“Indigenization” and “the fight against Great Russian chauvinism”: national policy in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and its results

During the Civil War in Russia, the Bolsheviks sought to attract the sympathy of small nations, promising the creation or recognition of national-territorial regions and republics and granting their people the broadest rights in matters of self-government and national culture. This subsequently resulted in the policy of “indigenization”, which was carried out in the 1920s by the Soviet government in ethnic regions by replacing Russian with national languages.

The goal of the “indigenization” policy was to increase the trust of ethnic minorities in Soviet power, through encouraging local residents to actively participate in government. It was based, on the one hand, on the encouragement of the cultural and political development of national minorities, and on the other hand, on the implementation of measures aimed at reducing the status of the Russian people, namely, transforming them from a state-forming people into one of the peoples inhabiting the territory of the Soviet state [1 ].

This policy most often led to the infringement of the rights and interests of the Russian people. In most cases, the Bolsheviks, in the course of implementing their national policy, gave preference to peoples and ethnic groups that were politically loyal to them, providing them with the maximum possible preferences, often at the expense of other ethnic groups. This aspect of Bolshevik national policy was especially vividly embodied in the North Caucasus, where the Bolsheviks continued to speculate on numerous ethnic contradictions between the Cossack and mountain populations [2].

It got to the point that in 1930, within the framework of the First All-Union Conference of Marxist Historians, the main ideologist of the Soviet historical science, academician M. N. Pokrovsky stated in relation to Russian history:

Further specifying my theses within the framework of the article “The Emergence of the Moscow State and the Great Russian Nationality”:

This echoes a similar scandalous statement by contemporary journalist and politician Sergei Karnaukhov, who last week said that Russia should abandon Russianness, citing the eccentric philosopher Vladimir Solovyov, by the way, one of the first globalists.

- said Karnaukhov.

The national policy of Soviet Russia in the 1920s adhered to precisely this principle - a ban on Russian nationalism and support for the nationalisms of small nations.

The Bolsheviks’ struggle against “Great Russian chauvinism”

In the Bolsheviks' understanding, nationalism was

Supporting the self-determination of peoples was for them a means necessary at the first stage of the socialist revolution in order to reduce the mistrust and hostility of workers and peasants of different nationalities towards each other.

If the White movement proceeded from the maxim of “One and indivisible Russia” and the Russian language as the only state language, then the Bolsheviks already at the VII All-Russian Conference of the RSDLP outlined their position, which boiled down to recognizing the right of the nation [i.e. e. national minorities] to secede and create their own state - if it wants this, or if a national minority wants to remain part of Russia, it is given the right to create regional autonomy [1].

In 1922, Vladimir Lenin wrote:

That is, Lenin made it clear that Russians should not only observe the principle of equality of nations, but also create inequality that could “make amends” for the Russians to supposedly “oppressed” minorities. Such politics have in common with modern left-liberalism, where there are “historically oppressed groups” whose oppression is based on discrimination due to perceived or real differences. Oppression in liberalism "imposed by majority groups on minority groups».

Prominent revolutionary Nikolai Bukharin spoke in the same vein:

As modern researchers rightly note, the course towards the development of ethnocultural diversity pursued in the 1920s was accompanied by a tough struggle against the natural dominant position of Russians in the country. V.I. Lenin, using the formula of the French writer Marquis Astolphe de Custine “Russia is a prison of nations” (“This empire, for all its immensity, is nothing more than a prison”) [6, p. 225], focused exclusively on the oppressed position of the non-Russian peoples of the Russian Empire [5].

Party documents of that time repeatedly stated that “Great Russian chauvinism” was an enemy for the Soviet Union more dangerous than any form of local nationalism. Even traditional Russian culture was condemned as "oppressor culture».

In an economic sense, this policy found expression in the following: on August 21, 1923, the Union Republican Subsidy Fund of the USSR was created, funds from which were intended for the economic and social development of the Caucasian, Central Asian and other union republics, including Ukraine. The fund was formed at the expense of the RSFSR, but the latter did not receive anything from it [5].

Much later, Harvard University professor Terry Martin would call this policy “positive discrimination policy“, thereby showing that it was not the Americans in the 1970s who were the first to turn to its implementation within the framework of the policy of multiculturalism, but the Bolsheviks 50 years earlier, and they carried it out in a much more radical form.

Policy of "indigenization"

Based on the postulate of the Russian Empire as a “prison of nations,” the Bolshevik leadership set a course for the so-called “indigenization.” According to this concept, the former “oppressed peoples” received all kinds of benefits and privileges, some of which were mentioned above.

Indigenization implied not only the involvement of representatives of the autochthonous population in government bodies, but also the translation of all office work into local languages.

