“And the last became first”: how Moscow first tried to subjugate Kazan

Capture of Vasily II in the battle of Suzdal. Miniature from the Facial Vault

In the mass consciousness, the year 1467 on the Russian-Kazan timeline remained without a red flag: no one was conquered, no high-profile battles, assaults or sieges happened. However, this is an important turning point when it finally became clear: “the last became the first.” Moscow, formally still a Tatar tributary, dared to try to establish its assistant in Kazan, taking advantage of the instability within the Volga Khanate. And although the experiment ended with the fact that the Moscow troops and allied Kasimov Tatars “I'm tired of the way back", the first step towards the establishment of a Russian protectorate was taken.

From tributaries to overlords: why Moscow expanded into Kazan

According to the fair remark of researcher Alexander Bakhtin, in the feudal era, a precarious peace between neighboring states could be maintained only if they had approximate military and economic parity. As soon as one of the “partners” rose above the other, the strongest immediately began expansion. He either decided on a full-fledged conquest, or sought to at least establish his own protectorate over adjacent territories. This provided benefits such as tribute collection, duty-free trade, and an additional security buffer on the borders.

The rivers did not flow back in the case of Moscow and Kazan. While the first has not yet become stronger and has not gathered around itself most of the Russian lands, the Kazan people confidently “lead the score.” The troops of the founder of the Kazan dynasty, Ulu-Muhammad, crush the Russian regiments near Belev, his sons defeat and capture Grand Duke Vasily II near Suzdal in July 1445. Then they completely impose a shameful and enslaving tribute on Moscow and imprison their Baskaks in Russian lands. It would seem that Batu’s times have returned - and the end of the world is just around the corner.

But no! Before the long-suffering Vasily II the Dark had time to give his soul to God, a turning point emerged in the relationship between the two states. In 1461, the Grand Duke, who had only a year to live, gathered an army and set out on a campaign against the Kazan Khanate. Khan Mahmud turned out to be unprepared for war, and diplomats had to take the rap. An embassy moved from the banks of the Kazanka to the Grand Duchy of Moscow (VKM), which met Vasily II near Murom. As a result, war was avoided.

Since then, the Kazan khans had to abandon their “Batyev” ways and “get their teeth into” at least parity with Moscow. But it didn’t last long either. Since the late 60s of the XNUMXth century, Grand Duke Ivan III became so bold that he set his sights on establishing his influence over the Khanate.

This course was explained not only by the sharp strengthening of the ECM and the harsh “law of the jungle”. Firstly, the Kazan people themselves, although they were losing their leading positions, still posed a threat, at a minimum, to the Russian border lands. Secondly, control over the Volga Khanate was the key to fulfilling a number of economic, political and strategic tasks vital for the Moscow state. Let us briefly outline the main ones.

The fight against Kazan raids for the purpose of capture is complete. The volume of Kazan trade in Russian prisoners is a controversial issue in historiography. “The main article of the Kazan economy,” as some claim, it was not. Nevertheless, Nizhny Novgorod, Kostroma, Ryazan, Murom, Ustyug and other lands were regularly subjected to raids in order to seize booty and food, and back in the 40s of the XNUMXth century, the Kazan people besieged Moscow no less. Over time, the offensive initiative was firmly entrenched in the Russian state, but right up to the conquest of the Khanate under Ivan the Terrible, the invasions of the Volga Tatars, as well as counter “courtesy visits,” did not stop. The Russian-Kazan borderland remained a real frontier, about which it was time to make late medieval “austerns”.

It is not without reason that the most important point of the first peace treaty between the two states in 1469 reflected in the sources will be the return of “Russian captivity for four ten years" But in general, the strategically unsuccessful campaign against the Kazan territories under the leadership of Ivan Runo in the same year will appear in the chronicles almost as a triumph. After all "that the village was full of Christians: Pskov, Ryazan, Lithuanian, Vyatka, Ustyug and Perm, and other other cities, they were all full" [1]. And the “Polonian money” tax, designed to compensate for population loss due to Tatar raids, was not invented just like that.

