Alexander Menshikov. The beginning of a long journey

Alexander Danilovich Menshikov is one of the most grandiose figures of Peter the Great’s time, rich in strong personalities. In front of his shocked contemporaries, a young man who came from nowhere and was not at all noble suddenly became the second man in the Russian Empire. It was his signature that was the first on the death sentence for the heir to the throne - Tsarevich Alexei, the son of Peter I.

He was also the only duke in the Russian Empire (Izhora, from 1707), the first cavalry general in Russia (now they would say “marshal of the military branch”) and the first Russian member of a foreign academy of sciences (Isaac Newton sent him notice of his election).

By the way, Peter I himself became a member of the foreign academy of sciences (French) three years later than Menshikov. Here is the complete “Form” that the hero of our article used in official documents:

"Pie" or nobleman?

The origins of Menshikov are still debated.

Many are sure that he came from the common people and as a child sold pies and pancakes in Moscow. This version became very popular after the publication of A. Tolstoy’s novel “Peter I”.

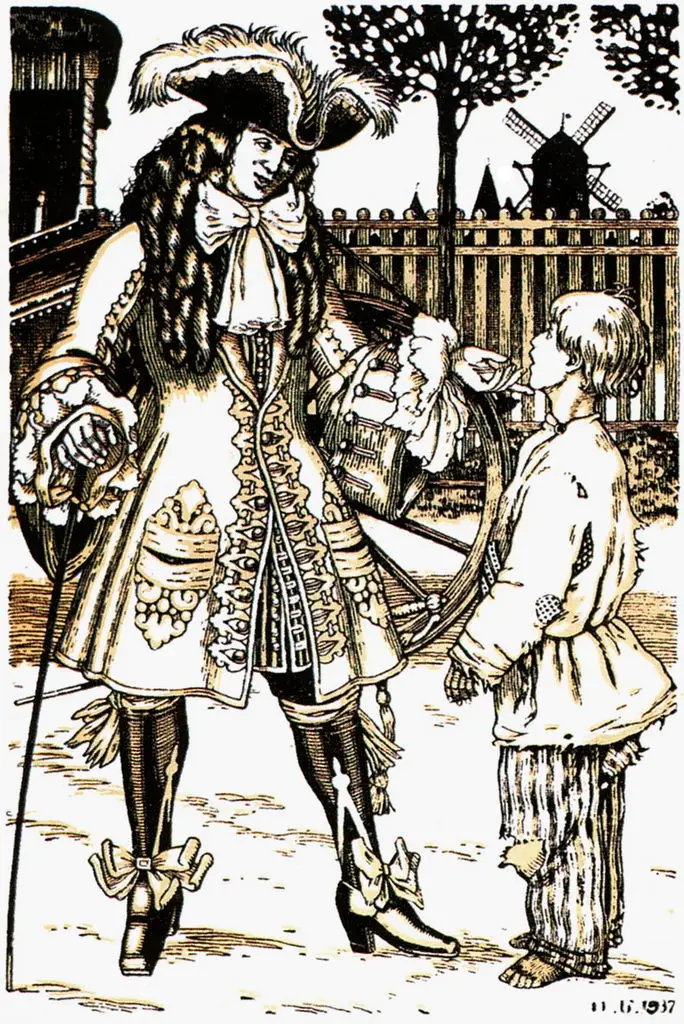

Menshikov with pies, illustration for A. Tolstoy’s novel Peter I

And Pushkin in this line in the poem “My Genealogy” speaks specifically about the hero of the article:

In the poem “Poltava” Pushkin gave everyone the well-known coined formula:

However, in the preparatory materials for the unfinished work "History Peter" he also notes:

Pushkin suggested looking for the family estate of the Menshikov family near Orsha.

But Prince Kurakin, who also wrote the history of the reign of Peter I (and also did not finish it) believed that Menshikov was “of the lowest breed, below the nobility.”

The royal “diplomas” say that Menshikov:

Let's see what his contemporaries wrote about the origin of Menshikov, arranging this evidence in chronological order. Here is the very first: in 1698, the secretary of the Austrian embassy, Korb, in his “Diary of a Travel to Muscovy” calls the hero of the article “the tsar’s favorite Aleksashka.” He reports:

In 1704, Martin Neugebauer, the tutor of Tsarevich Alexei, who fled abroad, published a brochure in which he claimed that Menshikov was a “pie maker” and a “peasant son.”