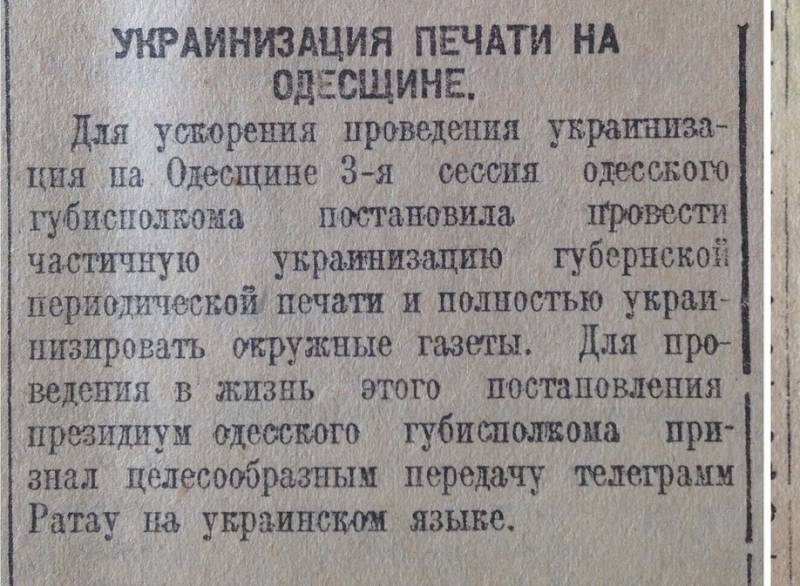

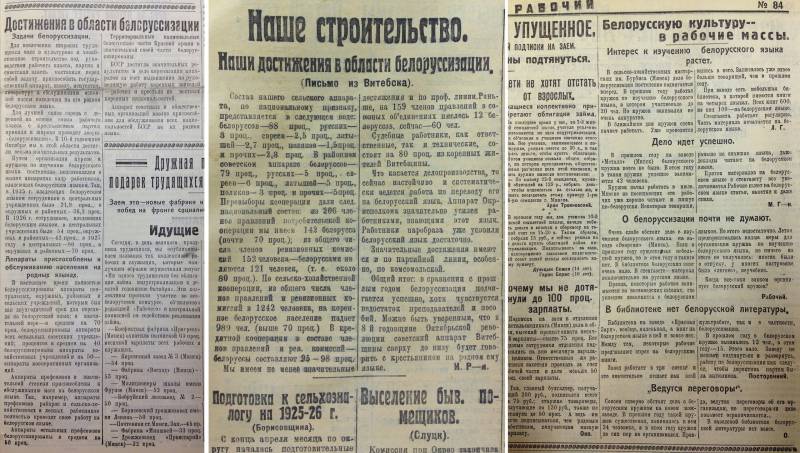

As a result of this policy, in Ukraine, for example, by 1930 there were only three large Russian-language newspapers left, and in Odessa by the end of the 1920s. All schools were Ukrainized (despite the fact that the number of Ukrainian students here was only 1/3 of the total) [8].

Ukrainian communists advocated the annexation of vast areas with a predominant Ukrainian population to the Ukrainian SSR and/or the development of Ukrainian national culture in them. Their sphere of interests included Kuban and some other regions of the RSFSR. By May 1928, a compromise was reached: Kuban and other regions decided to remain part of the RSFSR, but to carry out full-scale Ukrainization on its territory.

Those who disagreed with the Ukrainization plan were subjected to repression. Thus, in July 1930, the Presidium of the Stalin District Executive Committee decided

In Leningrad in the early 1930s. Newspapers were published in 40 languages, including Chinese, and radio broadcasts were conducted in Finnish (although only 130 thousand Finns lived in the Leningrad region at that time). In the North Caucasus, “indigenization” also affected the Russian population, primarily the Cossacks, who in significant numbers were evicted from the plain villages inhabited by Chechens, Ingush, and the peoples of Dagestan for their “counter-revolutionism” [8].

How did the population perceive the processes of “indigenization”?

Population's reaction to the policy of “indigenization”

The events of 1927, namely the so-called “war alarm” of 1927, showed the ambiguity of the policy of “indigenization” in the face of the growing danger of a military conflict. An analysis of public sentiment carried out by state security agencies showed that

It is noteworthy that negative sentiments regarding the coming war and, as a consequence, the need to defend the socialist Fatherland, were expressed precisely by the original Russian regions. And this is not surprising: the costs of indigenization, the essence of which actually amounted to a violation of the rights of Russians not only in the union republics, but also in the autonomous republics of the RSFSR, were hardly a secret for both the workers and peasants of the Russian regions of the country. Thus, in the Mountain Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic the Russian population complained:

In Kalmykia it also asked:

In the Saratov region, in places where the policy of indigenization was implemented in favor of the German-speaking population, unrest on ethnic grounds was observed between the Russian majority and the German minority, the reason for which was the reluctance of Russians to educate their children in German [10].

In the villages of the Byelorussian SSR directly bordering the RSFSR, they asked to leave Russian as the language of instruction in schools. Regarding Belarusization, the following story of the Belarusian teacher G.P. Stsepuro, published in the collection “The Central Committee of the RCP(b)-VKP(b) and the National Question” is noteworthy:

Such phantasmagoric cases were far from isolated.

