Wake-up in Dardanelles, or Fight at Imbros Island

By the end of 1917, the position of the Central Powers was more than serious. Despite some successes in the Eastern direction - the conclusion of an armistice with Russia - Germany and its allies were burdened with several fronts at once. The resources, both material and human, were coming to an end, the possibility of their replenishment was more than doubtful: the very limited reserves that the Germans had had to literally juggle, constantly transferring them between theaters of military operations. The Ottoman Empire, a large but in many respects archaic state, received blow after blow from the Entente in various parts of its still extensive possessions. The senior partners in the bloc, Germany and Austria-Hungary, could not single out a single extra division to help their weary ally.

10 December 1917, the British troops entered Jerusalem. This event had a very depressing impression on both the Turkish public and the morale of the army. The situation on the Palestinian front was difficult, so the news of the transfer of the two Allied infantry divisions from the Balkans through Salonika to Palestine was perceived by the Turkish command very painfully. It called on the commander of the German-Turkish naval forces, Vice-Admiral von Rebeir-Paszwitz, to take measures to disrupt or postpone the transfer of Allied troops to the Middle East.

The end of 1917 was marked by the expected end of the dense blockade of the Bosphorus from the Black Sea by Russian forces fleet. After the October Revolution, an already precarious disciplinary balance was upset: the ships and bases of the Black Sea Fleet were swept by a wave of socio-political changes and transformations. And, of course, not for the better. It should be noted that the Russian blockade was a very effective and efficient way of influencing primarily the Turkish capital Istanbul and the German-Turkish naval forces based here. Due to transport paralysis, the bread ration was reduced to 180 grams per day, the ships stood with a scanty amount of coal, not having the opportunity to go to sea. Only destroyers, due to their speed, periodically went to Zonguldak, where they bunkered with coal. On the night of December 15-16, a truce was concluded with Russia. The vise of the coal and food blockade, which has been weakening in recent weeks, has now completely cleared.

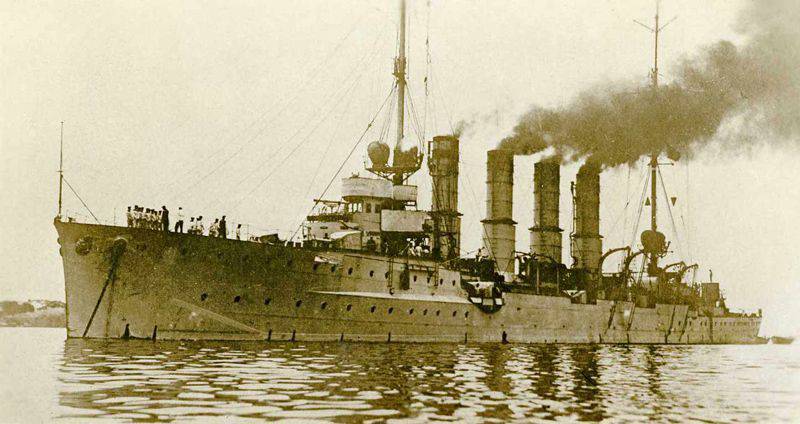

In the changed situation, the request of the Turks about the raid on Thessaloniki reached the German naval headquarters in Berlin, where, having estimated the pros and cons, they gave the go-ahead to the operation. The actual commander-in-chief of the Turkish army, Enver-Pasha, recommended not to risk without need and not to engage in battle with the superior forces of the enemy. The fact is that the battlecruiser “Goeben” and the lightweight “Breslau”, which planned to make some noise at the Greek coast, were to be finally transferred to Turkey’s possession, by prior arrangement, after the war ended. Enver Pasha, in his wishes, von Rebeir-Pasvitsu stressed that these two ships are for Turkey as the Grand Fleet for Great Britain. In general, the Turks were not against sabotage, but against risk.

