From second lieutenant to marshal: the military career of the “Duke of Victory” Armando Diaz

On May 23, 1915, Italy entered World War I on the side of the Entente, declaring war on Austria-Hungary. It cannot be said that this decision was easy for the country - the political leadership hesitated for a long time, since there were three influential groups in the country: “Germanophiles”, “interventionists” and “neutralists”. For example, Foreign Minister San Giuliano, taking into account all the negative consequences of the war, was inclined to the point of view of the “neutralists” [4]. In addition, the possibility of war with Germany frightened many generals.

There were reasons for fears, since the condition of the Italian army left much to be desired - researchers note that the Austrian armed forces were superior to the Italians in weapons and combat training of personnel; the situation in the Italian army was especially bad with the training of middle and senior command officers. In addition, the army was greatly weakened by the war with Turkey (1911-1912).

The topic of Italy's participation in the First World War is rather poorly covered in domestic historiography - while some information can still be found about the Battle of Caporetto and the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, there is very little information about the Italian generals and military planning. Historians have also ignored the general who received the title of Duke of Victory after the end of the First World War, and later the title of Marshal of Italy, Armando Diaz. In Italy, Diaz is considered the main hero of the First World War. In general, Italian historiography highly appreciates his contribution to the Supreme Command.

There are no works in Russian that would examine in detail the military career of Armando Diaz, highlighting his contribution to the victory at Vittorio Veneto and the reform of the Italian army in the 1920s. Apart from a brief biographical note by historian Konstantin Zalessky, in the book “Who Was Who in the First World War” there is nothing more about Diaz historical works.

For this reason, when writing this material, the author mainly used Italian-language sources - primarily the article by military historian Giorgio Rocha, dedicated to A. Diaz in volume 39 of the “Biographical Dictionary of Italians” (Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani), and the book of this historian L'esercito italiano da Vittorio Veneto a Mussolini, 1919-1925 (The Italian Army from Vittorio Veneto to Mussolini, 1919-1925).

Military career of Armando Diaz before World War I

Armando Vittorio Diaz was born in Naples on December 5, 1861, into a family of Spanish origin. Armando's grandfather was a military officer during the reign of Ferdinand II, and his father was an officer in the Italian Naval Engineering Corps fleet; the mother of the future marshal came from a family of magistrates. Diaz's father, who worked in the arsenals of Genoa and Venice, died in 1871, after which the widow and four children returned to Naples, supported by the tutelage of her brother Luigi.[1]

Diaz began his military career early - after passing the entrance exams to the Turin Military Academy, he entered service there and already in 1879 received the rank of second lieutenant of artillery. In 1884 he was promoted to lieutenant and transferred to the 10th Field Artillery Regiment stationed at Caserta. He remained there until March 1890, when he was promoted to captain and transferred to the 1st Field Artillery Regiment stationed at Foligno.

Later, Armando Diaz passed the entrance exams to the Military School, which he attended in 1893-1895, demonstrating excellent results and taking first place in the final ranking of his course. His military career did not become an obstacle to establishing his personal life - during the same period, in 1895, he married a girl from a Neapolitan family of lawyers, Sarah de Rosa. This marriage turned out to be strong and happy, as evidenced by the three children who appeared in the family within a few years [1].

From 1895 to 1916, Diaz's career was spent primarily in the offices of the Headquarters Corps command, where he worked for a total of about sixteen years, leaving Rome for only eighteen months to command a battalion of the 26th Infantry Regiment, after being promoted to major in September 1899. .and for just over three years in 1909-1912.

