The evolution of sails on ships of the 18th century

Features of sail making

Before the advent of steam power in the 19th century, warships depended on the wind and their sails. It was the sails that provided sailing ships with motive power and the ability to maneuver in battle. It would seem that what could be simpler than a sail? I pulled on the rag and voila!

However, to function well, a sail must be strong enough (to withstand wind and damage) and light and flexible enough to be handled by sailors who do this work at altitude and often in difficult weather conditions.

And this balance, as it turned out, is very difficult to achieve, so in the 18th century the compromise solution was to use different types of canvas for different sails: lighter material was taken for sails of the second, third and fourth tier, and thicker and stronger material for lower tier sails.

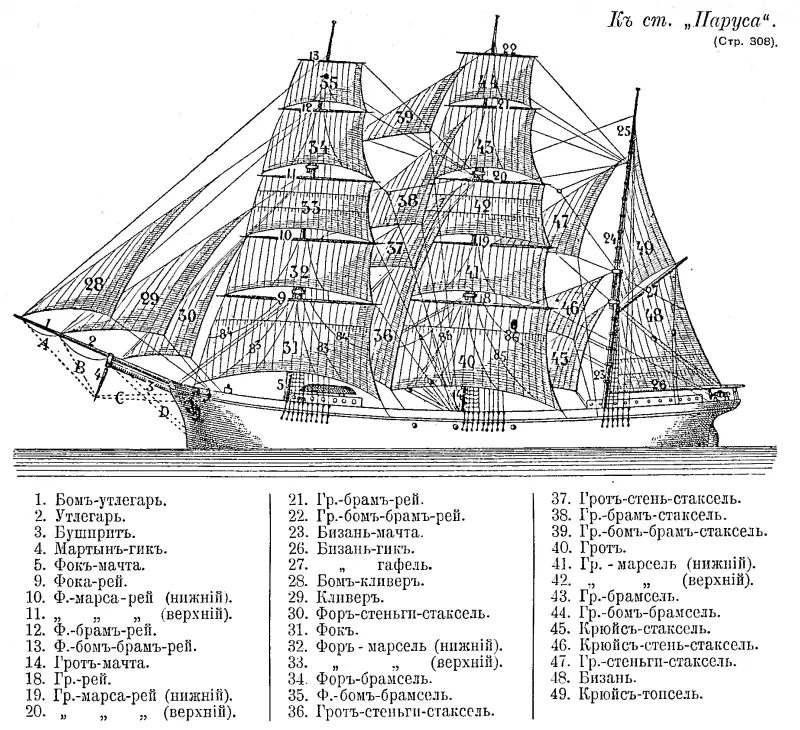

This drawing was used to illustrate the article “Sails”, published in the seventeenth volume of the “Military Encyclopedia”, which was published by the publishing partnership of I. D. Sytin in 1914 in the capital of the Russian Empire - the city of St. Petersburg.

Canvas in British navy was assessed by number. Number 1 canvas was the coarsest and heaviest, and number 8 was the thinnest and lightest. Heavier versions of canvas usually had a double warp, while lighter versions had a single warp.

Even the straight sail had a rather complex design. Initially, the sails were square or rectangular, but by the beginning of the 17th century they looked more like a trapezoid, since the eyelets and fastenings on the upper yard were shorter in length than on the lower yard. This was due to the introduction of more reliable rigging and lengthening of the yards. The luff is most often concave upward to better catch the wind.

At the edges, the canvas was bent in half and a lycrop was passed there, and it was shifted to the rear of the sail, so that on the darkest night the sailor could distinguish the front part of the fabric from the back by touch. The luff cable was thicker than the others.

The sail then needed to have grommets (holes) and centerboards (reef lines) to accommodate the reef bow (the horizontal stripe that allows reefing).

The edge of the sail. The lyctros and eyelets are clearly visible.

Thus, in the 74th century, it took more than a thousand man-hours to make one topsail for a XNUMX-gun ship of the line.

The sail goes out to the oceans

Before 1700, major naval powers operated their fleets in European waters during the summer months and were always close to friendly ports. Since firepower was crucial, the ships were loaded with guns and ammunition to the full - to the detriment of their handling and weather conditions.