Planning and preparation of the operation

After the exchange of telegrams with Berlin, preparations began for the raid operation. First of all, it was necessary to solve the problem with coal. On 21 December 1917, the battle-cruiser “Goeben” had in its coal holes no more than 1385 tons of coal with a full supply of 3000 tons. Breslau, on the other hand, was sitting on a starvation ration - he had only 127 in tons instead of the laid 1200. All this was a consequence of the Russian blockade and the coal crisis caused by it. With such a quantity of available fuel, it was impossible to think about immediate release to the sea. In the second half of December, the most combat-ready Turkish destroyers made the transition to Zonguldak, where they received coal. On December 21 it was Breslau's turn, for which it was not a problem to take fuel from the mole. With “Goeben” was more difficult. Due to heavy rainfall he could not come to the shore. On January 15, the battle cruiser arrived in Zonguldak, embarked on the outer roadstead and filled his vast bunkers with fuel from barges for three days. January 18 "Goeben" was fully supplied with coal.

Having resolved the fuel issue, the naval command proceeded to operational support. Channels in the minefields of the Dardanelles fortress were expanded from 75 to 200 meters for normal passage of ships. Simultaneously, work was carried out on the reconnaissance and trawling of enemy minefields. In order not to provoke the enemy ahead of time, this set of activities was carried out mainly at night and at the last moment. Great attention was also paid to high secrecy: a very narrow circle of officers was devoted to the plan of the raid operation, even the command of the 5 Turkish army in Gallipoli was not informed about the upcoming action.

During the planning process, the tasks of the raid group were formulated more clearly and more moderately in contrast to the original idea. Almost immediately, ideas of a breakthrough to Thessaloniki were followed, followed by a shelling of the port. The task of the detachment, above all, was to strike at the forces of the enemy, directly guarding the exits from the straits. The German-Turkish command was preoccupied with conducting air reconnaissance of the British forward bases on the islands of Lemnos and Imbros — fighter aircraft were requested for this. Since part of the British auxiliary ships were located at anchorage, special prize parties were introduced into the crews of “Geben” and “Breslau” - the Germans seriously expected to take trophies. With luck, it was planned to bombard the British seaplane base on Imbros Island and the Bay of Mudros on Lemnos Island, where the English light forces stationed. The only combat-ready submarine UC-23 was involved in the operation, it was supposed to be called on the radio from the position it occupied. In addition to both German cruisers, the most combat-ready Turkish destroyers, the Muawenet, Basra, Numune and Samsun, were deployed. All ships were provided with fuel, preliminary work on clearing the fairways was completed, and it was no longer possible to postpone the operation - the British intelligence could record activity in the straits and take appropriate measures. By the evening of January 18 and 1918, all the coastal batteries of the Dardanelles Fortress were on full alert.

Watch at the Straits

By the end of 1917, the British ship group, which had taken positions with the Dardanelles, began to resemble a squadron guarding a cave with a dragon. Everyone waited and waited for the dragon, but he did not go out. And, finally, so accustomed to this state of affairs, that the appearance of a dragon from the cave seemed no more real than the dragon itself. It became customary for the British that all the troubles associated with hunting for “Goeben” and “Breslau”, for many years of the war bore the Russian Black Sea fleet, which was, from their point of view, the normal order of things. The panic hypotheses that the “Goben” would suddenly burst into the expanses of the Mediterranean Sea, causing death and destruction, were ridiculed not without reason, and the passions subsided.

