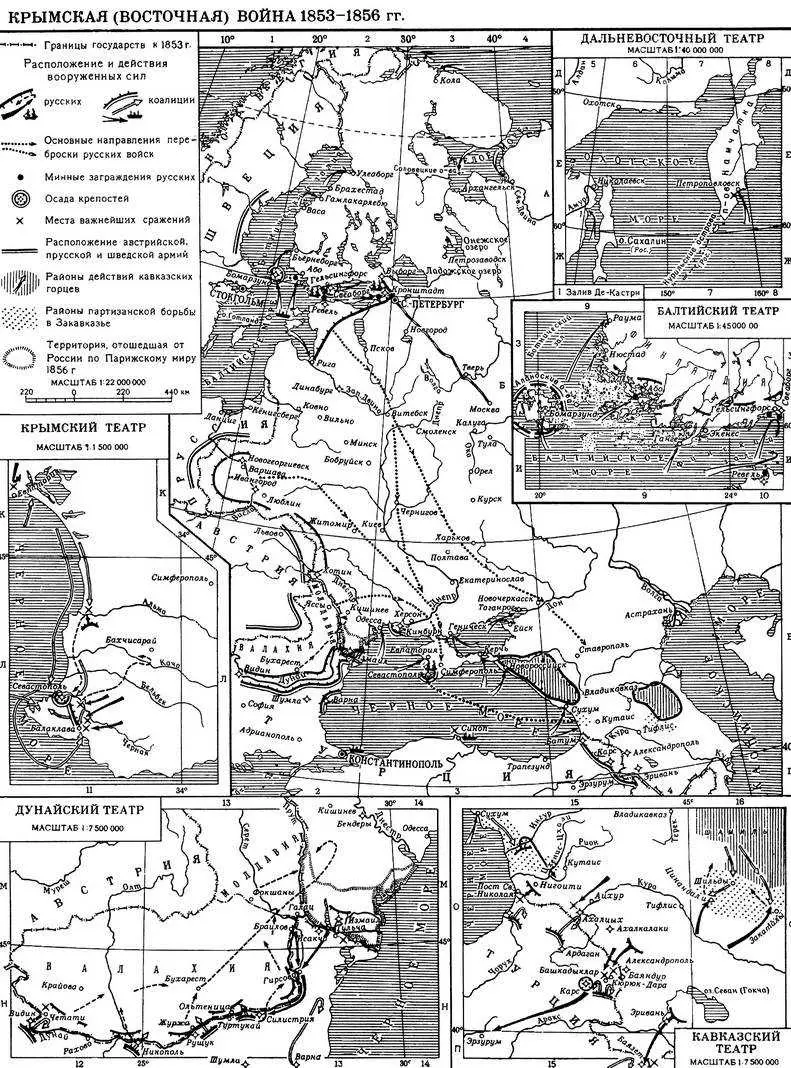

The heroism of Russian troops and the failure of the high command in the Danube campaign

Maksutov V.N. Battle of Chetati

General situation

On June 1, 1853, St. Petersburg announced a memorandum on severing diplomatic relations with the Porte. After this, Tsar Nicholas I ordered the Russian army to occupy the Danube principalities (Moldova and Wallachia) subordinate to Turkey “as collateral until Turkey satisfies the fair demands of Russia.” On June 21 (July 3), 1853, Russian troops entered the Danube principalities.

The Ottoman Sultan did not accept Russia's demands for the right to protect Orthodox Christians in Turkey and nominal control over holy places in Palestine. Hoping for the support of the Western powers, the Ottoman Sultan Abdulmecid I on September 27 (October 9) demanded the cleansing of the Danube principalities from Russian troops within two weeks.

Russia did not fulfill this ultimatum. On October 4 (16), 1853, Türkiye declared war on Russia (How Türkiye opposed the “gendarme of Europe”). On October 20 (November 1), Russia also declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The Eastern (Crimean War) began.