But the rapidly growing colonial economy of the New World and the massive expansion of trade with Asia led to a change in strategic priorities. Naval power needed to be projected across the world's oceans using ships capable of operating in harsher weather conditions. Naval operations also changed, with greater emphasis placed on maneuvering the fleet to gain a tactical advantage over the enemy. As a result, warships and their sails had to adapt to these requirements.

And since we are talking about the adaptation of ships, we can also talk about the adaptation of sails. And it was at this time that staysails began to appear, that is, sails located between the masts. Their number only grew throughout the 18th century, because staysails were oblique sails and allowed the ship to take the wind more sharply, providing both tactical advantages in battle and greater safety in bad weather, especially when the ship was in strong winds.

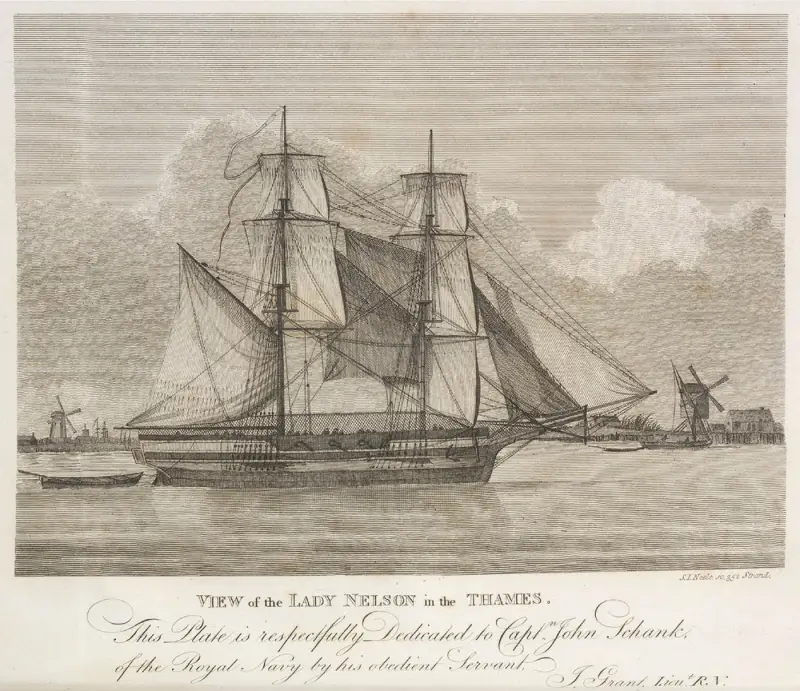

HMS Lady Nelson (1798) with staysails set.

The first staysails appeared in Royal Nevi in 1709 and until 1720 they were triangular, but after 1760 some staysails were also installed quadrangular. The staysail was initially placed on the stay between the mizzen and main masts and between the main and foremasts, and when the stays became too thick due to the enlargement of the rigging, a handrail was drawn along the stay.

As for the jib, it was used back in the 17th century on small ships, but it did not quickly enter the navy. The fact is that this sail is located on a separate rail, which could pass independently between the forestays, so an additional cable was sewn into its luff, since the jib was raised from the deck, and not from the bowsprit. Thus, the luff of the jib was like a continuation of the rail.

At the end of the 18th century, the jibs were placed on permanent rails to facilitate setting.

The most important for maneuvering were the bow sails, and they underwent the biggest changes.

Firstly, the further forward such sails are extended, the more, according to the rule of leverage, the ship will develop speed. At the beginning of the 18th century, sailing ships had a small vertical mast on the bowsprit, on which one or two straight sails (bomb blind) were placed, as well as a sail under the bowsprit (blind or spritsel). Together with a larger straight spritsel, these sails served to gain speed or could be a turning lever. However, most often the blind was used as a shunting sail, for harbors or for removing/anchoring. The absence of a large amount of rigging made it possible to place the yard almost vertically (the so-called heated blind), that is, in this position it worked like a jib.

HMS Prince (1670) in the wind. The blind and bomb blind are clearly visible.

But since such sailing equipment was both complex and limitedly effective, from 1705 blinds began to disappear, and gradually (this process dragged on for 20–25 years) they were replaced by jibs.

