Russian empire. New facts

Previous article “Russian Empire. An Honest Look ”caused a mixed reaction. There is a lot of controversy and controversy. Unable to respond to every comment, the author decided to publish a new article containing additional facts to support the point of view expressed. The article examines the rates of economic growth of the Russian Empire before the First World War, the development of its industry, the growth of the welfare of citizens. A wide range of statistical material is provided, on the basis of which it is possible to draw quite unambiguous conclusions.

Growth rates

One of the main indicators of a country in all its eras is the rate of economic growth.

This is how Paul Gregory assesses the development of the economy of the Russian Empire:

And another quote from Paul Gregory:

As for the growth rate of the Russian Empire in comparison with the leading countries of the West, Paul Gregory gives the following figures.

Russia (1883-1887 - 1909-1913) - 3,25%.

Germany (1886-1895 - 1911-1913) - 2,9%.

USA (1880-1890 - 1910-1914) - 3,5%.

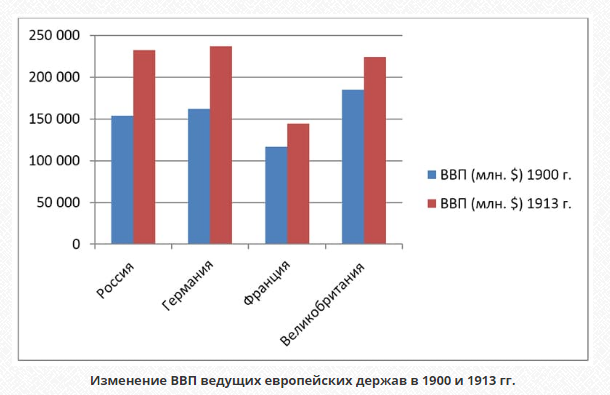

Additional information can be gleaned from the following graphs:

The graph clearly shows that among the leading countries in Europe, the Russian Empire ranked first in terms of economic growth. The graphs are based on Angus Maddison's calculations

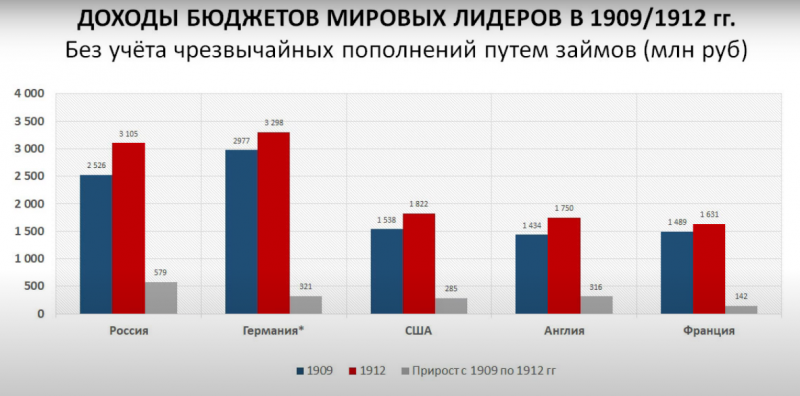

The revenues of the Russian budget are also very indicative, which before the First World War were second only to those of Germany, surpassing England and even the United States.

Economic and industrial development

In this article, it is appropriate to provide broader information about the economic and industrial development of the Russian Empire before the First World War.

For this we will use the information of the modern historian A. A. Borisyuk. He gives the following figures.

