Journey to the ancestors. Russians in Egypt

The Polish film “Pharaoh” (1965) can rightfully be considered one of the best films about Ancient Egypt...

A mystery at all times

Your shine will be drunk by the pharaohs,

The treasury was destroyed by enemies.

Culture, and that too was stolen,

The centuries-old works were burned,

The leading people were exterminated,

And they couldn’t calm down the anger.Mikhail Galkin "To the Vanished People"

History and people. Who among us has not heard about “Walking across Three Seas” by Afanasy Nikitin, the first explorer and traveler, the author of wonderful notes. But we also had other explorers who visited not India and Persia, but Egypt, and they also wrote their own “Walks...” about this.

The history of the great Egyptian civilization, which dates back 27 centuries, is one of the mysteries that always interests our readers. Although there is probably no more meaningless topic if we look at it from the point of view of common sense. However... it's interesting.

And if people are interested in something, it means it is needed, it is in demand. Here is today's story, we will again dedicate it to Egypt, and we will report on how the inhabitants of Russia in distant, distant times became acquainted with its culture, how they learned about it, and which Russian was the first to visit this country. And, of course, we will also talk about what written works he left us as a legacy...

The embassy of Ivan the Terrible goes to the East

The first of the Russian tsars to send a special embassy to the East was Tsar Ivan the Terrible. Why he needed this is difficult to say. Perhaps simple curiosity, or maybe some kind of state interest.

The important thing is that the envoys included a merchant from Smolensk, whose name was Vasily Poznyakov. The mission of the embassy was to represent the royal personage in overseas lands and “to write down the customs in those countries.”

The result of that journey was the book: “The Walk of the Merchant Vasily Poznyakov” - the first book in Russia that told Russian people about Egypt.

Faience amulet of Ra-Horakti, only 2,8 cm high. 664–630. BC e. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The embassy left Moscow “in the summer of 7066” (“from the creation of the world,” that is, in 1558 according to our account) and moved in a roundabout way through Lithuania “to Constantinople,” and from there to Alexandria, and it got there only a year later!

But the ambassadors were in Cairo for only four days. After this they returned to Alexandria and then went to the Sinai Peninsula.

The goddess Tauret, who was the patroness of women in labor. Height 5 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Poznyakov spent very little time in Egypt, but this was enough for him to be able to talk about the conquest of Egypt by the Turks, its cities and nature in “Walking”:

Alabaster bowl. Dynasty II, c. 2750–2649 BC e. Saqqara, tomb 2322: Egyptian Antiquities Service/Kybella excavations, 1910–1911. Material: travertine (Egyptian alabaster). Height 9,4 cm; diameter 23,6 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

"Bestseller of the XNUMXth century"

In Russia, for some reason, Poznyakov’s book began to be attributed to the merchant Trifon Korobeinikov, who also visited Egypt, but 25 years after Poznyakov. He simply added several of his chapters to Pozdnyakov’s book.

It has come down to us in more than two hundred (!) handwritten copies, and in another forty printed books. Which once again speaks of the great interest the Russians of that time showed in Egypt and its antiquities!

Another vessel made of alabaster. New Kingdom, XVIII Dynasty, c. 1550–1458 BC e. Upper Egypt, Thebes, courtyard CC 41, pit 3, burial B 4, between coffin head and wall, MMA excavations, 1915–1916. Dimensions: height 13,6 cm; diameter 11,6 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Only 300 years later it was possible to find out that “Korobeinikov’s Travels” is nothing more than Poznyakov’s work with Korobeinikov’s additions. Moreover, six handwritten copies of his “Walkings” have been preserved, so you can easily compare who exactly wrote what. Korobeinikov was also the first to describe the African ostrich to the Russians, and he found very funny comparisons for this.

