The brief brilliance of the Italian Lightning

This article is dedicated to the French commander Gaston de Foix, Duke of Nemur. Why him? On the one hand, because he deserves it. It is safe to say that in terms of his talents he was not inferior to his more famous colleagues in the profession, such as the Great Condé or Turenne. On the other hand, it is widely known only in narrow circles, and even then - thanks to the only battle that is described in detail in all books on military stories (and who would have known about Conde if he had died at Rocroi). Indeed, Gaston's military career lasted only a few months, so it can be described in one not too long article.

First, as expected, some biographical information. Gaston de Foix, Duke of Nemours, Comte d'Etampes and Viscount of Narbonne, Peer of France, etc., was born December 10, 1489. His father was Jean de Foix from the house of Foix-Grailly, and his mother was Marie d'Orléans, sister of King Louis XII.

It is clear that with such a pedigree it was difficult not to make a military career, but, as it later turned out, talent, energy and courage were added to the origin. Gaston participated in all Italian campaigns, starting with the suppression of the Genoese rebellion in April 1507 (the Republic of Genoa and the Duchy of Milan were captured by the French at that time). At the same time, he was appointed governor of the province of Dauphiné, but did not make any mark in this position.

Map of Italy at the beginning of the Italian Wars

As follows from the nickname of the hero of the article, he fought in Italy, where at that time the next, third or fourth of the Italian wars was going on - the so-called. the war of the Holy League (there was nothing sacred, of course, in this league). Sometimes this war is considered part of the war of the League of Cambrai, sometimes it is separated into a separate one - hence the discrepancies.

It was a very interesting time, when chivalry, its ideals and traditions still existed, but they were already being replaced with might and main by mercenaries with their morality, or rather, its complete absence. Yesterday's allies became the worst enemies and vice versa, so Machiavelli was only describing the existing reality. France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and, to the best of their ability, the Italians themselves, i.e. the Venetian Republic, the papal state and the small northern Italian duchies, took part in the fight for the richest Italian lands.

I will not describe all the intricacies of the then policy and its continuation, that is, the war; it is enough to point out that at the time Gaston de Foix appeared in Italy, the French king found himself in isolation. France was opposed by Spain, Pope Julius II, Venice and even the Swiss, who usually fought under its banner. The only ally was the Florentine Republic and the Duke of Ferrara Alfonso d'Este, a great connoisseur and enthusiast of artillery, but clearly not a figure who could seriously influence the course of the war.

Portrait of Alfonso d'Este by Titian

So, in October 1511, Gaston de Foix arrived in Milan as governor of the duchy and commander of the French army. His first task was to repel the advance of the Swiss, who formally acted at the call of Pope Julius II, but actually for the first time decided to play their own game and place their puppet on the throne of the ruler of Milan [1].

In fact, the allies, i.e. the Spaniards, the British and the Italians, planned simultaneous attacks on France and its Italian possessions, but, as is usually the case with the allies, synchronization did not work out, and in late November - early December only the Swiss launched an offensive. Nevertheless, this was a very serious threat, since the Swiss were considered the best European soldiers, and even the defeat at Cerignola in 1503 did not shake this reputation. Moreover, the army was quite large - more than 15 thousand infantry [3], however, without cavalry and artillery - they were usually supplied by the allies.

Now it is difficult to say exactly how this attack was repelled; what is certain is that there were no major battles. According to some sources, Gaston, avoiding battle, collected all the supplies in several strong points and attacked Swiss foragers in small detachments [3], according to others, he offered to give battle where it was beneficial to him, but the Swiss refused [4], according to others - King Louis XII simply bought them up [13]. The latter, of course, is possible, but rather as an additional incentive to leave the inhospitable duchy. Be that as it may, without supplies and without waiting for the allies, at the end of December the Swiss returned to the south of Switzerland.

Meanwhile, in January 1512, the Spaniards of the Neapolitan Viceroy Don Raimondo de Cardona (the south of Italy belonged to them since 1504) and the papal troops became more active. In May of the previous year, the French captured Bologna, which belonged to the papal state. Now the Holy Father decided to recapture the city with Spanish help.