By the time of the Rebeir-Pashwitz operation, the British naval forces in the Aegean Sea had been reduced to two battleships of the predetermined type “Lord Nelson” and “Agamemnon”, eight middle-aged light cruisers, a flotilla of old destroyers and several monitors. Armadillos could give a maximum of 18 nodes. “Goeben”, although it was no longer a good walker - the bottom overgrown during the war made itself felt, could develop the speed of the 22 node. Under very favorable circumstances, the British could count on something like a battle at Cape Sarych - 2. Fortunately for the Germans, shortly before the events described, the command of the Aegean squadron was taken over by Rear Admiral Arthur Heyes-Sadler, who was the commander of the Oceanic dreadnought on the day of his death in March 1915. The rear admiral tried to reduce the number of the very "favorable circumstances" of capturing Istanbul sidelts to a minimum. So, for his official visit on official business to Thessaloniki, Sir Hayes-Sadler chose not some Triad headquarters yacht, specially located for such cases on Mudros, or a destroyer, but an entire battleship Lord Nelson. The rear admiral divided his already not enormous forces into as many as six detachments scattered throughout the sea. For some reason, the British command was firmly convinced that any exit of the German ships from the straits would be preceded by a long and thorough trawling of the fairways. It was wrong. The Germans managed to catch the enemy by surprise.

Dardanelles wake

In 16 hours 19 January 1918, the squad went to sea. January 20 3 30 minutes "Goeben" and "Breslau" were at the exit of the Dardanelles - when their own minefields were behind, the pilot was released, and the destroyers were ordered to turn back. Initially, two of them were to be accompanied by German cruisers, but they refused this undertaking - the Turkish destroyers, according to the German command, were not fast enough and had weak weapons. The chosen route was influenced by one important circumstance. December 20 On the island of Enos in the Saros Gulf, 1917 sat on the stones and captured an English steamer. It found a map of the waters adjacent to the Dardanelles, with various marks. The commander of the 5 Army, General Liman von Sanders, handed this document to the naval command, believing that it would benefit from it. Signs and other symbols were interpreted at the headquarters of the operation as a scheme of English minefields with safe passage through them. The data obtained caused skepticism and distrust in some officers. The places on the map already thoroughly polished by the Germans were marked and interpreted as mined. But the areas without any marks and badges by German intelligence were rated as potentially dangerous. Intelligence did not coincide with incomprehensible marks. Nevertheless, great importance was attached to the planning of the upcoming operation of a captured English map with questionable content. On the basis of the data obtained from it, the intended course of following Geben and Breslau was laid.

In 5 hours 41 minute German ships left the strait. The observation post, located on the island of Mavro, because of poor visibility and fog out of the enemy did not notice. In 6 hours 10 minutes, being according to the English map in a safe place, "Goeben" left side touched a mine. There was an explosion that did not, however, cause much harm - the battle cruiser retained its combat capability. After a preliminary inspection, a buoy signaling danger was dropped into the water, and the ships headed for Imbros Island. Breslau received an order to move forward to detect enemy ships. The Goben itself in 7 hours 41 minute opened fire with an auxiliary caliber on a signal radio station on the Kefalo spit - after four volleys it was destroyed. The battlecruiser transferred the fire to two small vessels stationed at the shore, and soon sank them. The first German ships were discovered and identified by the British destroyer Lizard on patrol off the northeast coast of Imbros Island. German radio stations jammed the broadcast, and the British were not immediately able to notify their colleagues about the sudden danger. According to the memoirs of the Lizard commander, Lieutenant Olenshlager, at the time of the detection of the enemy he was in the navigational cabin. When his watch officer reported that he was observing a ship similar to a cruiser coming from the Dardanelles, and believed that it was to Breslau, Olenshlager sternly scolded him, being deeply convinced that this was some kind of annoying absurdity and inattention of the young subordinate. The British believed in the Germans ’raid no more than the output of the entire High Sea Fleet. Nevertheless, the commander of the Lizard very soon became convinced of his mistake. The British were still hastily setting up their binoculars when lights flashed along the dark, impetuous silhouette of a four-pipe ship, and in the next moments around the English destroyer the pillars of ruptures rose. The air cracked due to interference, and therefore Olenshlager attempted to visually transmit a signal of danger to two British monitors, Raglan and M-28, located in Kusu Bay of Imbros Island.