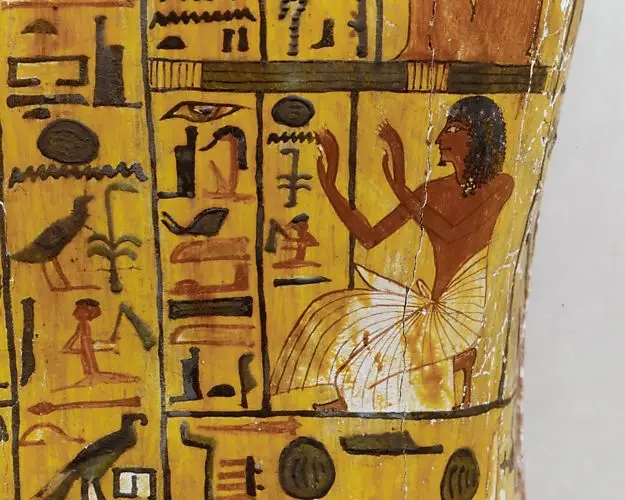

Sarcophagus of the mummy of Iineferti. New kingdom. XIX dynasty. The era of the reign of Ramesses II. OK. 1279–1213 BC e. The sarcophagus was closed with a wooden lid (“mummy board”), on which a figure of the deceased or deceased was carved, and it was carved and painted so as to show the deceased in a long white dress with folds. Upper Egypt, Thebes, Deir el-Medina, Tomb of Sennejem, Egyptian Antiquities Service/Maspero excavations, 1885–1886. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Then the Kazan merchant Vasily Yakovlev, nicknamed “Loon,” went to Egypt and stayed there for 14 weeks. Apparently, that’s why he wrote more than his predecessors.

Upper part of the lid of the sarcophagus of Iineferti's mummy. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Travel of Vasily Yakovlev

In 1634, he began his journey, going from Kazan to Astrakhan, and then to Tiflis, and then to Erzurum, Jerusalem, and in this indirect way finally reached Egypt. As we walked, I wrote down everything I saw. For example, he was the first to describe the obelisk from Heliopolis, “12 fathoms” high (about 25 meters high), indicating that it had “the name of the pharaoh.”

It’s funny that the not-so-educated merchant clearly indicated that the signs on the obelisk were writing. Whereas the German professor Witte, more than a hundred years later, argued that Egyptian obelisks are nothing more than “creations of nature,” but the inscriptions on them were allegedly “carved” by special snails!

In the tomb of Ineferti they found such a figurine of ushabti. The word ushebti can be translated as “I am here!” That is, this is a figurine that is a substitute for its owner, which came to life in the next world and, by order of the gods, had to work together with him. And if you had 365 ushabti available, then you didn’t have to worry about anything else! It is made from Nile silt and then dried in the sun. But even today, modern Egyptians make the same ushabti from Nile silt in the same way and sell them to tourists, not without profit. It’s just that their molds are made of vixint. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gagara also reached the pyramids in Giza, and they made a very strong impression on him. He also saw a crocodile on the Nile, about which he spoke as follows:

Interestingly, this is the very first description of a crocodile in our literature!

Sarcophagus of Khonsu. New kingdom. XIX dynasty. The era of the reign of Ramesses II. OK. 1279–1213 BC e. Height 188 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Alexey Mikhailovich the Quietest sends his embassy...

Once again, an embassy to the eastern countries “according to the sovereign Tsarev and Grand Duke Alexei Mikhailovich of All Rus'’s decree” was sent on June 10, 1649. Among those sent was a certain Arseny Sukhanov - one of the poor small-scale nobles, impoverished and so busy “dragging between the courtyard on Tula.” But he was extremely literate and not only understood literacy, but also knew Greek, both ancient and living, spoken. He knew Polish and even understood a little Latin. He was on the road for ten years on various diplomatic affairs, visiting Georgia, Moldova, Asia Minor, as well as Mesopotamia and Palestine, Greece and Egypt.

Hieroglyphic inscription on the sarcophagus of Khonsu. New kingdom. XIX dynasty. The era of the reign of Ramesses II. OK. 1279–1213 BC e. Height 188 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is interesting that he had considerable sums with him, entrusted to him for the purchase of all sorts of Greek books... drawing sheets from different lands.

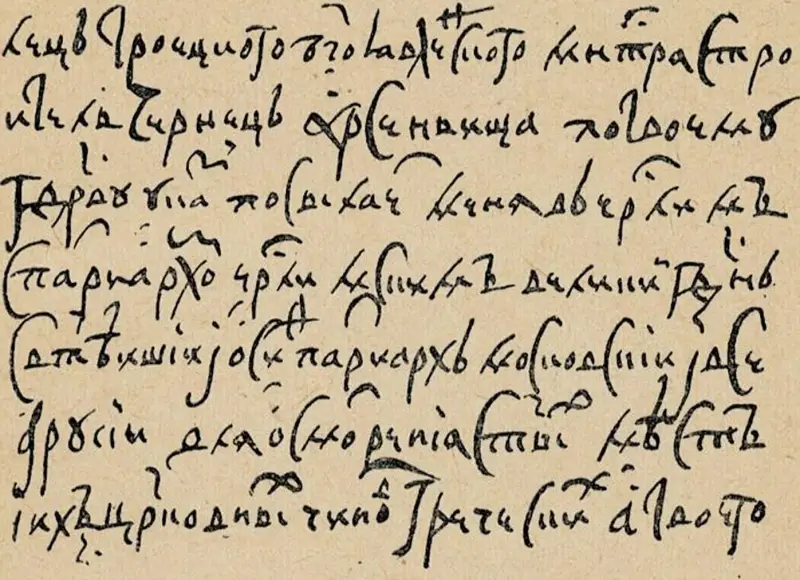

Leaving for the East, Sukhanov submitted a petition to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich on May 9, 1649, asking him to give him money for the trip. Illustration from the book by N. Petrovsky and A. Belov. Country of Big Hapi. Leningrad. Detlit. 1955, p. 21.

