Sea rivalry of England and Holland. The Battle of Lowestoft

In nature, a predator has its own territory in which it lives, hunts and which it protects from other predators. In humans, the line between rational sufficiency and non-viable needs often becomes very conditional. British and Dutch East India companies were the most real predators, states in the state, living by their own rules and not recognizing the rules of others. Their trade interests extended to almost the entire world explored by the beginning of the seventeenth century. But, by the way, even in that enormous world for the imagination and consciousness of yesterday’s inhabitants of the Middle Ages, these two predators with polite smiles and gentlemen’s courtesy already had little space. When it did not remain at all, irreconcilable contradictions led England and Holland to a whole series of wars in the second half of the XVII century.

How two neighbors decided to do big business

Britain’s path to the unofficial but very caressing pride of the title “Lady of the Seas” was long and thorny. At first, it was a long and persistent struggle against the Spanish Hidalgo, whose galleons were packed with gold and plied the seas and oceans. And the maritime traditions of stubborn islanders were born under the creak of the Golden Fallow deer masts and in the clouds of smoke Gravelina. The Spanish Empire slowly, gradually, lost ground. However, England was already a little simple piracy. Well-established trade, based on a network of forts and strongholds, could bring large and, most importantly, stable incomes into the treasury forever gaping with its hungry mouth.

The British approached the case on a large scale, as such were their material claims. The East East India Company was founded in 1600. She received a monopoly on trade with all countries of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The company's activities were regulated by a special charter, which was issued for a certain temporary period. Then the actions of the charter were extended, amendments and additions were made to it. The company was led by a board of directors and a meeting of shareholders. Subsequently, the management acquired various committees that were responsible for the industry. Already in the first quarter of the seventeenth century, the East India Company owned numerous trading trading stations in Indonesia. In 20's the same century begins the active penetration of the British in India. From there, a large assortment of scarce colonial goods was exported, which was purchased from the Indians for silver and gold. The nuance was that even in the time of Queen Elizabeth I, the export of gold and silver coins from England was prohibited. However, the East India Company repeatedly passed through parliament permits for certain expenditures of this “strategic resource” and, thanks to the cheapness of Indian goods, received huge profits.

The main rivals of the British were still not the Spaniards, increasingly weakening on the seas, but close neighbors. On the opposite bank of the Channel were proclaimed themselves in 1581, the Netherlands independent of the crown of the Habsburgs. Experienced sailors, courageous and enterprising people, the Dutch knew how to benefit from the advantageous location of their country. 9 On April 1609, a truce was signed between Spain and its rebellious provinces. However, the Netherlands will become a fully recognized independent state only in 1648. In a short period, the country became one of the largest trade centers of Western Europe - the rivers flowing through the territory of the Netherlands allowed to transport goods from the Dutch ports into the mainland.

The Dutch East India Company, an analogue and direct competitor of the British, was founded in 1602. She was granted an 21-year monopoly on trade with overseas countries. In addition, the company was allowed to wage wars, enter into diplomatic treaties, conduct its own policies in the colonies. She received all the necessary power attributes: fleet, army, police. In fact, it was a state in a state, a prototype of modern transnational corporations. She was governed by a council from 17 of the most influential and wealthy merchants, whose authority included determining the company's internal and external policies. The Dutch expansion was dynamic and vigorous: with 1605, the subjection of the rich to trade-friendly resources of the Moluccas began, in Batumi, in 1619 in Indonesia, Batavia is founded, actually the future center of local colonial possessions. In 1641, Malacca was taken under control, and in 1656, the island of Ceylon. In 1651, Kapstad is based on the Cape of Good Hope. Under the control of the Dutch are many of the key points on a long journey from Asia to Europe.

