World War I could have been avoided

After Gavrila 28 Principle June 1914 committed the assassination of the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo, the opportunity to prevent war persisted, and neither Austria nor Germany considered this war to be inevitable.

After Gavrila 28 Principle June 1914 committed the assassination of the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo, the opportunity to prevent war persisted, and neither Austria nor Germany considered this war to be inevitable.Between the day when the Archduke was murdered and the announcement of Austria-Hungary of Serbia’s ultimatum three weeks passed. The anxiety that arose after this event soon subsided, and the Austrian government hastened to assure St. Petersburg that it did not intend to take any military action. The fact that Germany did not even think of fighting at the beginning of July is evidenced by the fact that a week after the assassination of the Archduke Kaiser Wilhelm II set off for the summer “rest” in the Norwegian fjords. There was a political lull, the usual for the summer season. The ministers, members of parliament, and high-ranking government and military officials went on vacation. The tragedy in Sarajevo didn’t particularly disturb anyone in Russia: the majority of political leaders were deep in the problems of internal life. All spoiled the event that happened in mid-July. In those days, taking advantage of the parliamentary vacation, President of the French Republic Raymond Poincaré and the Prime Minister and, at the same time, Foreign Minister René Viviani paid an official visit to Nikolay II, arriving in Russia aboard a French ship of the line. The meeting took place on July 7-10 (20-23) at the summer residence of Tsar Peterhof. Early in the morning of July 7 (20), the French guests switched from the battleship anchored in Kronstadt to the royal yacht, which delivered them to Peterhof. After three days of talks, banquets and receptions, interspersed with a visit to the traditional summer maneuvers of the guards regiments and units of the St. Petersburg Military District, the French visitors returned to their battleship and departed for Scandinavia. However, despite the political lull, this meeting did not go unnoticed by the intelligence services of the Central Powers. This visit clearly testified: Russia and France are preparing something, and this is preparing something against them.

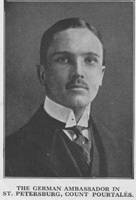

German Ambassador to Russia, Count Friedrich von Pourtales (1853 – 1928)

German Ambassador to Russia, Count Friedrich von Pourtales (1853 – 1928)We must directly admit that Nikolai did not want a war and tried his best to prevent it from beginning. In contrast, the highest diplomatic and military officials were in favor of military operations and tried to exert strong pressure on Nicholas. As soon as a telegram arrived from Belgrade on July 24 (11), 1914 that Austria-Hungary presented an ultimatum to Serbia, Sazonov joyfully exclaimed: “Yes, this is a European war.” On the same day at breakfast with the French ambassador, who was also attended by the English ambassador, Sazonov urged the Allies to take decisive action. And at three in the afternoon he demanded that a meeting of the Council of Ministers be convened, at which he raised the question of demonstrative military preparations. At this meeting, it was decided to mobilize four districts against Austria: Odessa, Kiev, Moscow and Kazan, as well as the Black Sea, and, strangely, the Baltic fleet. The latter was already a threat not so much of Austria-Hungary, which had access only to the Adriatic, but against Germany, the sea border with which was just across the Baltic Sea. In addition, the Council of Ministers proposed introducing from July 26 (13) throughout the country a "provision on the preparatory period for the war."

25 (12) July Austria-Hungary said it was refusing to extend the deadline for a response to Serbia. The latter, in its response to the advice of Russia, expressed its readiness to meet the Austrian requirements for 90%. Only the requirement of entry of officials and military to the territory of the country was rejected. Serbia was also ready to transfer the case to the Hague International Tribunal or to the great powers. However, the 18 hours of the 30 minutes of this day, the Austrian envoy to Belgrade, notified the Serbian government that its response to the ultimatum was unsatisfactory, and he, along with the entire composition of the mission, leaves Belgrade. But even at this stage the possibilities for a peaceful settlement were not exhausted. However, the efforts of Sazonov to Berlin (and for some reason not to Vienna), it was reported that on July 29 (16) mobilization of four military districts would be announced. Sazonov did his best to hurt Germany, which is connected with Austria by allied obligations, as much as possible.

- And what were the alternatives? - some will ask. After all, it was impossible to leave Serbs in need.

