Pyotr Rumyantsev in the Seven Years' War

P. A. Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky in a portrait by an unknown artist, late XNUMXth century.

В previous article we talked about the origin and early life of Pyotr Rumyantsev, the beginning of his military career. This article ended with a short story about the beginning of the Seven Years' War and the Battle of Gross-Jägersdorf. Today we will continue the story about this commander.

1758 year

So, almost immediately after the victory in the battle of Gross-Jägersdorf, the Russian army began to retreat to winter quarters. Its new commander was Willim Fermor.

Willim Villimovich Fermor in the portrait of Alexei Antropov

In January 1758, lieutenant general and division commander Pyotr Rumyantsev and General Saltykov, who was acting together with him, went to East Prussia, occupying Königsberg. In August, the Russians besieged the Küstrin fortress, and the Prussian king himself hastened to the rescue of the garrison. On August 14, a new battle between the Russian and Prussian armies took place near the village of Zorndorf, in which Rumyantsev did not take part. The battle lasted all day and, despite heavy losses on both sides, did not reveal a winner. The next day, Frederick withdrew his army to Saxony, and the Russians retreated to the Vistula and further to Pomerania. Rumyantsev, who was tasked with covering the movement of the main troops, at the head of 20 dismounted dragoon and horse-grenadier squadrons, managed to hold back the 20-strong corps of the Prussian army in the battle at Pass Krug.

1759 and the Battle of Kunnensdorf

A.E. Kotzebue. "Battle of Kunnersdorf August 1, 1759"

The following year, the Russians changed their commander again - he became Chief General Pyotr Semyonovich Saltykov, who had previously fought in the army of Minich, and in the recent war with Sweden - under the command of Lassi and Keith, was awarded a gold sword with diamonds. At that time he was over 60 years old and did not look at all militant; A. Bolotov described him this way in his memoirs:

Pyotr Saltykov in the portrait of Pietro Rotari

In July 1759, Russian troops numbering up to 40 thousand people moved towards the Oder, hoping to unite there with the Austrian allies. On July 12 there was a clash with the Prussian corps of General Wedel. He had only 28 thousand soldiers at his disposal, but Russian troops were attacked on the march. The battle near the village of Kai lasted about 5 hours, and in the end Wedel was forced to retreat. And on August 3, 1759, Russian and Austrian troops united at Frankfurt-on-Oder. On August 10, Frederick II approached from the south and positioned his army near the village of Kunersdorf. A feature of the position was a large ravine in front of the front of Russian and Austrian troops. Rumyantsev's division found itself in the center - on the Big Spitz hill.

1 (12) August 12, 1760 at 11 o'clock, Frederick II began the Battle of Kunersdorf with artillery strikes on Russian positions. Then 8 battalions of Prussian grenadiers managed to capture the Mühlberg hill, forcing the Russian left-flank units defending it to retreat beyond the ravine. If the Prussian king had stopped there, the Russian-Austrian troops would probably have been forced to retreat the next day. However, Frederick decided to achieve complete victory and continued the battle. But the attacks of the Prussian infantry, supported by Seydlitz’s heavy cavalry (which acted precisely against Rumyantsev’s division), were ineffective. And then the Arkhangelsk and Tobolsk regiments, whose attack was led by Rumyantsev, and the Austrian cavalry of General Kolovrat, attacked the tired Prussians who had suffered heavy losses. The Prussians fled, abandoning a significant part of their artillery; Frederick II was shell-shocked and lost his cocked hat, which can now be seen in the Hermitage.

Tricorne of Frederick the Great

Berger Daniel Gottfried "Frederick II flees after losing the Battle of Kunersdorf"

For this battle, Rumyantsev was awarded the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky. After Kunersdorf, Frederick is said to have told his generals:

In the autumn of 1760, Russian-Austrian troops of generals Chernyshev and Lassi (the son of a Russian field marshal) briefly entered Berlin.

Austrian General Franz Moritz Lassi, son of Russian Field Marshal Peter Lassi in a portrait by an unknown artist

Russian general Zakhar Chernyshev in the portrait of A. Roslin

This event is traditionally overrated in our country. The fact is that the goal of this campaign was not to capture the city, but to “demand a noble indemnity” - following the example of the Austrian general Gadik, who, at the head of a 14-strong detachment, carried out his “raid” on Berlin on October 16, 1757. These raids on Berlin in 1757 and 1760 had no strategic significance and had no influence on the course of the war.

