Another truth

The most famous of the gendarmes of Russia was the eldest of the four children of the infantry general, the Riga civil governor in 1796 — 1799, Christopher Ivanovich Benkendorf and baroness Anna-Juliana Schelling von Kanstadt. His grandfather, Johann-Michael Benkendorf, in Russian, Ivan Ivanovich, was a lieutenant-general and chief commander of Revel. With him, who died in the rank of lieutenant-general, is associated the approach of Benkendorf to the Russian throne. Catherine II, after the death of Ivan Ivanovich in memory of the 25-year-old “immaculate service in the Russian army,” made his widow, Sofya Ivanovna, nee Levenshtern, educator of the great princes Alexander and Konstantin Pavlovich. In this role, she remained incomplete four years, but this period was enough to play a large role in the fate and career of future grandchildren.

Alexander was born 23 June 1783 of the year. (It is believed that this date may also vary within 1781 and 1784. - Note. Aut.) Thanks to the palace connections of the grandmother and mother, who came to Russia from Denmark in the suite of the future Empress Maria Feodorovna, his career was arranged immediately. In 15 years, the young man was enlisted as a non-commissioned officer in the privileged Life Guards Semenov regiment. Its production as a lieutenant also followed very quickly. And it was precisely in this rank that he became the aide-de-camp of Paul I. Moreover, unlike many of his predecessors, who had suffered a lot from the unpredictable emperor, the young Benkendorf did not know such problems.

Although, I must say, the favorable prospects associated with the honorary position of aide-de-camp did not deceive him. At the risk of causing supreme displeasure, he asked for the Caucasus in 1803, and it did not even remotely resembled diplomatic trips to Germany, Greece and the Mediterranean, where the emperor sent young Benkendorf.

The Caucasus, with its exhausting and bloody war against the mountaineers, was a real test of personal courage and ability to lead people. Benkendorf passed it with dignity. For equestrian attack during the storming of the Ganji fortress, he was awarded the Orders of St. Anne and St. Vladimir of the IV degree. In the 1805 year, along with the "flying squad" of the Cossacks, whom he commanded, Benkendorf defeated the advanced enemy posts at the Gamlu fortress.

Caucasian battles were replaced by European. In the Prussian campaign of 1806 — 1807 for the battle of Preussisch-Eylau, he was promoted to captain and then to colonel. This was followed by the Russian-Turkish wars under the command of ataman M.I. Platov, the hardest battles in crossing the Danube, the capture of Silistra. In 1811, Benkendorf at the head of two regiments made a desperate sortie from the Fortress of Lovchi to the fortress of Ruschuk through enemy territory. This breakthrough brings him "George" IV degree.

In the first weeks of the Napoleonic invasion, Benckendorf commanded the vanguard of the detachment of Baron Vincengorod, on July 27, under his leadership, the detachment made a brilliant attack in the case of Velizh. After being liberated from the enemy of Moscow, Benkendorf was appointed commandant of the ravaged capital. During the period of the persecution of the Napoleonic army, he distinguished himself in many cases, capturing three generals and more 6 000 Napoleonic soldiers. In the 1813 campaign, becoming the head of the so-called "flying" squads, first defeated the French at Tempelberg, for which he was awarded "George" III degree, then forced the enemy to surrender Furstenwald. Soon he was with the detachment in Berlin. For the unparalleled courage shown during the three-day cover for the passage of the Russian troops to Dessau and Roskau, he was awarded a golden saber with diamonds.

Then there was a swift raid on Holland and a complete defeat of the enemy there, then Belgium - his detachment took the cities of Louvain and Mecheln, where the French had 24 guns and 600 British prisoners repulsed. Then, in 1814, there was Lutthich, the battle of Red, where he commanded the entire cavalry of Count Vorontsov. Awards followed one after the other - in addition to “George” of the III and IV degrees, another “Anna” of the I degree, “Vladimir”, and several foreign orders. He had three swords for bravery. He ended the war in the rank of Major General.

In March 1819, Benkendorf was appointed Chief of Staff of the Guard Corps.

The seemingly flawless reputation of a warrior for the Fatherland, which placed Alexander Khristoforovich among the most prominent commanders, did not bring him, however, that glory among fellow citizens, which accompanied the people who had passed the crucible of the Patriotic War. Benkendorf did not manage to be like heroes either in life or after death. His portrait in the famous gallery of 1812 heroes of the year is undoubtedly surprised by many. But he was a brave soldier and an excellent commander. Although in stories many human lives in which one half of life cancels the other. Benkendorf's life is a vivid example.