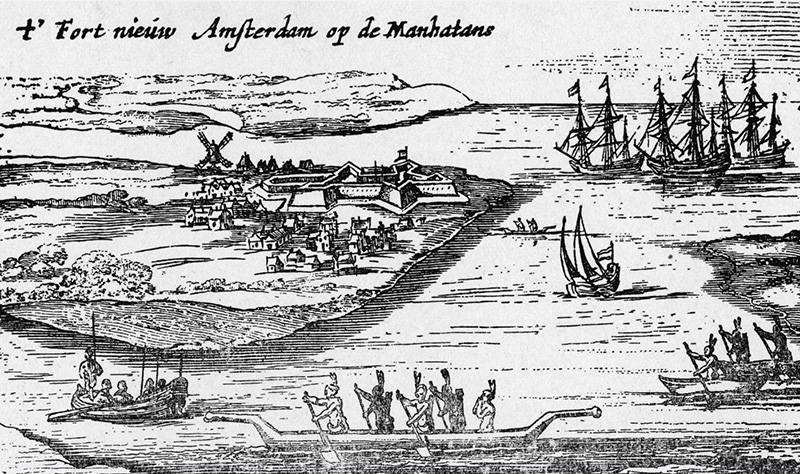

Not spared their business and practical attention and America. In 1614, a fort was founded on Manhattan Island, and later the city - New Amsterdam. By the middle of the XVII century. for a very short time, more recently, the provincial Netherlands has emerged as one of the leading colonial powers. Revenues from trade were, to put it mildly, weighty - spices, silk, cotton fabrics, coffee sold at artificially inflated prices. The rates of profit from the same spices reached the colossal marks in 700 – 1000%. In 1610, Chinese tea was first imported to the Netherlands, and its sales soon became one of the main sources of wealth.

The Amsterdam Stock Exchange was the largest in Europe, and by the middle of the XVII century the Dutch fleet had almost 20 thousand ships. Fishing was booming, whaling was organized off the shores of the Arctic Spitsbergen, the abundance of imported raw materials stimulated the development of the manufacturing industry and manufactory. And the welfare of the rosy inhabitants of the United Provinces would continue to multiply, if not for one small, but very annoying circumstance. On the other hand, the English Channel was no less enterprising, adventurous, and, moreover, militant gentlemen, who were also burdened with thoughts of filling their considerable size of chests. And sooner or later, their roads should have crossed, and not at a good hour.

Storm over the island

Life on the island, located opposite the vast Dutch harbors, also tensely throbbed. 1 June 1642. Parliament submitted to King Charles I his famous “19 points”, the essence of which was to limit royal power and expand the powers of parliament. The puritan merchants who sounded in breadth and the masters of the manufactures who joined them insistently demanded their proper place in the sun. The aristocracy that kept itself up in raids and wars, but the aristocracy that had carefully preserved its own arrogance, naturally did not want this in any way. The conflict was inevitable, and 22 August 1642, the king raised his standard in Nottingham. Thus began a civil war, which, like all similar wars, was distinguished by its marked cruelty and the complete absence of compromises and dialogues. It lasted for nearly five years, until in February 1647, the king who had taken refuge in Scotland was kindly given out to opponents for modest 200 thousand pounds.

30 January 1649. Charles I finally lost not only the crown, but also the part of the body provided for her to wear. However, peace and tranquility did not return to England. Having dispersed the corners of the royalists and their sympathizers, Oliver Cromwell, the recent zealous fighter with absolutism, concentrated in his hands the almost sole power. And soon he began just as earnestly, with Puritan ferocity, to fight with everything that seemed to him objectionable. The Irish were disagreeable with Catholicism, according to Cromwell, Catholicism, and in August 1649, the parliamentary army landed on Green Island and three years later took it under full control, not particularly ceremonial with the local population. Then, in 1650, British troops invaded Scotland, defeating supporters of Charles I, Charles II, a seeker of revenge, at Dunbar. In honor of this victory, a commemorative medal was struck, emphasizing the importance of the event. The next such regalia will be minted only after more than a century and a half - to commemorate the battle of Waterloo.

During the civil war in England, the Netherlands formally maintained neutrality, making full use of this vantage point to improve its trading and economic position in the world. In the United Provinces many aristocrats who had escaped from England found shelter, the son of the executed King Charles II and his mother Henrietta Maria the French immediately settled. Of course, discontent with such an ambiguous position was ripening in England itself, and the Netherlands itself soon began to be perceived as a stronghold of the shortage of contra.

