Anglo-French naval rivalry. The capture of Gibraltar and the battle of Malaga

The war for the Spanish inheritance quickly turned into a pan-European conflict. However, in the eastern part of Europe there was no place for calmness - young Peter I with a bayonet and an ax broke through a high “Swedish fence” on the north-western borders of Russia, in a fierce rush leading Russia into the number of leading states of the world. Ahead were the fields of Poltava, Gangut and Grengam covered with glory and blood. Getman Mazepa also sent loyal assurances to Petersburg, while only secretly thinking about "European integration."

The silver from the New World that arrived on the Spanish galleons played the role of injecting an enriched mixture into the military machine of the Bourbon block. The war absorbed resources in huge quantities and primarily money. Philip of Anjou at the beginning of his reign succeeded in catching nearly fallen financial "pants", gradually asserting power in troubled Spain. Nevertheless, the gentlemen confronting the Bourbons, and not only, matured and formed a logical idea to unleash a war directly on the Iberian Peninsula, actually in the rear of Louis XIV. An unsuccessful landing attempt at Cadiz in 1702 year spoke of the need for more thorough preparation and a “creative” approach. Mindful of the very recent attempts by Jacob II to establish themselves in Ireland, it was decided to try to do the same in this situation. Only instead of a runaway king, expelled from his own country with little effort, it was decided to export none other than a candidate from the anti-French coalition of the Austrian Archduke Charles, for the convenience of naming the advance made in Charles III, the king of Spain. With the help of this figure, Louis’s opponents planned to start, without any doubt, the popular and, of course, the liberation struggle against the “usurper”, the “illegal heir” Philip of Anjou.

It was decided to start the enterprise not from the Spanish territory, but from a preliminary disembarkation in Portugal. On the one hand, there was a good excuse along the way to the Spanish throne to screw Lisbon to the anti-French coalition, on the other hand, the ports of this state would be convenient supply points for the upcoming operation.

New "partners" of Portugal

Portugal, which only relatively recently became an independent state (for some time it was part of neighboring Spain), was a profitable ally because of its geographical location. Initially, this small state was in the sphere of influence of France, but those who already knew a lot about diplomatic combinations “enlightened sailors” decided to rectify this situation. In May, 1703 was signed by the English envoy of Lord Methuen and the first minister of Portugal, Marquis Alegrete, to the Lisbon Treaty (the essence and results of which painfully resemble the “association” signed a little more than 300 years later with another amazing country Pedro). The British, very skillfully playing on the aspiration of King Pedro II to strengthen their independence from Spain, did not skimp on the promise of help with troops and other resources (hard currency, of course), all kinds of patronage, well, and a little more Spanish land after victory. For Pedro II, who, in principle, had one Spanish king too much, it was, as he thought, a chance to sit out far from a serious fight. But the British were already great sharks then: for the so-called "help" the Portuguese allowed the English commercial capital into their economies and colonies and lost disproportionately more. In fact, the country became a vassal of Great Britain. Nevertheless, the agreement was signed willingly - island benefactors seemed so kind and generous. The charm of the situation and the argumentation “for” was added by the British squadron, who accidentally entered Lisbon.

Thus, with very modest costs and vague guarantees, the British got themselves a new ally. Now, on the European chessboard, the move was granted to the candidate of the most, without any doubt, progressive forces - the Archduke Charles.

In the autumn of 1703, an English squadron left the Netherlands, in which another king of Spain was located. The first part of the plan was successfully implemented - Portugal from a relatively independent state became an “ally and partner”. Of course, the younger. Diplomacy stepped aside, giving way to less graceful, but much more effective arguments in the conduct of business. February 12 squadron of 35 battleships under the command of George W. Hand, already filled his hand in successful and not very campaigns to the Iberian Peninsula, arrived in Lisbon. King Pedro and his entourage arranged for their valiant ally and partner a magnificent meeting. The impetus for proper pomp was that Admiral Shovel joined the Hand with 23 battleships, 68 transports and 9 by thousands of soldiers of the expeditionary force. Although Pedro showed his most sincere allied intentions very carefully and assertively, the British believed that it was now possible to transfer the war to the territory of Spain itself in order to seize the ports and harbors that would be controlled only by them, in order to reduce dependence on the Portuguese.