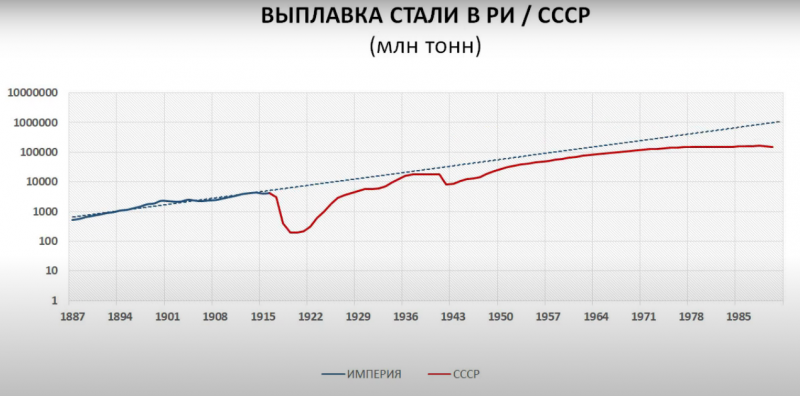

Steel smelting: 1892-1916 - an increase of 4,7 times, 1916-1940. - an increase of 4,3 times.

Iron smelting: 1892-1916 - an increase of 4,2 times, 1916-1940. - an increase of 3,9 times.

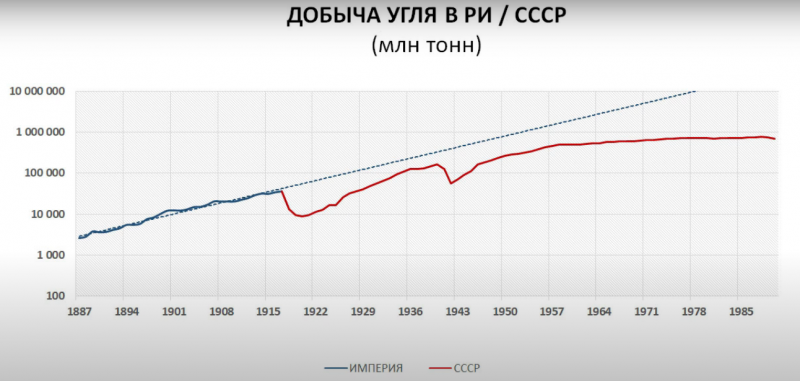

Coal mining: 1892-1916 - an increase of 8,5 times, 1916-1940. - an increase of 4,8 times.

Electricity generation: 1916 - 2,6 billion kWh, 1924 - 1,6 billion kWh.

Brick production: 1894–1913 - growth by 4 times, 1913-1940. - an increase of 2,2 times.

Glass production: 1894–1913 - growth by 4,5 times, 1913-1940. - growth by 1,9 times.

Cement production: 1894-1913 - 15 times growth, 1913-1940 - growth by 3 times.

Andrey Anatolyevich also gives some social indicators:

Change in the number of schools: 1894-1914 - 2 times growth, 1914-1928 - decline by 1,1 times.

Change in the number of students: 1894-1914 - growth by 3 times, 1914-1928. - growth by 1,2 times.

Change in the number of hospitals: 1903-1913 - growth by 1,5 times, 1914 - 1928 - decline by 1,5 times.

A. A. Borisyuk pays special attention to the program for the construction of railways. According to him, during the reign of Nicholas II, the greatest increase in the length of public railways for the entire history Russia. Thus, the increase in the length of railways in the period from 1894 to 1917 amounted to 46 thousand kilometers.

The graphs clearly indicate that never in the entire history of Russia have railways been built so intensively as during the reign of Nicholas II.

The construction of railways makes it possible to provide factories with more and more large-scale supplies of fuel and raw materials.

The main cargo of the empire's railways is coal. The supply of coal to enterprises was a key function of the railways. Railways are becoming the foundation of industrialization.

In Russia, the construction of railways is specific. It starts up more slowly than in Europe, but over time it reaches a higher pace. As long as the European industry has a transport advantage, it is in the lead. Their factories receive more competitive opportunities in the supply of fuel and raw materials, and, therefore, favorable conditions for development.

Despite the record resource potential, we cannot take full advantage of this potential due to transport restrictions. At a certain point, Russia is indeed outstripped by a number of countries: Germany, England, France and even Austria-Hungary.

But this was only temporary.

Over time, Russia is ahead of all European countries in terms of the length of railways. Russia is getting the opportunity to use its record resource base for an industrial breakthrough. The solution of transport issues in the conditions of a superior resource base opens up the prospects for world leadership for Russia.

