The fate of the condottiere. Bennigsen - a general who did not become a field marshal

Levin Theophilus von Bennigsen was born in 1745 in Banteln near Hanover and from a young age devoted himself to a military career. He took part in the Seven Years' War of 1756–1763, but at the age of 28, having reached only the rank of lieutenant colonel, he decided to offer his services to the Russian army. There, according to established tradition, which even affected Captain Bonaparte, Bennigsen faced a demotion in rank - to prime major in the Vyatka Musketeer Regiment.

Soon transferring to the Narva Regiment, Bennigsen fought with the Turks in the war of 1768–1774, under the command of Rumyantsev and Saltykov, but did not particularly distinguish himself. By the beginning of the next Russian-Turkish War, he was already a colonel and commander of the Izyum Light Horse Regiment, which would later become a hussar regiment.

The Hanoverian mercenary is already an experienced warrior, whom historians have not quite rightly called a condottiere, apparently due to the fact that Bennigsen did not accept Russian citizenship for a long time. However, not only Prince Potemkin, but also Suvorov himself drew attention to him. More important for his career was his acquaintance with Count Palen, and then with the Zubov brothers; besides, Bennigsen became a regular at the salon of Olga Zherebtsova, the Zubovs’ sister.

It is unlikely that it was Palen and the Zubovs who drew the Hanoverian, who, having become a general, managed to distinguish himself in Bessarabia, the Caucasus and in battles with the Polish Confederates, into a conspiracy against Emperor Paul. The five years of his reign were not easy for Bennigsen himself. At first he received the rank of lieutenant general, then fell into disgrace, and it is not surprising that he was among the participants in the coup, supported by the majority of the Russian officers. Grand Duke Constantine, not without reason, called Bennigsen “Captain of the 45,” since he was at the head of one of the two columns that penetrated the Mikhailovsky Castle.

Meanwhile, no one has ever refuted the phrase from the general’s mouth that Joseph de Maistre allegedly attributed to him: “The overthrow and imprisonment of him (Paul I) were necessary, but death is already disgusting.” Bennigsen is the only one of all the participants in the conspiracy who left notes about him, it is believed that he was trying to justify himself.

But “long Cassius,” by analogy with one of Caesar’s murderers, Gaius Longinus, he was called until his old age. However, Bennigsen is interesting to us not as a participant in the regicide, but as the conqueror of Napoleon. The rank of cavalry general and appointment as governor of Lithuania could mean the end of an active military career.

At this time, many were nominated who were younger than Bennigsen and inferior to him in seniority, and the heroes of Catherine’s era left one after another. Russia regularly fought on several fronts at once, and the need for experienced senior commanders was acute. Bennigsen returned to the army only in 1805, with the start of a new campaign against Napoleon.

Prussia at that time hesitated; even its action against Austria and Russia was not ruled out. Bennigsen was given command of one of the corps concentrated between Grodno and Brest for demonstration against the Prussians. It is believed that this prompted the general to finally accept Russian citizenship; he was even offered to convert to Orthodoxy.

The actions of Bennigsen's corps in that campaign were limited to advancing to Silesia to the fortress of Breslau, where a message about the Peace of Presburg had already arrived. But the next campaign - in Poland and old Prussia, which is now commonly called East, will become the most important in his career for the 60-year-old Bennigsen.

At Preussisch-Eylau, his army, as has already been said, if it did not win, then survived (The first winner of the invincible), but already near Friedland, due to an extremely unfortunate choice of position, Bennigsen could not avoid a heavy defeat. Friedland was called a defeat by Napoleon, but the Russians, even when put to flight, managed to escape to the other side of the Alle, retaining their strength.

The army, which received reinforcements from Russia, could still fight, but Emperor Alexander was already looking for peace. Quite recently, captured French banners were carried through the streets of St. Petersburg, and Bennigsen received the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called - there was no higher order in Russia. Now it was time for him to resign, although even the mistake that Bennigsen was accused of - an unsuccessful choice of position - was forced.

Before Friedland, Bennigsen almost defeated Ney’s corps and held out at Heilsberg, although even there the position was divided by the river bed. Bennigsen even had to organize the delivery of reinforcements across pontoon bridges, but he was unable to take advantage of the difficulties of Napoleon, who, having only one road on the left bank, brought his forces into battle in parts.