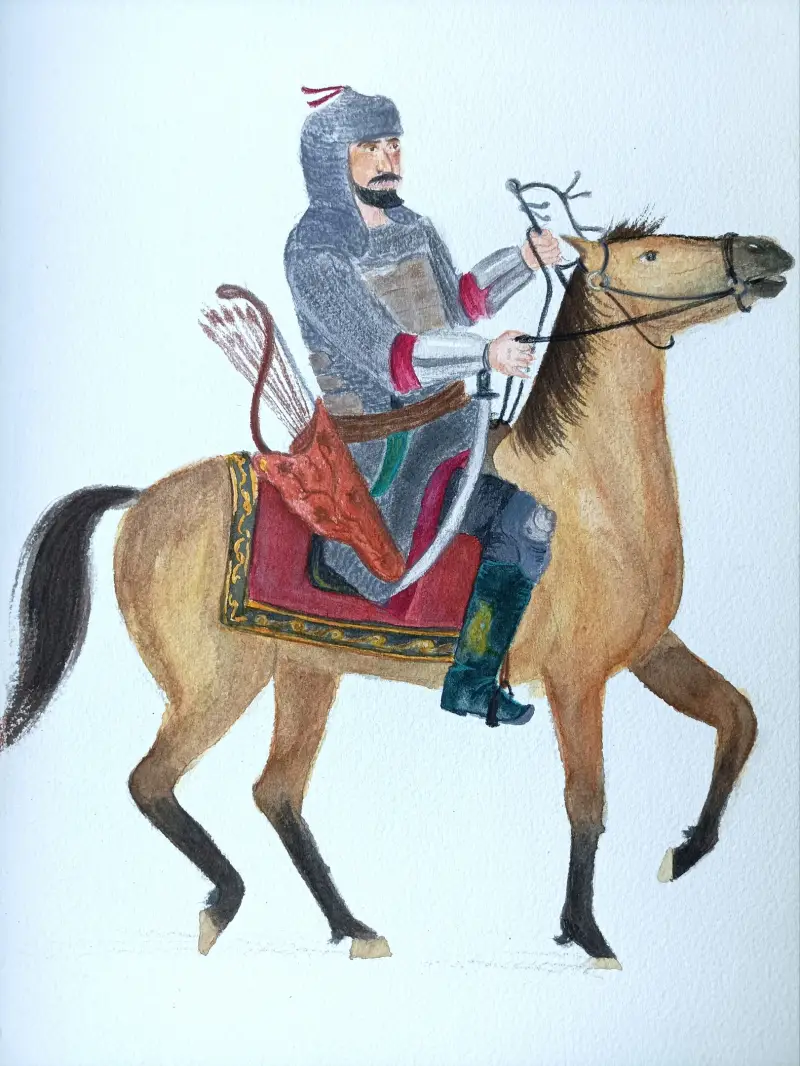

Kazan Murza of the 16th century. Rice. N. Kanaeva

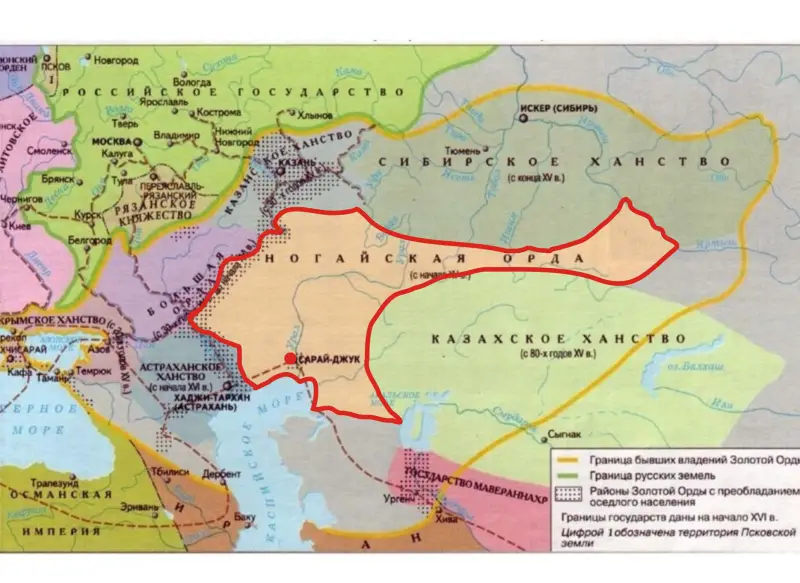

Regulation of Kazan-Nogai relations. Such a task was extremely important in the context of the same trade in Russian meat. Until a certain point, it was mainly the Nogais who spurred the Kazan people to raid Moscow territories. In exchange for the Russian “polonyanniks”, cattle, leather, and horses came to Kazan from the Nogai Horde (also known as the Mangyt yurt).