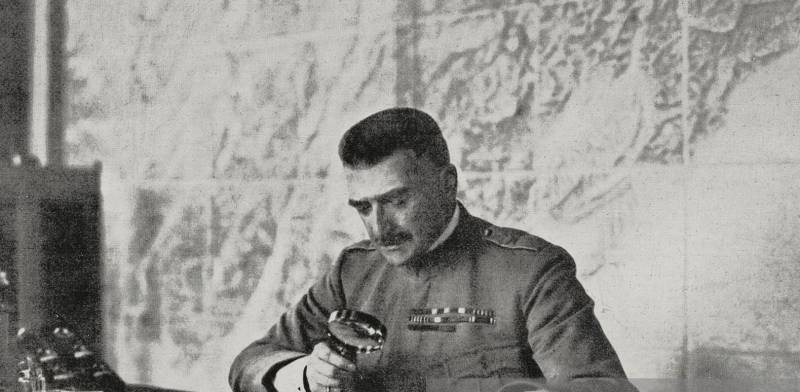

In Rome he served mainly in the secretariat of the army chief of staff T. Saletta and then A. Pollio: a position that involved daily confrontation with the reality of the army (staff, budgets, weapons) and the Roman political world. He proved himself to be a tireless worker, capable of making dependent services work at full capacity, but at the same time friendly and diplomatic. A. Diaz did not advertise his political interests, but was well informed about what was happening in parliament and in the country and knew how to juggle politicians and foreign military attaches [1].

Historian Giorgio Rocha describes Diaz as follows: of medium height, stocky but not overweight, with short hair and a large mustache, elegant but at the same time not striving for ostentation, taciturn and polished, well versed in French, authoritative but not authoritarian, demanding, but understanding. Armando Diaz was an officer who worked hard and well and had inner strength [1].

With the rank of lieutenant colonel, he left Rome in October 1909 in connection with his appointment as chief of staff of the Florence division. On July 1, 1910, he was promoted to colonel and took command of the 21st Infantry Regiment stationed in La Spezia, where he managed to win the favor of the soldiers by maintaining a strict disciplinary regime and taking an active interest in their living conditions.[1]

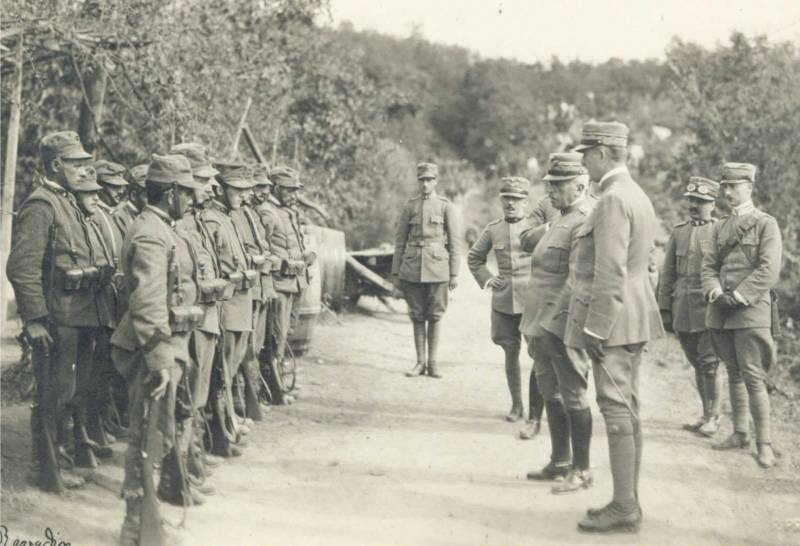

In May 1912, he was sent to Libya to relieve the ill commander of the 93rd Infantry Regiment. There, as researchers note, he showed feelings of affection and trust that were rare for the army of that time towards his new soldiers.

Diaz paid a lot of attention to the soldiers, personally monitored the observance of shifts between the trenches and rest, the provision of leaves, and ensuring that everything possible was done to ensure adequate and regular nutrition, so that the troops in the rear had a certain comfort. He never missed an opportunity to talk to the soldiers during his frequent inspections of the trenches and to encourage them with a few kind words. From Libya he wrote that "the whole secret is in the human factor", and said:

On September 20, 1912, at the Battle of Sidi Bilal near Zanzur, while leading troops in an attack, he was wounded by a rifle shot in the left shoulder. Before leaving the battlefield, he wished success to his regiment and kissed the banner. For his participation in the military campaign in Libya, he received the officer's cross of the Military Order of Savoy [1].

In October 1914, Díaz was promoted to major general and assigned to command the Siena Brigade, but was immediately recalled to army headquarters as attache general. At the moment when Italy entered the First World War and the Supreme Command of the Mobilized Army was created, in which he was the highest officer after Cadorna and his deputy C. Pollio, Diaz was put in charge of operations, but despite the name, he was not involved in planning operations (troop control was centralized in the hands of Cadorna and his small secretariat). Nevertheless, he led all the departments and services of the High Command and, therefore, had a general understanding of the situation in the army [1].