How did it all start? The formal reason for colleagues to look at Benkendorf from a different angle was the clash with the commander of the Preobrazhensky regiment KK Kirch. Concerned about the interest shown by the Guards youth in the revolutionary events taking place in Spain, Benkendorf ordered Kirch to prepare a detailed memo on “dangerous conversations”. He refused, saying he did not want to be a scammer. The chief of the Guards headquarters in anger put him out the door. The officers of the Preobrazhensky regiment learned about the incident, of course, with might and main rejecting Benkendorf’s initiative. Justification for this act simply could not be, moreover, that informing was not in honor, the main thing was that the spirit of free-thinking, brought from foreign campaigns, literally wailed among people in uniforms, and even more than among civilians.

A few months passed, and the so-called “Semyonovskaya Story” broke out. Cruelty to his subordinates F.E. Schwartz, the commander of the regiment for Benkendorf, outraged not only the soldiers, but also the officers. The uprising of the Life Guards Semenov regiment lasted only two days - from 16 to 18 of October 1820 of the year, but this was enough to bury the government’s confidence in the absolute loyalty not only of the guards, but also of most army people.

Emperor Alexander I

Benkendorf was one of the first to understand what the “fermentation of minds” could lead to, those arguments, disputes and plans that matured at the heart of close officer meetings. In September, 1821, on the table of Emperor Alexander I, was laid a note about secret societies that exist in Russia, and in particular about the “Union of Welfare”. She had an analytical character: the author considered the reasons that accompanied the emergence of secret societies, their tasks and goals. It also expressed the idea of the need to create in the state a special body that could keep the mood of public opinion under surveillance, and if necessary, stop the illegal activities. But among other things, the author named by her those names in whose minds the spirit of free-thinking settled. And this circumstance made a note with a denunciation.

The sincere desire to prevent a breakdown in the existing state order and the hope that Alexander would get a sense of what was written were not justified. It is well-known that Alexander said about the participants of secret societies: “It’s not for me to judge them.” It looked noble: the emperor himself, was the case, free-thinking, plotting extremely bold reforms.

But the act Benkendorf just was far from nobility. 1 December 1821, an irritated emperor, removed Benkendorf from command of the Guards headquarters, appointing him commander of the Guards Cuirassier Division. It was a clear disfavor. Benkendorf, in vain attempts to understand what caused it, wrote again to Alexander. He could hardly have guessed that the emperor was jarred on this paper and he taught him a lesson. And yet the paper lay under the cloth without a single mark of the king. Benkendorf calmed down ...

“The enraged waves raged on the Palace Square, which was one huge lake with Neva, which poured out on Nevsky Prospect,” so wrote an eyewitness to the terrible November night of 1824. Water in some places in St. Petersburg then rose to 13 feet and 7 inches (that is, more than four meters). The city, turned into a huge lake agitated, floated carriages, books, police booths, cradles with babies and coffins with the dead from blurred graves.

Natural disasters have always found and scoundrels, in a hurry to take advantage of someone else's misfortune, and the desperate brave men who saved others, not caring about themselves.

So, having crossed the embankment, when the water reached him already on the shoulders, General Benkendorf reached the boat, on which the midshipman of the Guards crew, Belyaev, was. Before 3 hours of the night together they managed to save a huge number of people. Alexander I, who received many testimonies of Benkendorf’s courageous behavior in those days, awarded him a diamond snuffbox.

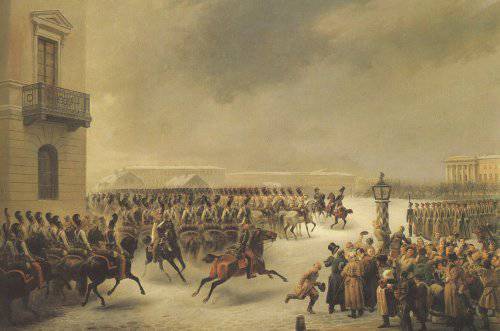

A few months passed, and the emperor was gone. And on December 14, St. Petersburg's 1925 exploded with the Senate Square. The fact that in the end it became perhaps the most sublime and romantic page of Russian history didn’t seem so to witnesses of that memorable December day. Eyewitnesses are writing about a city numb with horror, about direct fire volleys into the dense ranks of the rebels, about those who fell dead face down in the snow, about streams of blood flowing on the Neva ice. Then - about the uptight soldiers, the officers who were hanged and exiled to the mines. Some people regretted that, they say, “they are terribly far from the people,” and therefore the scales were not the same. And then, you see, it’s burning: a brother against a brother, a regiment to a regiment ... Benkendorf, it seemed that there was a clear overbearing promise and a terrible loss to the state even in the fact that an excellent man, midshipman Belyaev, with whom they raged on that crazy night as if by sea, all over Petersburg, 15 is now rotting in Siberian mines for years.