The Nogais stimulated the Kazan residents to attack Moscow not only economically. In the second half of the 1487th century, the former were widely represented at the court of the Kazan ruler; the elites of the two states had close matrimonial ties. It was the Nogais who played the first violin in the eastern (anti-Russian) aristocratic “party” of the Volga Khanate. This Kazan-Nogai Gordian knot needed to be cut or at least weakened, which Ivan III would subsequently do already in XNUMX. The Khan's coordination of all relations with the Mangyt Yurt will become an important point of the first Russian protectorate over Kazan.

Improving the land situation. The “cast iron back” of the feudal economy was agricultural land, which was absolutely in short supply for everyone. The land problem was especially acute in areas of risky agriculture such as VKM. And here Kazan is nearby with its “milk rivers and jelly banks”, glorified in colors already under Ivan the Terrible by publicists. It was also necessary to take estates from somewhere for the multiplying service people, who were gradually turning into the main striking force of the sovereign.

In the 60s of the XNUMXth century, there was no talk of any annexation and development of the Kazan lands directly, as well as of the placement of Moscow boyar children there - the Russian state could not yet chew such a piece. But the persistent protectorate over the Volga Khanate also had a beneficial effect on the land issue, since the Russian-Kazan borderland was freed from constant military danger. The same boyar children could calmly settle, say, to the left of the Sura and not expect that at any moment they would have to meet guests from the right bank and defend their plots.

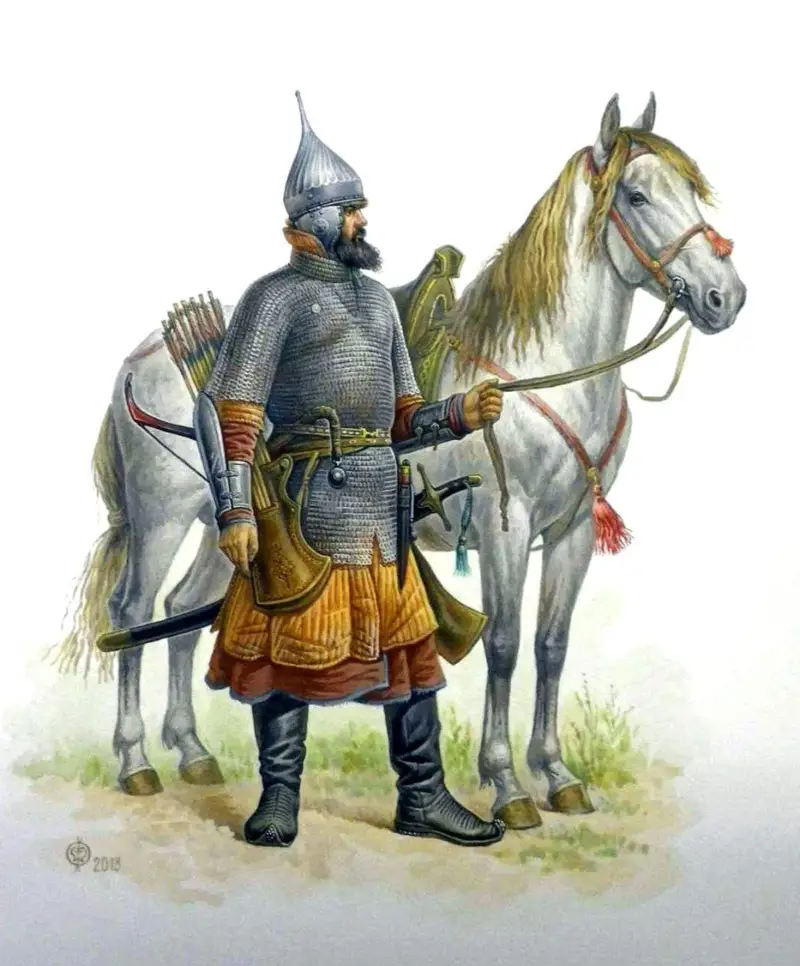

Moscow boyar son of the 15th–16th centuries

Preventing the rapprochement of Kazan with the Great Horde. At first glance, Sarai was as hated by Kazan as by Moscow. This enmity arose even before the formation of the Volga Khanate. At one time, representatives of the Chingizid branch, which had established itself in the Great Horde, removed the future founder of the Kazan dynasty, Ulu-Muhammad, from the Sarai throne.

