Friendship and friendship between combat opponents

The Caucasus, at first glance, could not become the birthplace of such a deep tradition with enormous social subtext as kunachism. Too many wars and contradictions rush over these mountains, peoples speak too different languages to become the ground for the cultivation of a tradition that puts friendship on a par with kinship, if not higher. But, perhaps, despite the obvious paradox, that is why in the Caucasus, kunachism appeared as a thin but strong thread between different villages, villages and entire nations. If you rise above the personal level, then kunachstvo becomes an interethnic instrument, which, however, with a sin in half, but sometimes worked. The custom itself does not give in to dating. At least he is over five hundred years old.

How did they become kunaks?

It is generally accepted that kunachism is a kind of deep modernization of hospitality, but this judgment is too simplistic and does not reflect all the contrasting realities of the Caucasus. Of course, a guest could become a kunak, but life is more complicated. They became kunaks after joint wanderings, they became people close in spirit or status. Sometimes even the outstanding warriors from the warring camps, learning about the rumor hovering about them among the people, met in a secret meeting with each other and, subject to sympathy, became kunaks. A simple person from the street in kunaki would never have crammed, because with this title a whole range of responsible duties was acquired.

It is worth mentioning, of course, that “kunak” in translation from Turkic means “guest”. But the Vainakh peoples have a very consonant concept of “konakh”, meaning “worthy man”. And a guest can not always be worthy, therefore, kunak is deeper than the custom of hospitality.

When the two men decided to become kunaks, then, of course, this arrangement was verbal. However, kunakism itself was held together by a certain rite, which among different ethnic groups had some of its own nuances, but the overall picture was similar. Kunaki took a cup of milk, wine or beer, which, for example, was sacred among Ossetians, and swore before God to be faithful friends and brothers. Sometimes a silver or gold coin was thrown into the bowl as a sign that their brotherhood would never rust.

Duties and privileges of the kunaks

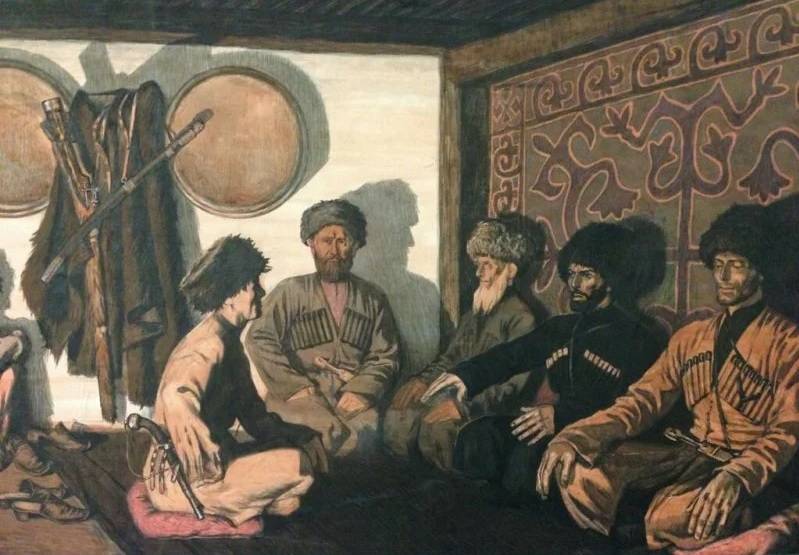

Kunaki until the end of life were obliged to protect each other and support. And just in defense and reveals the deep meaning of kunachstva. If a simple guest was protected by the owner only at his home, then the kunak could count on the help of a friend at any time of the day or night and in any land in which fate would throw him. That is why, if anyone was hunting kunak, then it was more convenient to slaughter him on a mountain road, because if he were in a friend’s house, the enemy would have to storm the whole house. From here, by the way, is one of the mountain sayings: "A friend in a foreign land is a reliable fortress."

Wealthy highlanders always attached a special room to their houses, the so-called kunatskaya, where a dear friend was always waiting for a clean, dry bed and a hot lunch (breakfast, dinner) at any time of the day. For some nations, it was customary to leave a portion separately for dinner or lunch in case of the arrival of kunak. Moreover, if the means allowed, just in case they kept a set of outerwear for kunak.

Of course, the kunaki exchanged gifts. It was even a kind of competition, everyone tried to present a more refined gift. The presence of kunaks at all celebrations of the family was mandatory, wherever they were. The Kunak families were also close to each other. This was emphasized by the fact that in the event of the death of one of the kunaks, depending on the circumstances, his friend was obliged to take the family of the deceased into custody and protection. Sometimes kunachstvo was inherited. At this moment, the Kunak families practically merged into one family.

Kunachestvo as an Institute of Interethnic Communication

In the war and strife, everlasting in the Caucasus, kunachism was a unique phenomenon of interethnic and even trade relations. Kunaki could act as a kind of diplomats, sales agents and bodyguards. After all, a good responsible kunak escorted a friend not only to the borders of his village, but sometimes because of the need, straight to the next friendly village. And the prosperous highlanders had many kunaks. In difficult conditions of civil strife, such relations were a kind of security points.

For example, almost until the middle of the 19th century, i.e. Before the official end of the Caucasian War, Armenian merchants used exactly the same kunatsky network during long crossings through the Caucasus Mountains with convoys of their goods. Kunaki met them on the way to the village or village and escorted to the borders of the next friendly village. Ossetians, Vainakhs, and Circassians used such connections ...