Sovereign Nikolai Pavlovich, who until that time had quite successfully led the foreign policy of the Russian Empire, in this case made a strategic mistake (How Nikolaev Russia fell into the trap of the Crimean War). He thought that the war would be short and small, ending with the complete defeat of the Ottoman Empire, which was not ready for war and was greatly degraded, and would not be able to withstand the Russian troops in the Balkans and the Caucasus, and the Russian the fleet in the Black Sea. Then St. Petersburg will dictate the terms of peace and take what it wants.

Everything would have happened this way if not for the intervention of Western powers. Nicholas I made a mistake in assessing the interests of the great Western powers. And the Russian Foreign Ministry, headed by the Anglomaniac Karl Nesselrode, completely failed diplomatic intelligence. Russian embassies in Western Europe voiced a “beautiful” picture that did not correspond to the harsh reality - the Russian Empire had no partners and allies other than its army and navy.

England did not stand aside, on the contrary, pretending to be interested in Russian proposals for Turkey, lured the Russians into a trap, entered into an anti-Russian coalition with France, and put together an anti-Russian alliance. During this period, the French Emperor Napoleon III was looking for an opportunity to carry out a foreign policy adventure that would return France to its former glory and create the image of a great ruler for him. A conflict with Russia, and even with the full support of England, seemed to him a tempting proposition, although the two powers had no fundamental contradictions.

The Austrian Empire, which had long been an ally of Russia and owed its existence to the Russians, took an openly anti-Russian position after the Russian army under Paskevich defeated the Hungarian rebels in 1849.

The only possibility of victory is a blitzkrieg in the Balkans

Nicholas’s confidence in Turkey’s imminent surrender had a very negative impact on the combat effectiveness of the Danube Army. Her decisive and successful offensive could disrupt many of the enemy’s plans. Austria, during the victorious offensive of the Russian army in the Balkans, where it would have been supported by the Bulgarians and Serbs, was afraid to put pressure on St. Petersburg. And England and France simply did not have time to transfer troops to the Danube front by this time. The Turkish army on the Danube front consisted half of the militia (redif), which had virtually no military training and was poorly armed.

Decisive strikes by the Russian army on the Danube, the Caucasus, plus the destruction of the core of the Turkish fleet by Nakhimov (“Hurray, Nakhimov!” Destruction of the Turkish squadron in the Battle of Sinop) could bring Turkey to the brink of a military-political catastrophe.

However, the Russian corps, which under the command of Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov crossed the Prut in the summer, did not launch a decisive offensive. The command did not dare to undertake such an attack. St. Petersburg expected that Türkiye was about to throw out the white flag.

The army began to gradually disintegrate. Thefts became so widespread that they began to interfere with the conduct of military operations. The military officers were greatly irritated by the outrageous rampant predation of the commissariat and the military engineering unit. Particularly annoying were the pointless buildings that were completed before the retreat began.

Soldiers and officers began to understand that banal theft was taking place. The troops quickly felt that the high command itself did not know exactly why it brought Russian troops here. Instead of a decisive offensive, the corps stood idle. This had the most negative impact on the combat effectiveness of the troops.

In the pre-war period, Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich advocated a bold breakthrough through the Balkan Mountains to Constantinople. The advancing army was to be supported by the landing force that was planned to land in Varna. If successful, this plan promised a quick victory and a solution to the problem of a possible breakthrough of the European squadron from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea.

However, Field Marshal General Ivan Fedorovich Paskevich, who was the sovereign’s closest comrade, opposed such a plan. The field marshal did not believe in the success of such an offensive. Paskevich did not want war at all, sensing great danger at its beginning.

Paskevich was distinguished by a sober view of Russia and its order; he himself was an honest and decent person. He knew that the empire was sick and should not fight the Western powers. He was much less optimistic about the power of Russia and its army than the tsar.