No revolution was needed. Roads were needed, and they were built.

This opinion of A. A. Borisyuk is quite consistent with the point of view of Paul Gregory, who called the construction of railways a condition for Russia's participation in the industrial revolution.

Note also that from 1895 to 1906 the river fleet increased 2 times. It was the largest in the world.

In 1916, more than 5 thousand kilometers of public railways were put into operation. The record has not been broken so far.

Documentation of the Ministry of Railways of the Russian Empire, stored in the Russian State Historical Archives, testifies that in 1916 a program was being developed for an even more accelerated construction of railways - over 6 thousand kilometers of new roads per year. Moreover, this is perceived as a minimum bar so as not to slow down the pace of economic development.

In Soviet times, these plans would prove to be impracticable.

Other numbers could be cited as well.

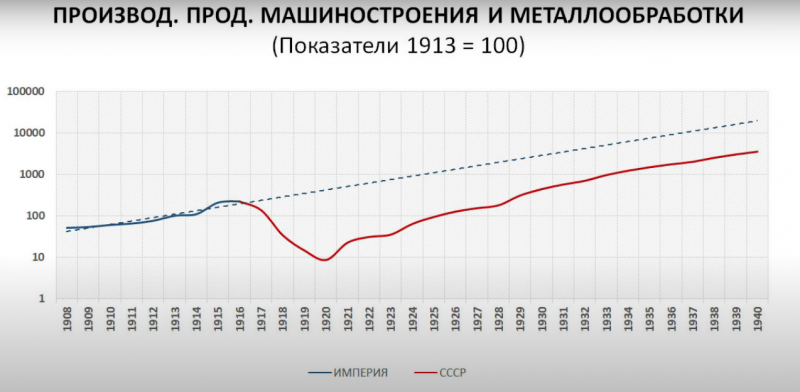

The graph clearly shows that the USSR reached its pre-revolutionary values in the field of mechanical engineering and metalworking only around 1929.

The same goes for steel smelting. Only by 1929 did the USSR reach pre-revolutionary indicators. Note that the growth of steel production in the Soviet Union is very close to the trend of the Russian Empire

The Soviet Union reached the pre-revolutionary level of coal production only by 1929. For ten years, the country has been restoring its positions lost after the revolutions of 1917.

Already at the beginning of the twentieth century - before the revolution - Russia began to outstrip the largest economies of Europe. A significant moment is the outstripping of the economy of France - one of the economic leaders of the XNUMXth century.

It should be noted that many, if not most, of the construction projects of the first five-year plans were designed even before the revolution.

For example, the famous "Magnitka" began in 1916, and at the end of 1917 the construction site stopped. The work was resumed only in 1927. The construction of the Dnieper Hydroelectric Power Station was supposed to begin in 1915, but the war prevented it.

All factories that produce railway locomotives to this day were built in pre-revolutionary Russia. It is enough to look at the year of their foundation.

For example: the Nevsky Machine-Building Plant was founded in 1857, the Kolomensky Plant - in 1863, the Bryansk Plant (BMZ) - in 1873, the Rostov Workshops of the Vladikavkaz Railway produced locomotives in 1896, the Lugansk Diesel Locomotive Plant (LPR) was founded in 1896.

They also designed the routing of the lines of the Moscow metro, which was planned to start building in 1920.

Separately, it should be said about the plan for the electrification of the country, which was developed back in 1909, the beginning of its implementation was scheduled for 1915, but due to the war, it was moved to 1920. After the revolution, the GOELRO plan was appropriated by the Bolsheviks.

As Paul Gregory points out:

Was there a famine in the Russian Empire?

Hunger in the empire has long been manipulated.

