The first “victor of the invincible” – cavalry general Bennigsen

Cavalry General Leonty Bennigsen. He was considered unlucky, but was the first to be called “the winner of the invincible,” and later he unsuccessfully competed with his peer M.I. Kutuzov. Bennigsen was a true professional who went through the wars of the era not only with glory, but sometimes with shame.

Bennigsen's biography, more a reference than a scientific one, was published in a number of sources, but we will try to look at him as the one who was the first to not yield to the invincible French general, first consul, and emperor. Moreover, in a series of publications in 2019 on the pages of VO for the 250th anniversary of Napoleon, the only gap remained an essay about General Bennigsen.

He served in Russia for almost half a century without receiving the field marshal's baton, but Bennigsen himself was most likely to blame for this. In Russia his name was Leonty Leontyevich, although Levin Theophilus von Bennigsen never mastered the Russian language properly.

The baron from an old Hanoverian family, who did not really like the Prussians, did a lot to save Prussia. Formally, he was born a British subject, since in the 18th century the king of England and Scotland was also the Elector of Hanover, but served Russia almost all his life.

Bennigsen served honestly, but was never recognized as an outstanding commander, although towards the end of his career he acquired an enviable reputation in secular salons. However, fortune was, one might say, indifferent to the Hanoverian mercenary, as, indeed, to most people like him.

For his high patrons, also participants in the conspiracy against Paul I, the disgrace turned out to be more serious than for Bennigsen. Apparently, it was no coincidence that he had no bright victories, and for a long time he did not receive independent command.

The first Polish campaign could have been a turning point in Bennigsen's career. Circumstances were such that Emperor Alexander I put him at the head of the army. Under the pressure of Napoleon, who was eager to place the victorious corps in winter quarters as soon as possible, she retreated across the Vistula, trying to cover the roads to Russia.

At the same time, it was necessary to defend Königsberg, the last great fortress in Prussia. The forces of the Russian army had to be constantly dispersed due to an acute shortage of provisions, but the French also had the same problems. However, they were clearly less prepared for winter, and the Russians also had Prussian land behind them, which was noticeably richer than Poland, devastated after uprisings and wars.

A variety of circumstances turned out to be in Bennigsen’s favor - and the first would be the illness of old Field Marshal Kamensky, because of which he later simply left the army. Here is the useless supervision on the part of Baron K. Knorring, who was safely dismissed three years earlier, and then Count Tolstoy.

And finally, how the army was unofficially commanded for several days by his eternal rival, General Buxhoeveden. He, not forgetting Austerlitz's nightmare, simply avoided supporting Bennigsen's corps at Pultusk. Near this town, 40 thousand of Bennigsen were attacked by the corps of Marshal Lannes, whose number barely reached 30 thousand.

At first, Bennigsen was unable to prevent the French from crossing the Vistula and even retreated to Ostroleka, but due to the inaction of the enemy, he again took a good position there. The Russians managed to withstand the blow of Lannes, who threatened that Napoleon would cut off the retreat routes for all other troops.

The French were repulsed, and Bennigsen immediately sent a dispatch to St. Petersburg with a message about the victory over Napoleon himself. Even then, someone hastened to call the general “the conqueror of the invincible.” The issue of appointing a new commander-in-chief was resolved by itself, and Bennigsen was awarded the Order of St. George, 2nd degree and 5 chervonets.

However, after the failure of Lannes, the French bypassed the Russian army from the other flank - at Golymin, forcing Bennigsen to retreat. Retreating through Ostroleka, the new commander-in-chief, still awaiting his appointment, burned the most important bridge, thereby not so much preventing pursuit by Napoleon as forcing two divisions from Buxhoeveden’s corps to join him.

A contemporary recalled:

The unrest was especially great in Bennigsen's corps. Brave to the point of heroism, he did not care about subordination and army control. In his main apartment, garrison service was neglected. Guards were rarely posted at the houses he occupied. In Rozhan, looters broke into Bennigsen’s rooms three times, even into his office, and instead of strictly punishing him, he calmly said: “Drive out the scoundrels!”

There is too much evidence from contemporaries, right up to Alexander I himself, who say that Bennigsen lost control of the army. Due to non-payment of wages, it came to charges of collusion with suppliers. However, circumstances again worked out in favor of the Hanoverian mercenary.

Napoleon did not pursue the Russians, stopped at Tykochin and returned to Warsaw, placing his corps in winter quarters at great distances from each other. Bernadotte's regiments stood at Elbing, Ney's - stretched along the Alla River. General Buxhoeveden suggested taking advantage of this.

The Russian vanguards even set out for Johannisburg on January 11 (December 30, O.S.), 1807, but on the same day a courier from Emperor Alexander finally arrived with a rescript appointing Bennigsen as commander-in-chief. General Buxhoeveden was sent as governor to Riga with a recall from the army. Out of resentment, he even challenged Bennigsen to a duel, which the latter wisely avoided.