The Italian Army in World War I before the defeat at Caporetto

Italy entered the Great War primarily thanks to the active steps taken by the head of the cabinet, Antonio Salandra, and the head of the Italian Foreign Ministry, Sidney Sonnino. First, Salandra declared neutrality, refusing to enter the war on the side of the Central Powers (which Sonnino initially advocated), and then began to conduct secret negotiations with London about the possible entry into the war on the side of the Entente.

Giovanni Giolitti, who headed the “neutralist” camp and had serious influence in parliament, actively contributed to the fact that the majority of parliament opposed the declaration of war. He believed that Italy was not prepared militarily and took steps to overthrow Salandra's cabinet. Public sentiment, meanwhile, leaned more towards Italian participation in the war, as evidenced by the massive May demonstrations known as Radiosomaggismo.

The last word in this conflict remained with King Victor Emmanuel III, who rejected Salandra's resignation, and on May 23 Italy entered the war. The first difficulties began to appear a few months after the country entered the war. In particular, as historians note, the conduct of the war manifested itself as a discrepancy between the political plan and military leadership (the Chief of the General Staff corresponds with the government through the Minister of War, who, however, is not informed of his steps by Prime Minister Salandra; the plan of operations is reported by Cadorna to the king, but not the government), and friction between the government and the High Command [3].

Luigi Cadorna, head of the General Staff and de facto commander of the army since July 1914, demanded immediate general mobilization immediately after Italy declared neutrality. The Cadorna-Zupelli program, implemented from October 1914 to May 1915, provided for the creation of new divisions in Libya and Albania, the improvement of equipment and weapons, the expansion of the siege fleet, and the appointment of new officers with accelerated courses [5].

Historians Irene Guerrini and Marco Pluviano note that as a military leader, Cadorna believed that the Italians were pathologically undisciplined as a society long corroded by subversive anti-militarist propaganda, while for him discipline in the army seemed more important to victory than the necessary military equipment [6].

Historian Giorgio Rocha, in turn, does not highly appreciate Cadorna’s leadership qualities - the elderly general did not understand new methods of warfare, his troops were trained only in a frontal attack in compact masses, unable to outflank the enemy. Senior officers were promoted mainly for how energetically they were able to throw exhausted troops into frontal assaults [5].

Cadorna had too strict ideas about the soldier and his discipline, as a result of which he did not pay due attention to the material and moral well-being of the troops - rest, ensuring normal nutrition, promoting the goals of the war, helping families, etc. At the same time, in every sign of fatigue and discontent, he suspected subversive and defeatist tendencies [5].

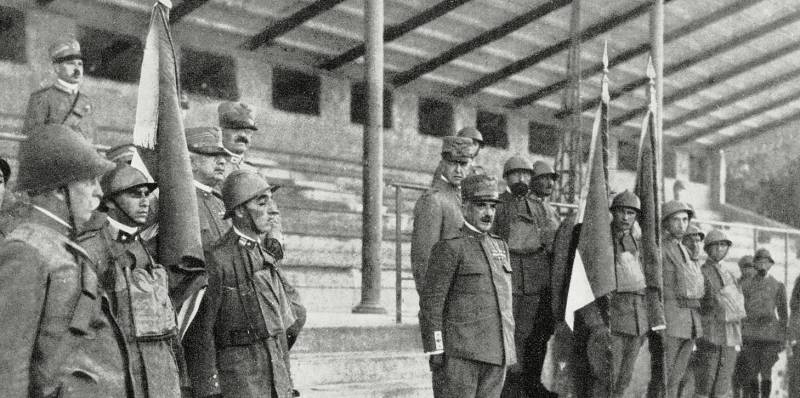

At the end of October 1917, when a new government was formed in Italy, Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando, King Victor Emmanuel III and Minister of War General Vittorio Alfieri agreed on the need to replace Cadorna. It was decided to make Armando Diaz his successor, but the appointment was postponed until the front stabilized. However, after the defeat of the Italian army at the Battle of Caporetto, the king took the initiative to immediately place Diaz at the head of the army, appointing Gaetano Giardino and Pietro Badoglio as his deputies.