Paskevich knew that the army was affected by the theft virus and the presence of a caste of “peacetime generals.” In peacetime they were capable of convincingly holding parades and parades, but during the war they were indecisive, lacking initiative, and lost in critical situations. Paskevich feared the Anglo-French alliance and saw it as a serious threat to Russia. Paskevich did not trust either Austria or Prussia; he saw that the British were pushing the Prussians to capture Poland.

Paskevich was almost the only one who saw that Russia was facing a war with the leading European powers and that the empire was not ready for such a war. He believed that the result of a decisive offensive in the Balkans could be an invasion of the Austrian and Prussian armies, the loss of Poland and Lithuania.

Not believing in the success of the war, Paskevich changed the earlier war plan to a more cautious one. Now the Russian army had to occupy the Turkish fortresses on the Danube before advancing on Constantinople. Paskevich proposed to fight the Ottoman Empire with the help of Christian peoples who were under the Ottoman yoke.

As a result, the caution of the high command and the complete failure of St. Petersburg on the diplomatic front created extremely unfavorable conditions for the Danube Army from the very beginning. The army, sensing the uncertainty at the top, was marking time. Paskevich also did not want to give up significant formations from his army (in particular, the 2nd Corps), which was stationed in Poland to strengthen the Danube Army. He exaggerated the extent of the threat from Austria.

Portrait of I. F. Paskevich by Jan Ksaveri Kanevsky (1849 year)

Correlation of forces

For operations in the Danube principalities, the following were assigned: the 4th Corps (more than 57 thousand soldiers) and part of the 5th Infantry Corps (more than 21 thousand people), as well as three Cossack regiments (about 2 thousand people). The army's artillery fleet consisted of about 200 guns. In fact, the entire burden of the fight against the Ottomans fell on the Russian vanguard (about 10 thousand people). The Russian vanguard resisted the Turkish army from October 1853 until the end of February 1854.

An army of 80 thousand was not enough to firmly conquer and retain the Danube principalities for the Russian Empire. In addition, Mikhail Gorchakov scattered his troops over a considerable distance. Also, the Russian command had to take into account the danger of a flank threat from the Austrian Empire. By the autumn of 1853 this danger became real, and in the spring of 1854 it became predominant. The Austrians were more feared than the Ottomans. The Russian army, fearing an attack from Austria, first went on the defensive and then left the Danube principalities.

Moldavian and Wallachian troops numbered about 5–6 thousand people. Local police and border guards numbered about 11 thousand people. However, they could not provide significant assistance to Russia. They were not hostile to the Russians, but they were afraid of the Ottomans and did not want to fight. In addition, some elements (officials, intelligentsia) in Bucharest, Iasi and other cities were oriented towards France or Austria. Therefore, local formations could only perform police functions. Gorchakov and the Russian generals did not see much benefit from local forces and did not force them to do anything. In general, the local population was not hostile to the Russians; they did not like the Ottomans here. But the local residents did not want to fight.

The Ottoman army numbered up to 150 thousand people. The regular units (nizam) were well armed. All rifle units had rifled rifles, some of the cavalry squadrons already had rifles, and the artillery was in good condition. The troops are trained by European military advisers.

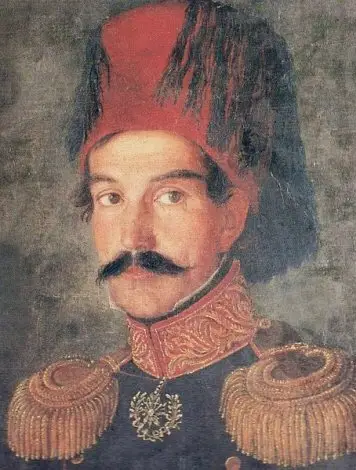

The weak point of the Turkish army was the officer corps. In addition, the militia (almost half of all military forces) were armed and trained much worse than the regular units. Also, the Turkish commander-in-chief Omer Pasha (Omar Pasha, Serbian origin Mikhail Latas) had a significant number of irregular cavalry - bashi-bazouks. Several thousand bashi-bazouks performed reconnaissance and punitive functions. They used terror to suppress any resistance from the local Christian population.