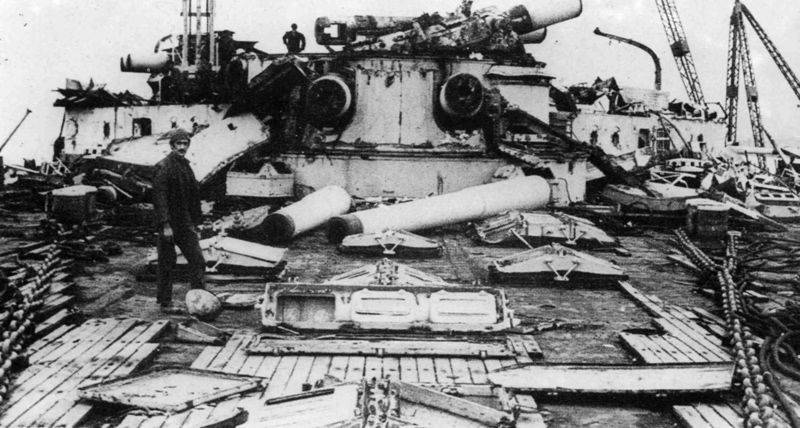

About them it is worth saying a few words. During the outbreak of war, the Englishmen, who were conducting military operations in various maritime theaters, were in dire need of small-board ships armed with heavy-caliber artillery. And then they remembered the already half-forgotten class of monitors. The Abercrombie series of marine monitors, to which the Raglan belonged, was ordered in the fall of 1914. Armed with these ships were 356-mm tools purchased from the United States for the Salamias dreadnought, which was being built in Germany by order of Greece. The Raglan had two such weapons located in a massive turret. The second monitor that makes up Raglan, the M-28, was a type of small monitor, which, however, had a serious 234-mm gun and an 76-mm anti-aircraft gun for the enemy.

The crews of both ships were engaged in Sunday routine activities when the urgent semaphore from the Lizard was received with the GOBLO code signal - the German cruisers left Dardanelles. The dragon that had emerged from its lair destroyed the settled peace of its guards. Standing on anchors "Raglan" and M-28 urgently played the alarm. Raglan, which has a powerful radio station, was able to transmit news of the German withdrawal of the Agamemnon standing in the Bay of Mudros, who rehearsed it directly to Heyes-Sadler in Thessaloniki. But the Germans did not allow the British to come to their senses - monitors caught off guard were too tempting prey, which had to be prepared, and urgently. In 7 h. 44 min., Having driven off the British “Lizard” and the “Taigriss” that joined it, “Breslau” opened fire on fixed monitors standing at the coast. He was soon joined by the “Goeben”, which launched its main caliber. At first, the British did not open fire, believing that the enemy would not notice the monitors painted in camouflage, but this was completely in vain. Already the fourth salvo "Breslau" turned out to be effective - on the Raglan the fore-mars was destroyed, the senior artilleryman was killed and the captain of the ship, Capt. 2 of the rank of Viscount Broome, was wounded. The British managed to make only seven ineffectual shots from the auxiliary 152-mm guns, when the Germans were shooting at them and started projectile-by-projectile. The monitor tower was ready to open fire, but the 280-mm projectile from the Gebena broke through the barbet and ignited the charges at the elevator. The fire in the tower compartment was avoided, with some of the servants killed. Seeing that the monitor, deprived of its main artillery, was in a hopeless situation, Broome ordered the crew to leave the ship.

The Germans moved the fire on the M-28. Already the second volley caused on him a strong fire. The Lizard, who tried to help his dying comrades and put up a smoke screen, was driven away by artillery fire. Both German cruisers came up to a distance of no more than 20 cable and quietly shot the monitors as targets on the exercises. Soon, the heavily damaged Raglan, on which the cellar of 76-mm guns exploded, sank at a depth of about 10 meters. M-28, who managed to give two shots from his main caliber, was all enveloped in flames. A little later he exploded and also sank. Of both the crews survived and were picked up from the water 132 man. They spent very little time on the reprisal of the two monitors “Goben” and “Breslau” - not seeing worthy targets before them, they continued to move south to then move towards the Bay of Mudros.

