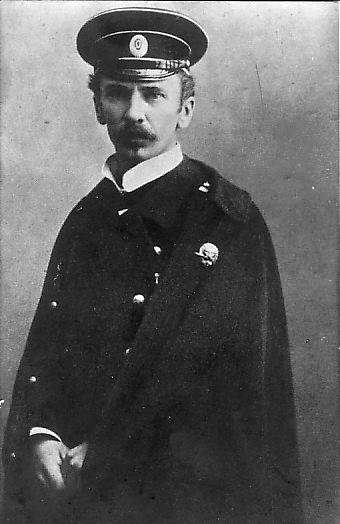

Lieutenant Schmidt

150 years ago, on February 17, 1867, a Russian naval officer, one of the leaders of the Sevastopol uprising of 1905, Petr Petrovich Schmidt was born. Peter Schmidt was the only Russian officer fleetwho joined the revolution of 1905-1907 and led a major uprising, so his name was widely known.

150 years ago, on February 17, 1867, a Russian naval officer, one of the leaders of the Sevastopol uprising of 1905, Petr Petrovich Schmidt was born. Peter Schmidt was the only Russian officer fleetwho joined the revolution of 1905-1907 and led a major uprising, so his name was widely known. Petr Petrovich, who is now mostly remembered in connection with the "sons of Lieutenant Schmidt" from the Golden Calf, lived a short, but very dramatic, life full of contradictions. Born 5 (17) February 1867, in the city of Odessa, Odessa district, Kherson province, in a noble family. His father, Petr Petrovich Schmidt, was a hereditary naval officer, a participant in the Crimean War, a hero of the defense of Sevastopol, later a rear admiral, the governor of Berdyansk and the head of the Berdyansk port. Mother Schmidt - Ekaterina Yakovlevna Schmidt, nee von Wagner. Uncle, also a hero of the defense of Sevastopol, Vladimir Petrovich, had the rank of admiral and was the senior flagship of the Baltic Fleet. It was the uncle (at the time of the death of his father, Petr Petrovich Schmidt Jr., who was only 22), he became the chief career assistant to the young officer.

Peter Schmidt Jr., from childhood, dreamed of the sea and, to the delight of the family, in 1880, he entered the St. Petersburg Naval School (Naval Cadet Corps). After graduating from the Maritime School in 1886, he was promoted to a midshipman exam and assigned to the Baltic Fleet. The young man was distinguished by great abilities in his studies, he sang well, played music and drew. But along with good qualities, everyone noted his increased nervousness and excitability. The bosses on the oddities of the cadet, and then the midshipman Schmidt turned a blind eye, believing that in time everything will come about by itself: the harsh life of the ship service will do its work.

However, the young officer surprised everyone. Already in the 1888 year, two years after the production of officers, he married and retired "due to illness" in the rank of lieutenant. He was undergoing treatment at a private hospital for nerve and mental patients in Moscow. Schmidt's wife, to put it mildly, stood out from the crowd. The daughter of a tradesman, Dominicia Pavlová, was a professional prostitute and had a yellow ticket instead of a passport. It is believed that Schmidt wanted her to "morally rehabilitate", but in general, their family life did not work out. The wife considered all his teachings to be stupid, did not bet a penny and openly cheated. In addition, in the future, Petr Petrovich had to deal with the management and upbringing of his son Yevgeny, since Dominicia was indifferent to domestic duties. The father did not accept this marriage, broke off relations with his son and soon died. In general, this case of shock for Peter the Great had no consequences for the society of that time, but there was no reaction from the command of the fleet. They did not even demand an explanation from him, because behind midshipman Schmidt, the figure of his uncle, Vladimir Schmidt, the senior flagship of the Baltic Fleet, rose from a mighty cliff.

Interestingly, during the resignation of Peter Schmidt lived in Paris, where he seriously became interested in aeronautics. He purchased all the necessary equipment and intended to professionally deal with flights in Russia. But, having returned to Russia for demonstration performances, a retired lieutenant suffered an accident on his own balloon. As a result, the rest of his life, he suffered from kidney disease caused by a hard blow of a balloon on the ground.

In the 1892 year, Schmidt appeals to the highest name "for enrollment in the naval service" and returns to the fleet with the same rank of midshipman with enrollment in the 18 th naval crew as an officer of the watch for the Rurik 1 cruiser. Two years later, he was transferred to the Far East, to the Siberian Flotilla (the future Pacific Fleet). Here he serves until 1898 on the Yanchikha destroyer, the Admiral Kornilov cruiser, the Aleut transport, the Strongman and the Gornostay and Beaver gunboats. However, soon the disease again reminded of itself. He was aggravated with a nervous illness that overtook Peter during the trip abroad. He ended up in the navy hospital of the Japanese port of Nagasaki, where he was examined by a council of doctors of the squadron. On the recommendation of the consultation Schmidt was written off to the reserve. 31-year-old lieutenant is credited to the reserve and goes to serve in the commercial (or as they said - on the "commercial") court.