1761 and Siege of Kolberg

Rumyantsev had to fight the Prussians once again in August 1761. The 18-strong corps he led approached Kolberg (Kołobrzeg) and immediately captured a fortified camp, which was defended by 12 soldiers of the Prince of Württemberg. At the same time, ships of the Baltic Sea approached the city. fleet. The siege of Kolberg lasted 4 months; on December 5 (16), the city capitulated. 3 thousand enemy soldiers and officers were captured, 20 banners and 173 artillery pieces became trophies.

A. E. Kotzebue. "The capture of Kohlberg"

It was then, during the assault on the enemy camp, that Rumyantsev for the first time in military stories struck in battalion columns. This blow would later be repeated near Turtukai by Suvorov, who, as we said in the first article, called himself a student of Rumyantsev. Alexander Vasilyevich will use this technique many times, which will be called “column - loose formation”. In front, “scattered,” was the light infantry, behind it were several infantry columns, between which there was regimental artillery, and behind was the cavalry, whose task was to strike one of the enemy flanks.

Tragic events in St. Petersburg and the resignation of Pyotr Rumyantsev

On December 25, 1761 (January 5, 1762), that is, 20 days after Rumyantsev captured Kolberg, the Russian Empress Elizabeth died. Her nephew, Peter III, who always opposed the war with Prussia, took the throne. Academician J. Shtelin recalled:

In this case, Peter III turned out to be simply a prophet. It was France that acted as an ally of the rebels of the Bar Confederation in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire during its new war with Russia - the same one that would glorify Pyotr Rumyantsev and Alexei Orlov, and in which Alexander Suvorov would win his first high-profile victories. It will be the French who will then push the Turks to a new war, finance them, assist in the reorganization and retraining of the Ottoman army, and modernization of artillery. And to provide assistance to the adventuress who went down in history as “Princess Tarakanova” - in Ragusa she will live in the house of the French consul.

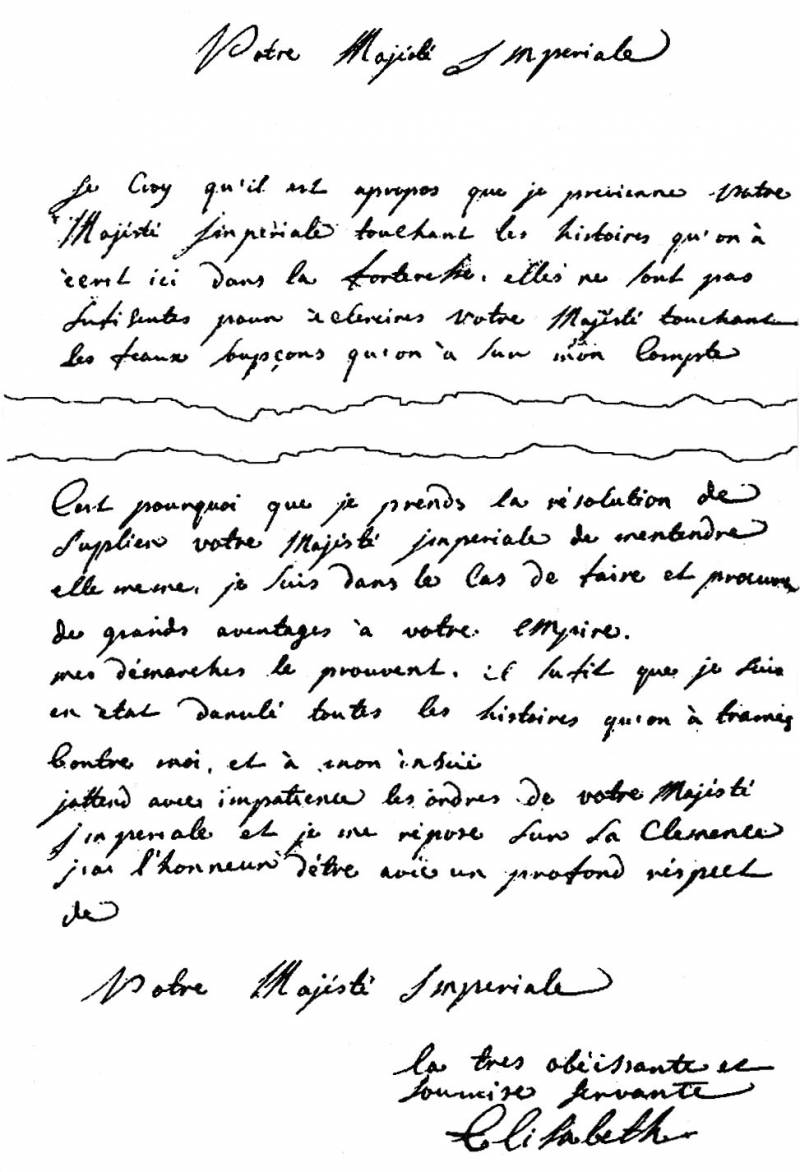

One of False Elizabeth's letters to Catherine II

By the way, the new king of France, Louis XVI, assessing the results of the Seven Years' War, later said:

But let's not get ahead.