At the same time, Venetian troops concentrated opposite Brescia and Bergamo. These cities were also captured by the French, but before that they were part of the Venetian Republic, and retained significant autonomy, thanks to which the majority of residents sympathized with it, that is, Venice.

Raimondo de Cardona

On January 26, Don Raimondo, with an army of 20 thousand, consisting approximately equally of Spaniards and Italians, began the siege of Bologna. The siege activity was directly led by Don Pedro de Navarro, the best engineer of that time. He placed a powder mine under the city wall and detonated it. However, despite the terrible roar and smoke, the wall did not collapse.

Residents of Bologna attributed this to a miracle created by the Madonna, and the French to a well dug over a mine gallery (it was discovered with the help of seemingly children's toys - bells and rattles) [6]. In full accordance with the laws of physics, the energy of the explosion went along the line of least resistance. It was probably the French who were right. By the way, the first known case of mine action.

Although the assault launched by the Allies on February 1 was repulsed, it is unlikely that the garrison of two thousand could resist for long. However, on February 5, under the walls of Bologna, a French army unexpectedly appeared for the allies - 1 copies, i.e., about 300 thousand cavalry, 5 landsknechts and 6 French and Italian infantry [000].

The soldiers had to march for several days on forced marches along wet roads, in rain and snow - that year the winter was harsh, of course, by Italian standards. At dawn, taking advantage of the snowfall, the entire army entered the city undetected, fortunately it was not completely surrounded - Cardona blocked the northern and eastern directions, that is, the routes from Milan and Florence, but Gaston de Foix bypassed the city and passed through the western gate. There is probably no need to clarify that such a march is easy to carry out only on paper.

Having discovered this event, the Viceroy lifted the siege and went east to the town of Imola. At the same time, he had to leave most of the siege park and convoy [3].

However, for the French this was only the beginning of the campaign. In early February, the cities of Brescia, Bergamo and several smaller towns rebelled. Of course, these were not spontaneous protests by the broad masses. There is quite a bit of information regarding the events in Bergamo, but regarding Brescia it is known that the conspirators coordinated their actions with the commander of a limited contingent of Venetian troops (according to sources [14] - 3 thousand cavalry and the same amount of infantry) Andrea Gritti and on the night of February 2-3 They opened the gates for him.

The French garrison and local French supporters (who succeeded, of course) retreated to a castle located on Chidneo Hill outside the city. The castle was immediately besieged, but the new allies did not storm it. Either they didn’t dare, because from 500 to 800 [14] French soldiers had gathered there, or because they were busy with a more important matter - they began to settle scores with French supporters, which was accompanied by inevitable robbery.

Severe Gritti in the portrait of the same Titian.

Having learned about the events in Brescia, after a short (less than 72 hours) rest, Gaston went back to Brescia. True, he had to strengthen the garrison in Bologna in case Cardona returned, leaving 3 or 5 thousand [3] soldiers there. Instead of going northwest, directly to Brescia, he first went north to intercept the Venetian detachment. He succeeded on February 11, but the details of the battle vary greatly between sources.

However, contradictions in sources are the norm rather than the exception. The Italian Wikipedia [4] writes that the battle took place near Isolla della Scala, Gaston de Foix had 700 gendarmes and 3 thousand infantry, the Venetians had 300 men-at-arms, 400 cavalrymen (as far as one can understand, these were stradiots - light cavalry from Albanians in Venetian service) and 12 infantry. Of course, the last figure raises very serious doubts. Moreover, the losses of the Italians, according to the same source, were only 000 people and 300 guns.

Sytin's military encyclopedia [5] writes that there were only 3 thousand Venetians, and Gaston himself did not participate in the battle; one knight managed there without fear or reproach, that is, the Chevalier de Bayard and his detachment. Apparently, the sudden attack of the French knights scattered the Venetians, and they did not offer serious resistance. For the French, the main thing was that after the battle the Venetians did not go to Brescia, but directly in the opposite direction.

