How Ostarbeiters Preserved Labor Reichsmarks

This is not a politically correct topic. For historical propaganda is like a brick in a shop window.

The scarce literature on German politics in the occupied territories of the USSR certainly contains the theme of "theft into German slavery." German documents indicate that the Ostarbeiters in Germany were paid a salary, they even made savings, to which unexpectedly a lot of attention was devoted in the correspondence of several departments. The question of the savings of Ostarbeiters in Germany, where to store them and how to transfer them, arose in the fall of 1942, and the last document that we managed to find dates back to January 1945.

However, such themes, sometimes found in German documents, are interesting in that they reveal the springs and background of Nazi policy, the plans and intentions from which they proceeded in their actions.

So, the plans for the Ostarbeiters were much more far-reaching than just the "exploitation of slave labor." Apparently, they were trying to make one of the pillars of German power in the occupied territories.

Where did the Ostarbeiters get the money?

The Reishmarks of the Ostarbeiters were from wages. To avoid a long and useless discussion, it is necessary to outline the system of hiring and remuneration of Ostarbeiters.

Recruitment of workers in Ukraine began at the end of 1941, the first trains were sent to Germany in February 1942.

Upon arrival in Germany, the Ostarbeiters lived for some time in a sorting camp, from where they were dismantled by various firms and organizations. Workers could find themselves in a variety of jobs, from a large military factory to a small workshop or a utility company. This influenced their later life and work, since, for example, workers of a large military plant, as a rule, lived in a barrack camp belonging to the plant, but regularly received wages, while workers of small enterprises most often lived in private apartments, but could receive few and with delays.

On average, in 1942, a German worker received between 21,3 and 22,4 Reichsmarks per week.

The Ostarbeiter received 15,4 Reichsmarks per week, but at the same time 1,5 Reichsmarks were deducted from his salary for room and board per day or 10,5 Reichsmarks per week. 4,9 Reichsmarks were handed out. On a monthly basis, the German worker received from 217 to 225 Reichsmarks, the Ostaraibeiter - 100,5 Reichsmarks, 45 Reichsmarks were held and 55,5 Reichsmarks were issued.

100 Reichsmarks is a lot.

According to the official exchange rate (1 Reichsmark = 10 rubles) this is 1000 rubles. The average salary of workers at our military factories in 1942 was 600-700 rubles, and a skilled worker in an aircraft factory received about 800 rubles. Even after the deduction, the ostarbeiter had about 550 rubles left in his hands, which is more than workers in non-industrial sectors of the economy could receive in a month.

All further history revolved around these Reichsmarks issued to the Ostarbeiters in cash.

The need for savings

The recruitment of workers in Ukraine bore traces of impromptu, caused both by the transfer of the German economy to the regime of total mobilization, which took place in the spring of 1942, and by the massive conscription of German workers into the army. In fact, foreign workers had to replace this mobilization retirement.

Apparently, initially, they did not think about the financial problems associated with the Ostarbeiters. However, they appeared quickly.

The first problem is that the Ostarbeiters brought with them a certain amount of rubles, and in Ukraine, on July 6, 1942, the exchange of large denominations of rubles (10 rubles and more) for the currency of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine - Karbovanets began. On July 25, 1942, Reich Commissioner of Ukraine Erich Koch wrote to the leadership of the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine (Zentralwirtschaftsbank Ukraine, ZWB U) to change the Ostarbeiter rubles by the end of September 1942 (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 68, l. 125 ).

I could not find the end of this story, but, apparently, they changed the rubles for Reichsmarks at the official rate.

The question of the accumulations of Ostarbeiters arose immediately.

Firstly, receiving the Reichsmarks in their hands, the workers almost could not spend them, since in the Ostarbeiter camps, trade was poorly developed, and they did not have access to German stores, and German retail trade was regulated by the card system.

Secondly, the Ostarbeiters had no right to use German banks.

Thirdly, the export of cash outside the border of the Reich was prohibited; you could have with you no more than 10 Reichsmarks in small coin.

It turned out that the Ostarbeiters accumulated the money given to them, but they could not do anything with it.