However, in the face of a common external threat, yesterday's sworn enemies are uniting. Kazan’s attitude towards the Great Horde was indeed not distinguished by friendliness, but officially neutrality was maintained between them. The Volga Khanate did not fight either with or against Sarai. Unlike the Crimeans, the much more sedentary Kazan residents did not have any views of the Greater Horde nomads. If you think about it, dynastic enmity was not such a serious stopping factor for the cooperation of these two Tatar yurts against Moscow.

Control of the Volga trade and access to the Caspian Sea. After the emergence of the Kazan Khanate, trade between Moscow and the Volga cities, as well as a number of eastern states, especially intensified. On Gostiny Island, not far from Kazan, an international fair opened every spring, where merchants from the Crimea, the Caucasus, Turkey, the Nogai Horde, Astrakhan, Central Asia, and Rus' gathered. It was a real center of the world, where colossal funds were circulated, goods were exchanged and the news people from different parts of the world. Controlling such a “Tatar Caput Mundi” turned out to be extremely beneficial for Moscow from both a commercial and strategic point of view.

Fair on Gostiny Island near Kazan. Painting by F. Khalikov

It gave Muscovites the subordination of Kazan and almost unhindered access to the Caspian Sea, which meant direct duty-free trade with the Caucasus, Persia, Shirvan, Khiva, Bukhara and other countries of the East. Of course, from Moscow to the countries of the Thousand and One Nights and back they sailed along the Volga-Caspian route even before the establishment of a Russian protectorate over the Kazan Khanate. But even at the beginning of the 16th century, this practice was irregular. For a long time, Kazan remained a huge Volga gateway, the gates of which were either opened or closed for Russian merchant ships, depending on the military-political situation. And transit duties could absorb all the benefits of a risky and distant journey “far away.” The Volga Tatars were well aware of the powerful lever of economic influence on their western neighbor that was in their hands, and they used it at every convenient opportunity.

It would not hurt the Russian state to streamline the trade in Nogai horse stock directly in Kazan and through it. It was the massive transition from expensive “knightly” horses from Persia and Asia Minor to relatively cheap and small Tatar horses that allowed Moscow to create a large orientalized army. And by “Tatar” we should first of all understand Nogai. A huge share of horses and cattle involved in Russian agriculture were also purchased from people from the Mangyt yurt.

Taking advantage of this, they made the most of trade with Moscow, in which their Kazan partners helped them. Firstly, more than 20 horses were sold annually at the equestrian area in the suburb of the capital of the Volga Khanate, not far from the Tezitsky courtyard. Secondly, the Nogais drove huge herds (up to 000 thousand heads) to the Grand Duchy of Moscow for sale along with embassies. Interesting information about the arrival of the Nogai diplomatic mission in 40, which also included horse traders, is contained in a book on relations with the Nogai Horde:

Since such an order - not to provide horse feed for sale - was separately prescribed by the Grand Duke, such demands from the Nogais were not uncommon. Often their business plan was completely expanded by the plunder of territories along the embassy route: the Russian sovereign even had to send escorts of boyar children to meet the guests. In a word, it was necessary to somehow bring the Nogai “suppliers” to their senses, and control of such an important sales point as Kazan helped to do this. Moreover, the aforementioned embassy-trade-robber avalanches passed duty-free, including through the Kazan territories on the way to Moscow.

Expanding diplomatic ties in the eastern direction and increasing the international prestige of Moscow. Along with trade, the diplomatic relations of the Russian state in the East also depended on Mother Volga, since ambassadors used exactly the same routes as merchants. For example, in 1465, an embassy from Shirvanshah Ferrukh-Esar reached the Grand Duchy of Moscow for the first time along the Volga route. Already in 1466, a diplomatic mission headed by Vasily Panin went on a return visit to Shirvan, and at the same time the Tver merchant Afanasy Nikitin, who began his famous “Walk across the Three Seas”. It was necessary to secure this most important artery as much as possible for diplomats, whose ships were continually attacked by Kazan, Nogai, and Cossacks.

Finally, the protectorate over one of the most developed fragments of the Golden Horde increased the status of the Russian state, which was growing stronger by leaps and bounds, in the international arena. Yesterday's tributary himself conquered one of the Tatar kings, therefore, in the eyes of the world community, he is a strong player who is better to be reckoned with.