Pierre Terray de Bayar

Be that as it may, having covered 9 kilometers in 215 days, on February 17 the French army appeared at the walls of Brescia, although Gaston de Foix himself and the vanguard arrived a day earlier.

Of course, it is now difficult for us to appreciate how outstanding this achievement is, but it impressed contemporaries. In fact, it was precisely for this speed of movement that he received his nickname. It is assumed that at that time he had about 12 thousand people [4] or in any case no more than 15 thousand.

For the inhabitants of Brescia, the appearance of the French was a bolt from the blue, since Gritti fed them tales that Cardona had captured Bologna, and the French were defeated and fleeing. Therefore, there was practically no preparation for the siege, as well as no attempts to storm the castle; Apparently they wanted to starve him out.

In principle, there were more than enough defenders of Brescia - Italian sources [4] claim that the Venetian detachment alone consisted of 500 men-at-arms, 800 cavalrymen (apparently stradiots) and 8 thousand infantrymen, Carlo Pasero [14] counted more than 9 thousand people, entered Brescia on the night of February 2-3.

In addition to the mercenaries, there were many militias and volunteers from other cities in the city. For example, the head of the conspiracy, Count Avogadro, had his own “guard” of one and a half thousand highlanders from Val Trompia. However, most of the troops were outside the walls of Brescia: either blockading the castle, or were even further away - at the monastery of San Fiorano, a few kilometers from the city.

On the night of February 17, the French, in pouring rain, climbed Mount Maddalena, captured the monastery of San Fiorano and killed a thousand highlanders who were there. After this, Gaston sent reinforcements to the castle - 400 dismounted gendarmes and 3 thousand infantry [4]. Many sources say that due to the soggy ground, de Foix ordered the soldiers to take off their shoes. But, probably, we were talking only about knightly sabatons. And when he gave the order—that night or during subsequent attacks—is also unclear.

Now the castle became a stronghold for the subsequent assault on the city. However, according to the article Il sacco di Brescia di cinquecento anni fa [9], reinforcements were sent to the castle only on February 18, after the French army had surrounded the city and cleared its surroundings.

On February 18, Gaston de Foix sent an offer to the defenders of the city to surrender and open the gates. Everyone, except the Venetian garrison, was guaranteed life and safety, both themselves and their property. However, the residents of Brescia rejected the offer. According to other information, Gritty intercepted the letter and refused their name [3]. He only accelerated the digging of a ditch with a rampart in front of the San Nazaro gate opposite the castle. It was there that his most combat-ready troops were located.

The next morning the French attack began. As far as we can tell, they didn't have to climb the walls. They stormed the earthen rampart and, despite losses (Bayar was wounded there), managed to take it. After this, pursuing the retreating Italians, the French burst into the city. True, there is such evidence - the Storming of Brescia in 1512 shows good cooperation with the arrows: 500 dismounted gendarmes crouched down, the arquebusiers fired a general volley, and then, through the clouds of smoke, the French knights and infantrymen rushed into the gap, where the bullets thoroughly thinned out the party greeting the guests. [15]

Perhaps this is an inaccurate translation and meant a gap in the earthen rampart [9].

Be that as it may, the French managed to enter the city. What happened next was a matter of technique. The French, led by the Duke himself, reached the city center with street fighting, after which all resistance was suppressed. Part of the garrison, led by Gritti and Avogadro, tried to break out of the city gates, but the French gendarmes drove them back. Both Gritti and Avogadro were captured, but their fates were different - the first was sent to France, and Count Avogadro and his sons were executed in the city square.

It is assumed that the Venetian garrison was almost completely destroyed, as were most of the other defenders of the city. The French also suffered losses, Italian sources give a fantastic figure - 5 thousand people [4], but it also clarifies that, according to other sources, French losses amounted to only 100 people killed. Among the wounded, besides Bayard, there was another commander, Jacques de la Palis. Nevertheless, the French suffered unexpected losses, but more on that later.