But he did not abandon the offensive launched by his predecessor, because he believed that, having an army of 150 with 624 guns, he could not limit himself only to protecting the borders and covering Koenigsberg. However, the beautiful plan to stand with the main forces between the corps of Bernadotte and Ney in order to defeat one of the marshals fell through due to the slowness of the exhausted Russian troops.

Bernadotte escaped from the blow, and Napoleon decided to resume active operations. The Emperor hoped to bypass Bennigsen's left flank, cut him off from the Russian border and throw him back to the Vistula. The Russian headquarters managed to figure out this plan, and Bennigsen began to pull forces to Yankov, where only Lestocq’s Prussian corps was late.

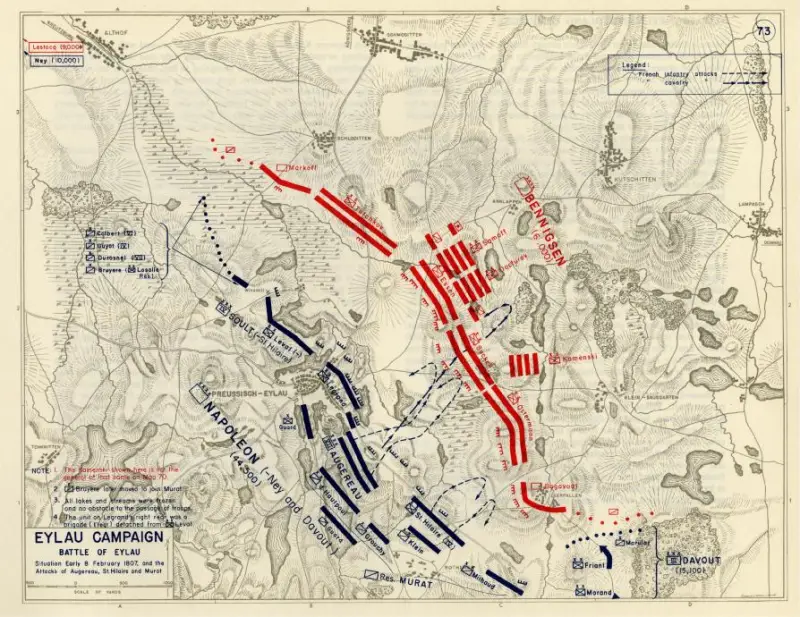

The corps of four Napoleonic marshals had already concentrated against the main forces of the Russian army, and the position, which practically did not defend Königsberg, had to be abandoned after several skirmishes. The army, under the cover of Prince Bagration's strong rearguard, slowly retreated to Preussisch-Eylau.

The battle itself - the first of Napoleon's defeats, or rather, Napoleon's draw in a field battle - is the subject of a separate chapter from the story of Napoleon's 12 defeats (They defeated Napoleon. Heroes of Eylau). Here we will limit ourselves only to the main points that characterize the role of the Russian commander-in-chief in the events of February 7 and 8, 1807.

And again we recognize the professionalism of Bennigsen, like most of his subordinates, as well as the stamina and valor of the Russian soldiers. Victory did not go to Napoleon not only due to the prevailing conditions and a series of accidents, but because, among other things, the Russians and Prussians did not make serious mistakes. As is known, the great Corsican did not forgive them.

It must be admitted that Bennigsen missed a lot of opportunities to concentrate maximum forces on the battlefield, although he stubbornly pulled Lestocq’s 9-strong Prussian corps towards him. As a result, out of an army of 150 thousand people, less than half took part in the battle.

However, Napoleon managed to gather only a little more into one fist near Prussian Eylau. And he, and his marshals, and their troops in those days were not able to show all that they were capable of. But the Russian commanders were not inferior to themselves.

At first, Barclay, having a detachment five times smaller than the French vanguard, held out until darkness in the battle at Gough. The French then justified their failure by saying that it was very difficult to advance in deep snow. It was also not easy for the Russians; they retreated to Landsberg slowly and in complete disorder, but the main thing is that “the army was saved from a surprise attack.”

Then Bagration, a true genius of vanguard and rearguard combat, fought with almost the entire French army in front of Preussisch-Eylau and for the city itself. Prince Peter's detachment did everything so that the army could survive the general battle. However, the commander-in-chief actually removed the general from participating in it, holding Bagration responsible for the fact that on the night of February 8, Eylau fell into the hands of the French.

What caused this - confusion in the troops or erroneous orders of General Markov - is still a subject of debate among historians. Another thing turned out to be more important - the loss of a forward position in the city actually played into the hands of the Russians the next day. Coming out of the narrow defile, moreover, in a snowstorm, the French infantry immediately came under fire from Russian batteries located on the ridge north of Eylau.

Under other conditions, they might have been answered by French cannons from the heights outside the town, but a snowstorm rendered their fire ineffective. But Russian grapeshot struck Augereau’s corps almost point-blank. But before this, the diversionary attack by Soult’s corps against the lines and columns of Tuchkov and Essen had also failed poorly.