At the same time prudent Cromwell was in no hurry to quarrel with such a profitable neighbor. In order to disentangle the whole tangle of accumulated contradictions, an embassy led by Isaac Dorislaus, a former prosecutor of the parliamentary army, who was born and lived in the Netherlands for a long time, was sent to Holland. It was he who, as a connoisseur of local undercurrents, had to probe the ground for a possible union between the two countries, where England tactfully kept the leading place for herself. When the ambassador arrived in The Hague, a bloody incident occurred. 11 May 1649 Mr. Dorislaus dined in one of the inns. A group of “activists” burst in there, out of modesty, wearing masks and armed with swords for persuasiveness. Accompanying their actions with shouts of revenge for the execution of Charles I, they simply killed the English ambassador. The Dutch side let everything go down because it was supposed that one of the “activists” was the son of the executed king, and the royalists enjoyed considerable support from the local nobility.

However, Cromwell did not back down - the idea of an alliance of Protestant states, England, the Netherlands and Sweden, under the undoubted leadership of the first, greatly fascinated him. In such a composition, it was possible to measure strength even with the omnipotent Habsburgs. The British leader sends a new embassy - already led by Chief Justice St. John. Not distinguished by excessive diplomatic tact, the new ambassador laid out London's proposals in such a way that the Dutch, hard-working merchants, experts in seeking profit and just business people, immediately recorded all their English tricks with their "manager's vizier". The cunning wisdom of the islanders' proposal for a "close alliance" was so obvious that it caused embarrassment, smoothly turning into indignation. Cromwell's initiative was regarded as an unceremonious attempt to force the Netherlands to pay for British foreign projects, while remaining an errand boy. Such a solid role was completely out of the hands of the respectable Amsterdam masters, and they, grumbling with displeasure, agreed, through the mouths of the General States, to formulate only a trade union, but no more. The mission of the former judge failed. However, everyone knows that, in addition to diplomatic ones, there are simpler and, in some cases, more convincing ways of implementing foreign policy plans. And both fleet were ready to contribute to these plans.

The first test of strength

By 1650, the English merchant navy was much more modest than its Dutch rival and totaled just over 5 thousand units. But with regard to the naval forces, a completely different picture could be observed. The maritime traditions established in the reign of the “queen devil” continued to live and strengthen. In the country there were actually five royal shipyards, not counting the many private ones. The British clearly understood the line between a commercial ship and a military ship. In 1610, the royal shipyard of Woolwich builds the 55-gun "Princess Royal", which has three artillery decks. Heavy guns were placed on the bottom deck, and light ones on the middle deck and on the upper deck. The initial layout of the four masts was soon recognized as redundant, and the ship became three-masted. Thus, the classic ship-class sailing equipment appeared.

In 1637, the 102-gun "Sovereign of the Siz" ("Lord of the Seas"), which is considered the first real battle ship in stories shipbuilding. The 1645 built the first full frigate - the 32-gun "Constant Warwick", which, like the Sovereign of the Seas, has three masts, but only one artillery deck. The significance of the appearance of these ships was comparable and even exceeded in scale the construction by Lord Fisher of his legendary Dreadnought. The British were the first to understand all the superiority of new types of ships over obsolete galleons, pinas and flutes. In 1651, the royal fleet already numbered the 21 battleship (then they were called 1 – 3 rank ships) and 29 frigates (4 – 6 rank ships). A number of ships were under construction, and in total, together with representatives of other classes, Royal Nevi could put out no less than 150 warships.

The situation was different for the Dutch. Their merchant fleet was without exaggeration the largest in the world and totaled almost 20 thousand ships. But the real military among them was very small. Entrepreneurial and thrifty, the Dutch tried to combine military and commercial elements in one ship. Most of the Dutch navy was converted into merchant ships with all the ensuing consequences. The ships of the United Provinces, as a rule, had a smaller draft than the English (affected by the abundance of shallow harbors), and more rounded contours because of their commercial purpose. This is not very well reflected in speed, maneuverability and, of course, weapons. By the beginning of the first Anglo-Dutch War, the Netherlands did not have any ships comparable to the Sovereign of the Seas. Only in 1645, the Dutch built the 53-cannon Brederode, which was exclusively a warship. He also became the flagship. Fleet administration was very cumbersome - the Netherlands was formally divided into 7 provinces, five of which had their own Admiralties and their own admirals. In the event of a war, the council considered the Admiralty chief of Amsterdam elected a vice admiral to command the entire fleet of the country, who then himself appointed junior flagships and senior officers. In fact, it was already an archaic system for the choice of a military leader for the 17th century.