What, exactly, did they do? They lengthened the bowsprit and began to stretch triangular sails between it and the foremast, which made it easier to maneuver and easier to control than straight sails.

Of the main sails, the mizzen underwent the most changes. The advantages of having a lateen sail at the stern for maneuverability have long been known. This sail provided significant leverage when turning. And through the mizzen mast there was a ryu-ray going obliquely, on which a Latin-type sail was located.

HMS Woolwich (1677). The Latin mizzen on the ru-rey is clearly visible.

But it was inconvenient. When the ryu-ray was turned in one direction, the part of the sail that was on the other side of the mizzen mast prevented it from effectively making the turn. Therefore, from the 1730s, the ryu-ray was gradually shortened, and by the 1760s it did not cross the mast, but was now located only on one side, although, of course, its turning functions were preserved. However, the lateen sail still remained.

But by the time of the American War of Independence, the British began to replace the lateen mizzen with a trysail sail. They did it simply - instead of the ryu-ray, they installed two half-yards (a boom and a gaff), between which a gaff trysail was pulled. Gradually this innovation spread to almost all ships. As of 1798 - the year of the Battle of Aboukir - only HMS Vanguard retained the lateen sail on the mizzen and the ryu-ray crossing the mast.

HMS Indefatigable as part of Moore's force against Spanish frigates, 5 October 1804. The trysail on the mizzen is clearly visible.

By the way, the second such ship could have been HMS Alexander, but there would have been no luck, but misfortune helped - the ship was caught in a storm during the race for Napoleon, lost all its masts, and during repairs the mizzen on it was rebuilt using the latest method.

What were the sails made of?

Here it must be said that different materials were used in different countries. Initially, the main material for making sails was hemp, primarily because this material effectively resists salt water and almost does not rot. But there was also a significant drawback - hemp sails were very heavy, and it was very difficult for sailors to handle them. And the extra weight on the masts increased the value of the metacentric height, which threatened the ship with poor stability and capsizing.

Therefore, from about the 1730s, the British began to switch to sails made of flax, most often the flax was made in Russia.

As for the Russian fleet, almost all the rigging of Russian sailing ships, ropes, nets, flags, sails and even sailor uniforms, right down to the sailors’ uniforms, were made from hemp at that time. Each ship required 50–100 tons of hemp fiber for equipment every two years.

This state of affairs remained until Nicholas I, who transferred the Russian fleet to flax. That is why almost all history In the sailing fleet, the sails of Russian ships were a dirty yellow-green color - just the color of hemp fabric.

Don’t think that our ancestors were stupid - the usual savings took place: hemp canvas cost 7–8 rubles per pound, while linen canvas cost 16–22 rubles per pound, depending on the quality of the workmanship. It’s clear that priority in supplies and financing in Russia has always been given to the army, so they decided that the sailors could get by with hemp sails.

The Dutch and French used bleached linen canvas with a small admixture of hemp fibers to sew sails.

The Battle of Abukir, the English squadron attacks under sail.

The Spaniards saw flax as the main material for sails, but they additionally soaked it in special dyes and “primed” it so that the fabric could resist rotting and salt water.

The Americans were probably the first to make sails from cotton. No, initially they, like everyone else, made their sails from a mixture of flax and hemp. But in the 1830s they started thinking. Cotton as a material is good for everyone - light, soft. One problem - it doesn't last long. And following the example of the French, they began to impregnate cotton with linseed oil. Soon linseed oil was replaced with resin - and it turned out that cotton was quite suitable as canvas. At the same time, sails made from it, with the same strength, are lighter than linen and hemp. And starting around the 1840s, the American fleet began sailing with cotton sails.

Sailing ship speeds

It would be interesting to see what the evolution of sails gave sailing ships. But how can we determine this? Let's try the simplest parameter - speed. Yes, this is a little wrong, because the shape of the hull, the sheathing of the bottom with copper sheets, and the ratio of length to width influenced it, but nevertheless...