Omer Pasha was not a great commander; he mainly distinguished himself in suppressing uprisings. At the same time, he cannot be denied some organizational skills, personal courage and energy. But his success on the Danube front was more connected with the mistakes of the Russian command than with the talent of the commander. Moreover, the Turkish commander-in-chief was not even able to take full advantage of them.

The Turkish army was helped by many foreigners. At the headquarters and headquarters of Omer Pasha there were a significant number of Poles and Hungarians who fled to Turkey after the failures of the uprisings of 1831 and 1849. These people often had a good education, combat experience, and could give valuable advice. Their weakness was hatred of Russia and Russians. Hatred often blinded them, forcing them to mistake their desires for reality. They greatly exaggerated the weaknesses of the Russian army. In total, there were up to 4 thousand Poles and Hungarians in the Turkish army. More useful were the French staff officers and engineers who began to arrive at the beginning of 1854.

Ottoman commander of Serbian origin Omer Lutfi Pasha (Omer Pasha, Omar Pasha, real name Mikhail Latas). At the beginning of the Crimean War, Omer Pasha commanded the Turkish army operating on the Danube line

The situation on the Danube and the Balkans

After occupying the principalities, Gorchakov left the entire old administration of the principalities in place. This was a mistake. This “liberalism” could no longer improve anything. England and France were heading towards a break with Russia, and Turkey was ready to fight. In St. Petersburg this was not yet understood. The former Moldavian and Wallachian officials retained the threads of government, the court, and the city and village police. And it was hostile to Russia (unlike ordinary people). As a result, the Russian army turned out to be powerless against the vast intelligence and spy network that acted in favor of Turkey, Austria, France and England.

St. Petersburg tried to play the national and religious card - to raise Serbs, Bulgarians, Greeks and Montenegrins against the Ottomans. However, here he encountered several serious problems.

Firstly, in the previous period, Russia advocated legitimism and was extremely suspicious of any revolutionary, national liberation movements and organizations. Russia simply did not have secret diplomatic and intelligence structures that could organize such activities in the Porte's possessions.

Emperor Nicholas himself had no experience of such activities. And starting everything literally from scratch was a pointless exercise. A long preliminary and preparatory work was necessary. In addition, in Russia itself there were many opponents of such a course at the top. In particular, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which did not want international complications, opposed Nikolai’s initiative.

Secondly, England and Austria had secret networks in the Balkans, but they were opponents of pro-Russian movements and did not want uprisings on the territory of the Ottoman Empire at that time. Austria could have played a great role in rousing the Christian and Slavic population, but it was opposed to Russia.

Thirdly, the Christians of the Balkans themselves from time to time raised uprisings, which the Ottomans drowned in blood, but during this period they were waiting for the arrival of Russian troops, and not for some hints that matters needed to be taken into their own hands. The fantasies of the Slavophiles that there is a Slavic brotherhood, that the Serbs and Bulgarians themselves can throw off the Turkish yoke, only with the moral support of Russia and immediately ask for the hand of the Russian Tsar, were far from reality.

Fourthly, the Turkish authorities had extensive experience in identifying dissatisfied people and suppressing uprisings. Numerous units of Turkish police, irregular troops and army were located in the Slavic regions.

Portrait of Prince M. D. Gorchakov. Artist E. I. Botman

First fights. Oltenica

Initially, Russian troops stationed in Bucharest and its surroundings. A small detachment was sent to Mala Wallachia, its headquarters was located in Craiova. Initially, the forward detachment was commanded by General Fischbach, then he was replaced by General Anrep-Almpt. In the Russian avant-garde there were about 10 thousand people.