Gaston de Foix, on pain of death, forbade the plunder of the city until the end of the fighting. But only then his soldiers turned around. In fact, the immutable law of war stated that a city taken by storm was subject to unconditional plunder. What was new was only the ruthlessness and scale of the process.

According to various sources, from 8 to 20 thousand people were killed on the streets of the city. True, no uniform existed then, and it was very difficult to understand where the soldier was, who threw away his helmet and pike, and where the peaceful man in the street was. French historians specified that all those killed were men; it was true - women were only raped.

French sources also stated that it was not the French who distinguished themselves in the atrocities, but the German Landsknechts and Gascon mercenaries, but this made no difference to the Brescians. As for the robbery, Italian sources mention that only one house remained unrobbed - where the wounded Bayard was brought in.

Desertion was an unpleasant surprise for the French commanders - many soldiers decided that they could return home as wealthy people, and there was no longer any need to risk their lives. It is interesting that even Italian historians did not particularly blame de Foix himself - he offered to surrender, the rest did not depend on him.

The robbery lasted 5 days, another 3 were required to remove the corpses from the streets. After this, the army headed towards Bergamo. Its residents already knew what happened in Brescia and opened the gates, paying off the French with a rather large sum of 60 thousand ducats (a wealthy Venetian lived on 15–20 ducats during the year, and the richest Duchy of Milan brought 700 thousand ducats annual income). Then, leaving garrisons in the pacified cities, Gaston de Foix returned to Naples.

However, neither he nor the army had to rest for long. The attack on France from different directions became more and more obvious. Moreover, the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian was preparing to join the English and Spanish kings. The latter even ordered the Landsknechts to leave the French camp and go to Germany. Another thing is that their commander Jacob from Ems (or Empser), who sympathized with Gaston, shelved the order.

Under these conditions, King Louis XII ordered Gaston de Foix to act offensively and as quickly as possible in order to defeat at least some of the allies and force them to a peace beneficial to France. Then send part of the army to France. Accordingly, the Spanish king gave his Neapolitan governor exactly the opposite instructions - to avoid battles and play for time.

Having recruited new mercenaries (the Bergamo money came in handy here) and preparing a new offensive, Gaston de Foix arrived in Ferrara at the end of March 1512, where his army was reinforced by local infantry, and most importantly - 24 cannons, which brought the number of cannons to 54, more than significant quantity for those years. Equally important, the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso d'Este, knew how to use them better than anyone in Europe.

The French army's first target was Ravenna, a city in Romagna captured by papal forces from Venice only a few years earlier. It was a fairly large city with its own port. What is more important is the last stronghold in Romagna, which still remained under the control of the papal state and provided a connection with Venice. Therefore, the pope urgently asked Cardona to prevent the city from being captured by the French. In turn, Gaston de Foix hoped to either take the city and move towards Rome, or provoke the Spaniards into a decisive battle.

On April 9, Gaston de Foix's cannons began to fire at the medieval walls of Ravenna, that is, high and relatively thin, and quite quickly made gaps sufficient for an assault. Cardona managed to send reinforcements to the city, so the assault carried out the next day was repulsed. Nevertheless, it was clear to everyone that without the arrival of the Spanish army the city was doomed.

Realizing this, Cardona, together with the papal troops, moved north towards Ravenna. On the same April 9, the Allies left Forli, a town located 30 km south of Ravenna and moved along the right bank of the Ronco (Roncho) River. The very next day they arrived in the village of Molinaccio near Ravenna. Now the two enemy armies were separated only by a river and one mile of distance.

Cardona had no intention of attacking the French; on the contrary, he urgently began to build a fortified camp on the banks of the Ronco. The idea was to create a threat to the French army, prevent it from conducting a full-fledged siege (for a siege it was necessary to surround the city, that is, disperse) and cut off the supply of supplies. By the way, the Venetian allies have already intercepted one food convoy [3]. Therefore, on April 10, at a military council in de Foix’s tent, it was decided to attack Cardona’s army the next day.