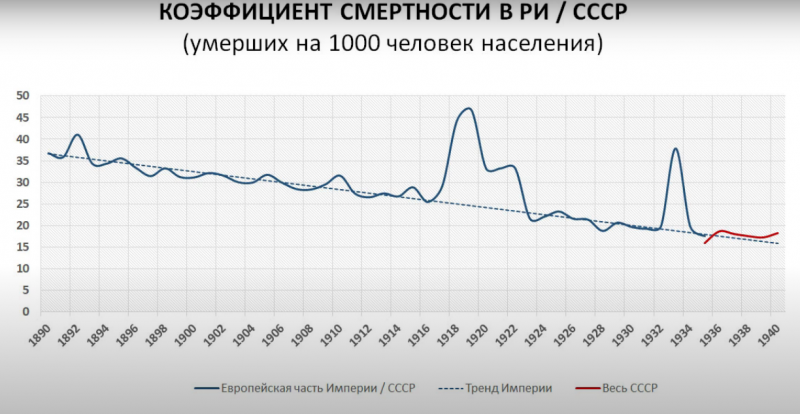

But mass hunger leads to leaps in mortality. They can be seen, for example, in the 1920s and 1930s. There are no such leaps in the empire. The mortality rate is constantly decreasing, and its fluctuations are decreasing. A transport system is being created at a record pace, which makes it possible to transfer food and medicine to the regions in need.

The graphics clearly show the absence of sharp outbreaks of an increase in mortality in the Russian Empire at the end of the XNUMXth - beginning of the XNUMXth centuries.

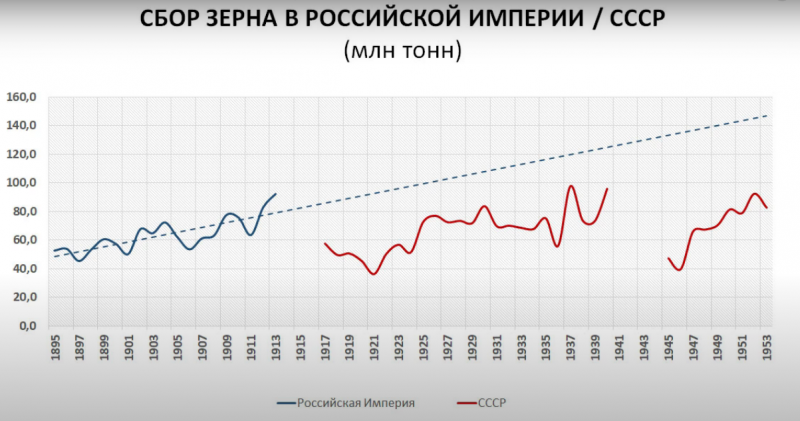

Along with this, a sharp increase in the volume of the harvest is recorded.

Grain yields, the main crops, are growing much faster than in comparable periods since the revolution. Moreover, the growth rate of the harvest outstrips the growth rate of the population.

After the revolution, the situation deteriorates, the volume of the harvest is sharply reduced. The country is gripped by hunger and widespread disease. The number of cases of typhus reaches 2 million per year. The incidence of malaria reaches almost 10 million people a year. However, these data were classified during the Soviet years.

Some people refer to references to hunger in various pre-revolutionary books or even dictionaries. But, as a rule, an important fact is overlooked: the very concept of hunger is quite broad. Hunger can be considered, for example, limited food to varying degrees, which really could be in the empire in times of poor harvest and which was successfully overcome. And you can count the peak values of starvation mortality, as in the 20s and 30s. There were no peak fluctuations in mortality characteristic of the Soviet Union in the Russian Empire.

Paul Gregory's data also indicate the impossibility of famine in the Russian Empire at the beginning of the twentieth century.

And more:

Welfare of citizens

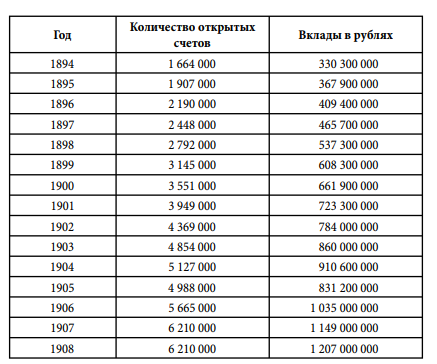

During the reign of Emperor Nicholas II, there has been a noticeable increase in the standard of living of the population.