The Danube Army was unlucky with its commander. Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov successfully fought in the Patriotic War of 1812, took part in the foreign campaigns of the Russian Army of 1813–1814, and in the Russian-Turkish War of 1828–1829. Participated in the suppression of uprisings in Poland and Hungary. But Gorchakov by nature was not a decisive and independent person.

For 22 years he served as chief of staff under Paskevich in Warsaw and completely lost the habit of taking responsibility for his actions and the ability to think independently. He completely immersed himself in administrative work and became the unquestioning executor of Paskevich’s will. Gorchakov was deprived of his leadership abilities and Paskevich’s ambivalent attitude towards the war and the Danube campaign completely confused him.

Gorchakov was a smart man and a good performer, but not a commander who could independently solve strategic problems. The general constantly looked back at St. Petersburg and Warsaw. Emperor Nicholas wanted a decisive offensive, but did not know whether it was possible, and was waiting for Paskevich’s clear opinion.

The Polish governor, Field Marshal Paskevich believed that Austrian intervention in the war was inevitable, and this would lead the Danube Army to the brink of disaster. Therefore, he believed that it was impossible to attack, it was better to withdraw the troops back to Russia. However, he did not want to directly tell Nicholas that the war had already been lost on the diplomatic front, and Russia would have to fight a coalition of European powers. At the same time, Paskevich wanted not he, but Gorchakov himself, to impress this on the tsar and propose the evacuation of troops from the Danube principalities. In such a situation, Gorchakov was completely at a loss and confused. This confusion and indecision spread to the headquarters, and after the first failures, to the entire army.

While the Russian command doubted and the army was marking time, the Turks themselves began to take active action. The Ottomans occupied an island on the Danube, crossed the river, calmly captured Kalafat and fortified it. This Turkish bridgehead later became a source of problems.

On October 20 (November 1), 1853, the Ottomans crossed from Turtukay to a large wooded island and began to threaten the village of Oltenica. A report about this was sent to the commander of the 4th Corps, General Dannenberg. He considered that there was no threat from the crossing of the “twenty Turks”. On October 21, the Ottomans crossed the river in large forces (8 thousand soldiers) and captured the Oltenice quarantine (port facility) and began to build fortifications. In addition, Omer Pasha had a large reserve at Turtukay - 16 thousand people. The Cossack post could not resist the enemy's crossing.

On October 22, a Russian detachment under the command of General Soimonov (one infantry brigade, 9 squadrons and hundreds with 18 guns) from the 4th Corps took a position near Stara Oltenica. The Russian soldiers were inspired, finally the first real thing. One of the participants in the battle recalled that the night was noisy: “... loud talking, laughter, inspired shouts, native daring songs - everything merged into a general roar that stood over our bivouac.” On the morning of October 23, the Russian brigade, despite the enemy's superiority in numbers, stormed the Turkish fortifications.

The beginning of the battle was difficult: the Turks managed to build field fortifications with batteries. The Ottomans also had artillery on the elevated right bank of the Danube and could simply shoot Russian troops. The area was open. In addition, the Turks also placed a battery on the island and could attack the Russian positions on the flank. However, the Russian soldiers were not embarrassed. They behaved like battle-hardened veterans. Russian troops went on the attack several times, although the enemy simply bombarded them with shells and bullets.

As a result, the Ottomans wavered and began to leave quarantine, take guns from the rampart, and board boats. Russian soldiers burst into the first enemy trench. And then came an unexpected order from General Dannenberg to retreat.

At the last moment, the Russian victory turned into defeat. Russian troops lost about 1 thousand people in the battle near Oltenica, the Turks - 2 thousand people. The Ottomans did not develop their success, burned the quarantine and returned to the right bank of the Danube.

Battle of Oltenitz. Hood. D. August.