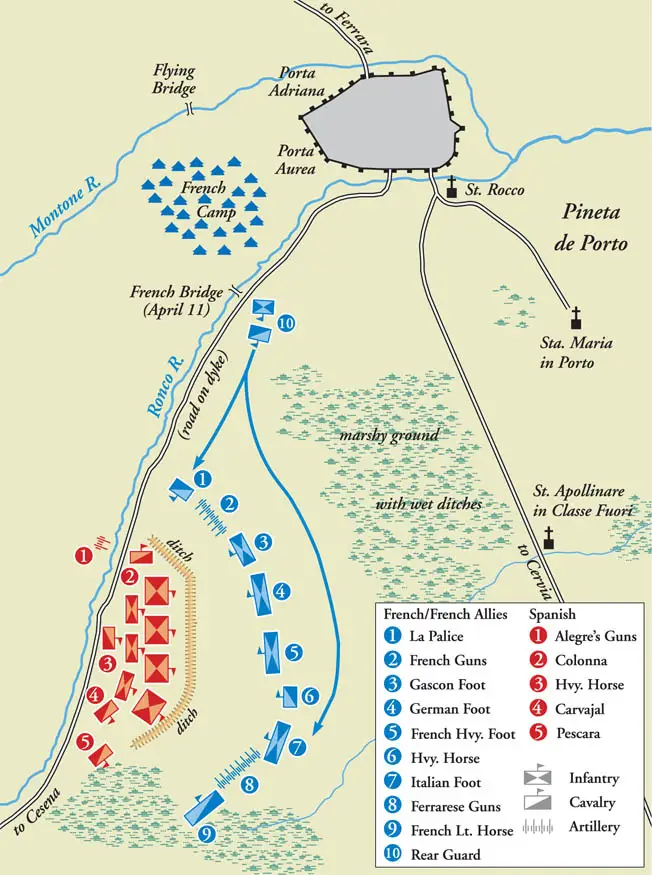

Quite a lot has been written about the Battle of Ravenna on April 11, 1512 and, despite the inevitable discrepancies, the descriptions are basically the same. The discrepancies generally concern the number of individual units and their location on the ground. It is known that the French, or more precisely, the Franco-Italian army numbered 23 thousand with 50 or 54 guns (although Italian sources reduce their number to 40 [17]).

By all estimates, there were about 18 thousand infantry, consisting of German, Gascon, French and Italian contingents. The most combat-ready of them were the German Landsknechts from the southern German lands. They were formed in the image and likeness of the Swiss infantry and, like the latter, were armed with long pikes and formed in deep columns.

Usually their number is determined at 5 thousand, although sometimes the figure varies from 4 [17] to 8,5–9 thousand [1]. There were probably about 5 thousand Italians, the rest were Gascons and French. Sometimes they write not about the French, but about the Picardy infantry, but they probably included mercenaries from all French provinces.

Interestingly, the Gascons still used crossbows rather than arquebuses like the Spaniards. Even the French did not rate their infantry too highly and, whenever possible, tried to replace it with the Swiss or Landsknechts; the Italian infantry was not much different from it. The Gascons were better, one French commander expressed this in numbers - 9 Gascons are worth 20 French, but they did not reach the level of the Swiss, Landsknechts and Spaniards.

There were about 5 thousand cavalry, of which more than 1 were gendarmes, undoubtedly the best heavy cavalry in Europe. The gendarmes equipped themselves at their own expense and did not skimp on armor and horses, but received salaries from the royal treasury, and therefore were more disciplined than the medieval Arjerban.

Scheme of the Battle of Ravenna from an article by William Welch

The Spanish-Papal army is estimated at 16–17 thousand people with 24 [17] or 30 [1] guns. According to almost all sources, there were 10 thousand Spanish infantry, many of whom were veterans who had fought with the Great Captain Gonzalo de Cordoba. The Spanish infantry had not yet become the best in the world, but was quickly moving in that direction.

Organizationally, it consisted of permanent colunellas (the famous tercios appeared later) numbering 1–000 people. Its interesting feature was the presence, in addition to arquebusiers and pikemen (their ratio was 1 to 300), rodeleros - infantrymen armed with a sword and shield. Later, rodeleros ceased to be used in Europe, but it was in this battle that they came in very handy.