Suspension of the “indigenization” policy in the second half of the 1930s

In the 1930s, there was a gradual turn from the policy of “indigenization” to the policy of Soviet patriotism, based on increasing the status of the Russian people. The strategy of “internationalization” was popular among the Bolsheviks as long as hopes for a world revolution remained. After the course was taken to build socialism in a single country, this model became less relevant.

Already in 1931, Joseph Stalin wrote a letter to the editor of the magazine “Proletarian Revolution”, in which he pointed out the presence of fundamental historical errors in the works of official Bolshevik historians who neglected the real practice of Bolshevism [1].

The intensive indigenization of personnel in the union and autonomous republics that took place over the course of a decade led to the strengthening of elites among local communists who wanted the immediate transition of their ethnic groups to the construction of their own nations, without any equivocation towards communism. Therefore, the Bolsheviks begin an attack on chauvinism towards Russians on the part of national minorities.

In addition, in the second half of the 1930s, rehabilitation was carried out as personalities who made a significant contribution to the development of Russian science and culture (the most notable example is giving A. S. Pushkin the status of “great Russian national project"), and a number of statesmen of Tsarist Russia.

However, despite the fact that mass “indigenization” was stopped, mass Russification never began. I. Stalin sharply slowed down “indigenization,” which had already begun to represent a potential ground for separatism, but did not stop it completely, and it, although not at such a fast pace, continued to be carried out, which led in the 1970s to the final consolidation of the power of local elites in the allied republics [5].

According to the data of the All-Union Population Census of 1939, the trends of “indigenization” of the Soviet nomenclature continued. According to the census, in 10 union republics (without the RSFSR) in 1939 there were 619,2 thousand executive employees, of which 346,9 thousand, or 56%, belonged to persons of the titular nationalities of these republics. For example, in Ukraine, among all management personnel, Ukrainians made up 59,6%, in Armenia, Armenians - 86,2%, in Georgia, Georgians - 67,1%, in Uzbekistan, Uzbeks - 51,9%.

It can be stated that the change in the status of the Russian people towards its improvement never fully occurred. This is probably due to the fact that the concept of “Soviet people”, based on those laid down in the 1930s. ideas about the role of the Russian people as “elder brother” and “first among equals” was never accepted as the main identification matrix by the peoples of the USSR, which ultimately led to an aggravation, among other reasons, in the late 1980s and early 1990s. x years national contradictions, ethnic conflicts and the collapse of the country [1].

Today's Russian Federation largely continues Soviet national policies. For example, in the formula “multinational people of the Russian Federation”, included in the Preamble of the 1993 Constitution, echoes of the slogan about the “multinational Soviet people” are clearly heard. The practice of “positive discrimination” in national republics also continues, as does flirting with local nationalists. These processes continue by inertia due to the lack of their own clearly formed national policy.

Использованная литература:

[1]. Arshin K.V. Stopping the policy of “indigenization” in the USSR (historiosophical aspect). // Abyss (Questions of philosophy, political science and social anthropology) 2023. No. 1(23). pp. 124-131.

[2]. Solovov E.M. Interethnic interaction and national policy of the Bolsheviks during the civil war. [Electronic resource] URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/mezhetnicheskoe-vzaimodeystvie-i-natsionalnaya-politika-bolshevikov-v-gody-grazhdanskoy-voyny-1917-1920-gg

[3]. Kuznechevsky V.D. Stalin and the “Russian question” in the political history of the Soviet Union. 1931-1953, M.: Tsentrpoligraf, 2016.

[4]. Letter from V.I. Lenin “On the question of nationalities or “autonomization””. December 30-31, 1922 // V.I. Lenin. Full collection cit., vol. 45, pp. 356-362.

[5]. Achkasov V. A. “National revolution” of the Bolsheviks and “national policy” of modern Russia // Bulletin of St. Petersburg University. Political science. International relationships. 2018. T. 11. Issue. 1. pp. 3-14.

[6]. Custine A. de. Russia in 1839 / Transl. from fr. O. Grinberg, S. Zenkina, V. Milchina, I. Staff. – St. Petersburg: Kriga, 2008.

[7]. Twelfth Congress of the RCP(b). April 17-25, 1923. Verbatim report. M., 1968. P. 613.

[8]. Markedonov S. Turbulent Eurasia: interethnic, civil conflicts, xenophobia in the newly independent states of the post-Soviet space. – M.: Moscow Bureau for Human Rights, Academia, 2010.

[9]. Mozgovoy V.I. Ukrainian legislation in the field of national language policy and the reality of social processes (1917-2021) // Neophilology. 2022. T. 8, No. 2. P. 228-242. https://doi.org/10.20310/2587-6953-2022-8-2-228-242.

[10]. German A.A. The policy of “Indigenization” in the autonomous republics of the RSFSR in the 1920s (based on the materials of the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of the Volga Germans) // Izv. Sarat. University of Nov. ser. Ser. Story. International relationships. 2013. No. 4. pp. 94-97.

[eleven]. Central Committee of the RCP (b) - CPSU (b) and the national question. Book 11: 1-1918 – 1933 (SUE IPK Ulyan. Printing House).

Information