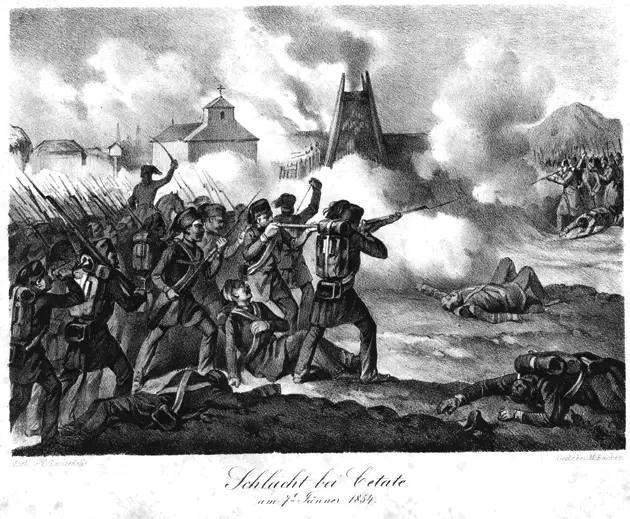

Ottoman advance at Çetati

After Oltenica, the Russian army finally lost its understanding of what it was doing in the Danube principalities. Gorchakov continued to send ambiguous and vague orders, like: “Kill, but do not allow yourself to be killed, shoot at the enemy, but do not be exposed to his fire...”. The commander of the advance detachment, General Fischbach, turned out to be even more “talented” than Dannenberg, and he was eventually removed due to complete incompetence, replacing him with Count Anrep-Elmpt.

It didn't get any better. Anrep-Elmpt, who during the Russian-Turkish War of 1828–1829, the Polish uprising of 1831 and the Caucasian War showed himself to be a good commander, did not show his previous talents in the Eastern War. The relatively small detachment of Anrep-Elmpt was dispersed at a distance of 30 versts and completely lost its striking power.

Part of this detachment was located near the village of Chetati. Here, under the command of the commander of the Tobolsk Regiment, Colonel Alexander Baumgarten, there were 3 battalions of the Tobolsk Regiment, 6 guns of light battery No. 1 of the 10th Artillery Brigade, 1 squadron of the Alexandria Hussar Field Marshal Prince of Warsaw Count Paskevich-Erivan Regiment, 1 hundred of the Don Cossack Regiment No. 38. In total, the Russian detachment numbered 2,5 thousand people.

On December 19 (31), Baumgarten, with the forces of one battalion and a platoon of hussars with two guns, repelled an attack by a 2-strong enemy cavalry detachment. It must be said that Alexander Karlovich Baumgarten was a real military officer who had served in the Caucasus, where he was awarded the Order of St. Anne, 4th degree, with the inscription “For bravery.”

On December 25, 1853 (January 6, 1854), the commander of the Tobolsk regiment received news of the advance of large enemy forces. As it turned out later, the Ottomans were advancing in large forces - 18 thousand soldiers. A stubborn battle broke out. Baumgarten's detachment repelled several enemy attacks. But the forces were unequal, and the reserves were quickly depleted. The situation became critical. In addition, the Ottomans occupied the road that led to Motsetsen, where another Russian detachment was located under the command of the brigade commander Bellegarde.

Baumgarten, not seeing the possibility of keeping Cetiat behind him, began to retreat. But the road was closed by enemy cavalry, which advanced 6 horse guns, opened fire on the Russian troops. The brave regimental commander headed the 3 th battalion and overturned the Turkish cavalry with a bayonet attack. The offensive was carried out with such decisiveness and speed that the Ottomans lost two guns.

The Turks quickly recovered and again began to press on the Russian detachment. Baumgarten, outside the village of Chetati, took a new position and began to repel enemy attacks. Russian infantry fired volleys at enemy forces at a distance of 50 steps. The Ottomans fought bravely and broke through to the Russian lines. Hand-to-hand combat began. The enemy was driven back again, and 4 guns and a charging box were captured.