A German in Russian service, Heinrich von Huyssen, on the contrary, wrote in 1705:

But in the same year, the English Ambassador Whitworth reported to London that Menshikov

In December 1707 in Novogrudok, at the congress of the gentry of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a letter was sent to Alexander Danilovich, already his Serene Highness, where he was addressed as “Alexander Menzhik, our master and brother, a commoner of our kind” and recognized him as “our fatherland of the principality Lithuanian son."

However, in this document there is no mention of either the noble coat of arms of Menshikov or his family estate. And we must take into account that Menshikov was already his Serene Highness and a prominent military leader. He and his troops are in Belarus, and no one can stop him from ordering some regiment to visit the estate of a slow-witted deputy and see if there is anything interesting there, and whether this “interesting” would be suitable for the needs of the Russian army. Then complain anywhere, to anyone, and as much as you want.

Later, Menshikov, indeed, acquired estates in Belarus, but they were presented to him by Peter I. And Alexander Danilovich never had Belarusian relatives.

In 1710, the Danish ambassador Joost Jul writes in his diary:

The Tsar's turner Andrei Nartov reports that one day, angry with Menshikov, Peter began to threaten him to “turn him back to his previous state at once.” Menshikov ran out into the street, took the body from some pie maker and, hanging it on himself, returned to the palace, making the Tsar laugh and thereby achieving forgiveness.

A Frenchman in the Russian service, Vilboa, adjutant of Peter I, then vice admiral, claimed that Menshikov’s father

Burchard Minich considered Menshikov’s origins “from commoners” to be an indisputable and well-known fact. His adjutant Manstein also writes:

After the death of the first emperor, in July 1727, a certain artisan of the city chancellery, Daniil Kolosov, brought the authorities an anonymous letter directed against Menshikov, in which the anonymous author wrote that the temporary worker

That is, Menshikov’s father is called a sutler – a seller of food for soldiers.

What about the Menshikov estate near Orsha?

It probably never existed. And there is reason to believe that, despite the document from the delegates of the gentry congress of 1707, in fact no one had heard of the Menshikov nobles in Belarus. For example, Yuri Trubnitsky, one of the members of the Mogilev magistrate, having received the news of Menshikov’s death, wrote that Peter’s favorite

That is, the circle is closed, and we again find ourselves in Moscow, where young Aleksashka Menshikov sells either pies or pancakes.

Parents of Alexander Menshikov

The earliest document containing information about A. Menshikov’s father is dated October 13, 1689: in the “Notebook of the Streletsky Order” you can find an entry about

Born on November 6 (16), 1673, Alexander was 16 years old at that time. It is known that Menshikov’s father later served in the Semenovsky regiment and died during the first siege of Azov.

The hero's mother, Anna Ignatievna, came from a merchant family. In 1695, Menshikov even inherited from one of his relatives shops in the Zhelezny and Syreiny rows. That is, the hero of the article cannot be called completely poor.

To summarize, we can say that Menshikov was a very dubious nobleman, and the possibility of assigning him this title cannot be ruled out. Peter I, of course, did not interfere with this, since it was somehow inconvenient for the tsar to bring a person of peasant origin closer to him.

The early life of Alexander Menshikov

So, the first documentary evidence about A.D. Menshikov dates back to the late 1690s, and from that time the “semi-legendary” period of his life ends, and the well-known “historical” period begins.

According to the most common version, young Peter first saw Menshikov in Lefort’s house, where he was in service. A tall and cheerful teenager, almost the same age as the Tsar (a year younger than him), apparently by that time he had already “cut his teeth” in the German Settlement, knew some foreign words, and learned some “polites.”

But François Guillaume Villebois, mentioned above, also gives a version of Menshikov’s acquaintance with Peter:

By the way, this is exactly how Mark Twain’s novel “The Prince and the Pauper” begins.

Soon Peter and Alexander became friends and, as they say, sometimes even slept in the same bed (“hussars, keep quiet”!).

Ivan Golikov, the author of a 30-volume work about Peter I written in the XNUMXth century, tried to combine all versions:

Then, according to Golikov, in 1686 he became a servant in Lefort’s house, and from him went to Peter.