There were 3-4 thousand papal infantry, about 1 horsemen, heavy cavalry, and the same number of jinetes - Spanish light cavalry. Only William Welch [500] writes that there were 3 thousand infantry, of which 10–8 thousand were Spanish and 9 thousand cavalry.

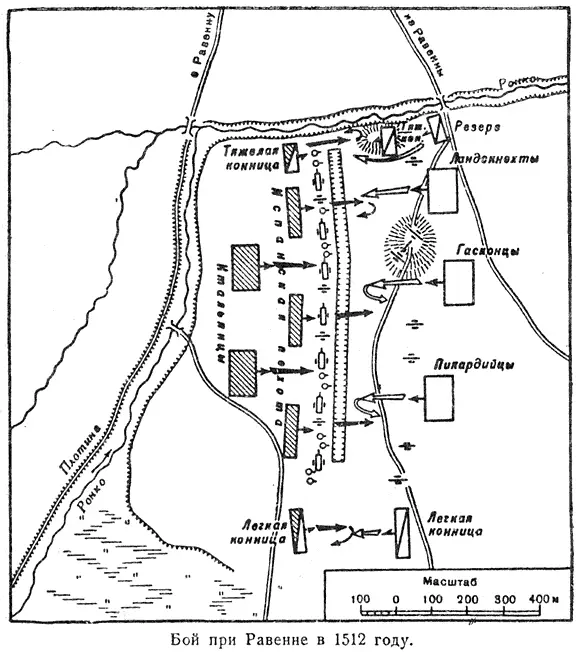

And this is a diagram from Svechin’s military history. It is clear that the difference is significant

The position chosen by Don Pedro de Navarro was almost impregnable - despite all the differences in the sources, it is clear that it was impossible to outflank it. The Spaniards' front, less than a kilometer long, was reinforced by a ditch, behind which there were carts with culverins and heavy fortress arquebuses (there were about 200 of them [18]), riflemen and field guns were placed between them, and behind them were infantry in the center and cavalry on the flanks.

On both sides, gaps were left between the ditch and the river for a possible cavalry counterattack. However, this position also had a drawback - a rather long distance to the city. Apparently, therefore, there was no interaction with the garrison of Ravenna, which numbered 5 thousand people [1], but did not even try to make a sortie.

From Welch's article. I don’t even know how real such a structure is.

Before the battle, Gaston de Foix, quite in the spirit of knighthood, challenged Cardona to a duel. He accepted the challenge, but did not leave the fortifications. Gaston also compiled a written disposition for his troops for the first time in history; Apparently, it has not been preserved, otherwise historians would have had less controversy. At night, French sappers built a pontoon bridge across Ronco, and in the morning the entire army crossed unhindered and moved towards the Spanish camp. Cardona did not want to leave advantageous positions and refused the offer to attack the enemy at the crossing, although the distance from the camp to the bridge was a little more than half a kilometer.

By mid-morning, the French army deployed into battle formation opposite the Spanish camp. It was fairly standard - infantry in the center, cavalry on the flanks and a reserve that could be used against a garrison attack. It is difficult to say more specifically, since each source draws its own diagrams, but it is clear that the landsknechts were located in the center.

It is not known how the French placed the guns at the beginning of the battle: according to some sources, evenly in front of the front, according to others, to the left and right of the infantry. Moreover, it is unclear who commanded them - Italian sources write that the Duke of Ferrara controlled all the artillery, French sources - that he could only command his gunners.