The short reign of Peter III has long been told according to a hackneyed and completely false scheme. Briefly, the situation after Elizabeth's death is as follows. The feeble-minded and always drunk Peter III, who worshiped Frederick the Great, betrayed Russian interests, returned East Prussia and Königsberg to him without any conditions, but was about to start a war with Denmark for the unnecessary Schleswig and Dithmarschen. This caused outrage among the patriotic guards of St. Petersburg, who overthrew this pathetic emperor.

And what really happened?

В previous article we have already said that our country had no reasons and no reasons for war with Prussia, a state that did not have common borders with the Russian Empire. And there were no clear goals and objectives that could be solved in the event of victory over Prussia. In the Seven Years' War, Russia played the role of the cat from La Fontaine's fable, which burned its paws while pulling hot chestnuts from the fire for the cunning monkey. During this war for foreign interests, Russia suffered heavy demographic losses and found itself on the verge of financial collapse. Things got to the point where St. Petersburg officials had not been paid their salaries for years. Not surprisingly, the war was extremely unpopular in Russian society. And the “patriotically minded” guardsmen did not want to fight with anyone for a long time and categorically did not want to leave the capital’s cheerful taverns and cozy brothels. This was not the same Peter’s guard that heroically fought in the battles of the Northern War, but completely disintegrated “Janissaries”, ready at any moment to “turn the pot,” that is, to rebel against the legitimate government. This was known and understood by everyone; the French diplomat Favier, for example, wrote about them like this:

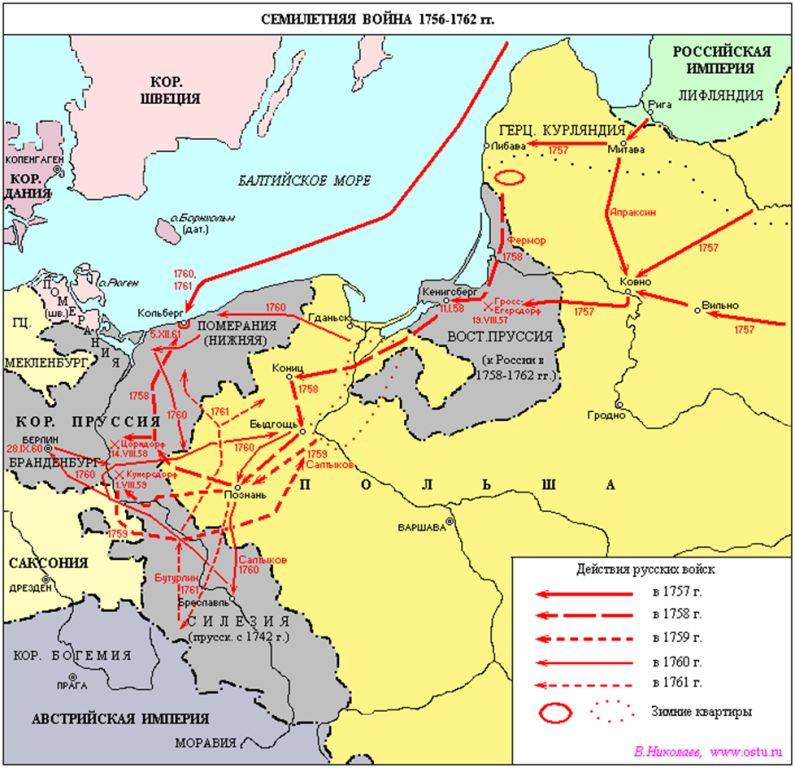

Russia's conquest of East Prussia would not be recognized by any European state. Official annexation would lead to a war like the Crimean one. And it was absolutely impossible to hold this province, cut off from Russian lands by the territories of the Duchy of Courland and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The land route to East Prussia could be blocked at any moment; supplies by sea depended on the position of Britain and Sweden. Look at the map again:

In this situation, the actions of Peter III were very reasonable and the only possible ones. The exit from the unnecessary war with Prussia made everyone extremely happy and was welcomed by all layers of Russian society. Let us remember that, having seized power, Catherine II did not even think about continuing this war - and this despite the fact that Russian troops were still in East Prussia and Königsberg. It was she, and not Peter III, who gave the order for their withdrawal - although she had every opportunity to fight with Frederick further.