But precisely those tragic days marked the beginning of the trust and even friendly affection of the new emperor Nicholas I and Benkendorf. There is evidence that in the morning of December 14, having learned about the rebellion, Nikolai told Alexander Khristoforovich: "Tonight, maybe both of us will not be in the world anymore, but at least we will die, having fulfilled our duty."

Benkendorf saw his duty in protecting the autocrat, and therefore the state. On the day of the rebellion, he commanded the government forces located on Vasilyevsky Island. Then he was a member of the Investigation Commission in the case of the Decembrists. Sitting in the Supreme Criminal Court, he repeatedly appealed to the emperor with requests to mitigate the fate of the conspirators, while knowing well how much any mention of criminals was received by Nikolay.

The brutal lesson taught to the emperor of December 14, was not in vain. By the will of fate, that same day changed the fate of Benkendorf.

In contrast to the royal brother, Nicholas I carefully got acquainted with the age-old "note" and found it very efficient. After the massacre of the Decembrists, which cost him a lot of black minutes, the young emperor in every way sought to eliminate possible repetitions of the similar in the future. And I must say, not in vain. A contemporary of those events N.S. Schukin wrote about the atmosphere prevailing in Russian society after December 14: “The general mood of minds was against the government, and the sovereign was not spared. Young people sang songs of abuse, copied outrageous poems, scolding the government was considered a fashionable conversation. Some preached the constitution, others a republic ... "

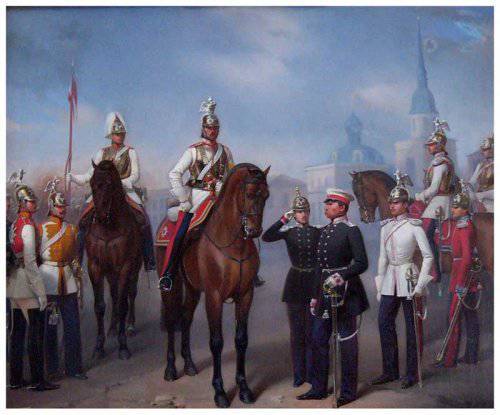

Benkendorf's project was, in fact, a program for creating a political police in Russia. What was to be done? Engage in political investigation, extracting the necessary information, suppressing the activities of those who opposed the regime. When the question was resolved what exactly the political commission would be engaged in, another arose - who would be engaged in investigation, gathering information and curbing illegal actions. Benkendorf responded to the king - gendarmes.

In January, 1826, Benkendorf presented to Nicholas the “Project on the High Police Device”, in which, by the way, he also wrote about what qualities her boss should possess and on the need for his unconditional unity of command.

“In order for the police to be good and embrace all the points of the Empire, it is necessary that it obey the strict centralization system, be feared and respected, and respect it be inspired by the moral qualities of its superior ...”

Alexander Khristoforovich explained why it is useful for society to have such an institution: “Villains, schemers and narrow-minded people, repenting of their mistakes or trying to atone for their guilt by denunciation, will at least know where to turn to them.”

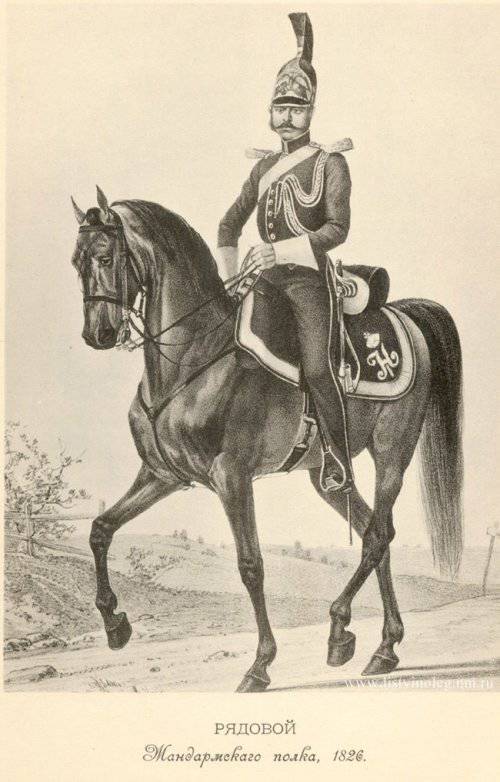

In 1826, more than 4 thousand people served in the corps of gendarmes. Nobody was driven here by force, on the contrary, there were far fewer vacancies than those who wanted to: the soldiers were selected only competent, the officers were accepted only with good recommendation. However, some doubts about changing the army uniform to gendarme still overwhelmed. How will their duties be combined with the notion of honor of a nobleman and an officer?