The total number of warships of the Dutch fleet to the beginning of the first war with England did not exceed 75 units. The problem was also in the dispersion of these limited forces across different regions - the Dutch had to defend their trade in the most remote corners of the then-known world.

Returning to England, St. John, in order to justify the results of his "brilliant" mission, began at every turn to tell that, they say, the vile Dutch themselves sleep and see how to make war with the noble and meek Englishmen. These temperamental and sincere utterances lay on the long-plowed and perfectly cultivated soil. The calls to teach the “greedy merchants” to teach have already been expressed not in a whisper on the sidelines of the parliament, but from its rostrum. But the Anglo-Saxons would not have been Anglo-Saxons, if they had not tried to organize an entertaining show. It was not at all respectable to declare war only from the fact that they were not taken as allies, but it is possible to force it to do the interesting side. And Mr. Oliver Cromwell issued, and the parliament predictably approved 9 of October 1651 of the so-called Navigation Act, according to which all colonial goods could be brought into England only by British ships. The import of salted fish could be carried out only if it was caught in English waters. On foreign ships, it was allowed to import only products manufactured directly in these countries, that is, mainly agricultural products and handicraft products. Violators of the court order were confiscated.

It is believed that the publication of the Navigation Act was a direct reason for the war between England and Holland. However, this is not quite true. According to the report of the English Parliament in 1650, the total amount of trade between the two countries did not exceed 23 – 24 thousand pounds - for the colossal scope of Dutch commercial operations, this was a drop in the ocean. The real reason for the armed conflict was the rapidly accumulating heap of problems, conflicts and clashes between the trade interests of both “corporations” - the British and the Dutch East India Companies. Two dynamically developing and growing predators already had little room for ordinary competition. Their thirst and appetites collided among themselves in Asia, India and Africa.

The conflict was inevitable. In 1652, the situation became explosive. The British handed out letters of marquets to the right and left, the seizures of Dutch merchant ships became frequent. To speed up the situation, the ancient but very audacious edict of King John 1202 of the year was restored, according to which in the English waters all ships lowered their flags in front of the English. In mid-May 1652, the convoy returning to the Netherlands was met by a small English squadron. The requirements of the British for the Dutch to be saluted first were quickly turned into a “horn” discussion using boatswain epithets, where the Dutch word salvo was wider and more active, as the British introduced artillery into the dialogue. After the exchange of cannon "courtesies", as a result of which there were dead on both sides, the Dutch saluted, just in case, but the incident was not exhausted. The vocal cords have not yet recovered from such an intense deck briefing as the new, larger-scale collision occurred.

The Dutch squadron under the command of Martin Tromp cruised off the coast of England in the number of 42 pennants to ensure the safety of returning from the colonies of merchant ships. 29 May 1652 Mr. Tromp approached Dover, explaining his actions by unfavorable weather, and anchored. Further events have several interpretations. According to one, the English governor, frightened by the Dutch, ordered several warning shots from the shore, which they responded with fire from muskets. The other is about the continuation of the dispute, "who is in charge of the seas". The English squadron of Admiral Blake approached the Tromp site, which ultimately demanded a salute from the Dutch, reinforcing its request with warning shots. Tromp responded, and the showdown quickly turned into what went down in history, like the battle of Dover. The battle lasted until darkness, and, although the Dutch were almost twice as good as the English, the islanders managed to beat off two ships from the enemy. Both commanders then exchanged angry letters full of mutual reproaches, which, however, did not prevent further escalation of hostilities.