General Diaz learned of his high appointment, which was completely unexpected for him, on the day of November 8. He went to the High Command, telling Lieutenant Paoletti:

Armando Diaz as Chief of the General Staff and his contribution to the victory at Vittorio Veneto

Giorgio Rocha notes that assessing the work of Armando Diaz as commander-in-chief of the Italian army in the last year of the war is not easy, since, firstly, Diaz and his immediate subordinates did not leave any written evidence about this period, and secondly, during the reign of the Fascist Party, the name Diaz was often used for propaganda purposes (the fascists portrayed him as the undisputed hero of the Great War), thirdly, historians focus their attention mainly on the Cadorna period.

His first achievement, without any doubt, was his ability to make the High Command function adequately to the needs and scale of the Great War. Cadorna concentrated too much power in his hands, which is why he could not control the details of his plans and the execution of orders, and did not understand the seriousness of the problems that befell the government [1].

Drawing on his many years of experience as a staff officer and a more open view of the needs of the conflict, Díaz reorganized the High Command, strengthening the role of his deputy P. Badoglio and the responsible general S. Scipioni, reorganizing the work of the branches and giving each of them specific and specific responsibilities.

The new High Command paid special attention to the development of intelligence services and strengthening the role of liaison officers, who were supposed to provide direct information on the situation on various fronts, without, however, bypassing the army commands, with which very close relations were maintained [1].

Particularly successful was the collaboration with Badoglio (Díaz elegantly got rid of another deputy commander-in-chief, Giardino, by promoting him), who was mainly involved in operations and coordination between the departments of the Supreme High Command, freeing Díaz from much of the routine work and winning his full confidence [1 ].

Diaz always refused to launch offensive operations that had no other purpose than to indirectly relieve the French front. The command of the allied armies (in particular, General F. Foch) constantly demanded that Italy intensify offensive actions, but the general categorically rejected the possibility of going on the offensive in the first half of 1918 [7].

The undeniable merit of Armando Diaz was also his active interest in the living conditions of soldiers. The general did everything possible to provide the soldiers with regular and high-quality food even in the trenches, guarantee them vacations and rest, and ensure a more careful attitude towards their life and health. The results were not the same everywhere, but they were noticeable among the troops and were welcomed [1].

After Caporetto, the strategic position of the Italian army had become much more vulnerable (there was no room for further retreat, especially since many feared a possible internal reaction), the reserves of men on which Cadorna could draw with relative breadth were now meager. Nevertheless, Diaz was able to use the resources available to him quite effectively.

Historians evaluate Diaz's work as commander-in-chief, of course, positively. His prudent and calm firmness, understanding of the horrors of war, sincere concern for the living conditions of the troops, respectful attitude towards subordinates, and finally, the ability to cooperate with political forces and create a popular image without demagogic techniques made him the right person in the right place at the final stage of a grueling war [1 ].

On October 24, 1918, Italian troops launched a general offensive. The actions of the troops on the Isonzo were called the battle of Vittorio Veneto. During weeks of fighting, Italian troops defeated the demoralized Austro-Hungarian troops. On October 29, the Austro-Hungarian command requested peace on any terms [7].

Diaz's career after the end of the Great War

After the end of the war, political differences between the “interventists” and “neutralists” intensified again, which led, among other things, to a tightening of disagreements within the Italian army. A significant part of the country suffered from the war and demanded an account from the political leadership - opponents of the war condemned both the interventionists and the army, making no difference between them. The crisis caused by the war prevented a calm discussion of post-war problems [2].

The violent controversy provoked between July and September by the publication of the investigation into the Caporetto case could not please Armando Diaz due to its nature of radical criticism and opposition to the war, but this criticism did not affect him personally, since the accusations were unilaterally directed against Cadorna and his leadership military actions [1].

One of the main issues on the agenda of the High Command was the demobilization and reform of the Italian army. At the time of the signing of the peace treaty, the Italian army numbered over 1 soldiers and about 600 thousand officers. Finance Minister Nitti spoke of the almost two billion a month that Italy spends on maintenance for the army and navy, which was extremely burdensome for the economy.