During the six years of sailing on the merchant navy ships, Peter managed to serve as an assistant captain and captain on the steamers Olga, Kostroma, Igor, Saint Nikolay, and Diana. With the beginning of the Russian-Japanese war, the lieutenant was called up for active service and sent to the disposal of the headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet. Petr Petrovich was sent to the Baltic and appointed the Irtysh as a senior officer of the huge for that time transport with a displacement of 15 thousand tons. The ship was intended to supply the 2-th Pacific squadron of Admiral Rozhestvensky with the necessary materials and supplies. Peter went by transport only to the Egyptian port of Suez, where he was written off ashore due to an exacerbation of kidney disease. "Irtysh" in the course of the Tsushima battle got one big hole in the nose, not counting other less serious injuries, and sank.

The next few months, Schmidt spent in the Black Sea Fleet, commanding the destroyer number XXUMX, which stood in Izmail. In October 253, he, unexpectedly for his friends and acquaintances, took part in a political demonstration in Sevastopol, after which he was arrested. In the course of the investigation that followed, the embezzlement of treasury money from the destroyer and the neglect of service became clear. In November, Schmidt was dismissed from service. Many naval officers were sure that the former destroyer commander, No. XXUMX, was able to avoid the trial solely thanks to the eternal protection of his uncle, the admiral.

Thus, in the fall of 1905, Petr Petrovich turned out to be without certain occupations and special perspectives in Sevastopol. Schmidt was not in any party. He avoided herding at all, as he considered himself a unique person. But when a bougain began in Sevastopol, he, embittered with “injustices”, joined the opposition and became very active. Being a good orator, Petr Petrovich, participating in anti-government meetings, spoke so sharply and energetically that he quickly became a famous person. These speeches and his time in the guardhouse created him a reputation as a revolutionary and sufferer.

In November, during the revolution that swept over Russia, a strong ferment began in Sevastopol ("Sevastopol fire"). November 24 1905 year of excitement turned into a rebellion. On the night of November 26, the rebels with Schmidt arrived at the Ochakov cruiser and called on the sailors to join the uprising. "Ochakov" was the newest cruiser and for a long time stood on the "fine-tuning" in the factory. The team gathered from various crews, closely communicating with the workers and the agitators of the revolutionary parties that were among them, proved to be thoroughly propagandized, and among the sailors were their informal leaders, who actually acted as instigators of insubordination. This sailor elite - a few conductors and senior sailors - understood that they could not do without an officer, and therefore recognized the primacy of an unexpectedly declared and determined-minded revolutionary leader. The sailors under the leadership of the Bolsheviks A. Gladkov and N. Antonenko seized the cruiser in their hands. The officers who were trying to disarm the ship were driven ashore. Schmidt was in his head, declaring himself the commander of the Black Sea Fleet.

He had grandiose plans. According to Schmidt, the seizure of Sevastopol with its arsenals and warehouses is only the first step, after which it was necessary to go to Perekop and place artillery batteries there, block the road to the Crimea and thereby separate the peninsula from Russia. Further, he intended to move the entire fleet to Odessa, land the troops and take power in Odessa, Nikolaev and Kherson. As a result, the “South Russian Socialist Republic” was created, at the head of which Schmidt saw himself.

The forces of the rebels externally were large: 14 ships and vessels, and about 4,5 thousand sailors and soldiers on ships and shore. However, their combat power was insignificant, since most of the ship's guns were rendered unusable even before the uprising. Only on the Ochakov cruiser and on the destroyers artillery was in good repair. The soldiers on the shore were poorly armed, there were not enough machine guns, rifles and cartridges. The rebels missed a favorable moment for the development of success, the initiative. The passivity of the rebels prevented us from attracting the entire Black Sea squadron and the Sevastopol garrison. Schmidt sent a telegram to Tsar Nicholas II: “The glorious Black Sea Fleet, sacredly loyal to its people, demands from you, sir, the immediate convocation of the Constituent Assembly and will not obey your ministers. Fleet Commander P. Schmidt ".