28 July finally followed the long-awaited declaration of war between the two countries. The first Anglo-Dutch war lasted almost two years. The fighting took place not only in the waters of the North and Mediterranean seas, but also in remote colonial regions. At first, the success came with the Dutch, but in 1653 their fleet suffered two serious defeats. 12 – 13 June Tromp was defeated by the “naval general” George Monk at the Gabbard bank. During the battle, the British, unlike the Dutch, tried to keep a clear wake column, although this did not work out for everyone. Their opponents fought the old fashioned way. The result was the loss of 6 and the seizure of Dutch ships by 11, with very insignificant losses in people from the British. 10 August of the same year was followed by a generally unsuccessful battle at Scheveningen, where Marten Tromp was hit by a bullet from an English ship. Maritime trade suffered huge losses: since the beginning of the war, the Dutch have lost almost 1600 merchant ships, catastrophically reduced the import of fish. The Dutch merchants had already namozolili their fingers on the knuckles of the accounts of computational operations for the study of losses, and they were ready to put up. To hell with it, with this Navigation act and the right of salute, but the business will not collapse. 8 May 1654 between the two countries is signed by the Westminster World, according to which the Netherlands recognized the Navigation Act.

The acquisitions of England in the war, besides moral satisfaction, were insignificant. It is curious that, already in 1657, the possibility of canceling the Navigation Act was seriously discussed in the Parliament, because because of it the prices for colonial goods soared dozens of times. English maritime trade was too weak then and could not compete with the Dutch. Since the first Anglo-Dutch war did not solve a single problem between the two countries, and their mutual competition not only did not subside, but, on the contrary, became aggravated, the start of the second war was only a matter of time.

Restoration in England and the Second Anglo-Dutch War

3 September 1658 died Oliver Cromwell, leaving England ravaged by wars and taxes. Lost in debt the country was on the verge of another civil war. Power was concentrated in the hands of the military, or rather, the most popular of them, George Monk. He acted decisively: 6 February 1660 joined London, February 21 dispersed the already boring parliament to everyone (how often the military coming to power, do not deny themselves the pleasure of carrying out such an exciting procedure!). And then he announced that he was restoring the monarchy in England. 8 May 1660. Charles II, who returned from exile, was proclaimed king in the presence of the “right” parliament. At first, everyone was delighted - even the Dutch, because they recognized for themselves the great merits in restoring the "legitimate monarchical order" in England. Yes, and Charles II did not cause concern. The new monarch began his reign with large-scale reductions and “reforming” the army, resulting in barely more than 80 thousands from 4 in the Kromwellian veterans in the ranks. However, the contradictions in the colonial policy were exacerbated, and the frankly predatory actions of the islanders in Africa became the impetus for a new war with the Dutch.

"Golden Mountain" and the British raid in Africa

In 1660, already under Charles II, the Royal African Company was founded, whose shareholders were large London merchants and members of the royal family. The Duke of York became the head of the corporation, which earned its founders a living by the slave trade and craft, which is called piracy. From a colleague of his father, Rupert of Palatinate (he is the Duke of Cumberland), who wanted to adventure, Karl II learned an entertaining story, according to which somewhere in the Gambia there is a rock consisting of pure gold. Such tales were not uncommon at that time rich in geographic discoveries: what are only the ruinous search for Eldorado, in search of which more than one Spaniard knocked his legs. The British decided to check the information, and in 1661, Rear Admiral Robert Holmes traveled with five ships to Africa, to the shores of the Gambia. The brave admiral did not find a golden mountain or even a golden hill, but he ruined a fort belonging to the Duke of Courland that came along the way and established his own stronghold on the African coast. The Dutch courts met clearly hinted that the English would be the owners of the local waters.

Upon his return, Robert Holmes was rewarded and in 1663 he left for the African Breg as part of the 9 ships. The order issued to Holmes clearly stated: "To kill, capture and destroy someone who dares to interfere with our actions." Of course, the Dutch meant. During 1664, the British carried out blatant attacks on the Dutch colonies in Guinea, the culmination of which was the assault on 1 in May of the Dutch colonial capital of Guinea, Cape Coast, where large prey was taken. All this looked like a full-fledged robbery and military action. In September, the British took control of the Dutch New Amsterdam in America at 1664 in America. In response, in the autumn of 1664, the Dutch squadron of Admiral de Ruyter was sent to Guinean waters to restore the status quo. Having ravaged a number of British settlements in retaliation, at the end of winter 1665, Mr. de Ruyter was ordered to return to England - the situation was rapidly slipping into war.