"Goeben" experienced some difficulties with determining its exact course, because due to the detonation of a mine, all gyrocompasses failed. At the beginning of the ninth from the wake in the wake of the battle cruiser Breslau, they signaled that they had discovered an enemy submarine. This was an obvious mistake, since there were no Entente submarines at the moment. The British destroyers "Lizard" and "Taygriss" held on to the stern of the German detachment, not losing sight of them. Two enemy aircraft appeared in 8.26, and from the Geben they ordered the light cruiser to come forward - the flagship wanted to use its anti-aircraft guns without threatening the Breslau. Soon the first bomb fell into the water.

While Rebeir-Paschwitz fought back from the planes and destroyers that were annoying him, an already stagnant military countermeasure was put into effect in the camp of the opposite side. Having received a radiogram from Lizard, Heyes-Sadler hastily left Thessaloniki, holding his flag on Lord Nelson. He ordered on the radio "Agamemnon", whose fireboxes already in full swing fired firemen, go out to meet the flagship and, having joined, try to intercept the "Geben". Throwing into the battle of one "Agamemnon" English admiral considered it too risky. The old scout cruiser Forsyth, which is preparing to leave with it, was frankly weak even for the Breslau.

While awakened the British raised a fist to counter the threat, the Germans themselves faced very serious problems. In 8 hour. 31 min., Performing a maneuver, "Breslau" stern of the starboard hit a mine. The steam and manual steering gears, as well as the right-hand low-pressure turbine, failed.

On a minefield

The cruiser remained afloat, but lost control. The commander of "Goeben" captain 1 rank Stenzel ordered to turn around to go to the "Breslau" and take it in tow. Meanwhile, light cruiser observers noticed anchor mines in several places - the visibility was excellent and the water had a high degree of transparency. On the "Goeben" they transmitted a warning about the danger by a semaphore - he slowed down and approached his friend with caution. However, it did not help. In 8 hours 55 minutes a large pillar of water suddenly rose from the starboard side of the Geben, flying up above its masts, - the water carried the form-bram to its stump, fortunately, without damaging the radio antenna. The information from the trophy card was interpreted completely incorrectly. Some personal, one known to him, marks of the English captain, adopted by German analysts for the location of minefields, became a trap into which the von Rebeir-Pashwitz squad landed. Cruisers found themselves actually in the middle of the enemy’s minefield. Seeing the mine explosions, the British destroyers were somewhat bolder and shortened the distance. However, the wounded enemy remained dangerous. The Breslau stern guns opened frequent fire and again forced the Lizard and Taigriss to move a respectful distance. On the light cruiser, the struggle for survival continued. The emergency parties managed to localize the flow of water, on the deck they were preparing to receive tugboats from the Geben. The captain of the 1 rank Hippel, the commander of the Breslau, gave the order to back up in order to get out of the ring of mines discovered.

But the cruiser troubles have just begun. At about 9 hours, two explosions immediately struck - they fell on the left-hand boiler department. Breslau now lost not only control, but also progress, and began to drift with a list to the left side and aft on the stern. Approximately in 10 minutes two more explosions occurred. Hippel ordered the crew to leave the cruiser immediately. The agonizing ship began to sink astern and soon sank. The British destroyers "Lizard" and "Taygriss", passing by the place of death of "Breslau" in an hour and a half, lifted a man from the water 162. "Goeben" could not afford to conduct rescue and began to get out of the minefield. After contacting the base, he requested the immediate arrival of the destroyers so that they could save at least part of the crew of the light cruiser. Four Turkish destroyers, standing in full readiness at the exit from the Dardanelles, immediately set sail. Already there could be no question of the shelling of Mudros harbor, or of other sabotage - the main task at this point was to ensure the return of "Geben." Not reaching about 5 km to the place of Breslau’s death, the Turkish destroyers engaged in battle with the same Lizard and Taigriss. And this time, the British shot accurately: “Basra” received two painful hits with 102-mm shells, one of its compartments was flooded. The Turks decided not to tempt fate and turned back. The British destroyers drove them until they came under fire from the coastal batteries of Fort Sed el-Bar.

