Union of Hope December 14, 1825

Why did the Decembrists lose? But really, why? After all, the attempted armed coup made by the liberal conspirators seemed to have every chance of success, and no worse than a quarter century before.

Fake News Against the Truth

So, first of all, the situation of interregnum worked for the rebels after the death of Alexander I. The general tension in the Russian elite was especially aggravated after the inexplicable majority of inhabitants of the empire renounced the right to the throne of the elder brother of the late tsar Konstantin Pavlovich. Many of the subjects had already sworn allegiance to him as a legitimate sovereign.

A situation has formed in the country, which today would be called an information vacuum. Not only the “mob”, but also a significant part of the nobility and even court circles were ignorant of the motives of the candidates for the throne and the future monarchy. Rumors and the most incredible guesses fueled the imagination of the subjects left without higher care.

Truth often looks far less convincing than a lie. At one time, reliable information from the government of Boris Godunov about Grishka Otrepiev could not stand the competition with an entertaining legend about the miraculously saved Tsarevich Dimitri.

Here is the official version of the emperor’s refusal of the right to the throne and the need for a new oath to his brother, although it corresponded to the true state of affairs, but in the eyes of the average man it looked like an impudent deception. At the same time, all kinds of “fakes”, for example, that Tsar Konstantin was going from Warsaw to the capital to protect his throne, or even hidden in the Senate building, on the contrary, were unconditionally accepted on faith.

This greatly facilitated the task of agitation among the soldiers of the guard regiments, whom the officers involved in the plot urged not to swear allegiance to the "usurper" Nikolai, but to defend the true sovereign. In this regard, the usual definition of the rebellion of 1825 as an anti-monarchist speech should be considered at least conditional, because only the top of the Decembrists considered it as such.

Often, the masses were involved in political movements by deception, promises, false or falsely understood slogans, or baseless expectations of the participants themselves. Often, the interests of various forces involved in the movement coincided only partly for a while, but the case when the goals of leaders and their supporters were directly opposed at first should be recognized as unique not only in the domestic, but, perhaps, in the world stories.

If the instigators of the coup set the task of changing the political system, scrapping the existing political system, then for the personnel of the rebel regiments the motive was precisely the restoration of the rule of law, which was threatened by the insidious "thief of the throne" Nikolai. So did the townspeople.

It is for this reason that the Petersburgers gathered around the rebel горяч s heartfelt sympathy for them, and the following calls came from the crowd to the newly minted autocrat: “Come here, impostor, we will show you how to take away someone else's!” When Metropolitan Seraphim approached the rebels, convincing them that Konstantin was in Warsaw, they did not believe him: “No, he’s not in Warsaw, but at the last station in chains ... Pass him here! .. Cheers, Konstantin!”

Shouting "Hooray, Constantine!" that day many were ready

What can we say about the lower ranks of the guard regiments or the townsfolk, even if some officers, the Decembrists, saw what was happening as a statement in support of the legitimate sovereign. For example, Prince Dmitry Shchepin-Rostovsky, whose scrutiny was taken to the Moscow regiment, did not think about any restriction of the monarchy, but went to defend the right to the throne of the legitimate emperor Constantine.

The uprising on Senate Square was a military coup, taking the form of suppressing an imaginary coup, a rebellion under the guise of curbing the rebels.

Novels and Emptiness

In this regard, the question arises: how, in the light of all these circumstances, the Decembrists would be able to maintain power if successful. But, as they say, this is a completely different story, but we will try not to go beyond the events of December 14th. And on this day, we repeat, the chances of the conspirators to win were very high.

Despite organizational friability and flaws in planning (which we will talk about in more detail later), the Decembrists nevertheless rather consistently prepared for the coup. Although Nikolai was warned about the conspiracy, in spite of common wisdom, he was not at all “armed” because he had no one to arm. Accordingly, the grand duke did not even have and could not have any even the most approximate plan of action or counter-actions.

The real power in the capital belonged to Governor-General Mikhail Miloradovich, who was subordinate to the troops and the secret police. Miloradovich openly supported Konstantin and prevented the accession to the throne of his younger brother. Nicholas, of course, remembered that the head of the conspiracy against Paul I, Count Peter Palen, on the fateful days of March 1801, also served as the St. Petersburg military governor, and this analogy could not but worry him.

Governor-General of St. Petersburg Mikhail Miloradovich

With information on the anti-government intentions of the main conspirators and direct indications on their account, Governor-General Miloradovich was almost demonstratively inactive. He was inactive even on December 13, when the head of the Southern Society, Colonel Pavel Pestel, was arrested at the headquarters of the 2nd Army in Tulchin (now the Vinnytsia region of Ukraine).