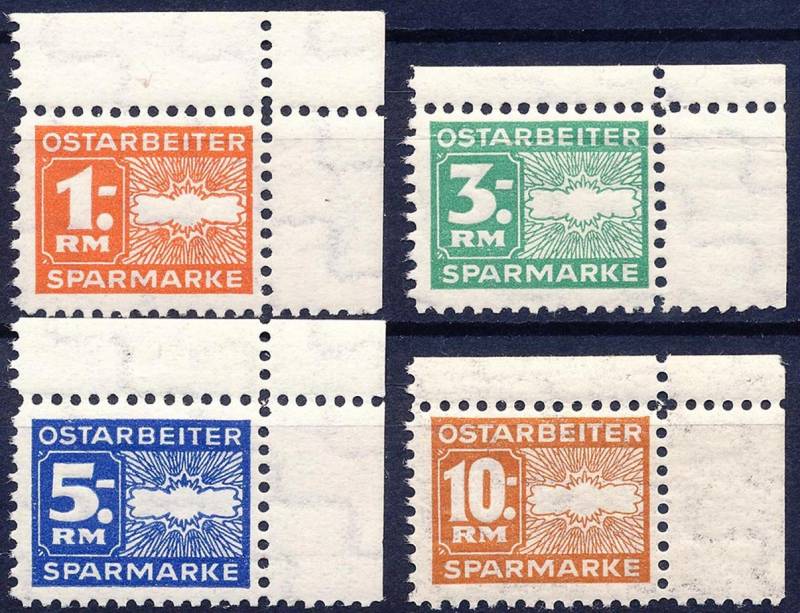

Already on August 5, 1942, the Berlin bureau of the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine made a proposal to create an accumulation system for Ostarbeiters. In Germany at that time, Sparmarke was used, worth 1, 3, 5 or 10 Reichsmarks, which were stuck on special accumulation cards signed with the name of the owner. The card, completely filled with stamps, could be given to the bank and received in cash or deposited in a savings account. The card had 135 fields and a minimum of 135 reichmarks could be accumulated. The bank suggested that the card should be sent to them if it has accumulated 90 Reichsmarks or more (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 68, l. 138-142).

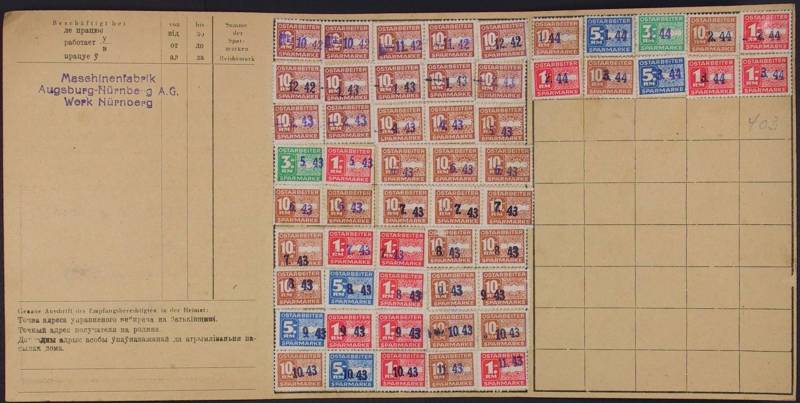

Turnover of accumulative cards with glued and marked stamps. The holder of this card has accumulated 1942 Reichsmarks from October 1944 to March 403

While the issue was being discussed in high authorities, some firms themselves started their own savings system for Ostarbeiters.

For example, at the request of the Ostarbeiters who worked there, Adam Opel AG in Rüsselsheim opened a cash desk in the work camp, where workers could deposit cash in order to avoid theft. The firm opened an account and a loan in a local bank for servicing cash transactions (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 69, l. 48).

The Central Economic Bank of Ukraine itself also accepted the savings of the Ostarbeiters. According to the bank's balance sheet for 1942 (the bank was opened on April 20, 1942), there were 32,3 million karbovanets of savings deposits in it, which, as follows from the note, were made up almost entirely by the deposits of ostarbeiters (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40 , d. 179, l. 65).

That is, by the end of 1942, the Ostarbeiters had contributed 3,2 million Reichsmarks to the bank.

Accumulate and transfer

In 1943, the system of saving labor Reichsmarks by Ostarbeiters took the following form.

It is well stated in the instructions issued both for the managers of enterprises, who were entrusted with receiving money from workers, and for the ostarbeiters themselves.

These instructions went through five editions.

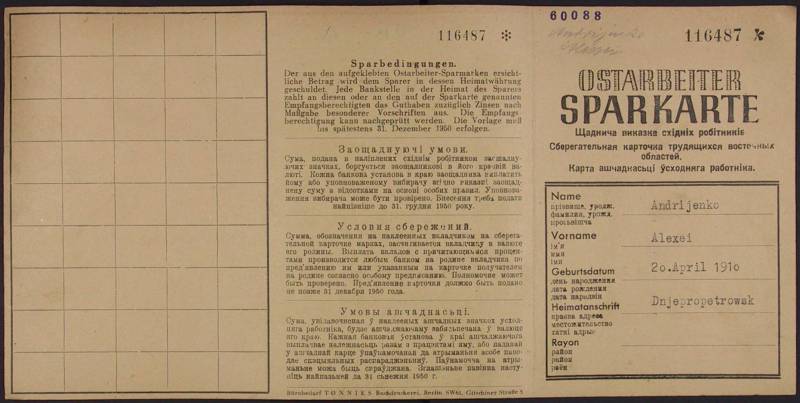

An Ostarbeiter could create a savings card, buy savings stamps that were pasted on the card. On the free field of the stamp, the month and year of the sticker were affixed with ink or a stamp. For example, for January 1943 - 1/43. This was necessary because interest was charged on the amount of savings - 2,5% per year.