In order to save money, A. Diaz proposed, among other things, to reduce the contract period from 24 to 8 months, but with several conditions - proper training of recruits, the availability of suitable instructors, and refusal to use troops for police services [2].

Meanwhile, active political struggle was taking place in the leadership of the army. Based on the fact that information about the views of military leaders of that time is quite scarce and sometimes contradictory, which is due to the lack of serious biographical research. Historian Giorgio Rocha identifies two groups of generals in the Italian army, separated by personal rivalries and serious differences in political positions.

The first group was led by General Gaetano Giardino and also included the Duke of Aosta (Emmanuel Philibert) and Admiral Taon di Revel. Politically, this group was nationalist, especially sensitive to foreign policy issues, and advocated the most extensive territorial annexations and international power politics. Regarding the problems of the army, they were avid conservatives [2].

The other group was led by Armando Diaz and Pietro Badoglio, that is, the High Command. Both had no real political position or political ambitions, but had a lot of experience working with the government. They knew the bureaucratic apparatus well, were effective managers, but at the same time they were poor speakers and did not participate at all in the Senate meeting. Thus, they had some advantage over the Giardino group, because they were interested in the army, not politics. Diaz and Badoglio also enjoyed the support and trust of the king [2].

Armando Diaz welcomed the formation of the Nitti government with its normalization program, personally appointed a new Minister of War, General A. Albricci, and fully cooperated in matters of demobilization of the army. In November 1919, he resigned as Chief of Staff of the Army and took up the honorary position of Inspector General of the Army, which was abolished in April 1920.[1]

However, the illustrious general did not remain without a position for long - in February 1921, Badoglio transferred the powers of the chief of staff to the newly created collegial body, the Military Council, which included Armando Diaz. The War Council did not show good results, effectively blocking an attempt to restructure the army, but this did not affect Diaz's prestige - in the fall of 1921, in gratitude for his national role in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, he received the title of Duke of Victory [1].

He did not take an active part in the political struggle that unfolded in Italy in 1920-1922. During the growing political crisis associated with the March on Rome in October 1922, Luigi Facta cabled the king:

This meant that Diaz recommended a political solution to the crisis rather than reprisals against fascist units, which he also personally reported to the king. After the success of the March on Rome, Diaz agreed to join Mussolini's first government as Minister of War. Under Mussolini, he was primarily concerned with the reorganization of the army.

In early 1924, Díaz decided to resign from the government because he believed that the reorganization of the army was already completed, and because office work was becoming increasingly burdensome on his health (during the First World War he contracted chronic bronchitis, which gradually led to his death from emphysema). He left the War Department to General A. Di Giorgio, chosen with his consent.

After leaving the government, Díaz was appointed deputy chairman of the advisory committee of the High Defense Commission, a position with undefined tasks. On November 4, 1924, he received the rank of Marshal of Italy. Armando Diaz died in Rome on February 29, 1928.

References

[1]. Giorgio Rochat. Diaz, Armando Vittorio. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 39: Deodato-DiFalco. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1991.

[2]. Giorgio Rochat. L'esercito italiano da Vittorio Veneto a Mussolini 1919-1925, Laterza, Roma-Bari 2006.

[3]. Federico Lucarini, Salandra Antonio, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 89, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2017.

[4]. Chernikov Alexey Valerievich. Diplomatic and military cooperation between Italy and Russia during the First World War: 1914-1917: dissertation of a candidate of historical sciences: 07.00.03. – Kursk, 2000.

[5]. Giorgio Rochat, Cadorna Luigi, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 16, Roma, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1973.

[6]. Guerrini I., Pluviano M. Executed without trial. "Tommasi Memorial Note" on summary executions during the First World War. [Electronic resource] URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/2020-02-022-guerrini-i-pluviano-m-rasstrelyannye-bez-protsessa-memorialnaya-zapiska-tommazi-o-kaznyah-bez- suda-i-sledstviya-vo-vremya-pervoy

[7]. Zalessky K. A. Who was who in the First World War. – M.: ACT: Astrel, 2003.

Information