to use in forested and swampy areas, since the movement of <these> tanks could only be on roads and dry terrain, which in our conditions led to unnecessary losses. The maneuverability of these tanks is limited."

These lines of the report clearly show some of the reasons that slowed down the Novgorod-Luga operation and did not allow its original plan to be fully realized.

What prevented the Front's Automotive and Tank Directorate from giving instructions in advance on the specifics of using “foreign cars”? What was stopping the regiment itself? Should Urvanov take an interest in this?

Did this not reflect a certain inertia that had developed in the headquarters of the Leningrad and Volkhov fronts over the years of “sitting” on almost motionless fronts, without experience of successful offensive operations into the depths of the enemy’s defense?

Forming mobile mechanized groups from what is at hand to solve urgent problems is a normal practice, and any tank commander at the level of major and above should be prepared for this.

According to the author, part of the responsibility for the failure of a large number of combat vehicles also lay with the command and reconnaissance of the 54 A and 111 SK, which did not reveal in time the intentions and strength of the enemy in the Soltsov region. As a result, a group of tanks was moving in the first echelon, clearly redundant for an assault on the city, and most of the 1196th SUP and 258th Regiment was temporarily lost due to the difficult and useless (many of the remaining vehicles did not take a real part in the battle) march along the rough terrain.

In addition, pushing through the Shimsk-Soltsy bottleneck, in fact, an entire tank corps - the 16th brigade, two tank regiments (124th and 258th) and the 1196th glanders - was poorly supported not only by adequate intelligence, but also sapper support. About the latter, the report of the 16th Brigade says this: “Attached to the 9th Guards. Eng. the battalion fell behind the tanks and did not ensure the timely passage of tanks across the river. Shelon, for which the brigade commander was sent to the disposal of the commander of the 2nd Guards. engineering brigade. Crossing in the Mussa area/across the river. Shelon / construction began on the orders of the commander of the 111th infantry fighting battalion of the 288th infantry division.”

But this crossing was not ready for the outcome on February 21, so the 16th brigade crossed upstream the Shelon by ford on the morning of February 22, losing about another day near Soltsy.

Conclusions

The main role in the liberation of Soltsy was played by the actions of Colonel Urvanov’s group (primarily the 16th brigade), which on February 20 bypassed the city from the north-west in order to avoid a frontal assault, reach tank-accessible terrain and put the German barrier in Soltsy at risk of encirclement.

The 124th Regiment and the 288th Infantry Division played a supporting role in frontal pressure along the Novgorod-Porkhov highway. Due to the nature of the terrain, its mining by the enemy and his undermining of bridges, they conducted almost no active combat operations. Only on the evening of February 20, the 124th Regiment fought a battle for the village of Mustsi, although the scale of this battle is exaggerated in the regiment’s documents.

By the morning of February 21, the Germans left Soltsy and its surroundings, and Urvanov’s group entered the city from the railway station. At the same time, the 124th Regiment entered Soltsy from the village of Mustsy.

The losses of both sides were relatively small - 2-3 dozen killed and wounded. For the Soviet units, the delay of about half a day was more significant, as well as the temporary loss for technical reasons of about half of the equipment due to a detour maneuver off-road.

It is possible that these not very successful results were the reason that none of the military units received the honorary name “Soletskaya”.

PS

The author thanks S.V. Skirchenko and V.I. Lastochkina (Soletsk Local Lore Museum), A.I. Grigoriev (Veliky Novgorod), L.V. Gorchakov (Tomsk), I.M. Khomyakov (St. -Petersburg), A. A. Polishchuk (Megion, Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug) and O. I. Beidu (Moscow).

Photos from the album “History of the 16th Separate Tank Red Banner Dnovskaya Brigade” (TsAMO), personal archives of S.V. Skirchenko and I.M. Khomyakov were used.

Information