Although the card was signed with the name of the owner, the lost cards were not restored, therefore it was recommended to give them to the manager of the enterprise for safekeeping.

Within 6 months after the first stamp was affixed and with an amount of 90 or more Reichsmarks, the card could be sent to the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine, which was done by the head of the enterprise. The card could be transferred to the passbook in its entirety, and it could also be sent to the bank for transfer to relatives. The address of the transfer was indicated on the card, the bank gave out half of the amount to relatives in cash in karbovanets, and the other half was credited to the savings book (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 179, l. 25). If the ostarbeiter deposited 50 or more Reichsmarks at a time, it could be immediately transferred to the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine to his savings account.

In the event of the death of an ostarbeiter, his card was sent to relatives and paid in cash by the Karbovans in full, but no more than 300 Reichsmarks (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 69, l. 11).

Also, an ostarbeiter, returning to Ukraine, could take his savings card with him. It was allowed to be carried across the border, and on the spot it could be exchanged for cash at the bank or transferred to a passbook.

Different points of view

The Central Economic Bank of Ukraine, or rather, its Berlin bureau, built a whole system for transferring the accumulations of ostarbeiters from Ukraine, which worked well, judging by the reporting, which will be discussed below.

The bank was supported by the Reichskommissariat Ukraine and the Reichsministry of the Eastern Occupied Territories, that is, Erich Koch and Alfred Rosenberg.

However, the attention of other departments was drawn to the accumulations of the ostarbeiters, both for political and economic reasons, since transfers and payments to Ukraine were subject to currency control. The Central Economic Bank of Ukraine was allowed to do this, since it was in fact a German bank that carried out transactions with Karbovanets. The Reich Ministry of Finance was generally not against such transfers, but limited them to a certain amount. In particular, the branches of the bank in Borisov and Pskov could carry out settlements on the accumulative cards of Ostarbeiters, but for the amount of no more than 20 Reichsmarks (RGVA, f. 000k, op. 1458, d. 40, l. 69).

Everything seemed to be going well, but in September 1943, a high authority suddenly intervened in the matter - the Party Chancellery of the NSDAP.

Judging by the letter dated September 14, 1943, the party office was not very well informed about the situation with the accumulations of the Ostarbeiters and demanded that measures be taken to limit the accumulations of the Ostarbeiters so that they would not accumulate large sums. The reason for the demand is the fear that the accumulations of Ostarbeiters will be used in speculation on the black market or in gambling (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 179, l. 22).

Many departments were involved in the correspondence with the Party Chancellery, and to the repeated letter from the Party Chancellery about the accumulations of the Ostarbeiters dated September 22, 1943, the Reich Ministry of Economics gave a rather phlegmatic, but very interesting answer on October 12, 1943.

The ministry's response was that the introduction of savings cards for Ostarbeiters pursued two goals: first, to prevent Ostarbeiters' earnings from entering the German market; the second - so that the accumulations would later be used for the economic development of those regions where the Ostarbeiters came from. Even, moreover, the recruitment of workers for work in Germany, as the Reich Ministry of Economics wrote in its reply to the NSDAP Party Chancellery, in itself, was carried out in order to develop the desire to accumulate among the population of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine.

True, the ministry acknowledged that the recruitment on this basis was generally unsuccessful (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 179, l. 30).

This stunning thesis is confirmed in other documents.

In a letter from the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine to the Reich Ministry of the Occupied Eastern Territories dated May 31, 1944, it is indicated that recruiting for work with a proposal to save money met with widespread and strong restraint among the population of the occupied territories of the USSR.

The bank's management explained this by the negative experience of the population in the past and suggested trying to agitate with more specific goals of accumulation that can be achieved quickly (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 179, l. 138).

Also, the instruction for Ostarbeiters (in three languages: German, Ukrainian and Russian), issued in September 1943, said:

(RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 179, l. 26).

In fact, it was an offer to work in Germany in order to start a business or economy in Ukraine using savings.

So, the position of the Reich Ministry of Economics, as well as the Reich Ministry of Armaments, was that they were generally interested in the influx of labor from the occupied eastern territories, since mobilization every month raked out more and more contingents of German workers. They needed a replacement and were willing to pay.

The Reichsministry of the Occupied Eastern Territories and the Reichskommissariat of Ukraine subordinate to it saw in the ostarbeiters, firstly, a source of funds for economic activity in Ukraine, since they could hardly expect large financial injections from Germany; secondly, as one might assume, they hoped in the future to turn the ostarbeiters who worked in Germany into the support of the German regime in the occupied territories, along with the Volksdeutsche and German colonists.