And so, the Kazan people themselves suggested to Ivan III a way to achieve all the designated goals. Let's take a closer look at how this happened.

Background to the Volga campaign of 1467: “total mistake” of the Kazan succession to the throne

Ivan III barely had time to sit on the throne of his late father when, in the first year of his reign, he organized a campaign against the Kazan Khanate. More precisely, to the lands of the Cheremis, who continued to disturb the Moscow border territories. Russian troops reached all the way to Great Perm, which was under partial Kazan control.

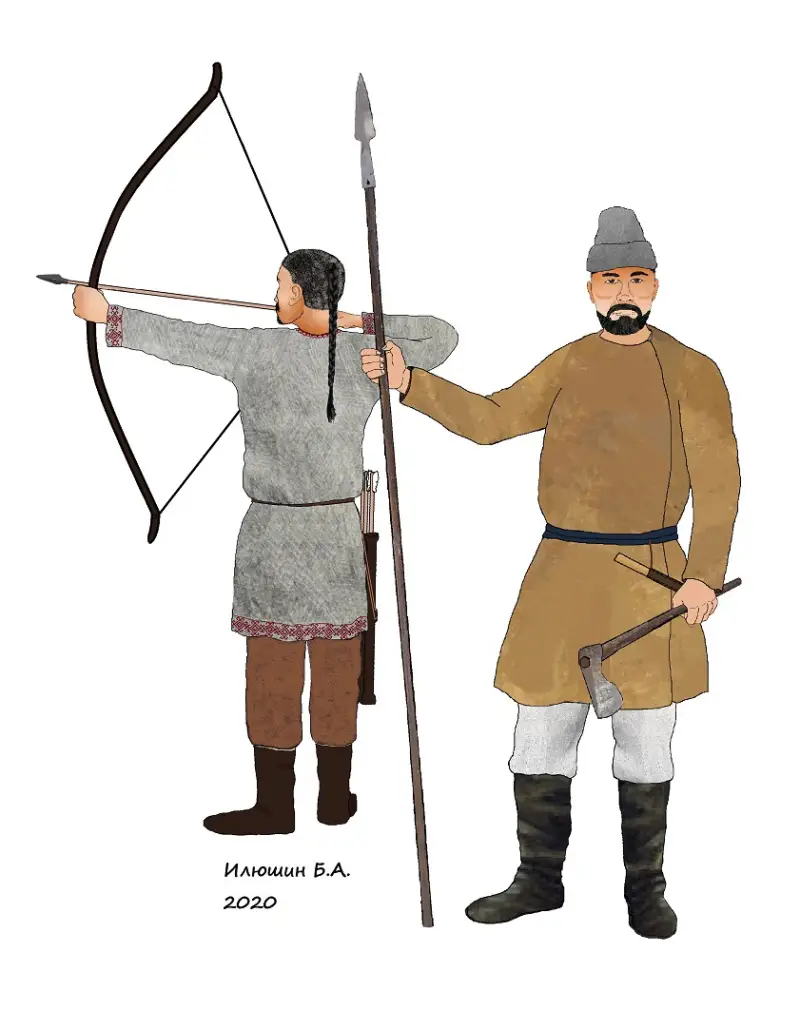

Cheremis warrior of the 15th–16th centuries. Rice. B. Ilyushina

There is little information about this operation in the sources. It is unknown how many troops went on the campaign and what results were achieved. Except for the response of the Kazan residents, who in the same year visited the Ustyug district together with the Cheremis. There, in the upper reaches of the Yuga River, they captured a large capt. However, the Ustyug residents were not at a loss and managed to catch up with the attackers and “full back full».

All these were the harsh everyday life of Russian-Kazan relations of that time, which cannot be said about the events of 1467. According to Konstantin Bazilevich and a number of other researchers, it was then that the pearl happened, when the Grand Duke loudly declared with his actions: we are going to the East! The window of opportunity was opened by the death of the valiant Kazan Khan Mahmud, who left behind two sons. One of them, Khalil, due to strange circumstances, died almost simultaneously with the priest. The second, Ibrahim, became the new Kazan king. Mahmud's widow, according to the good Tatar tradition, married the brother of her late husband. It was a certain Kasim, the head of the Kasimov Khanate located on the Oka and vassal to Moscow.