After about an hour, Augereau's corps, marching in a snowstorm, almost in full strength moved to the right and came under heavy fire from 70 Russian cannons from the flank. The divisions of Desjardins and de Bierre were driven back by a coordinated counterattack of grenadiers and cavalry, which almost broke through to the French headquarters on the outskirts of the city.

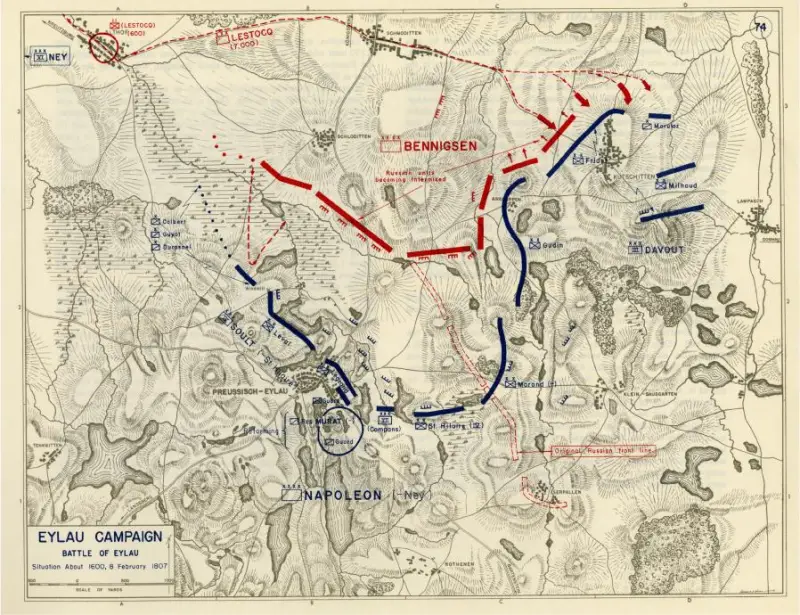

Napoleon was forced to save Augereau from defeat by a massive attack of 75 squadrons of Murat's cavalry. However, the Russians withstood both the pressure of Murat and the attacks of Davout’s corps. The Russian left flank retreated, losing first Klein-Sausgarten, and then Auklappen and Kuchitten. But the French did not succeed in breaking through, although the Russian positions bent at a right angle.

It is unlikely that any other army would have been able to withstand this situation, especially since Ney’s corps could threaten it from the rear. And after three companies of horse artillery were brought up from the right wing, on the orders of the artillery commander Kutaisov, and their 36 cannons opened fire on Davout’s columns from close range, it became clear that the Cannes planned by Napoleon would not exist for the Russians.

At this time, there was no longer a commander-in-chief at headquarters - Bennigsen himself claims in his memoirs that he personally went to meet Lestocq’s corps, with which he expected to respond to Davout’s envelopment.

Many of the participants in the battle, including Ermolov, later wrote that their commander considered the battle lost and was the first to “begin to retreat.” But how, in this case, should we evaluate the arrival of the Prussians and the powerful counterattack of Lestocq?

There are witnesses who saw how Bennigsen, together with the Prussian general, observed the advance of cavalry columns between Schloditten and Kuchitten. Bennigsen still did not win, and the battle is considered to be a draw, even in France. But the impression from Eylau was very strong.

The Russian commander did not do anything supernatural; the fact that he personally met Lestocq’s Prussian column should not be considered a special achievement of the commander. However, could you imagine Napoleon setting off to meet Pears near Waterloo?

No, the Emperor at Waterloo only limited himself to the famous reprimand to Marshal Soult, who replaced the irreplaceable Berthier at the head of his staff. At the decisive moment of the battle, Napoleon asked the Duke of Dalmatia what news about Grouchy, and, having received the answer that the chief of staff had sent a courier there, irritably said to him: “Berthier would have sent four!”

The Russians drove back Davout, brought Napoleon's cavalry into a terrible state, almost completely destroyed Augereau's corps and upset the ranks of the guard. And they continued to stand like a wall at their guns behind the same ridge where they met the first onslaught of the enemy. However, like Kutuzov five years later, after Borodino, Commander-in-Chief Bennigsen gave the order to retreat.

Leaving the roads to Russia in the already securely secured rear. Most likely, Bennigsen feared a blow to the rear from Ney’s corps, which could well have been supported by Bernadotte. However, Napoleon chose not to pursue the battered Russian army, given the heavy losses and extreme exhaustion of the troops.

But this did not stop his traditional victorious reports in the famous “Bulletin”, which few people believed even in France. Why after Eylau neither Bennigsen nor Emperor Alexander thought about concluding peace is not for us to judge, but in the summer campaign Napoleon will defeat his offender at Friedland and will actually dictate to “friend Alexander” the terms of the Peace of Tilsit.

The ending should ...

Information