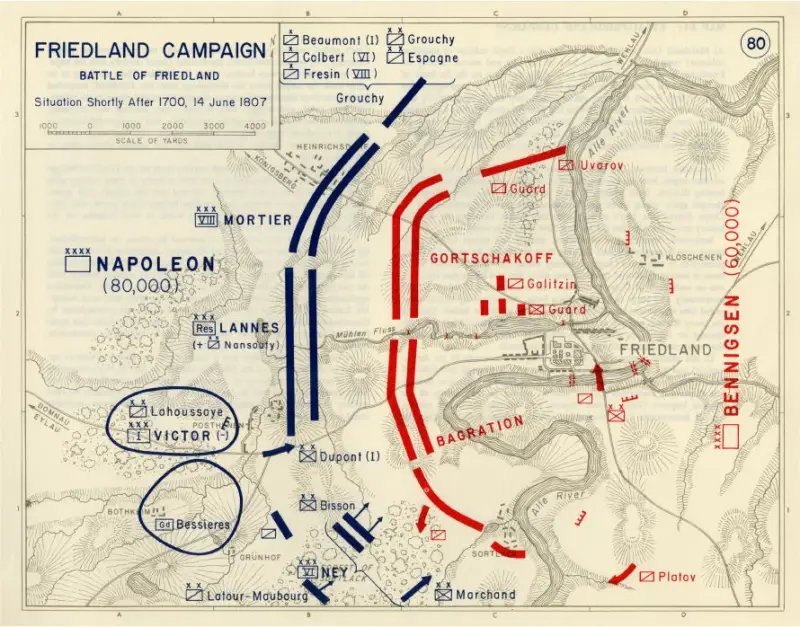

After retreating from positions at Heilsberg, due to the threat of an encirclement that could cut him off from Königsberg, the Russian commander-in-chief hurried the army to advance north. Bennigsen even tried to defeat Lanna's corps, which had become separated from Napoleon's main forces, but the road, the movement along which made it possible to cover both Königsberg and the Russian border, just at Friedland crossed to the other side of the Alle River.

Napoleon did not miss the opportune moment, gathering all possible forces under Friedland. Instead of one corps, Bennigsen's army was opposed by the entire French army, although many researchers believe that Bennigsen mistook Lannes' columns for Napoleon's main forces.

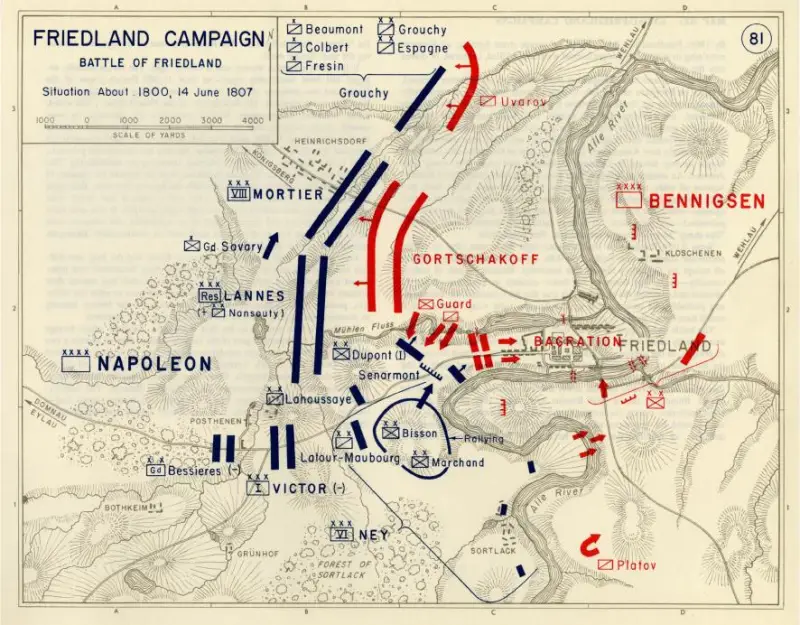

The general battle took place on June 2 (14), 1807. The positions of the Russian army were completely open, and they were cut in two by the Mühlenflus river, forming an impassable lake. The left flank was headed by P.I. Bagration, the right - by A.I. Gorchakov. Bennigsen hoped to strike at the French forces that had not yet fully arrived and attacked at dawn on June 2.

However, there was no talk of launching a decisive offensive - the French were preparing to attack with the approach of Ney’s corps and the guards cavalry. But the signal for the attack was given by the emperor only at five o'clock in the afternoon. Bagration's left flank took the main blow, and the Russian commander-in-chief did not lead the defense, suffering from stomach pain.

The Russians held out for three hours, after which, on Bennigsen’s orders, they began to retreat to the bridges. The road went through Friedland, on the streets of which, according to A. Ermolov, “the greatest disorder occurred due to constraint, which multiplied the effect of enemy artillery directed at the city.”