But why, after the conclusion of peace with Prussia, did Russian troops continue to remain on the indigenous territory of Frederick the Great? The fact is that Peter III concluded an extremely profitable agreement with the Prussian king, according to which East Prussia would return only after the establishment of Russian power over Schleswig and Dithmarschen, which legally belonged to Peter III as the Duke of Holstein and Stormarn, but were occupied by Denmark. And these lands were not the St. Petersburg “window to Europe” and not the “bear corner” of agrarian East Prussia, but “elite real estate” in the then “European Union”, and even with a unique geographical position, allowing control of both the North and Baltic seas. Look at the map:

A powerful naval base in this duchy turned Russia into the mistress of Northern Europe.

To restore control over Schleswig and Dithmarschen, Frederick II pledged to provide 15 thousand infantry and 5000 cavalry to help Russia. The Russian army was to be led by the brilliant young commander Pyotr Rumyantsev, who was only 36 years old at the time. The Emperor awarded him the rank of General-in-Chief and awarded him the Orders of St. Andrew the First-Called and St. Anne. Rumyantsev's corps was still located in the area of \u12b\u4bKolberg and Stettin, and its numbers increased significantly: it now included 23 cuirassiers, 11 hussars, 59 infantry and 908 Cossack regiments - a total of 1762 people. Negotiations with Denmark were scheduled for July XNUMX. If they were unsuccessful, Russia and Prussia began joint military operations, and the Danes did not have the slightest chance of success. But even after this, Peter III retained the right to stop the withdrawal of Russian troops from Prussia “in view of the ongoing unrest in Europe" That is, the “Western Group of Forces” could remain in East Prussia for a long time, guaranteeing the “obedience” of Frederick the Great. Which, by the way, also took upon itself the obligation to support candidates convenient for Russia for the thrones of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the still independent Courland.

Contrary to historical myths, Peter III was very popular in Russia. After the publication of the famous “Decree on the Liberty of the Nobility”, they were even going to erect a golden monument to him. And the peasants expected exactly the same decree, which would free them from serfdom - and they had reason for such hopes. Peter III actually issued a decree limiting the personal dependence of peasants on landowners, which was immediately canceled by Catherine II. In total, during his short reign, this emperor prepared and published 192 laws and decrees - more than 30 per month. By the way, Catherine II signed an average of 12 decrees per month, Peter I - 8. Decrees were issued on freedom of religion, prohibiting church supervision over the personal lives of parishioners, transparency of legal proceedings and free travel abroad. By order of Peter III, a state bank was founded, into whose accounts he deposited 5 million rubles of personal funds - they were used to ensure the replacement of damaged coins and the first bank notes in Russia. The price of salt was reduced, peasants were allowed to trade in cities without obtaining permission or paperwork, which immediately stopped numerous abuses and extortions. It was forbidden to punish soldiers with batogs, and sailors with “cats” (lashes with four tails and knots at the ends). Catherine canceled the decrees of Peter III on "silverlessness of service", which prohibited rewarding officials "peasant souls"and state land - only orders, about ending the persecution of Old Believers, about the optional observance of religious fasts. Instead of the terrible “Secret Chancellery” abolished by Peter III, Catherine II ordered the organization of a “Secret Expedition”.

Peter III managed to free some of the monastery serfs, giving them arable land for eternal use, for which they had to pay a monetary rent to the state treasury. "For innocent patience with the torture of street people“He ordered the landowner Zotova to be tonsured into the monastery, and her property to be confiscated to pay compensation to the victims. A Voronezh landowner, retired lieutenant V. Nesterov, was forever exiled to Nerchinsk for driving a servant to death.

A well-known but not advertised fact: Catherine and her accomplices deceived the soldiers of the St. Petersburg garrison, informing them about the death of the emperor, and even staged a funeral procession. To stop the rebellion, Peter III only needed to appear in St. Petersburg - as Minich advised him. Or, without wasting time, move to Kronstadt in a timely manner, where you can simply wait one week. Contemporaries wrote about serious unrest in St. Petersburg, which occurred shortly after the seizure of power by Catherine II. The sobered up soldiers of many regiments realized that they had been deceived, and for some time the ground literally burned under the feet of the conspirators. The French ambassador Laurent Beranger reported to Paris on August 10, 1762:

(But the Preobrazhensky people, as you know, were late).