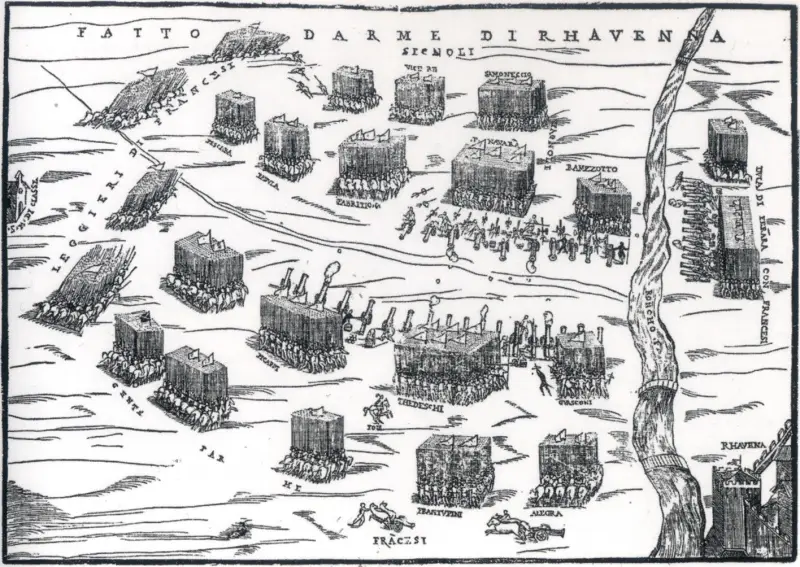

The Battle of Ravenna in an engraving. If desired, you can make out the inscriptions of Tedeschi (Germans), Francesi and Gascony

However, there was no immediate attack. Instead, the French artillery began shelling the Spanish battle formations, and the Spaniards responded in kind. The mutual shelling lasted more than two hours. This is sometimes called the world's first artillery duel, which is inaccurate since the duel involves shooting at each other.

The French quickly realized that their fire was ineffective. Then Alfonso d'Este, who was on the French left flank, moved his guns (or part of them) even further forward and to the left, so that it became possible to conduct flanking fire. On the right flank, the French sent two cannons across the bridge to the other side of the Ronco and also began shelling the Spanish, or rather Italian, cavalry. In other words, the French were the first in the world to use the artillery maneuver with wheels and organize a fire bag.

As a result, mutual shelling had an effect. The Spanish infantry could have taken cover in a ditch or simply lay low, but the Spanish and Italian cavalry had a more difficult time, and ultimately they emerged through the passes on both flanks and attacked the French cavalry (here and in what follows I greatly simplify the description of the battle in order to do not sort out all the contradictions in the sources). However, these attacks were repulsed with heavy losses, and the Spanish-Italian cavalry left the battlefield, and the French pursued it.

In the same way, the French infantry, being in open space, suffered heavy losses - up to 2 thousand [3], and could not remain in place - it had to either go forward or run back. Of course, this means all the infantry - Picardians, Gascons, Landsknechts and Italians. Therefore, as soon as success was evident on the flanks, this entire international army launched an assault on the Spanish camp. Under the fire of Spanish cannons and then arquebuses, they crossed the ditch and began a battle with the Spanish infantry between carts, guns and other obstacles. This is where the rodeleros showed their best side. Gradually the attack fizzled out.

Then the Spanish infantry launched a counterattack. Similar timely counterattacks have already led to victory several times, but in this case the situation turned out to be different. The French and Gascons could not withstand the blow and fled (the Gascons also had their commander killed). The Landsknechts, despite the losses—Jacob Empser, his deputy and many lower-ranking commanders were killed—still held out. The cavalry came to their aid, returning from pursuit and hitting both flanks of the Spaniards. Then the infantrymen from the reserve arrived, and behind them the fleeing French and Gascons turned around.

Also an engraving depicting this battle.

Now the Spanish infantry found themselves in a difficult position, some of the colunels were surrounded and cut down, the rest fought their way to the south; The papal infantry fled. Those colunels who were pursuing the retreating suddenly discovered that they had to save themselves. The difference was that these units retained their combat effectiveness.

Cardona himself escaped even earlier, Don Pedro de Navarro and a number of other commanders - Pescara, Colonna, la Palud, Giovanni Medici were captured. The Spanish camp and artillery were captured by the French. Cardona, who later reached the borders of the Kingdom of Naples, was able to gather a little more than 3 thousand infantry who retained their combat capability.