It cannot be said that the French looked thoughtfully and sleepily on these movements and voyages of all kinds of "candidates". Upon learning of Ruka’s exit, the Brest squadron attempted to intercept it, but unfortunately, when leaving the harbor, one of the 25 battleships swooped down on the underwater cliff and blocked the fairway. There was a chance to use the Toulon squadron for hunting the archduke, but the young maritime minister Jerome Pontchartrin simply ... withdrew money from the treasury intended for equipping the 27 battleship. What to do if the minister urgently needed funds to resolve his personal issues? One way or another, the opportunity to intercept the British was lost.

While Minister Ponchartren drove income and expenses to acceptable levels, the commander fleet The Levant (that is, the Mediterranean) Count of Toulouse bowed him in every way, using the boatswain vocabulary, "enlightened sailors" mastered in the Pyrenees. When the initial enthusiasm caused by Carl’s visit subsided, the active Hand decided to sabotage Barcelona. He left Lisbon with a part of his forces and a landing force of 1800 people. However, Barcelona was ready for defense, and the British landing failed. Rook soon received instructions from London, in which, among the priority goals, he was given Cadiz, which he never took two years ago. I frankly did not want to climb into this well-fortified port, but the order is the order. In July 1704, an Anglo-Dutch squadron approached Cadiz, and, still not wanting to put his hand in a voluminous and strong hornet’s nest, Rook convenes a military council aboard his flagship Royal Katherine with a characteristic statement of the question: “What to do?”

The fact is that the admiral, like the commander of the landing squad of soldiers and marines at 2000, Prince of Hesse-Darmstadt, rightly believed that such modest forces were not enough to storm a well-fortified city with a strong garrison. But at the same time there was an order on the hands to land and attack. The foreseen way to carry out orders would be littered with bodies in red uniforms, smoking ships, a subsequent trial, and something worse. The easier way is quite shortened the distance to the court and practically guaranteed something worse. Passions in the Royal Katerina mess were raging on the Atlantic storm, until someone (namely Vice-Admiral John Leek, junior flagship) uttered, but practically abandoned, like a life preserver, the word "Gibraltar." Venerable gentlemen came to life. It was known that the enemy forces in this fortress are small, and the actual number of soldiers is more than enough to capture it. Of course, there was a clear failure to comply with the order of command. But, on the other hand, the admirals hoped that Gibraltar was in principle “almost Cadiz,” that is, they would land and capture. As the wise uncle Fedor used to say, “it’s a hunt and you don’t need to kill animals”. And the fact that the wrong harbor was chosen, so the winners are not judged.

Rock

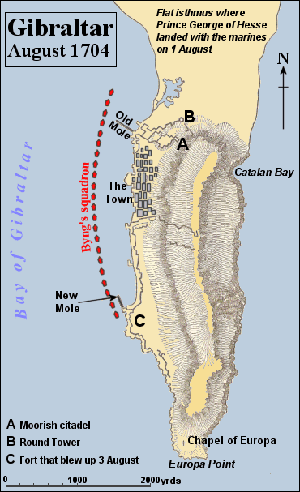

Gibraltar is a rocky narrow cape in the very south of the Iberian Peninsula. Its extremely favorable geographical position was assessed long before the events described. The first to equip here for their ships were the magnificent navigators of antiquity, the Phoenicians in 950 BC. er They were replaced by the Carthaginians, and then the Romans. But the Arabs really appreciated this place. 30 April 711 was the year that Tariq ibn Seid’s troops, who had begun the conquest of Spain, landed in this area. The city of Gabal-al-Tariq was founded on an important place. In 1160, a citadel was immediately built, and by 1333, the Moors had built an even more powerful fortress. 20 August 1462, in the last decades of the Reconquista, the troops of Castile under the command of Alonso di Argos took the Moorish fortress by storm. The Spanish monarchs attached great importance to Gibraltar. Isabella of Castile (favoring Columbus) instructed to hold this stronghold, covering Spain from the African coast, at any cost. In the following centuries, its fortifications were strengthened.