In the last four years before the First World War, the number of newly established joint stock companies increased by 132%, and the capital invested in them almost quadrupled.

The progressive growth in the well-being of the population is clearly demonstrated by the following table of deposits in state savings banks:

In 1914, there were deposits in the state savings bank for 2 rubles.

According to Paul Gregory, before the outbreak of the First World War, Russian per capita income was one third of that in France and Germany and about 60% of that of Austria-Hungary. It should be added that the total amount of taxes (per resident in rubles) was:

Russia - 9,09

Austria - 21,47

France - 22,25

Germany - 22,26

England - 42,61.

Thus, the well-being of the inhabitants of Russia was lower than in France and Germany, but, taking into account the tax burden, it was approximately equal to the level of Austria-Hungary.

In terms of the absolute standard of living of the people, the USSR caught up with Tsarist Russia only by the beginning of the 1960s, having lost half a century, and in terms of relative, in comparison with other most developed countries, it never caught up with the Russian Empire.

Over the past 10 years before the First World War, the excess of state revenues over expenditures was expressed in the amount of 2 rubles.

This figure seems all the more impressive since during the reign of Emperor Nicholas II, railway tariffs were lowered and redemption payments for land that were transferred to the peasants from their former landowners in 1861, and in 1914, with the outbreak of war, and all types of drinking taxes, were canceled.

In conclusion

What can be said in conclusion?

The statistics are given above, and they eloquently indicate that the Russian Empire at the beginning of the twentieth century was not a backward country.

Among the leading countries of the world, Russia had very decent economic growth indicators, second only to the United States among the top countries, and a little. The indicators of the budget revenues of the country, which had very high growth rates, and in absolute terms were slightly inferior only to Germany, are also quite convincing.

In other words, at the beginning of the twentieth century, Russia was a rich country.

A number of pre-revolutionary economic indicators (steel smelting, pig iron smelting, coal mining, production of building materials, construction of railways) surpassed even the industrialization indicators of the 1930s in terms of their growth rates. At the same time, it is quite indicative that many of these indicators (including the production of mechanical engineering and metalworking products) in the Soviet Union reached the absolute values of the Russian Empire only by 1928–1929. That is, for ten (!) Years, the country's economy was only recovering after the revolutions of 1917.

The revolution and the unintelligible agrarian policy that followed it turned profitable Russian agriculture, which brought huge profits to the country, into unprofitable Soviet agriculture, when already in 1928-1929 the Soviet Union was forced to import grain for the first time in history. And no amount of new tractors saved the situation, since the peasantry found itself in a completely powerless position and was in no way motivated to increase the efficiency of their labor.

What could be the future of the Russian Empire if the crisis of 1917 was successfully passed?

One can only speculate about this hypothetically, nevertheless, general outlines can be given on the basis of those projects, the construction of which was planned before the revolutions. It is obvious that the country was waiting for an even more intensive construction of railways, massive electrification, the construction of industrial giants such as the Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works, DneproGES, etc.

The industrialization of the Russian Empire would have continued in 1920-1930, reaching more and more impressive absolute figures. Of course, it would have differed from the Soviet model in the direction of greater marketability and greater profits for the country. Most likely, light industry and the production of consumer goods would play a larger role in comparison with heavy industry. But this means that the country would make more money by improving the well-being of its citizens.

The revolutions of 1917 set the country back decades. The level of 1913 GDP of the USSR reached about 1928-1929. In these conditions, the notorious lag behind Western countries has increased significantly and demanded radical measures to create industrial power. And, since the evolutionary path of economic development was crossed out by revolutions, by the 1930s only a radical path of development remained. And he had a price, extremely high. But this is a topic for a separate conversation.

Information