The command considered the command unacceptable to use the precious battle cruiser to cover their own destroyers even to save the remnants of the Breslau crew, and the Goeben received an order to return immediately. The Germans could not find the buoy they exhibited early in the morning — this annoying mistake had cost them dearly. In the 9 hours of the 48 minutes the battleship once again hit a mine near the place that it was the first time. The damage was again not critical, and the ship continued on to the Dardanelles. Rear Admiral Hayes-Sadler, who was rushing from Thessaloniki with the entire 18-node speed of a middle-aged ship, was aware of the events taking place thanks to regular radio messages from the destroyers who were watching. Having learned that the “Goeben” is still leaving, he ordered the “Agamemnon” together with the “Foresight” and two destroyers not to go towards him, but to try to overtake the enemy. However, these respectable gentlemen managed to arrive at the battlefield when it was all over. Against the escaping “Gebena”, the British threw around 10 aircraft, which energetically and just as to no avail began to drop bombs. The water columns rose thickly around the battle cruiser until at the beginning of the eleventh the German fighters from Chanak pulled up to cover the air. In the ensuing air combat, one British aircraft was shot down, the other was damaged.

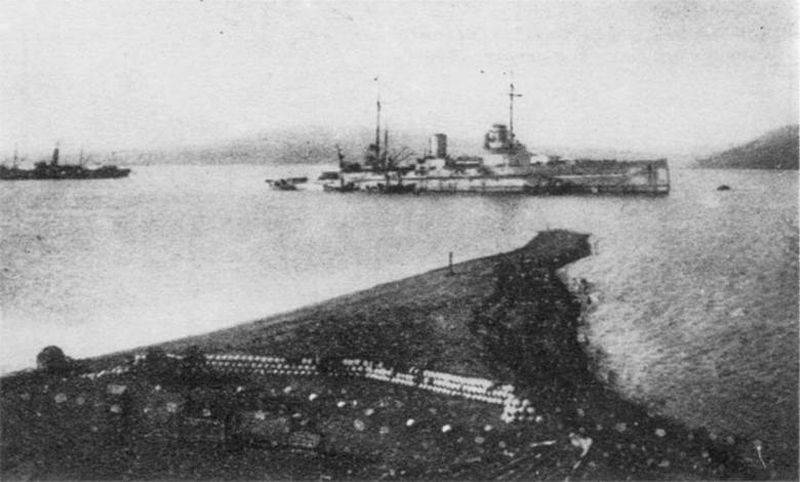

In 10 hours 30 minutes "Goeben" together with the destroyers accompanying him entered the Dardanelles. The operation is over. But the troubles are not over. At 11 hours, the ship overcame the last minefield, and the pilot was released. Having a lurch on the port side - the water still came inside the hull - the “Geben” reached Cape Nagara, where Shtenzel confused the buoys and gave the wrong order to the helmsman. On the 15-nodal speed, the battlecruiser stranded and got very hard on it.

On melody

The incident happened, like, in fact, many similar cases, at the most inopportune moment and in the same inappropriate place. The British had the opportunity to fire "Goeben" with cross-throw fire from the Gulf of Saros, attack with aviation. The first attempts to get aground on its own were not crowned with success - the sandy ground firmly held the ship. It was necessary to attract additional forces. All available submarine forces, including even old destroyers, were pulled to the Geben emergency site, the danger of the appearance of an enemy submarine, for which a stationary ship represented an excellent target, was considered very high. Anti-aircraft guns were also pulled up here, and fighters were installed at nearby airfields to repel air raids. To counteract possible shelling from the Saros Gulf, a correctional post was posted on the shore along with a senior artillery officer of Gebena. The fears of the Germans and Turks were not unfounded. On January 24, at night, the enemy fired from the bay. Judging by the ruptures, the shells belonged to 105-150 mm calibers — these were, according to observers, 2–3 destroyer-cruiser class ships. This fact forced rescue operations. It was clear that more serious guests would soon be welcome.