Such a combination greatly overloaded the Kazan succession machine, which produced a total error, to put it in the language of IT specialists. Ibrahim's uncle (Qasim) married his mother and also became a legitimate contender for the throne as the senior representative of the dynasty.

Among the Kazan aristocrats there were immediately forces who decided to turn the situation in their favor. A group of “princes” led by a certain Abdul Muemin sent messengers to Kasim with an invitation to the Kazan throne. Without leaving any intrigue, the chronicler immediately reveals his cards, they say, they invited the Moscow vassal by “flattery,” that is, by deception. Kasim, "trusting in them, but not knowing their flattery, ask the Grand Duke for strength, hoping to receive what was promised to him».

Kazan Campaign of 1467 or How Khan Kasim “failed face control”

Ivan III simply could not help but be pleased with the “business offer” of the Tatar princes or, more precisely, the beks. In their person, it was as if fate itself suggested a solution to the Kazan issue: to place their “son” on the khan’s throne and establish a protectorate. Without thinking twice, the Moscow ruler gathered an army under the leadership of Prince Ivan Vasilyevich Obolensky Striga, as well as the Tver commander Danila Dmitrievich Kholmsky, who had recently transferred to Moscow service. Together with Kasim, they moved to Kazan on September 14, 1467.

How many children of the boyar and Kasimov Tatars were with them, again, is unknown. But the authority and combat experience of the chief governor indirectly indicate a fairly representative contingent. Back in the 40s, Obolensky Striga distinguished himself in the fight against Dmitry Shemyaka on the side of Vasily II. In 1456, he inflicted a crushing defeat on the Novgorodians near Staraya Russa, thanks to which it was possible to conclude the Yazhelbitsky Peace Treaty, which was beneficial for Moscow. Striga also had a good administrative background, for example, he held the post of governor in Pskov and Yaroslavl. In a word, they would not bother such a distinguished person in order to lead a handful of people.

As the typographical chronicle reports, in addition to the cavalry army, the ship's army went on a campaign. The source also talks about the participation of the regiments of the Grand Duke's brothers. Meanwhile, according to the chronicle, he himself was in Vladimir with reserve forces. Although other sources do not say this, the report seems plausible. Even during the time of Vasily the Dark, Vladimir became a springboard for the fight against Kazan. Located 200 versts from Moscow, it was a convenient starting point for campaigns against the Khanate. From here it was possible to go down the Klyazma to the Oka, then exit to the Volga or continue the journey overland. In the event of a retaliatory invasion, the enemy would hardly have been able to significantly bypass Vladimir on the way to Belokamennaya. So the city of Monomakha served as a support base for both offense and defense. It was here that the Grand Duke's headquarters and mobilization platform unfolded, and at the same time the “field” military-administrative apparatus was concentrated.

Grand Duke Ivan III Vasilievich. Portrait image from the Tsar's titular book

While Ivan III was waiting in Vladimir, Kasim and his governors were met by the Tatars, although not in Kazan, as expected. If you believe the same Tiporafskaya chronicle, the rendezvous took place “to the mouth of Svityagi, to the Volga, opposite Kazan" It is curious that now they are talking exclusively about the cavalry unit of the Russian army. The declared ship's army disappears from the narrative without a trace, without firing, like a “broken Chekhov's gun.” But in theory it was supposed to be ahead of the cavalry. This makes Yu. G. Alekseev and other researchers doubt the reliability of other information from the source. For example, about the meeting place of Moscow troops with the Tatars.

The events in the Ustyug Chronicle are presented somewhat differently. It says that Russian-Kasimov troops met with the Kazan people in the area of the town of Zvenichev Bor on the Volga, 40 versts from Kazan. The Volga Tatars did not grab any carpets or welcome posters for Kasim, who had just been called to the Kazan throne. They arrived on ships, landed opposite the Muscovites and clearly intended to prevent the guests from crossing the river. Then the Russians came up with a daring plan: to lure the enemy to their shores and “drop the Tatars from the courts"to cross the Volga with them. The Kazan people allegedly almost took the bait, swam across the river and began landing. But what happened next proved once again that there is no place for the faint-hearted in war.

Here we can clearly see someone’s free statement, and not necessarily an eyewitness’s. The story about the unlucky bed guard, who rushed ahead of time to ambush the Tatars, looks like a fruit of folk art.