At this time, in the capital of the empire, with the full connivance of the police, the head of the Northern Society Kondraty Ryleyev was completing preparations for the uprising. However, the author does not share the version that Miloradovich almost stood behind the coup. Mikhail Andreevich felt too much power for himself to exchange for conspiratorial games with figures like Ryleyev and his insignificant associates. He knew about the maturing conspiracy and was not averse to using it in his interests - nothing more.

But if, unlike Miloradovich, other generals and dignitaries did not dare to openly front up against Nicholas, this did not mean that the future emperor could rely on them. And this is another argument in favor of the success of the uprising: the conspirators clearly lacked “thick epaulettes” in their ranks, but they at least firmly relied on the “company commanders” and most of them already confirmed their resolve during the speech.

Nikolai did not have this either. A vacuum formed around him: any of the officers or generals surrounding him could be a traitor. “The day after tomorrow, in the morning, I am either a sovereign or without breathing,” the Grand Duke admitted in a letter.

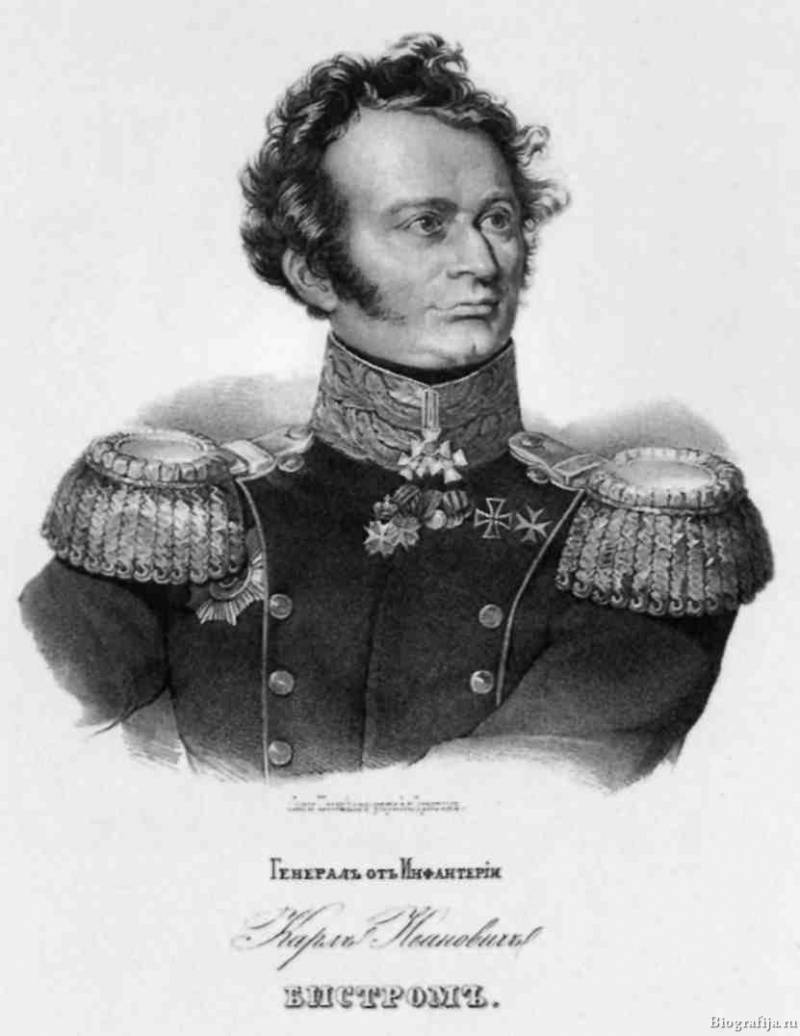

In this regard, the position of the guards infantry commander Karl Bistrom, then still only Lieutenant General, with all his merits and long service, is noteworthy. Both adjutants of General Evgeny Obolensky and Yakov Rostovtsev were among the conspirators, Karl Ivanovich himself declared that he would not swear to anyone but Konstantin.

Bistrom, sharing the political preferences of his boss Miloradovich, was obviously afraid that the southern temperament and self-confidence of the military governor would harm him and the cause of the ill-wishers of Nikolai. We can not ignore that Bistrom had a personal reserve in the form of a regiment of guards rangers, whom he commanded for several years. At the decisive moment, the general was ready to throw his trump card on the table.

On December 14, Bistrom laid down the oath of the rangers and, taking a truly Mkhatov pause, he waited in which direction the scales would lean. Ostzey’s composure did not disappoint Karl Ivanovich, and although the emperor himself did not conceal that Bistrom’s behavior on the day of the coup seemed at least strange, no one made specific claims to the general, and his subsequent career was quite successful.