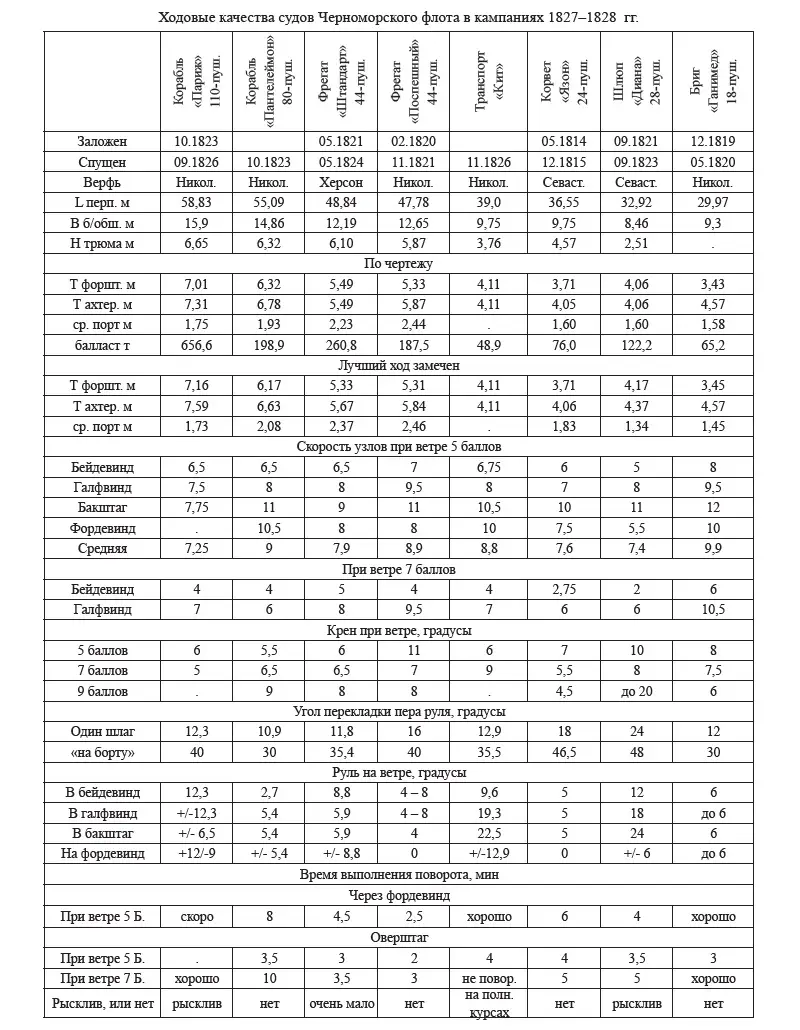

So, according to Morgan Kelly's article "The Speed of Sailing Ships during the Early Industrial Revolution, 1750–1830," the speed of ships on passages increased from 3–4 knots in the 1750s to 6–7 knots in the 1820s–1830s. It wouldn't seem like much, right?

But peak speeds when jibe or backstay almost doubled. In the 1730s, the standard speed of a battleship in fresh wind was 5–6 knots, in the 1800s it was 8–9 knots. Frigates, instead of 6–7 knots (the usual speed in a good wind at the beginning of the century), began to develop up to 12–14 knots (for example, USS Constitution and HMS Endymion).

And finally, for an example of the speed of some ships of the Black Sea Fleet during the 1820s (from the article by A. M. Glebov “Analysis of the propulsion, stability and controllability of ships of the Black Sea Fleet during the Russian-Turkish War of 1828–1829 based on archival data”).

References:

1. Philip K. Allan “Upon the Malabar Coast” – Independently published, 2021.

2. A. M. Glebov “Analysis of the propulsion, stability and controllability of ships of the Black Sea Fleet during the Russian-Turkish War of 1828–1829.” based on archival data" - News of Altai State University, 2012.

3. Morgan Kelly and Cormac Ó Gráda “Speed under Sail during the Early Industrial Revolution (c. 1750–1830)” – UCD Center for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP14/10, University College Dublin, UCD School of Economics, Dublin.

4. Robert Kipping “The Elements of Sailmaking: Being a Complete Treatise on Cutting-out Sails, According to the Most Approved Methods in the Merchant Service” - FW Norie & Wilson, 1847.

5. David Steel “The Elements and Practice of Rigging And Seamanship” – David Steel: London, 1794.

Information