First of all, it is unclear how exactly the Tatars were lured out. Their task was to defend the crossing and prevent the enemy from crossing to their shore. The Kazanians occupied an advantageous position and could even push back the enemy with fewer numbers during the crossing of the river. And then the chroniclers would bitterly write down notes, they say, “there was a lot of Russian deluge in Volz.” It can be assumed that the Muscovites skillfully hid most of the army in an ambush. The Tatars, seeing a small number of the enemy, decided to cross the Volga and defeat them. However, this version seems very far-fetched.

One way or another, Kasim, who was invited to the “Kazan party” by “flattery,” did not pass the face control and, together with the governors, was forced to return home with nothing. This is what the Nikon Chronicle reports about their return journey:

This news was most likely recorded precisely from the words of an actual eyewitness to the events, since it contains a number of minor details. There was simply no need for the chronicler or anyone else to invent such a thing.

Returning to the chronicle account of Kasim’s false invitation to the khan’s throne, it is not entirely clear what kind of “flattery” (deception) is meant. It’s unlikely that the Kazan people planned to deal with Kasim or stage a prank in a feudal style: to call a pretender to the throne and ultimately not let him in. It seems that what we are really looking at is an attempt at a palace coup, which was discovered and countered in time by the khan’s government.

The conspirators could well have belonged to some kind of embryonic pro-Russian “party” of the Kazan aristocracy. In the Volga Khanate, everyone knew perfectly well that Kasim was a grand-ducal vassal, which means that his elevation to the throne entailed the establishment of a Moscow protectorate. Such a prospect was most likely accepted by part of the Kazan nobility, because Russian diplomacy was conducting serious recruiting work with them. Looking far ahead, by the 40s of the 1467th century, many of the Khan’s nobles would practically receive salaries from Belokamennaya in exchange for lobbying its interests. This practice has been tried since the time of Ivan Kalita in the Golden Horde, and after its collapse it was continued in Crimea, Kazan and other Tatar yurts. And yet, in XNUMX, the ground for establishing Russian influence in Kazan was still too shaky.

As we have already seen from the message of the Nikon Chronicle, Kasim and the Muscovites reached home without losses, not counting fallen horses, discarded armor and the taking of Orthodox soldiers in the “heavenly office” for eating meat (possibly those same fallen horses) on fast days. There were no sanctions against the governors from Ivan III. Apparently, in the opinion of the sovereign, Obolensky and Kholmsky did everything they could under the circumstances.

So, the adventure of 1467 failed, and very soon everything returned to normal. The Kazanians continued to invade the Russian border territories, the Muscovites continued to disturb the lands of the Cheremis. But over time, the offensive campaigns of the Russian troops became more and more daring: already in 1469 they twice reached the Khan’s capital. Moscow is turning into that same “great hunter", and Kazan - in "wolf", which is from him "got even“, as I. I. Lazhechnikov poetically noted in his historical novel “Basurmanin”.

List of references and sources

References:

Alekseev Yu.G. Sovereign of All Rus'. Novosibirsk, 1991.

Alekseev Yu.G. Campaigns of Russian troops under Ivan III. St. Petersburg, 2009.

Alishev S.Kh. Kazan and Moscow: interstate relations in the 1995th–XNUMXth centuries. Kazan, XNUMX.

Bazilevich K.V. Foreign policy of the Russian state: Second half of the 2001th century. M., XNUMX.

Borisov N.S. Ivan III. M, 2000.

Volkov V.A. Under the banner of Moscow. Wars and armies of Ivan III and Vasily III. M., 2016.

Ilyushin B.A. “War of the Summer 2014” Moscow-Kazan conflict 1505 – 1507. N. Novgorod. 2018

Ilyushin B.A. Kazan Wars of Vasily III. Kazan. 2021

History Tatars since ancient times. Volume IV. Tatar states XV – XVIII centuries. Kazan 2014

Penskoy, V.V. From bow to musket. Armed forces of the Russian state in the second half of the 2008th–XNUMXth centuries: problems of development. — Belgorod, XNUMX.

Sources:

Nikon Chronicle // Complete collection of Russian chronicles. T.13. M., 1965

Continuation of the Resurrection Chronicle // Complete collection of Russian chronicles. T.8. M., 2000

Ambassadorial book on relations between Russia and the Nogai Horde. 1489 – 1508

Ustyug chronicler // Complete collection of Russian chronicles. T.37. L., 1982

Typographical chronicle // Complete collection of Russian chronicles. T. 24.

Information