It is curious that even in May 1944, when there was nothing left of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, they did not abandon their ideas.

At the time of the intervention of the Party Chancellery, the Reich Ministry of Economics was already very skeptical about the plans of Rosenberg and his subordinates, and therefore in its response wrote that it would be worthwhile to allow the Ostarbeiters to consume in a larger volume (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 179, l. 30) ...

The Soviet offensive in Ukraine in late 1943 and early 1944 brought major changes.

On February 18, 1944, the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine applied to the Reich Ministry of Economics with a new problem. A large number of relatives of Ostarbeiters in Germany were evacuated from Ukraine either to the General Government (part of Poland and Western Ukraine) or to the Reichskommissariat Ostland. The system for transferring Ostarbeiter savings from Ukraine did not apply to these regions, but the workers themselves expressed a desire to transfer their funds to relatives at their new place of residence. Payments were to be made through the Central Bank of Lemberg (Lvov) and the Ostland Community Bank in Riga (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 69, l. 20).

The ministry responded slowly, only on March 23, 1944, but favorably. Minister Walter Funk wrote to the bank's management that he agreed with their proposals and gave the necessary orders to the Office of Foreign Exchange Control in Berlin (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 69, l. 22).

The rapid advance of the front forced us to make more and more changes.

The Ostarbeiter Savings Instruction, issued in July 1944, already states that large purchases, medical and medical expenses, vacation expenses, payments to support relatives in Germany and other similar purposes can be paid from the passbook on instructions ( RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 69, l. 77).

The previous procedure for transferring abroad was retained, but not so pronounced, since the Reichskommissariat Ukraine actually did not exist anymore, and many of the workers' relatives either died or ended up behind the front line.

In general, the Reich Minister of Economics turned out to be right in assessing the situation.

Accumulation results

The surviving documents contain two reports on the size of the accumulation of Ostarbeiters.

The first of them was drawn up by the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine on October 22, 1943, which sold accumulative stamps for 16,5 million Reichsmarks, the bank received accumulative cards for 932 thousand Reichsmarks, of which 466 thousand Reichsmarks were paid to relatives in Ukraine in cash (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 179, l. 27).

The second report is contained in a letter from the Reich Minister of the Occupied Eastern Territories, Alfred Rosenberg, dated February 29, 1944.

It says that out of 22,3 million Reichsmark savings marks, about 20 million are for ostarbeiters. Of these, 12,9 million Reichsmarks were invested in bonds at 3,5%, 500 thousand were in the Postal Savings Banks. 8,8 million Reichsmarks were paid to Ukraine, 50 thousand - to Belarus and another 50 thousand - to the areas of economic inspections "Mitte" and "Nord".

Rosenberg wrote that out of 1,8 million Ostarbeiters, about 25% participated in the accumulation, and the average amount of accumulations was 45 Reichsmarks (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40, d. 69, l. 53).

Somehow, all this does not fit with the thesis about "theft into slavery."

25% of the 1,8 million Ostarbeiters are 450 thousand people who saved their labor Reichsmarks. These were definitely not “driven into slavery”, but they went to work because they sided with Germany and they needed money to get a better job under the occupation power.

It seems that a significant, if not most, part of the Ostarbeiters went to work quite voluntarily, out of anti-Soviet motives and views, knowing full well what prospects this gives them. It's just that after the war it became very unprofitable to remember it.

The relatives of these Ostarbeiters supported them.

This is indicated by the fact that, when the Soviet troops attacked, they rushed to flee with the Germans to Poland or the Baltic States, and this is also indicated by a sharp jump in payments, from 0,9 to 8,8 million Reichsmarks between October 1943 and February 1944. , that is, in just five months.

The reason is quite obvious: money is needed for the escape of relatives. Hearing about the collapse of the Eastern Front, these ostarbeiters began to besiege the heads of enterprises with demands to send their savings to their relatives immediately. Apparently, at this time they were allowed to translate and less than 90 Reichsmarks.

The end of this story was tragicomic, in the spirit of the merciless German order.

At the very end of January 1945, just in the days when the front collapsed and Soviet troops rushed to the offensive towards the borders of Germany, the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine, shrinking to its Berlin bureau, entered into an agreement with another bank - Bank der Deutscher Arbeit AG in Berlin and gave him all the accounts and savings of the Ostarbeiters.

On January 29, 1945, the leadership of the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine wrote in writing to the Reich Minister of the Occupied Eastern Territories Alfred Rosenberg and asked him to write an order on the transfer of savings to this new bank, and that they would be paid in Reichsmarks (RGVA, f. 1458k, op. 40 , d. 179, l. 238).

In fact, a non-existent bank asks, in fact, a fictitious ministry to issue an order, because order and accountability are sacred, even if the rumble of Russian cannons is already heard.

Information