Another January 20 on the battle cruiser began to overload the ammunition from the bow to the stern, at the same time two 10-ton Admiralty anchors were wound up. The cars gave a “full back”, but the “Goben” did not budge. Attempts to use two tugs were also unsuccessful. In the evening of January 21, the old battleship Turgut Reis (former German battleship Weissenburg) arrived from Istanbul. According to experts, this 10-thousandth ship had a chance to move its larger brother from the sandbar. Meanwhile, the British threw bomber aircraft at Goben. The raids were very frequent, but ineffective. According to German estimates, at least 180 bombs were dropped on the battlecruiser, but only two landed on the ship. One hit damaged the chimney by making a hole in it about three meters. Another was in the mine network box. The time of the Lancaster and the five-ton Tollboys has not yet come. But the task of saving “Goeben” was very difficult even for “Turgut Reis” - having spent almost all of its coal in futile attempts to steal a battle cruiser, the battleship left for Istanbul to replenish its fuel reserves.

January 25 Turgut Reis is back. Now decided to do differently. The bottom consisted of sand. The battleship moored to the starboard "Goeben" - continuously working screws, he had to blur the sand bank. Turgut Reis machines worked all night, and in the morning on January 26, it was decided to try their luck. The battleship and several tugboats harnessed to the "Goeben" - his own cars gave a full turn back. However, the ship just turned on 13 degrees. This made it possible, nevertheless, to look at the situation optimistically - it was evident that the soil under the keel is loosened. Probes showed that the depth near the battlecruiser is gradually increasing. "Turgut Reis" again docked and continued to beat the water with screws. At about 16 hours, observers recorded a jet from its screws on the opposite side of the "Geben" - it was possible to wash the sand under the keel. A new attempt to grounded also was carried out by a whole group of vessels led by the old battleship. In 17 hours, the 47 minutes are so long and hard work, finally crowned with success. The Goeben got off the ground and immediately went to Istanbul.

Last of the battlecruisers

The Germans, of course, managed to make some noise. On 7 in the morning of January 20, English radio stations broadcast a message in plain text: all merchant ships east of Malta should immediately go to nearby ports in connection with the departure of the German squadron at sea. However, soon this instruction was canceled. The Admiralty removed from the post of Rear Admiral Hayes-Sadler, who so irresponsibly used the flagship for traveling (albeit official). The British fleet’s slap in the face of the long-awaited attack was received quite calmly - the outcome of the war was no longer in doubt.

Wrecked, but not sunk (the experts of the Blom and Foss shipyard knew their craft) “Goeben” did not go out to sea anymore - with the exception of one trip to Sevastopol occupied by German troops. There, the battleship repeatedly damaged, was finally repaired, which had not been known for nearly five years. Ironically, the Goeben stood in a dry dock intended for its sworn enemies — the dreadnoughts like the Empress Maria. The end of the repair almost coincided with the end of the war. Under the name Yavuz, a German veteran served in the Turkish fleet until the 60s. In the fire of the open-hearth furnaces, all of its soplavatel and opponents, representatives of the turbulent era of the dreadnought fever, the era of German-British rivalry, disappeared long ago. The old ship was laid up in jokes - even in Germany a company began to rescue the unique witness of the German naval power of the early 20th century. But politicians decided differently, and the career of the former “Goeben”, a ship with an amazing fate, ended up in 1973 with dismantling for scrap.

Information