By the way, the well-known L.V. Dubbelt, who later made a very successful career in the gendarmes corps. Despite the fact that he, being in retirement “without a place”, lived almost starvingly, the decision to put on a blue uniform was not easy for him. He consulted with his wife for a long time, shared with her doubts about the correctness of his choice: “If I, joining the gendarmes corps, become a scammer, an earphone, then my good name, of course, will be tainted. But if, on the contrary, I ... will be the support of the poor, the protection of the unfortunate; if I, acting openly, will force to give justice to the oppressed, I will observe that in court places they give heavy business a direct and fair direction - then what will you call me? .. Should I not assume fundamentally that Benkendorf himself is a virtuous and noble person will not give me instructions that are not peculiar to an honest man? "

Soon came the first conclusions and even generalizations. Benkendorf points to the emperor at the true autocrats of the Russian state - at the bureaucrats. “Plunders, meanness, misinterpretation of laws are their craft,” he tells Nikolay. “Unfortunately, they rule ...”

Benkendorf and his closest assistant M.Ya. Fok considered: “To suppress the intrigues of the bureaucracy is the most important task of the Third Division”. I wonder if they were aware of the utter doom of this struggle? Probably yes. Here, for example, Benkendorf reports that a certain official of special assignments “gained a great advantage” by fraud. How to deal with him? The emperor replies: "I do not intend to accept dishonest people in the service." And no more than that ...

It is necessary to say that Benkendorf was not only informing, he sought to analyze the actions of the government, to understand what causes public irritation. In his opinion, the revolt of the Decembrists was the result of the “deceived expectations” of the people. And therefore, he believed, public opinion must be respected, "it cannot be imposed, it must be followed ... You cannot put him in jail, but by pressing you can only bring it to bitterness."

In 1838, the head of the Third Division points out the need to build a railway between Moscow and St. Petersburg, in 1841, he notes major health problems, in 1842 he warns about general dissatisfaction with the high customs tariff, and in the same series “grumble about recruiting sets.

1828 year was the time of the approval of the new censorship charter. Now the literary world, formally remaining under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of National Education, was transferred to the competence of the Third Division.

Censors were recruited, and at the same time people are very noticeable. Among them, F.I. Tyutchev, S.T. Aksakov, P.A. Vyazemsky. What did Mr. Benkendorf impose on them? They had to ensure that the persons of the imperial family were not discussed in the press and that the authors avoid such an interpretation of events that could “involve the state in the abyss of misfortunes”.

It must be said that the biggest troubles awaited the chief of gendarmes precisely at the moments of contact with the intellectual elite. Everyone was dissatisfied with them: both those who controlled them and those who were under control.

Pushkin was reassured by irritated Vyazemsky, who wrote the epigrams on Benkendorf: “But since in essence this honest and worthy man, too careless to be vindictive, and too noble to try to hurt you, do not allow yourself to have hostile feelings and try to talk with him frankly. " But Pushkin is extremely rarely mistaken in assessing people. His attitude to the chief of the III Division did not in the least differ from the general, such ironically benevolent.

Portrait of A. S. Pushkin, artist O. A. Kiprensky

It is known that Nicholas I volunteered to take over censorship of Pushkin's work, the genius of which, by the way, was quite conscious. For example, after reading the negative opinion of Bulgarin addressed to the poet, the emperor wrote Benkendorf: “I forgot to tell you, dear friend, that in today's issue of Northern Bee there is again an unfair and pamphlet article directed against Pushkin: therefore, I suggest you call upon Bulgarin and prohibit From now on, he will publish any criticism of Pushkin’s literary works. ”

Nevertheless, in 1826 — 1829, the Third Division actively carried out secret supervision of the poet. Benkendorf personally investigated a very unpleasant case for Pushkin “about the distribution of“ Andrei Chenier ”and“ Gabriiliad ”. The widespread use of private letters in the 30-s by Benkendorf’s practice of literally infuriating the poet. “The police prints the letters of the husband to his wife and brings them to the king (well-mannered and honest), and the king is not ashamed to confess ...”