Bagration managed to lead his regiments to the other side along the set fire bridges, but Gorchakov’s right wing received the order to retreat when Friedland was already in the hands of the French, and the bridges were burned. They had to get out through fords; thousands died or were captured. Russian losses at Friedland amounted to 15-18 thousand - much less than at Eylau, what a defeat that can be.

After the victory, Napoleon entered Königsberg with Russian food warehouses, standing directly at the Russian border. Despite the fact that Bennigsen wrote to Alexander I that “... the army will fight as it has always fought,” things came to peace in Tilsit. Bennigsen was hastened to retire due to illness, although during the negotiations he received a compliment from Napoleon for Preussisch-Eylau.

The general, who, despite Friedland, could well count on a field marshal's baton for the campaign, left for his estate. Bennigsen did not try to appear in the capital - the world was now set against him.

It was the ability to make plans that returned Bennigsen to an active military career, although only four years later. In 1811, when the inevitability of a new war with France became clear, the general, who had become de facto something like the chief of the operational department of the army headquarters, drew up a plan of military action in the event of a new war with Napoleon.

Bennigsen's plan provided for a preemptive offensive by Russian troops, but another plan was adopted, and another one was being implemented. Bennigsen was considered as one of the candidates for the highest posts, although at first he was attached to the person of the emperor without specific assignments. The emperor was not in the army, even his brother Constantine was removed from there, nevertheless Bennigsen went to the 1st Army to M.B. Barclay de Tolly, who did not have the authority of commander-in-chief.

After the Battle of Smolensk, Bennigsen began to actively promote his candidacy for this post, but the emergency committee chose M.I. Kutuzova. And Leonty Leontievich was quite unexpectedly appointed as his chief of staff. Kutuzov, a famous master of intrigue, quickly recognized him as a dangerous rival and did not hesitate to play on his hostility towards the Hanoverian in his letters to the emperor.

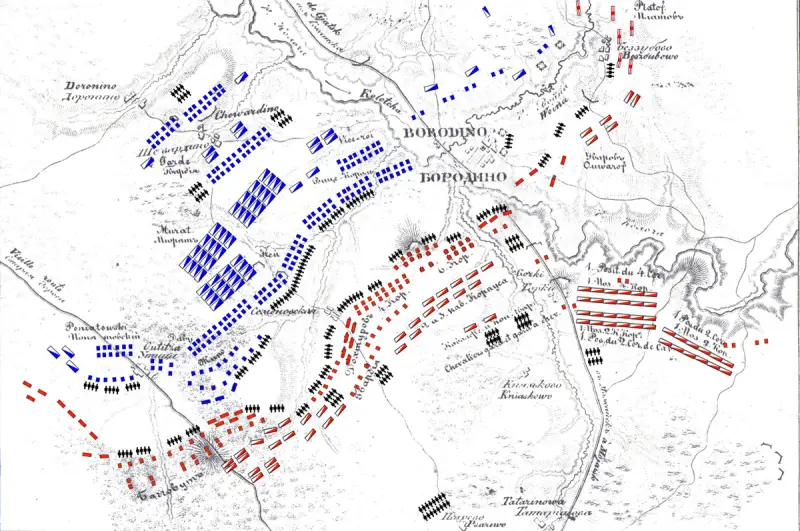

It is generally accepted that at Borodino Bennigsen thwarted the implementation of the almost brilliant plan of the commander-in-chief. The idea was supposedly to ambush the flank of the French columns attacking Bagration's flushes. The role of the ambush regiment was to be played by Tuchkov's 3rd Corps, which could have been completely cut off in its ambush by the advancing Polish 5th Corps of the Great Army.

Poniatowski's scouts established his location, and it was this that forced Bennigsen to place Tuchkov's two divisions in line with the main forces of the army, reinforcing them from the rear with a 10-strong column of militia and the Cossack regiments of Ataman Karpov.

In the most decisive battle, Bennigsen distinguished himself by his management and personal courage. As noted in the Russian Biographical Dictionary:

For his distinction at Borodino, Bennigsen was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, 1st degree. But it was not possible to work together with Kutuzov; already at the council in Fili, Bennigsen was with those who advocated a new battle, taking a position between Fili and Vorobyovy Gory and striking at the open right flank of the French. Kutuzov, in response, did not fail to remind him of the battle of Friedland, where similar maneuvers led Bennigsen’s army to disaster.

Bennigsen accompanied his messages to St. Petersburg about the abandonment of Moscow by accusing Kutuzov of indecisiveness and lethargy. The general, regularly supported by the British commissioner to the Russian army, General Sir Robert Wilson, insisted that it was necessary to strike the vanguard of I. Murat already at Krasnaya Pakhra. In addition, he was against the withdrawal of the army to the south, to the Kaluga road. Unlike Kutuzov, his chief of staff hardly expected that Napoleon would be forced to leave Moscow so quickly.