During the retreat, the Turkish cavalry fell into a ravine, and the Russians, pursuing the enemy, rushed there. Baumgarten decided to occupy the ravine to improve his defensive capabilities. In front of him there was a ditch and a rampart that interfered with the movement of the infantry. There was no bridge or descent; it was a long way around. Russian ingenuity and self-sacrifice came to the rescue.

Private of the 12th company Nikifor Dvornik jumped into the ditch, stood across it and, bending down, making himself like a bridge, shouted to his friends: “Cross over me, guys! It will be done soon!” So he let about forty people pass through him. Then he was pulled out. Russian soldiers rushed at the Ottomans and occupied the ravine. The Turkish cannons were riveted, the carriages were chopped up.

This local success temporarily improved the position of the Russian detachment. The Turkish troops, who had a huge numerical superiority, continued their attacks. The enemy installed several batteries and began heavy shelling. The Russian artillery was already exhausted in this unequal struggle. Baumgarten was wounded, but continued to lead the detachment. The Turkish command began to advance several fresh battalions in order to end the resistance of a small Russian detachment with one decisive blow.

Hero of the Crimean War, General Alexander Karlovich Baumgarten (1815–1883)

Defeat the enemy

At this moment, when hopes were almost extinguished, salvation came. The Ottomans were suddenly overcome with confusion. They stopped artillery fire and began to retreat. The sounds of battle were heard in the Turkish rear. It was the Odessa regiment from Karl Bellegarde’s detachment that came to the rescue. The Odessa regiment immediately entered the battle and, breaking through the Turkish trenches, suffered significant losses. However, at the cost of heavy losses, he broke through the Turkish defense and rescued Baumgarten’s dying detachment.

In the evening, when the Ottomans received news of the approach of the main forces of General Anrep-Elmpt, they hastily retreated from Cetati to Kalafat. Russian troops pursued the enemy for some time and killed many. Russian troops (in the detachments of Baumgarten and Bellegarde there were up to 7 thousand people) lost more than 2 thousand people in this battle. Turkish losses were higher.

The Russian army won.

The Battle of Chetati left many questions. None of the participants in the battle doubted that Gorchakov and Anrep-Elmpt had made a big mistake by scattering their forces over a long distance. In addition, Baumgarten’s detachment did not have cavalry, which the command dispersed to completely unnecessary guard posts, in places where there was no enemy. But there was no cavalry in the dangerous area.

Anrep was very late in providing help, and the opportunity to completely defeat the enemy troops was missed; the Ottomans retreated to Kalafat. The sounds of battle reached the location of Anrep’s forces, but he hesitated for hours. He decided to celebrate the Feast of the Nativity of Christ. A long prayer service kept all the authorities in the church. At this time, the soldiers were toiling and did not understand what was happening. The soldiers said to each other: “They beat our people, but we pray like old women, instead of helping our own! This is not good, brothers, God will not forgive us for this!”

After the troops set out, Anrep-Elmpt with fresh forces did nothing to turn the battle into a complete defeat of the enemy. The defeated enemy retreated quite calmly. The Chetat affair could have been turned into an operational success in this direction. But the Ottomans were allowed to leave.

This is how the first period of the Danube campaign ended pitifully. He showed how even a good army, which at the beginning of the war was ready to crush the enemy, absolutely cannot do anything (except die heroically) if the high command is not self-confident, does not show the will and is not ready to solve strategic problems. Russian troops engaged in battle with superior enemy forces and in one case were deprived of a victory, which was turned into defeat.

At Chetati, the victory was incomplete; due to command errors, Russian troops missed the opportunity to inflict a decisive defeat on the enemy, which would have had far-reaching consequences. Ordinary soldiers and officers again showed steadfastness and courage in the battles of Oltenitz and Cetati, confirming their highest fighting qualities. But things were very bad with the command.

Battle of Chetati. Austrian artist Karl Lanzedelli

Information