In light of the foregoing, we can assume that the oath to Nikolai, scheduled for December 14, resulted in an experiment, the result of which for all of its participants seemed unpredictable. Only the process of oath could show who is who. Nikolai was left with the worst - to wait. He did everything possible: he approached the date of the oath, promised promises for officers in the event of a successful outcome, but the opposite side, if successful, could offer them their bonuses.

All initiative was in the hands of opponents of the monarchy. Unlike Nikolai, by the morning of December 14, the putschists had fairly complete information about what was happening in the garrison, the mood of the lower ranks and officers, and had the opportunity to coordinate their efforts.

Moreover, as the “dictator” of the uprising, Prince Sergey Trubetskoy, writes in his notes, the conspirators were well informed of all the actions of the Grand Duke and the entire military authorities. Under these conditions, the Decembrists could only lose to themselves. Which they did.

Do you have a plan, Mr. Fix?

In school textbooks, the actions of the rebels on December 14 look like a mysterious standing on Senate Square in anticipation of the gathering of government troops and as a result of their defeat. Just as M.V. Nechkina once did, so today Y. A. Gordin is trying to refute the established opinion about the inaction of the rebels.

So, Nechkina noted that it was “not standing, but the process of collecting parts”, which, in our opinion, does not fundamentally change anything in the picture of events. Gordin adds emotion, emphasizing that the rebel units fought their way to the square, but this again adds nothing to the essence of the matter.

In the book “Decembrists and Their Time”, V. A. Fedorov adheres to the “school” version, indicating that the Decembrists had every opportunity to capture the Winter Palace, the Peter and Paul Fortress, the Arsenal and even arrest Nikolai and his family. But they limited themselves to active defense and, not daring to go on the offensive, took a waiting position, which allowed Nicholas I to gather the necessary military forces.

The researcher notes a number of other tactical errors, in particular, "an order to assemble in Senate Square, but without an exact indication of what to do next." But in this case, who exactly made tactical mistakes, who specifically gave the order to gather for the Senate?

Fedorov reports that the first plan of the uprising was developed by Trubetskoy: its general meaning was to bring the regiments out of the city even before Konstantin renounced, and, relying on armed force, demand from the government to introduce a constitution and representative government. The historian, noting the feasibility of this plan, indicates that he was rejected, and the plan of Ryleyev and Pushchin was adopted, according to which, with the beginning of the oath, the indignant units were brought to Senate Square in order to force the Senate to declare the Manifesto to destroy the old government.

Gordin’s Ryleyev-Pushchin’s plan becomes ... Trubetskoy’s plan, more precisely, a “combat plan”, apparently, in contrast to the previous version of the military demonstration presented by the prince. This plan of Trubetskoy allegedly consisted of two main components: the first - the capture of the palace by an attack group and the arrest of Nikolai with his family and generals, the second - the concentration of all other forces in the Senate, the establishment of control over the Senate building, the subsequent strikes in the right directions - the seizure of the fortress, the arsenal.

“With this plan in mind, Trubetskoy went to Ryleyev in the evening of December 12,” Gordin reports.

Not having the opportunity to "get into the head" of Trubetskoy, let us give the floor to the prince himself. During the investigation, the dictator showed the following: “Regarding the routine made about the actions of December 14, I did not change anything under my previous assumption; that is, that the Naval crew go to the Izmailovsky regiment, this one to the Moscow, but the Leib-Grenadier and Finland should go directly to Senate Square, where the others would come. ”

However, this is a completely different plan! And Gordin mentions him, though as a preliminary and without naming the author. It was based on the following system of actions: the first units that refused to swear take a certain route from the barracks to the barracks and take others by their example, and then follow to Senate Square. “But this plan, because of its bulkiness, slowness and uncertainty, did not suit Ryleev at all,” Gordin emphasizes, “Trubetskoy accepted him for want of a better one ...”

But what is cumbersome, indefinite and slow in this regard? On the contrary, the approach of the rebel forces would have a decisive effect on doubters from other regiments and would speed up and intensify the concentration of rebel forces many times over. In this embodiment, the gathering of troops instead of passive waiting in the square implied vigorous action.

From the starting point of the movement, the Naval crew, to the Izmailovsky barracks, about fifteen minutes walk, and from there along the Fontanka from half an hour from the force to the Moscow regiment. Trubetskoy completes the presentation of the plan with the addition of the Moscow Regiment and, for obvious reasons, says nothing about the plans for the Winter Palace.

However, it is obvious that parts of the rebels along Gorokhovaya Street went to the Admiralty, but from there they could turn left to the Senate, and they could turn right to the Winter Palace. As for the Senate, the units located away from this route were supposed to advance there: the Finnish regiment was located on Vasilievsky Island, and the Life Guards on the Petersburg side.