New war. Battle at Lowestoft

The news of de Ruyter’s actions in Africa provoked a wave of indignation in the British Parliament. The lords thought it was absolutely fair that only they were allowed to attack anyone, whatever they wanted, and as many as they wanted. The Dutch measures to defend their American possessions were deemed criminal and provocative, and on March 4, 1662, Charles II declared war on the Netherlands. When the first anger dissipated, it turned out that the practical Dutch had concluded military alliances with Denmark, Sweden and France. But the British with their allies was tensed. The islanders did not have money for war - fleet equipment required at least 800 thousand pounds. From the bankers of the City of London and the miserly parliament, they managed to shake out no more than 300 thousand. To top it all off, plague hit the capital of England.

In such difficult circumstances, the British decided that the war should feed the war, and were going to improve their financial situation at the expense of the mass seizure of Dutch merchant ships. In early June, a squadron of lieutenant-admiral (commander of the combined fleet) Jacob van Vassenar, baron Obdam, was part of 1665 ships, 107 frigates and 9 ships of other classes. Among this number, 27 ships were armed with 92 guns and more. The number of crews numbered 30 thousand people with 21 guns. This squadron was supposed to meet merchant ships returning from the colonies and prevent the English blockade of the coast. 4800 June 11 The Dutch discovered an English fleet of 1665 ships, 88 frigates and 12 ships of other classes (24 guns, 4500 thou. Thousand crew). The command was carried out by the younger brother of Charles II, the Duke of York. The English fleet was clearly divided into avant-garde, corpsy battalion and rearguard. English ships were better armed and equipped. In the construction of the Dutch fleet, there was complete confusion, as the detachment of each province marched under the command of its admiral. The calm prevented the rapprochement of the fleets, and the opponents soon anchored against each other.

13 June opponents, taking advantage of the wind, began to converge. The Dutch commander took the ships entrusted to him to the west with rather uneven columns, trying to win the wind and put the enemy’s vanguard in two fires. The British turned on the enemy in three columns and dug fire. Shooting at a fairly long distance, both sides passed through the fire and turned around. At this phase of the battle, one ship was lost from the British, which ran aground and was taken aboard by the Dutch. For the second pass, both commanders decided to build their fleets by wake columns, but the English system was more clear and even with more uniform distances between the matelots. The Dutch column was more like an unorganized crowd - part of the ships simply prevented each other from firing. The British smashed his opponent with powerful longitudinal volleys. Under accurate fire, the Dutch system mixed up even more.

Attempt of the flagship of Baron Obdam 76-gun "Eendragta" to board the ship of the Duke of York, 80 gun "Royal Charles", was successfully repulsed, although many of the officers standing on the deck next to the English commander, were killed by the Supporters, abundantly employed by the Dutch. In the midst of the battle, the well-aimed core fell into the Eendragta crew camera (according to another version, the Dutch casually handled powder), and Obdam's flagship flew into the air. This was a turning point in the battle. Centralized command was lost, and now every "provincial" detachment acted on its own. The structure of the Dutch squadron was finally broken, many ships simply began to leave their places and leave the battlefield. By the 7 clock, the Dutch fleet began a retreat, quickly losing organization. In the ensuing pursuit, the British managed to capture or burn 17 ships (9 captured, 1 exploded, 7 captured). The British lost a total of two ships, taken to the boarding. In humans, the losses in the Dutch 4 were thousands of dead and wounded and 2 thousands of prisoners. The British lost 250 dead and 340 injured. The losses of the Dutch would be even greater if it were not for the vice-admiral of the province of Zealand Cornelis Tromp, who managed to organize a cover for the retreat of his squadron.

The second Anglo-Dutch war lasted until 1667, and, like the first, did not solve the problems between the two states. According to the results of the prisoner 21 in July 1667 of the world in Breda, the Dutch received some relief in the Navigation Act: their ships could now transport German goods without hindrance - however, they were deprived of all territories in North America. In return, they received compensation in the South - in the form of a colony of Suriname. And the Dutch city of New Amsterdam has now become English New York. The Anglo-Dutch naval rivalry lasted almost until the end of the 17th century, until it ended with the victory of England.

Information