- That's right, you can not. But the steps that Sazonov made led precisely to the fact that Serbia, which has no sea or land connection with Russia, turned out to be alone with the furious Austria-Hungary. The mobilization of the four districts Serbia could not help. Moreover, the notice of its beginning made Austria’s steps even more decisive. It seems that Austria’s declaration of war on Serbia Sazonov wanted more than the Austrians themselves. On the contrary, in their diplomatic steps, Austria-Hungary and Germany argued that Austria does not seek territorial acquisitions in Serbia and does not threaten its integrity. Her only goal is to ensure her own peace of mind and public safety.

The German ambassador, trying to somehow even out the situation, visited Sazonov and asked if Russia would be satisfied with Austria’s promise not to violate the integrity of Serbia. Sazonov gave this written response: "If Austria, realizing that the Austro-Serbian conflict has acquired a European character, will declare its readiness to exclude from its ultimatum, paragraphs that violate the sovereign rights of Serbia, Russia undertakes to stop its military preparations." This response was tougher than the position of England and Italy, which provided for the possibility of accepting these points. This circumstance testifies that the Russian ministers at that time decided to go to war, completely disregarding the opinion of the emperor.

The generals were quick to mobilize with the greatest noise. In the morning of July 31 (18) in St. Petersburg appeared announcements printed on red paper calling for mobilization. The agitated German ambassador tried to get explanations and concessions from Sazonov. At 12 hours of the night, Pourtales visited Sazonov and handed him on behalf of his government a statement that if Russia did not begin demobilization at 12 hours of the day, the German government would issue a mobilization order.

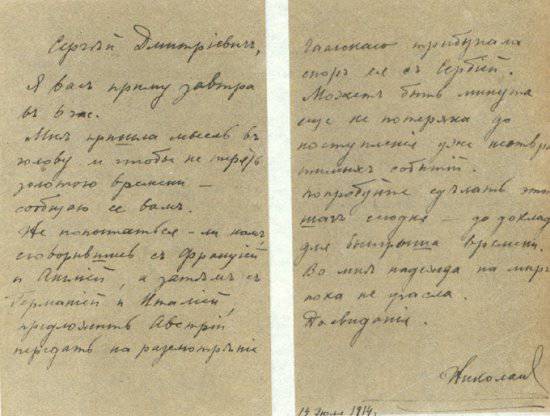

Letter of Nicholas II to Sazonov, dated July 14, 1914. The letter of the Emperor is kept in the Romanov dynasty (OPI GIM, f. 180, No. 82280)

It was necessary to cancel the mobilization, and the war would not start.

However, instead of announcing mobilization at the expiration date, as Germany would have done if she really wanted war, the German Foreign Ministry several times demanded that Pourtales seek a meeting with Sazonov. Sazonov, however, deliberately delayed a meeting with the German ambassador in order to force Germany to take the first hostile step. Finally, at the seventh hour, the Minister of Foreign Affairs arrived at the ministry building. Soon the German ambassador was already in his office. In a strong emotion, he asked whether the Russian government agreed to give an answer to yesterday's German note in a favorable tone. At that moment, it was up to Sazonov to determine whether or not to be a war. Sazonov could not know the consequences of his answer. He knew that until the full implementation of our military program, there were still three years left, while Germany completed its program in January. He knew that the war would hit foreign trade, cutting off our export routes. He also could not be unaware that the majority of Russian producers were against the war, and that the sovereign and the imperial family himself were against the war. Say it yes, and peace would continue on the planet. Russian volunteers through Bulgaria and Greece would fall into Serbia. Russia would help her with weapons. At this time, conferences would be convened which, in the end, could have extinguished the Austro-Serbian conflict, and Serbia would not have been occupied for three years. But Sazonov said his no. But it was not the end. Pertales asked again whether Russia could give Germany a favorable answer. Sazonov again firmly refused. But then it was not difficult to guess what was in the pocket of the German ambassador. If he asks the same question a second time, it is clear that in the case of a negative answer there will be something terrible. But Purtales asked this question a third time, giving Sazonov one last chance. Who is he this Sazonov, for the people, for the Duma, for the king and for the government to make such a decision? If a story and confronted him with the need to give an immediate answer, he had to remember the interests of Russia, about whether she wanted to fight, in order to work out the Anglo-French loans with the blood of Russian soldiers. Still, Sazonov repeated his “no” for the third time. After the third refusal, Pourtales removed from his pocket a note of the German embassy, which contained a declaration of war.

Information