Sukhanov stayed on the banks of the Nile for a month and a half and described in great detail everything he saw.

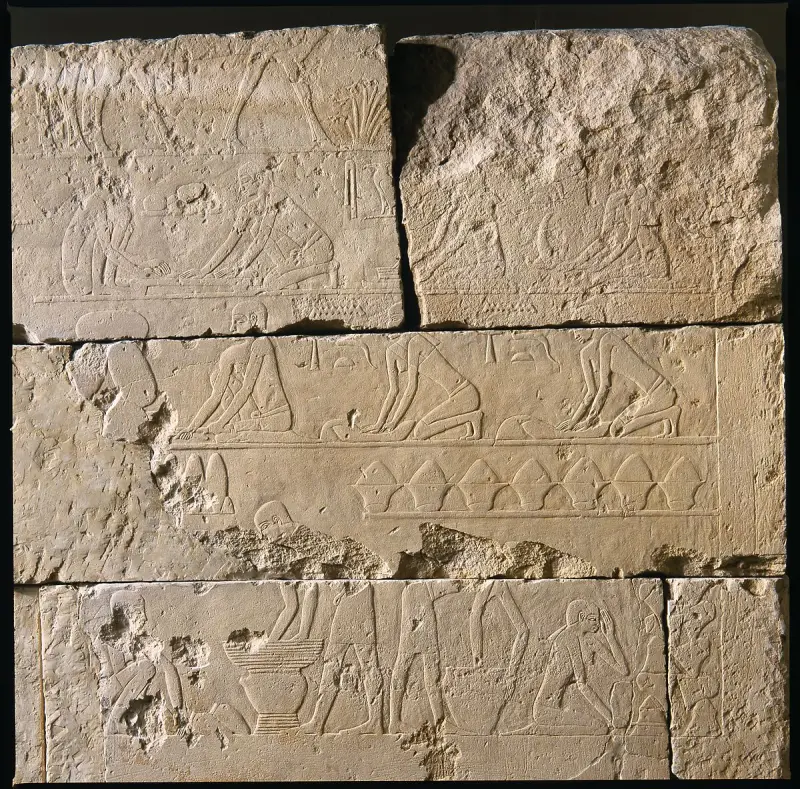

Interior of Raemkaya's mastaba. Ancient kingdom. V Dynasty. OK. 2446–2389 BC e. Saqqara. The mastaba itself is located north of the Pyramid of Djoser, Egyptian Antiquities Service/Cybella Excavations, 1907–1908. Raemkai's Mastaba was originally built and decorated for an official named Neferiretnes, whose name and titles can still be seen on the false door. Either Neferiretnes fell out of favor, or his entire family died, so there was no one to ensure that he was buried “as it should be.” And note that the use of this tomb for Raemkai could not be a squatter. It was probably carried out by decree of the pharaoh around 2381 BC. e. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

And these are the bas-reliefs of its northern wall. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sukhanov wrote that “before this, no one from Moscow had been here, but only under Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich there was an ambassador,” that is, he knew about Poznyakov’s embassy. But he most likely knew nothing about Vasily Gagara’s journey, because he traveled at his own peril and risk.

Painted figures on a bas-relief from the Raemkai mastaba. The inscriptions call Raemkai (the name means “the sun is my life force”) “the bodily son of the pharaoh,” so he may indeed have been the pharaoh’s son (bastard) and prince. True, we do not know exactly which pharaoh was his father. One title indicates his connection with coronation ceremonies, meaning Raemkaya was sometimes quite close to the personality of the pharaoh. The tomb is decorated with many beautiful reliefs with scenes of catching birds, cutting meat, baking bread and brewing beer, as well as hunting in the steppe with a lasso and dogs. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

He wrote about the pyramids in the vicinity of Cairo:

True, he named only three pyramids, in Giza, but he simply did not know that there were more than 118 pyramids in Egypt!

Sukhanov's trip to Egypt turned out to be very useful, both for the state and for the traveler himself, because after him Sukhanov was put in charge of the Moscow Printing House, and this position was both prestigious and responsible.

Information