Lefort and Menshikov, illustration by I. Bilibin for A. Tolstoy’s novel “Peter I”

And here is the opinion of S. M. Solovyov:

Appearance of Alexander Menshikov

Dmitry Bantysh-Kamensky in “Biography of Russian Generalissimos and Field Marshals” (1840) gives the following description of the appearance of the hero of the article:

His Serene Highness Prince A. D. Menshikov in a portrait by an unknown artist

And here is what S. M. Solovyov writes about Menshikov:

Beginning of the royal service

Since 1693, Menshikov served in the bombardment company of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, whose captain was Peter, in 1699 he became its sergeant, in 1700 - lieutenant. He took part in the Azov campaigns of 1695–1696, then Peter I included him in the Great Embassy of 1697–1698.

M. van Musscher. Portrait of A. Menshikov, painted in Holland during the Great Embassy (1698).

Together with the tsar he worked in shipyards, studied artillery, and learned German and Dutch. In addition, he was in charge of the economic affairs of the Embassy. Upon returning to Russia, he became one of the tsar’s most active assistants, taking an active part both in the “Assemblies” and in the very dubious and obscene entertainment events of this tsar.

North War

One of the results of the Great Embassy was the creation of an anti-Swedish alliance between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (the Polish king Augustus III was also the Elector of Saxony). The Kingdom of Denmark and Norway also joined this union.

Russia's goal in the coming war was to regain control of the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea, which had fallen under Swedish rule during the Livonian War. In 1583, Russia was forced to conclude the Truce of Plus, according to which it lost, in addition to Narva, three border fortresses (Ivangorod, Koporye, Yam), retaining only Oreshek and a narrow “corridor” along the Neva to its mouth, a little more than 30 km long.

In 1590, the government of Boris Godunov (under the nominal Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich) attempted to regain the lost territories. The war ended in 1595 with the signing of the Tyavzin Peace, according to which Russia regained Yam, Ivangorod and Koporye.

Russo-Swedish War 1610–1617 ended with the signing of the Stolbovo Peace Treaty, under the terms of which the Swedes returned Novgorod, Porkhov, Staraya Russa, Ladoga, Gdov and Sumerskaya volost to Russia, but received Ivangorod, Yam, Koporye, Oreshek and Korela. Under Alexei Mikhailovich, Russia tried to recapture these lands, but was unsuccessful.

The Kingdom of Sweden at the beginning of the 18th century was a large European country. In addition to Sweden itself, this state also included Finland, Livonia, Karelia, Ingria, the cities of Wismar, Vyborg, the islands of Rügen and Ezel, part of Pomerania, the duchies of Bremen and Verden.

Kingdom of Sweden on the map

The military reputation of the Swedes, starting from the Thirty Years' War, was very great, the army was famous for its discipline and high fighting spirit. Swedish historian Peter Englund in his work “Poltava. The Story of the Death of an Army" gives the following assessment of the army at the disposal of Charles XII:

But on April 14, 1697, a new king, Charles XII, ascended to the Swedish throne. At this time he was 14 years 10 months old, he had a well-deserved reputation as a good-for-nothing scoundrel, and therefore no one expected any feats from him. However, the Northern War awakened in this young man not even a Viking, but a berserker; his contemporaries compared him to Alexander the Great. The Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation, Joseph I, in 1707, in response to the reproaches of the papal nuncio for concessions to the Protestants of Silesia, said:

The first battle of the Russian army in the Northern War was the unfortunate Battle of Narva, which took place on November 19 (30), 1700. Menshikov did not take part in this battle, since Peter I, who left for Novgorod, took him with him.

This victory for Charles XII turned out to be truly fatal, since as a result he made an absolutely logical, but completely wrong conclusion about the weakness of Russia and the need to focus his attention on more worthy and powerful opponents in Europe. But Russia was not defeated and received its most valuable resource at that time - time.

Already 2 weeks after the Battle of Narva, Sheremetev at Marienburg dared to attack (albeit not very successfully) the Swedish detachment of General Schlippenbach. A year later (December 29, 1701), at Erestfer, Sheremetev’s troops inflicted the first defeat on Schlippenbach’s corps, for which the Russian commander received the rank of Field Marshal and the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called. Schlippenbach was then defeated twice in 1702.

In the fall of 1702, Menshikov distinguished himself during the assault on the Noteburg (Oreshek) fortress: he ordered the collection of boats and used them to deliver reinforcements to the walls of the fortress. The Russian troops were then led by Peter himself.