And then something terrible happened, for the French, of course.

For the 16th century, it was the norm for generals to fight in the front ranks of their troops, and young Gaston de Foix was no exception. In the heat of battle, he, with only two dozen knights, attacked one of the retreating colonels, was knocked off his horse and killed before help arrived. A dozen wounds were found on his body.

According to Italian sources, in fulfillment of a vow to his lady, Gaston fought that day without a helmet or elbow pad. If this is so, then all that remains is to throw up your hands - after all, he is a smart person.

A look from the other side. Gaston is clearly not 22 years old here.

The battle of Ravenna was incredibly fierce. Even the victors had very serious losses - from 3 thousand [16] to 4,5 thousand killed [1] and even more wounded. Many commanders were killed, the Landsknechts suffered especially heavy losses - out of 15 commanders, 12 were killed or wounded. The losses of their opponents were twice as high; in fact, their army ceased to exist.

However, the death of Gaston de Foix turned a complete victory into a pyrrhic one in a few seconds. The difference is that Pyrrhus found himself a commander without an army, and after Ravenna the French army was left without a commander. Chosen by the surviving military leaders, La Palis was a valiant knight and a good detachment commander, but as a commander he had neither energy, authority, nor even formal authority from the king.

The mood of the army was expressed by Bayar in a letter to a relative - the king may have won the battle, but we, the poor nobles, lost it. However, the king himself was of the same opinion, as a contemporary wrote, having learned the circumstances of the victory, the king began to cry and exclaimed: “It would be better if I lost all the states that I own in Italy, if only my nephew and so many brave captains remained alive! May heaven, in its wrath, reserve such victories for my enemies!”

Death of Gaston de Foix

The events that followed justified all fears. As if by inertia, the army captured Ravenna (and, of course, thoroughly plundered it), but then La Palis, instead of immediately marching on Rome, lost precious time by returning with the army to Milan to receive guidelines from King Louis XII. But, apparently, Louis XII was too upset by the death of his nephew, so the instructions were also not the wisest - to send half of the army to France, with the other half, or rather, with the part that still remained after the departure of the Landsknechts, to lock themselves in the fortresses. As a natural result, not even a year had passed before all of northern Italy was lost to the French.

The king commissioned the Milanese sculptor Agostino Busti, known as Bambaya, for a luxurious tomb, which, unfortunately, has not been completely preserved. But the tombstone itself is now kept in Milan in the Castello Sforzesco, i.e. in the Sforzesco Castle. This castle is worth visiting just for this reason.

The eternal dream of Gaston de Foix

Sources:

1. Battle of Ravenna, 11 April 1512.

2. Gaston de Foix, Duke of Nemours, 1489–1512.

3. Death of the Fox: Battle of Ravenna (1512) By William E. Welsh.

4. Gaston de Foix-Nemours.

5. Italian wars. Military encyclopedia (Sytin, 1911–1915).

6. European firearms artillery of the 14th–16th centuries. [Yuri Tarasevich]

7. From Agnadello to Ravenna: the Italian route of Gaston de Foix. Author: Alazar Florence. Translation: S. A. Burchevsky.

8. Jacques II de Chabanne, lord of La Palis.

9. Il sacco di Brescia di cinquecento anni fa.

10. Soffrey Alleman, dit le Capitaine Molard, seigneur du Molard* et baron d'Uriage, lieutenant général du Dauphiné, capitaine général des gens de pied de l'armée du Roi en Italie … cousin du chevalier Bayard…

11. Soffrey Alleman.

12. The life and times of Francis the first, king of France [by J. Bacon]

13. Julian Klaczko, Rome and the Renaissance. The game of this world 1509–1512.

14. Carlo Pasero Francia Spagna impero a Brescia 1509–1516.

15. Military revolution of the 16th–17th centuries: tactics. The original was taken from Aantoin. Military revolution of the 16th–17th centuries: tactics.

16. Battle of Ravenna 1512.

17. Battle of Ravenna (1512).

18. La Battaglia di Ravenna del 1512.

Information