And the Russian commander-in-chief, in accordance with all the postulates of the then strategy and tactics, positioned the army with the ability to track any routes of movement of Napoleon’s army. But Bennigsen still achieved Kutuzov’s consent to a local attack against Murat on the Chernishna River. The Hanoverian personally led the right wing of the attackers, the left was commanded by General M.A. Miloradovich, who worthily replaced Bagration as the leader of the rearguard or vanguard of the army.

At Tarutino, the French were not defeated, it was not possible to cut off Murat, for which the chief of staff immediately blamed Kutuzov, who allocated clearly insufficient forces for the operation. Bennigsen was extremely irritated by the commander-in-chief's order to end the successful battle. Reporting to him about the outcome of the battle, he did not even get off his horse. He stated that the troops acted “with such correctness and order as can be seen in maneuvers alone,” while the field marshal was “too far from the scene of action” and did not want to bring reserves into the battle.

But Kutuzov did not plan a new Borodino at all, but Napoleon’s doubts about the combat readiness of his army became much stronger. The Military Council rejected the chief of staff's reproaches against Kutuzov, noting the uncoordinated actions of individual detachments and not the most skillful management of the operation. Having received Bennigsen’s accusatory letter from the military council, Kutuzov decided to get rid of his potential competitor.

The field marshal stopped receiving his chief of staff and soon managed to convince the emperor of the need to remove him from the army. The reason was given as “poor health and a leg wound received under Tarutino.” Surprisingly, immediately after the death of Kutuzov, the first person to be talked about as the new commander in chief was General Bennigsen.

But Alexander I did not dare to entrust more than a separate, so-called Polish army, to the Hanoverian. He would prefer a foreigner to play the role of commander-in-chief. General Moreau, expelled by Napoleon for participating in a conspiracy, was called from overseas, but he was immediately killed by the French core at the beginning of the Battle of Dresden.

Then there were rumors about the choice in favor of the Swedish Crown Prince Bernadotte, a former French marshal, and also a relative of Napoleon, who was married to Desiree Clary, the sister of the wife of Napoleon's brother Joseph, who unsuccessfully ruled in Spain. The intrigue ended when Austria joined the anti-French coalition, from where Alexander Pavlovich immediately called for the uninitiative Field Marshal Schwarzenberg. The Russian autocrat actually led all the allied forces until their entry into Paris.

And Bennigsen’s army, the so-called Polish, formed from troops located in the Duchy of Warsaw and Volhynia, was sent to join the main forces of the Allies only in August 1813. Having received orders to rush to Leipzig, where a decisive battle with Napoleon was planned, Bennigsen, with a slight delay, led the army to the right wing. His troops were joined by two Austrian corps and a Prussian brigade, and they drove the opposing French divisions to the walls of Leipzig.

For his distinction in the Battle of the Nations, the general was elevated to the rank of count, but was again left without the field marshal's baton. Then blocking the French corps of Iron Marshal Davout in Hamburg, Bennigsen failed to achieve practically nothing, openly fearing that the failure of the assault would deprive him of the opportunity to receive that very baton. In the end, everything was limited for him to the Order of St. George, 1st - the highest degree.

In peacetime, Bennigsen was not dismissed. And although it seemed to simply suggest itself, he was appointed commander of the 2nd Army with the main apartment located in Tulchin. The general, never inclined to organizational activity, openly neglected the leadership, which became known in the capital.

An audit was carried out led by P. D. Kiselyov, who reported to the emperor that Bennigsen was old and weak, “he doesn’t know the Russian language and Russian laws well, so he easily gets into trouble by signing orders and instructions prepared for him by self-interested persons.”

But only in 1818 did Leonty Leontievich ask to resign, and after the emperor, showering him with various signs of attention and respect, granted the request, he retired to the family estate in Hanover. He worked on memoirs about the war of 1806–1807, which were published in Russian Antiquity at the end of the XNUMXth century.

The memory of General Bennigsen as a commander is somewhat strange - he was, of course, a professional, of course, not a genius, but he once managed to withstand Napoleon. For another, this alone would be enough for glory, although it did not overtake all the winners of the great Frenchman.

Bennigsen’s contemporaries, including Russian generals and officers, were too strict towards him, but this is hardly due to his “foreign” origin. The Russian army had enough foreigners with respect and glory - Barclay alone is worth it.

Leonty Bennigsen died in 1826, outliving Kutuzov by thirteen years.

Information