And on the same day, August 10, the Prussian Ambassador B. Goltz writes to Berlin:

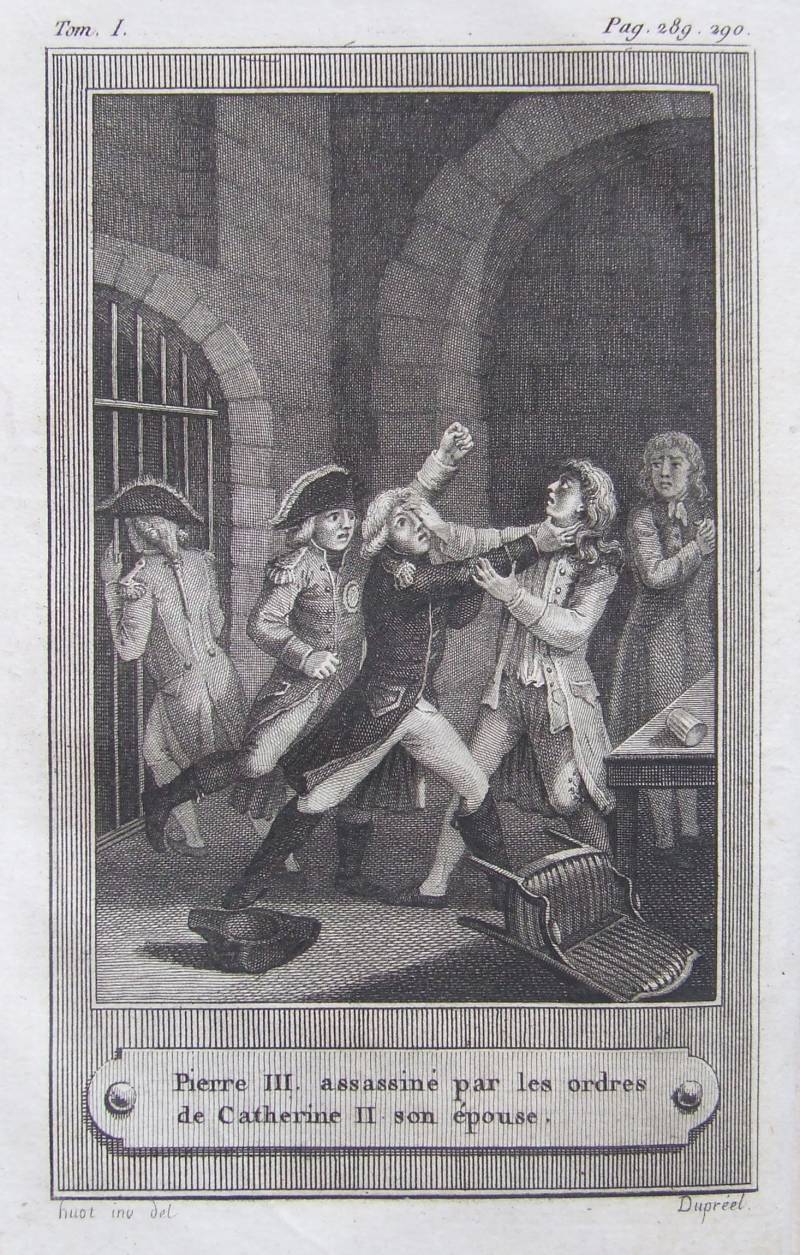

Finally, Peter III could freely get to Revel, board any ship and go to East Prussia - to Rumyantsev, who was unconditionally loyal to him. And soon he would receive a letter from St. Petersburg with the news that Catherine and her accomplices were impatiently waiting for him in the casemates of the Peter and Paul Fortress or Shlisselburg. He could have accelerated events by moving Rumyantsev’s army to St. Petersburg: the capital’s guards would have met real soldiers - veterans of the battles with the armies of Frederick the Great, on their knees. However, Peter III, as is known, abandoned the fight and was killed in Ropsha.

Frontispiece from the book “History of Peter III” by Jean Charles Thibault de Laveau, 1799 edition.

Having received the Manifesto on the accession to the throne of Catherine II, Rumyantsev for a long time refused to take the oath to the Empress, as he wanted to be convinced of the truth of the information about the death of Peter III, and then submitted his resignation, transferring command to Count P. I. Panin. Fortunately for our country, he soon returned to military service. Ahead was another Russian-Turkish war, victories in which would immortalize his name. We will talk about this in the next article.

Information