By the events described, Gibraltar experienced not the best of times, however, like all of Spain. Economic and military decline has turned a strong fortress into a provincial backwater. The main fortifications were an irregular quadrilateral, the eastern and southern walls rested directly on the rock, the western - into the bay, and the north on the isthmus was covered with the bastion of del Castillo, on which guns were not installed. However, not on it alone - the forts and the citadel were equipped with platforms for the installation of more 150 guns. Heightened curiosity of the English to Cadiz made the Spaniards strongly strengthen it, disarming for this other fortresses. Such disastrous realities of the garrison of this strategic object evoke an association with the Pushkin Belogorsk fortress. Under the command of the governor of Gibraltar, Don Diego de Salines, there were only 147 soldiers and 250 militia armed with what God sent. Most of the guns, which numbered about a hundred, were aimed towards the sea. Thus, from land, the fortress was virtually defenseless - the main obstacle for storming here were the rocks. The garrison was in great need of food, and especially drinking water.

1 August 1704, the allied fleet consisting of 45 English and 10 Dutch battleships appeared in view of the fortress. The English parliamentarians handed two letters to Don Salines: the first from King Pedro II, who recognized the Archduke Charles as king of Spain, and the second from the Prince of Hesse-Darmstadt, who assured in the most courteous terms that the Allies would not do anything bad and go away as soon as the fortress swears loyalty to Charles II. The governor, in general, did not care that one alien king recognized another self-appointed king. With the same success, he could be informed of the recognition of Charles by some Senegalese tribal leader. Don Salines did not at all believe the British with their “good” wolf intentions. He ordered to prepare Gibraltar for defense. While the English troops, waiting for a response from the opposing party and guided solely by "peaceful" intentions, landed on the shore, the Spaniards dragged six guns into the bastion of del Castillo - positions were occupied by 70 soldiers there. The rest of their very modest forces Salines distributed in threatening areas: on the isthmus behind the bastion at the northern and southern moles. The Spaniards had only a scanty amount of weapons for the guns, otherwise it would have been possible to inflict very significant damage to the enemy ships that were located near the coast. For antisurge fire, there would be enough grape-shots and other scrap metal charged into guns.

2 August was blowing strong wind, the squadron Ruka could not approach the shore, but for the pro forma it made several cannon shots, showing that the British are waiting for the Spaniards to have a “constructive dialogue”. In the evening, the wind changed, and the shock group consisting of 22 battleships and 3 bombarding ships under the command of Vice Admiral Bing approached the distance of effective fire. Having decided that the enemy simply pulls time, the British fired several artillery volleys. The fortress immediately responded. No contracts and compromises - now spoke guns.

On the morning of August 3, Bing began the bombardment of Gibraltar, which lasted approximately 6 hours. On the fortress was released about 1400 cores. Actually the fortifications themselves suffered little - the destruction was among civilian buildings. Approximately 50 militiamen and a half hundred civilians were killed and wounded. From the city began the exodus of the civilian population, many took refuge in nearby monasteries - Nuestra Signora de Europa, San Juan and others. Under the cover of ship guns and seeing that Spanish fire is rare and inefficient (a small number of cores), a large squad of royal marines commanded by Captain Whitaker is landed on the northern mole. The nearby fortifications of Muela Nuevo defended all 50 militias. The Spaniards decided to retreat, but the Englishmen had previously made an unpleasant surprise by blowing up a mine. 42 Englishman were killed, 60 - injured. Nevertheless, Whitaker took the fortification itself, and the nearby monastery Nuestra Signora de Europa, which hid many women and children. The position of Gibraltar was not critical - Hesse-Darmstadt was still trampling on the isthmus, not daring to storm the bastion of del Castillo. The loss of Muelle Nuevo also did not make a fatal flaw in the defense.

However, the inventive "enlightened navigators" approached the matter creatively. They had more substantial arguments left over. At noon, Don Salines received a new message that looked more like an ultimatum. Without special sentiments, the Spaniards were asked to surrender to the fortress. Otherwise, the Allies threatened to assassinate the entire civilian population during the assault. And they planned to start his extermination with the refugees in the captured monastery. There was a rough blackmail. The garrison soldiers, whose wives and children had actually become hostages of the British, began demanding from Salines to accept the conditions of the enemy, although the fortress had far from exhausted the ability to resist. After a brief meeting with his officers, the governor signed an honorable surrender. Under the drumbeat and with the banners unfolded, the garrison cleared the fortress. Women and children from the monastery were also released and left with the troops. The capture of Gibraltar, this key point, the gateway to the Mediterranean, cost the Allies about 60 dead and 200 injured. The adventure, dangerously balancing on the verge of failure, turned into a military success. Who knows what the siege would have ended if the Spaniards had more cannons, nuclei for them and a numerous garrison. Nevertheless, the fact remains: Gibraltar was captured.