However, the authorities have not yet lost their will and determination, as in 1917 year. Commander of the Odessa Military District, General A. V. Kaulbars, Commander of the Black Sea Fleet, Vice Admiral G. P. Chukhnin and Commander of the 7 Artillery Corps, Lieutenant-General A. N. Meller-Zakomelsky, appointed by the king at the head of a punitive expedition, pulled down to 10 Thousands of soldiers and were able to put the 22 ship with 6 Thousands of people crew. The rebels were given an ultimatum to surrender. Having received no response to the ultimatum, the troops loyal to the government went on the offensive and opened fire on the “internal enemies”. An order was issued to open fire on rebellious ships and vessels. Not only ships, but also coastal artillery, guns of land forces, as well as soldiers from machine guns and rifles from the shore, fired. As a result, the insurgency suppressed. Wounded Schmidt with a group of sailors tried on the destroyer number 270 to break into the Artillery Bay. But the ship was damaged, lost its course, and Schmidt and his comrades were arrested. At trial, Schmidt tried to mitigate the punishment of others, took all the blame on himself, expressed full readiness to be executed.

In general, given the scale of the rebellion and its danger to the empire, when there was a possibility of an uprising in a significant part of the Black Sea Fleet, with the support of part of the ground forces, the punishment was quite humane. But the uprising itself was crushed firmly and resolutely. Hundreds of sailors died. The leaders of the Sevastopol Uprising, P. P. Schmidt, S. P. Chastnik, N. G. Antonenko, and A. I. Gladkov, were sentenced by a naval court in March 1906 to be shot on the island of Berezan. Over 300 people were sentenced to different terms of imprisonment and hard labor. About a thousand people were subject to disciplinary punishment without any trial.

It is worth noting that in the Russian Imperial Navy there was a strict ban on political activity. Moreover, the “taboo” was more informal, but it was strictly observed. Even those naval officers who were considered liberals in the navy, the unwritten rules, for the most part, did not violate. Vice-Admiral Stepan Makarov always said directly that the army and navy should be out of politics. The business of the armed forces is to guard their homeland, which must be protected regardless of the form of the existing system.

Schmidt has become a rare exception. It is possible that the reason for the naval officer’s abrupt transition to the side of revolutionaries is the psychic instability of Peter. In the Soviet historiography, taking into account the popularization of this character, this question was bypassed. Petr Petrovich was a man easily excitable, he had previously been treated in a hospital “for the nervous and mentally ill”. His illness was expressed in unexpected bouts of irritability, turning into a rage, followed by hysteria with convulsions and rolling on the floor.

According to midshipman Harold Graf, who served Peter on the Irtysh for several months, his senior officer "came from a good noble family, knew how to speak beautifully, played the cello superbly, but was also a dreamer and visionary." Nor can it be said that Schmidt also came under the category of “sailor friends”. “I myself saw him several times, brought out of patience by the lack of discipline and rude answers of the sailors, beat them right there. In general, Schmidt never fawned on the team and treated it the same way as other officers treated it, but always tried to be fair, ”noted Graf. According to the naval officer: “Knowing Schmidt well in terms of joint service, I am convinced that if his plan succeeded in 1905 and triumph in all of Russia, the revolution ... he would be the first to be terrified of what he had done and would become a sworn enemy of Bolshevism.”

Meanwhile, the revolutionary events in the Russian empire continued to boil, and very soon after the lieutenant’s execution at rallies of various parties, young people began to appear who, calling themselves “the son of Lieutenant Schmidt”, on behalf of the father who had died for his freedom called for revenge, fight the tsarist regime or render feasible material assistance to revolutionaries. Under the "son of the lieutenant" acted not only revolutionaries, but simply speculators. As a result, "sons" divorced completely indecent amount. Moreover, even the "daughters of Schmidt" appeared! For some time the “children of the lieutenant” flourished completely, but then, with the decline of the revolutionary movement, Lieutenant Schmidt was almost forgotten.

In Soviet times, the “lieutenant’s children” were revived in the second half of the 1920s. In 1925, the twentieth anniversary of the first Russian revolution was celebrated. In preparing the holiday, the party's veterans, to their considerable surprise and chagrin, found that the majority of the country's population did not at all remember or did not know the heroes who died during the first revolution. The party press began an active information campaign, and the names of some revolutionaries were hastily extracted from the darkness of oblivion. A lot of articles and memoirs were written about them, monuments were established for them, streets, embankments, etc. were named after them. Peter Petrovich Schmidt became one of the most famous heroes of the first revolution. True, propagandists hurried somewhat and in a hurry missed some unfavorable facts for the hero. Thus, prominent royal admirals turned out to be relatives of the revolutionary, and his son Yevgeny participated in the Civil War on the side of the White movement and died in emigration.

Information