Stubby - American hero of the First World War

Stubby

Although I had never heard of him before. But he knew about Balto. First of all, from the 90s cartoon of the same name. But Americans hold Stubby in higher esteem. Let's talk about the stray dog - the mascot of the 102nd Infantry Regiment.

Award

On July 6, 1921, a curious meeting took place at the US Navy building in Washington.

The occasion was a ceremony honoring veterans of the 102nd Infantry Regiment of the 26th Division of the American Expeditionary Forces who participated in the fighting in France during the First World War. The hall was packed with dozens of soldiers of the 102nd Regiment - infantrymen, officers, generals. But one soldier in particular attracted attention. This attention seemed to bother him. The New York Times reported that the soldier was "a little shy and nervous." When he was photographed, he flinched.

The ceremony was presided over by General John Pershing, commander of American forces in Europe. Pershing made a standard speech, noting the heroism and bravery of the soldier. The general solemnly took a medal made of pure gold with engraving from the case and pinned it to the hero’s uniform. In response, the Times reported, the soldier "licked his lips and wagged his little tail." Sergeant Stubby, a short-haired brindle bull terrier mongrel, was officially a World War I hero.

The award is unofficial, but symbolic. She confirmed that Stubby, who also received one wound stripe and three service stripes, is now the greatest war dog in stories countries. He was the first dog ever to receive rank in the U.S. Army, according to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. His glory was noted even in France, where he was also awarded a medal.

John Pershing awards Stubby

All of America knew about Stubby then. He consoled wounded soldiers on battlefields under fire. It was said that he could smell poisonous gas, barking warnings in the trenches. He even captured a German soldier. These exploits made the dog a celebrity.

He met with three sitting presidents, traveled around the country to events honoring veterans, and earned $60 for three days of theatrical performances, more than twice the weekly salary of the average American at the time.

For nearly a decade after the war, until his death in 1926, Stubby was the most famous animal in the United States.

Mongrel at the University

Nobody knows where the dog was born. He first entered history in July 1917 as an ownerless tramp. Stubby appeared on the Yale University football field, which was the site of a camp where soldiers of the 102nd Infantry Regiment received basic training before deployment.

On a stuffy summer morning, as they later said in the news, Stubby wandered into a huge field where soldiers were doing exercises. He was unimpressive—short, barrel-shaped, a little plain, with brown and white stripes. But Stubby stayed in the camp. J. Robert Conroy, a 25-year-old private, formed the closest bond with the mongrel. The two soon became inseparable.

In September 1917, a few months after Stubby first joined the troops at Yale Stadium, the 102nd Company prepared to depart. Conroy was faced with a problem: what to do with the dog he had already named? Dogs were banned in the US military, but Conroy managed to keep a stray dog as a pet throughout his three-month training. Taking Stubby with us to Europe was a more difficult task.

The troops traveled by rail to the port of embarkation for soldiers bound for France. Here the division would board one of the largest cargo ships sailing the Atlantic. The New York Times describes how Conroy eluded the ship's guards by hiding Stubby in his army overcoat. Then he secretly took the dog into the hold and hid it in the coal compartment.

At some point, Stubby was discovered. The story goes that the dog won over the officers, who discovered him by raising his right paw in salute. It seems that this is a beautiful fairy tale, but the truth does not play a role here. By the time the troops were on the west coast of France, Stubby had become the unofficial mascot of the 102nd.

Dogs in war

The Persians, Greeks, Assyrians and Babylonians used dogs in battle. Dogs were part of Attila's troops during his European conquests. In the Middle Ages, knights equipped dogs with canine armor, and Napoleon used trained dogs as sentries in the French campaign in Egypt. In many countries that participated in the First World War, schools for training fighting dogs existed even before the conflict.

They preferred purebred dogs - some served as sentries, others hunted rats in the trenches, others delivered parcels, and others, like huskies, transported cargo. There were dogs in the Red Cross - they provided assistance to the wounded, carried water and medicine. Since they wore the symbol of the Red Cross, the enemy side tried not to shoot at them. Often dogs simply provided comfort and warmth to dying people on the battlefields.

Many dogs were heroes. In one battle, Prusko, a French dog, located and carried more than 100 wounded men to safety. In 1915, the French government asked Alexander Allan, a Scotsman living in Alaska, to provide his army with sled dogs. Heavy winter snows in the mountains held back French supply lines; mules and horses could not get through the mountains to transport artillery and ammunition.

Allan managed to smuggle over 400 sled dogs from Alaska to Quebec, where they boarded a cargo ship bound for France. Once there, the dogs carried ammunition, assisted soldiers in laying communication lines and in transporting wounded soldiers to field hospitals.

Germany had a long tradition of using service dogs and had the most trained canine units. In the 1870s, the German military began coordinating with local kennel clubs to train and breed fighting dogs. They founded the first military dog training school in 1884, and by the start of the war they had almost 7 trained dogs. At the height of the war, German canine troops numbered more than 000: messengers, orderlies, draft animals, guards.