Most of the civilian population left the city because of looting and violence by the British and the Dutch, who ruined Catholic monasteries with particular pleasure. The hands left in the fortress a strong garrison of almost 2 thousands of people, supplying them in abundance with gunpowder, kernels and provisions. The possession of Gibraltar promised the royal fleet numerous benefits. First of all, it was valuable as a place for parking ships. The fortress allowed to influence the whole trade of the enemy, hindering the unimpeded transfer of the French fleet from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. It was not a splinter - it was a deep-sitting, painful thorn in the south of the Iberian Peninsula for the Spaniards and their allies, the French. Upon learning of the loss of Gibraltar, Philip of Anjou ordered to take emergency measures to repulse him.

Fight with Malaga, or Why Mentors Are Needed

No sooner had the new owners of Gibraltar unpacked their suitcases and settled on the ground, as a squad of Spaniards of about 8 thousand people was sent to the walls of the fortress. Soon no less than 3 of thousands of French were to join them. Of course, these forces were not enough to storm the rapidly reinforced and tidied Gibraltar. The detachment was to perform blocking functions until reinforcements with siege artillery were suitable. They decided to approach the pulling out of the English thorn in a complex manner - a fleet was sent to the coast of Spain. The treasury was shaken up properly (in such cases it was no longer a matter of economy), and practically the entire fleet of the Levant came out of Toulon under the command of Vice-Admiral Victor Marie d'Estre as part of the 50 battleships and 10 galleys. In the area of Barcelona, 11 large galleys, under the command of the Count of Toulouse with 2 thousands of infantrymen on board, joined this grouping.

On August 22, the English frigate Centurion, which had performed the functions of the long-range patrol, noticed the French fleet moving in the direction of Gibraltar. Having received information about the enemy, still remaining in the Gibraltar region, Rook decided to attack the French, wanting to add success to the land to the victory of the land. The British admiral was confident that the French would shy away from the battle and simply return Toulon. Rook moved towards the intended course of the enemy fleet. He had 45 English and 10 Dutch battleships and some smaller ships. 24 August morning, the two opposing fleets saw each other, or rather, the enemy of the enemy south of the Spanish Malaga.

The squadron Ruka moved in the standard order for that time. Avant-garde included 15 battleships, 3 frigates and 2 firefighters under the command of Claudis Shovel. The center, consisting of 26 battleships, 4 frigates, 4 firefighters, 2 bombarding ships, was led by George Rook himself. The rearguard, in which the 12 of the Dutch battleships, the 2 of the bombing ships and the 1 frigate, were flying, was under the flag of Lieutenant-Admiral Kallenburg. Despite the fact that there was weighty hope for the retreat of the French, Rook grabbed all that was possible from under Gibraltar, including bombing ships. Subsequently, they rescued the British well.

The French were determined to fight. The avant-garde of the Levant fleet consisted of 17 battleships, outside the line were the 8 Spanish galleys, the 2 frigate and the 3 firefighter. Commanded all this Lieutenant-General Willett. Cordebatalism included the 17 of the battleships and off-line 1 haliots, the 6 French galleys, the 2 frigate and the 5 branders under the flag of d'Estras and the Duke of Toulouse. The rearguard line was closed by lieutenant-general Langeron from 17 battleships, 3 frigates, 2 firefighters and 8 galleys.

Due to the specifics of the situation, both units (some had already stormed the fortress, others were just preparing for this) had a large number of ships outside the battle line that served as support. Contrary to expectations The hand of the French did not flinch, but began to prepare for battle. The British were in the wind and planned to rapidly move closer to the enemy, to break through the system and force them to withdraw. The French sought to cover the enemy column and put the Anglo-Dutch fleet in two flames. Both fleets approached, and soon the battle began between the vanguards - gradually both lines were drawn into battle.

Interestingly, the English bombardier ships also took an active part in the battle. Tears of heavy mortar bombs, if, of course, it was possible to hit, caused serious damage to the enemy. For example, one of the French battleships from the avant-garde "San Phillip" was hit by such a projectile in the feed superstructure - there were stored some amount of gunpowder and nuclei for the upcoming battle. The explosion caused severe destruction, killing and injuring more than 90 team man.