A.E. Kotzebue. "Storm of the Noteburg fortress on October 11, 1702"

This fortress was renamed Shlisselburg, and the hero of the article became its commandant.

In the spring of 1703, Russian troops occupied Izhora land. Menshikov participated in the capture of Nyenskans, which was renamed Schlottburg. The Swedes, who did not know about the fall of this fortress, placed two ships near it - the 10-gun bot "Gedan" ("Pike") and the 8-gun shnyava "Astrild" ("Star"). On May 7 (18), Peter and Menshikov on boats led an attack on these ships, “Gedan” was captured by the team of Menshikov, who, at the same time as Peter I, then received the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called.

L. Blinov. Capture of the boat "Gedan" and the shnyava "Astrild" at the mouth of the Neva. Central Naval Museum

Already on May 16, the first bastion of the Peter and Paul Fortress was founded on Hare Island, Menshikov became the first governor of St. Petersburg, supervised the construction of this city and Kronstadt, founded shipyards on the Neva and the Svir River, and two cannon factories.

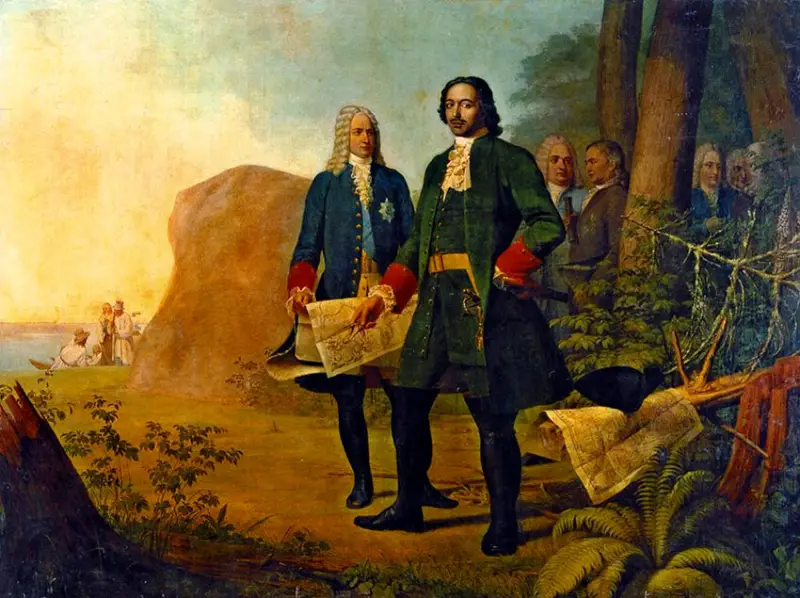

Menshikov and Peter I at the foundation of St. Petersburg

In July, by order of the tsar, he formed a new regiment, later called Ingria.

In May 1704, near the besieged Narva, at the suggestion of Menshikov, they managed to provoke the Swedes into a sortie. Soldiers from 4 regiments, dressed in blue uniforms similar to Swedish ones, approached the fortress. Part of the troops of the Swedish garrison came to the aid of their compatriots, losing up to 300 people. However, it was possible to take Narva by storm only in August.

On November 30, 1705, Menshikov became a cavalry general. In the same year, he was awarded the Polish Order of the White Eagle and received the title of Prince of the Holy Roman Empire (he became a count back in 1702).

Jan Hendrik Beering. Portrait of A. Menshikov, 1705

On October 18, 1706, Menshikov played a big role in the victory of the allied army near Kalisz: he personally led the decisive attack of the Russian dragoons and was wounded. The surrounded Swedes surrendered - along with the commander-in-chief Arvid Mardefelt.

Peter Pickart. Prince A.D. Menshikov against the backdrop of the Battle of Kalisz. 1707–1708

The battle of Kalisz is called the first “proper battle”, in which the Russian army won. The next day, Kalisz also capitulated. As a reward, Menshikov received the rank of lieutenant colonel of the Preobrazhensky regiment. In August of the same 1706, the hero of the article married Daria Mikhailovna Arsenyeva, who was the daughter of a Yakut governor. It is curious that this woman signed her letters to her husband “Daria Stupid.”

Daria Mikhailovna Menshikova in a portrait by an unknown artist

This marriage produced 7 children, but four of them died at an early age. The fate of the rest will be discussed later.

In 1707, Menshikov fought in Poland. But the main battles were ahead. We will talk about this and much more in the next article.

Information