These lines are written as if they were intended to be read by both the king and Benkendorf. Heavy service, however, the powerful of the world, and it is unlikely the words of a man, the exclusivity of which both recognized, slipped past, without hurting either the heart or the mind.

Alexander Khristoforovich perfectly understood all the negative aspects of his profession. It was not by chance that he wrote in his “Notes” that during a serious illness that happened to him in 1837, he was pleasantly surprised by the fact that his house “became the gathering place of the most diverse society”, and, most importantly, he emphasized independent in its position. "

“With the position I held, this was, of course, the most brilliant report for my 11-year management, and I think that I was almost the first of all the heads of the secret police, whom they feared to die ...”

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf

In general, it seems, Benkendorf never indulged in particular joy over the power he had. Apparently, both the natural mind and life experience taught him to rank it among a certain phantom.

Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benkendorf died on the ship, carrying him from Germany, where he was undergoing long-term treatment, to his homeland. He was over sixty. His wife was waiting for him in Fall, their estate near Reval (now Tallinn). The ship has already brought the dead. It was the first grave in their cozy estate, although the earl’s hands never reached the household.

In the study of the Falls castle he kept a wooden fragment, left over from the tomb of Alexander I, which was set in bronze in the form of a mausoleum. On the wall, in addition to portraits of the sovereigns, hung a famous watercolor by Coleman "Riot on Senate Square". Boulevard, generals with plumes, soldiers with white belts on dark uniforms, a monument to Peter the Great in cannon smoke ...

Something, apparently, did not let go of the count, if he kept this picture before his eyes. Probably, Alexander Khristoforovich was not a bad person at all. But the trouble is: every time you have to prove it.

Think Tank - Third compartment with 72 employees. Benkendorf picked them up meticulously, according to three basic criteria - honesty, intelligence, and good faith.

Employees of the service entrusted to Benkendorf dived into the work of ministries, departments, and committees. The assessment of the functioning of all structures was based on one condition: they should not overshadow the interests of the state. In order to provide the emperor with a clear picture of what is happening in the empire, Benkendorf, based on numerous reports from his staff, compiled an annual analytical report, likening it to a topographic map warning where the swamp is, and where there is a chasm.

With his inherent scrupulousness, Alexander Khristoforovich divided Russia into 8 state districts. In each - from 8 to 11 provinces. Each district has its own gendarme general. In each province - by gendarme branch. And all these threads converged in a building of ocher color on the corner of the Moika and Gorokhovaya embankments, at the headquarters of the Third Division.

The corps of gendarmes was conceived as an elite, providing for substantial material support. In July, 1826, the Third Branch was created - an institution designed to carry out secret supervision of society, and Benkendorf was appointed its head. In April, 1827, the emperor signed a decree on the organization of a gendarme corps with the rights of the army. Benkendorf became his commander.

In his own way, the chief of the III Division was in kind highly integral. Realizing once the principles of his service to the Fatherland, he did not change them. As literally all his life, he did not change another inclination, which seemed to have bathed him in both harsh military and ambiguous police craft.

“... I met Alexander Benkendorf,” wrote Nikolay's wife, Alexandra Fedorovna, in 1819. “I heard a lot about him during the war, while still in Berlin and Dobberen; all praised his courage and regretted his careless life, at the same time laughing at her. I was struck by his power-like appearance, which was not at all inherent in the reputation of the rake established behind him. ”

Yes, Count Benkendorf was extremely in love and had a lot of novels, each other more fascinating and - alas! - more quickly. Let us repeat after the now forgotten poet Myatlev: “We’ve heard nothing but just say ...” About the famous actress, M. Georges, the subject of Napoleon’s passion (at one time), it was said that her appearance in St. Petersburg with 1808 1812 year was associated not so much with the tour, but with the search for Mr. Benkendorf, who promised to marry her. But why not promise in Paris!

As befits a classic ladies' man, Alexander Khristoforovich hastily married 37's year of life. I was sitting in a house. They ask him: “Will you have Elizaveta Andreevna in the evening?” - “What kind of Elizabeth Andreevna?” Astonished people see. "Oh yes! Well, of course, I will! ”In the evening, he is at the address requested. The guests are already sitting on the sofas. This and that. The living room includes the hostess Elizaveta Andreevna, the widow of General PG Bibikova. Here at once his fate and decided ...

Information