In general, the battle near Malaga resulted in following in the wake columns in parallel to each other and maintaining hurricane fire at dagger distance. For a long time, the outcome of the battle was unclear - both sides fought with great tenacity and bitterness, and the density of artillery fire impressed even veterans. Subsequently, Rook, who had been in many large and small battles, argued that he had not previously seen such an artillery battle. Damaged French ships were put out of action by galleys to clean up, after which they returned. But the fire of the Golden Lilies fleet was still a bit more efficient - by the second half of the day the English battleships 11 came out of battle as a result of severe damage, on many ships the gunpowder that had been so generously released to Gibraltar from the ship stocks came to an end. The French line was also upset - rare, but very tangible hitting bombs made terrible damage. So, 60-gun "Serje" lost rigging, a fire broke out on it, the ship lost control. However, the approached galley, “tow truck,” towed the damaged battleship behind the battle line, where he was able to repair the damage. If the fire from the bombard ships would be more accurate, the French would not have been more healthy.

The intense cannonade, without any sophisticated tactical maneuvers, lasted for several days with small interruptions and only subsided by the 21 hour, when the rearguards of the opposing sides finally dispersed. Both fleets were exhausted by the battle, both had a lot of damaged ships. After the battle, the Dutch lieutenant-admiral Callenburg transferred his flag from the Count Van Albermarl flagship to Katviyk. It was decided to distribute the remaining powder between the other Dutch ships, however, an explosion occurred during the overload, and the “Graf van Albermarle” took off into the air - almost 400 crewmen died. It was the largest loss of the Anglo-Dutch forces. Their total losses per day were 2700 people, the decline of the French was almost 1700 personnel. The position of Ruka was serious: the powder was running out, and many ships were unable to give a new battle. However, the next day, 25 August, the enemy did not attack. Opponents dispersed, although it seemed that a new battle was imminent.

26 August on the French flagship, 102-gun "Soleil Royal", named in honor of the famous ship Turville, held a military council. The main topic for discussion was the same main question: “What to do?” Most of the flagships and divisional commanders were against the battle. Lieutenant General Willett expressed the general opinion that the honor of the fleet and the king had been saved, and it was dangerous to risk a league from Toulon on 300. This view was somewhat strange, since the Hand was even at a greater distance from Gibraltar. You can, of course, understand another famous Frenchman who almost a century later in the final of a large-scale battle in a harsh and very unfriendly country declared his marshals: "In several thousand leagues from Paris I cannot sacrifice my last reserve." But the Mediterranean Sea at that time was almost completely controlled by the Levant fleet. Admiral d'Estre was in favor of a new battle, because he understood that a weakened enemy could and should be finished. A similar disorder in command was caused by a two-starter in the Toulon squadron: actual leadership was carried out by d'Estré, but formally the young graph was headed by a young Count of Toulouse. The young man bravely showed himself in battle, was wounded in the arm, head and side, and yet spoke out for the fight.

But then the moment came when the levers stories It turns out people are random, unnecessary and insignificant. The problem was that the count fought under the supervision of a mentor in the naval cause, Mr. d'O, the main advantage of which was exorbitant arrogance and arrogance. Having never been at sea and commanding anything larger than a personal bath, this expert assigned to such an important post considered himself entitled to intervene in the command of the fleet, without having any rights to it. The land giant of sea thoughts provoked a sharp hostility among the admirals, so if one chose between awarding the Order of St. Louis and the possibility of dragging Mr. D'O with impunity, it would be very difficult to make a decision. Anyway, the master, who is present at the council, referring to instructions from the king himself, called for organizing a vote (!) - whether to give battle or not. Much to the chagrin of d'Estre, the majority spoke out against the battle. A brilliant case to finish off the Anglo-Dutch fleet, tightly blocking Gibraltar from the sea, depriving it of supply and thus forcing to inevitable surrender, was missed. More such an opportunity to the French did not appear. The fleet returned to Toulon.

Both sides attributed the victory of Malaga to themselves, however, from a strategic point of view on the situation, success undoubtedly belonged to the Hand, despite the less successful (in terms of losses) end of the battle. The Allied fleet regained its combat capability; it could supply the garrison of Gibraltar with everything necessary in the future. The siege of the fortress without sea blocking was more than problematic. The war for the Spanish inheritance continued, the swords were still sharp, the cores were red-hot, and the sleeves of expensive camisoles were still soaked in blood.

The struggle for the Rock will be long and hard throughout the 18th century, but the British Union Jack is still arrogantly flying over it.

Information