And, of course, dear guests from distant lands were always seated at a rich table. And since in those days no one had ever heard of any clubs and other public institutions, the kunak feast attracted the whole village to find out news, look at the goods, and perhaps, to establish friendships themselves.

Famous Russian Kunaki

Kunachestvo was deeply reflected not only in the folklore of the peoples of the Caucasus, but also in classical Russian literature. For example, the great Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov, who served in the Caucasus, after a bloody battle near the Valerik River, wrote the poem of the same name “Valerik”:

Hit on the shoulder; he was

My kunak: I asked him

How is this place named?

He answered me: Valerik,

And translate into your language,

So there will be a river of death: right,

Given by ancient people.

Seismism was reflected in Lermontov’s novel “Hero of Our Time”:

Here are reflected and the strict mandatory observance of the unspoken laws of kunachism, and the interethnic nature of this tradition. It is also worth considering that Lermontov himself wrote about this, which was a kunak to many highlanders. By the way, this can partly explain the fact that the military officer, veteran Valerika periodically left the camp, leaving for distant villages, and returned safe and sound.

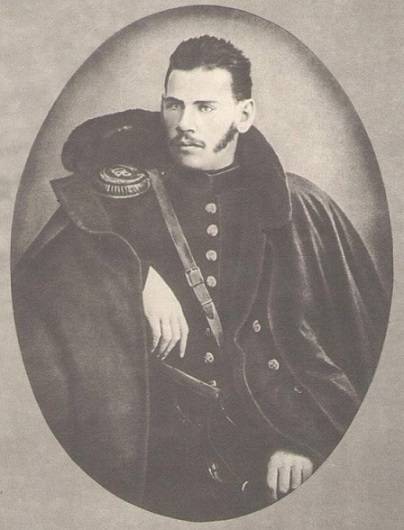

Another equally famous kunak was the brilliant writer Leo Tolstoy, who came to the Caucasus in 1851 with the rank of cadet of the 4th battery of the 20th artillery brigade. After some time, being on the Terek, the young cunker became friends with a Chechen named Sado. Friendship was secured by a kunatsk oath. Since then, Sado has become indispensable for the young Leo. He repeatedly saved the writer’s life, helped in heavy army service, and once he played the money recklessly lost by Tolstoy in cards.

Equality on opposite sides of the front

Despite the raging Caucasian war, kunak relations quickly ensued between the Russians and the highlanders. Even on the banks of the Terek, where Cossack villages and villages stood across the river, kunaki, catching a moment of calm, went to visit. These unspoken relations by the authorities were hardly suppressed, because they were another channel for exchanging information and building diplomatic bridges. The Highlanders came to the villages, and the Russians to the villages.

One of the most tragic and therefore noteworthy examples of kunachism was the friendship of the centurion Andrei Leontyevich Grechishkin and the senior prince of the Temirgoy tribe Dzhembulat (Dzhambulat). Andrei, who grew up in the family of a linear Cossack in the village of Tiflis (now Tbilisskaya), had already earned the respect of his older comrades at a young age, and his rumor was carried with reverence. On the other side of the Caucasian cordon line, the fame of Prince Djembulat, who was considered the best warrior of the North Caucasus, was booming.

When rumors of a young and brave centurion Grechishkin came to Dzhembulat, he decided to meet his enemy personally. Again, through the kunaks, scouts and secret communication channels, we managed to arrange a meeting in the swampy and secret places of the Kuban River. Two courageous people, after a short conversation, as they say, penetrated. Soon they became kunaks. Grechishkin and Dzhembulat secretly went to visit each other, exchanged gifts on Christian and Muslim holidays, while remaining implacable enemies on the battlefield. Friends shared everything except politics and service. At the same time, everyone in the camp of the Temirgoyevites and the Cossack army knew about this friendship, but no one dared to reproach them.

In 1829, reports spread along the Caucasian line that a large mountain detachment was preparing a raid on the Cossack villages. Location information was extremely small. Therefore, on September 14, Lieutenant Colonel Vassmund ordered the centurion Grechishkin with fifty Cossacks to conduct reconnaissance on the other side of the Kuban. On the same day, fifty performed. Then no one knew that the Cossacks saw the good centurion for the last time.

In the area of the modern Peschany farm on the 2nd Zelenchuk River, Grechishkin’s detachment ran into six hundred horsemen under the Temirgoy badges. Having barely managed to send one Cossack with intelligence data, the centurion with the rest was surrounded and was forced to accept a suicidal battle. But the first attack of the Highlanders choked. Therefore, Djembulat, who valued courage, ordered to find out who was the senior of this detachment. What was his amazement when he heard the native voice of Andrei Kunak.

Dzembulat immediately invited him to surrender. The centurion lamented that it was time for the kunak to know that the hereditary ruler would never do this. The prince agreed and nodded somewhat bashfully. Returning to his camp, Dzhembulat began to convince his elders to leave the Cossack detachment alone, since there would be no profit from them, and military fame could not be won with such and such forces. But embittered highlanders began to rebuke the prince that he dared to succumb to his feelings.

As a result, Prince Djembulat himself was the first to rush into the next attack. In the first minutes of the assault, Dzhembulat was seriously wounded, and he was carried in his arms from the battlefield. The vengeful warriors of the prince hacked Grechishkin beyond recognition, but the raid by that time was already doomed. Neither military glory nor profit, as Dzembulat predicted, the Temirgoyites did not find that September. It was as if the sin of breaking a noble tradition had cursed that campaign of the highlanders.

Information