Among the Allies, France had the largest and most diverse canine units. At one point, the US Army borrowed dogs trained in France for guard duty, but the plan was foiled because the dogs only responded to commands in French.

At the start of the war, the United States was one of the few participants in World War I that did not have trained dogs.

Stubby on the front line

In October 1917, a month after the landing in France, American troops entered the Western Front. Recruits from the 26th Division participated in four major offensives and 17 combat actions. They saw more combat than any other American infantry division in just 210 days.

Stubby was there the whole time. The regimental commander, Colonel John Henry Parker, was a gruff, intimidating man, a veteran of the Spanish-American War and a skilled machine gunner tactician who eventually received the Silver Star for heroism. It was Parker who gave special orders for Stubby to remain with the 26th Regiment.

The dog initially did not serve officially, but was allowed to stay with Conroy even when he went on a mission as a messenger. By February 1918, the 102nd Division was awaiting the start of the German offensive. On March 17, bells and horns rang - a signal of a poisonous gas attack. Within XNUMX hours, German gas shells rained down on the ground. Somehow the dog and his owner survived. Perhaps the gas masks helped. They were even put on dogs.

It was then that Stubby saved the 102nd from a gas attack. The Times describes how one morning, while most of the soldiers were asleep, the unit came under an early morning gas attack. Stubby first smelled the gas and then ran up and down the trenches, barking and biting the soldiers, trying to wake them up. On April 5, Stubby received his first military rank as a private.

The Americans soon relocated to the Sespre commune. The division headquarters was located near the dangerous place “Dead Man's Bend”. Before a dangerous turn there, oncoming cars had to slow down; this place became easy prey for German artillery. Stubby and company were placed in support positions to await the German breakthrough.

On April 20, German infantry carried out one of their first attacks against American forces. Almost 3 German soldiers opened fire on the small contingent of 000 Americans and routed them. Stubby received his first battle wound when a German shell fragment hit him in the left front paw.

However, by June Stubby had recovered and returned to duty. When the 102nd Division reached Chateau-Thierry in July, the dog learned to distinguish the soldiers' uniforms. He noticed the German.

In Argonne, Stubby sniffed out a lost German soldier hiding in nearby bushes. The dog gave chase, eventually dragging the soldier to his own. The Order of the Iron Cross, worn by the captured German, subsequently adorned Stubby's army "uniform".

Stubby later took part in the brutal offensives at Aisne-Marne and Champagne-Marne.

When the war ended, Stubby was in France. The demobilization process was delayed, and the troops remained there for several months after the truce. While waiting to return home from France, Stubby met his first of three presidents, Woodrow Wilson, on Christmas Day 1918. On April 29, 1919, Stubby and Conroy were discharged.

Stubby's life after the war

After the war, Stubby attended the 1920 Republican National Convention, which culminated in the nomination of Warren G. Harding. Harding officially welcomed Stubby into the White House in 1921. When Conroy went to study law at Georgetown, Stubby became the university's official mascot, the forerunner of the modern Hoya bulldog.

Stubby became a member of the Red Cross and the American Legion. The YMCA gave the dog a lifetime membership, noting that he is entitled to "three bones a day and a place to sleep" for the rest of his life.

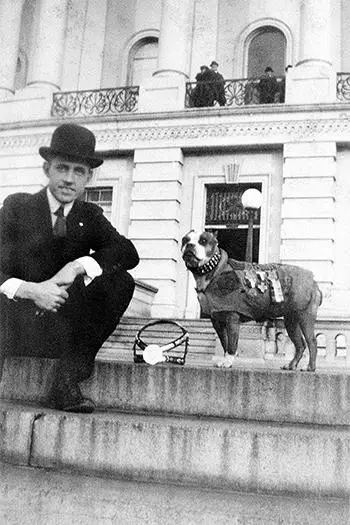

Stubby and Robert Conroy in front of the Capitol

The Military History Department of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History houses an astonishing artifact that testifies to Stubby's fame and the influence he had on American popular culture in the early post-war years. This is a leather bound scrapbook.

The book is filled with documents and letters from fans, poems, drawings, and an invitation to the White House from President Wilson. The documents and reports collected in Conroy's scrapbook outline Stubby's service history.

It is difficult to say whether Stubby's celebrity was fostered by the US government or spread on its own after the war. It is known that after World War I, Conroy worked as a bureaucrat, first in the Bureau of Investigation (the predecessor of the FBI), then in military intelligence and on Capitol Hill as a secretary to a congressman.

Not everyone loved the dog. Many military men did not understand such a stir around her. For example, one general wrote ironically:

Stubby died in his sleep in Conroy's arms in 1926.

Today he may be the last decorated World War I veteran to be seen in the flesh. His taxidermied remains are on display at the Smithsonian Institution alongside another famous World War I animal, a homing pigeon named Dear Friend.

Information