It is understood that these are only outline of the plan, but its logic is quite clear. Meanwhile, they want to assure us that, in the absence of another, Trubetskoy accepted the unknown version, which came from somewhere. However, the prince not only does not hide his authorship, moreover, from his words it follows that this tactic was proposed to him before, and he continued to insist on it.

Senate Factor

It is generally accepted that the rebels intended to force the Senate to abandon the oath to Nicholas and proclaim the Manifesto they had prepared, but the Grand Duke ahead of them, reassigning the date of the oath to an earlier time. Given the fact that the leaders of the uprising knew about the oath being transferred and had the opportunity to respond to the changing situation, standing in the square in front of the empty Senate seems absurd. It turns out that the Decembrists, not having prepared the plan “B”, continued to act according to the plan “A”, realizing that it was not feasible ?!

Gordin is trying to resolve this collision, noting that the Decembrists did not expect to catch the Senate oath with the soldiers on the square.

Is it so? Nechkina, relying on the numerous testimonies of the coup participants, points out that the Decembrists intended to force the Senate to take their side, which, of course, does not mean sending couriers, but forcefully seizing the building along with dignitaries sitting there and directly affecting them.

The new building of the Governing Senate (pictured) appeared after the Decembrists' speech, and earlier there was the house of the merchant Kusovnikova

The refusal of the oath of the Senate could serve as a powerful catalyst for the uprising and determine the position of the hesitant among the lower ranks, and among the highest dignitaries and generals. But as soon as difficulties arose that required adjustment of actions, Ryleyev and his entourage somehow very easily rejected this promising option, giving the senators the opportunity to swear allegiance to Nikolai, which made it very difficult to achieve their goals.

The presence of a Senate courier service is, of course, wonderful, but what would prevent the senators, who had just sworn allegiance to Emperor Nicholas, from ordering these couriers to be sent down the stairs? Even the seizure of the Winter Palace and the arrest of the king would not change much in the situation. Only one circumstance could radically affect the position of the Senate and the entire balance of power - the death of the sovereign.

Gordin believes that the “Ryleyev-Trubetskoy group” was not going to leave Nikolai in power at all: “No wonder the secret element of the tactical plan was regicide, the physical elimination of Nikolai.” But in another place, the historian indicates that for Ryleyev the regicide should have preceded the capture of the palace or coincided with it in time, however, Trubetskoy learned about this plan only during the investigation.

Then what is this “Trubetskoy's plan”, the author of which did not know about its most important element, and what kind of group is “Ryleyev-Trubetskoy”, one of whose members is hiding his plan from the other? It is known that Trubetskoy considered it necessary to conduct a trial of Nicholas, but this implied the realization of the original intention - to force the Senate to side with the putschists. Ryleyev hoped to "deal" with Nikolai in haste without trial or investigation. With this turn of events, the oath of senators became a secondary factor that could be ignored.

According to Gordin, the most important role in the rebellion was assigned to the dragoon captain Alexander Yakubovich, who undertook to lead the Guards crew and go to the palace, but allegedly refused because of jealousy for the supremacy of Trubetskoy. The historian has repeatedly emphasized that it was the irresponsible behavior of Yakubovich and Colonel Alexander Bulatov, who was to lead the grenadier regiment well known to him, that caused the failure of the coup.

On November 12, at a meeting with Ryleyev, Bulatov and Yakubovich were elected deputy "dictators", and Lieutenant Prince Obolensky was elected chief of staff. Obviously, for the sake of the interests of the case, these characters were required to closely interact with each other. Meanwhile, Trubetskoy testified that he had seen Yakubovich once in his life and would prefer to never see him again.

An even more entertaining story happened with Bulatov. At about 10 a.m. on December 14, according to the testimony of the colonel himself, he came to Ryleyev and saw Obolensky for the first time: "He was terribly happy about my arrival, and when we saw him for the first time, we shook hands, shook hands."

Meeting of the Decembrists. Is it any wonder that the dictator did not know his deputies, and those - the dictator?

So, the uprising has already begun, and the chief of staff for the first time sees the "deputy dictator", while Obolensky is "terribly happy." Just what? After all, Bulatov should lead the Life Guards out of the barracks, and not drive around town! It seems that the chief of staff does not know anything about such an assignment. Moreover, the “deputy dictator” declares to his comrades-in-arms that he will not “dirty himself” if the rebels do not collect enough parts!

That is, instead of bringing troops, the colonel demands this from Ryleyev and Co. We add that Bulatov does not need to bother and cast a shadow over the fence: he himself confessed to the emperor, insisted on his arrest, and subsequently committed suicide in the Peter and Paul Fortress.

So what actually preceded the uprising of December 14 and what predetermined its bizarre move and tragic ending? About this - in the second part of the story.

To be continued ...

Information