Opposition of General Dragomirov: truth or fiction?

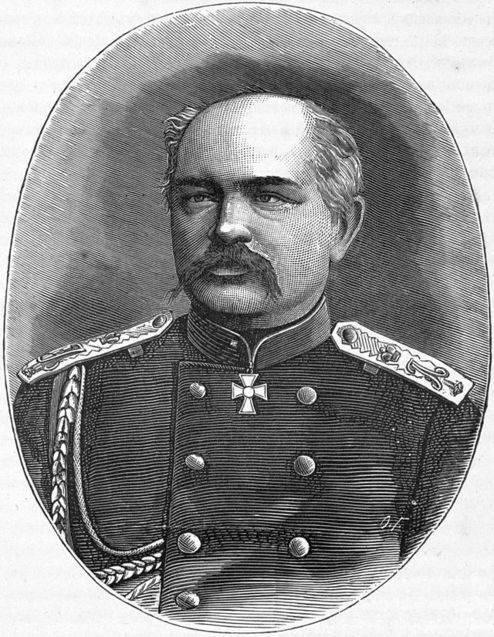

General Mikhail Ivanovich Dragomirov is known as a brilliant military theorist and hero of the Russian-Turkish war 1877-1878. Back in 1860-s. his articles riveted the attention of the public, and the lectures on tactics that he read at the Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff listened to the military youth with great interest. However, in February 1869, Mr. Dragomirov’s lecture turned out unexpectedly short: "Entering a younger classroom, he began the lecture ... but, having spoken several words with apparent excitement, went off to the blackboard and then 1-2 minutes, announcing to the audience, which, unfortunately, cannot continue lecturing, left the audience ... "1 The listening officers gathered at a break in the" smoking room "and learned that Dragomirov was forced to leave the academy. The reasons for this, obviously involuntary, abandonment of the department in the literature does not say. The official is silent about this story Academy. As it was succeeded to establish, Dragomirov was forced to leave the academy because of the reputation of a dangerous oppositionist.

"And you still keep me corrupting the army?"

It was precisely on opposition that General F. P. Rerberg, who in 1880-ies. became close to the family of Dragomirov and, most likely, learned the details from himself. Here is what he wrote in his memoirs: “Already from his youth, remarkable Mikhail Ivanovich suffered from the soul for the Russian army, finding that her education and upbringing were on the wrong track ... Having stayed in Petersburg, professor of the academy, Mikhail Ivanovich began writing on this issue and so boldly that once on the report of the Minister of War, the Emperor Alexander II deigned to say the following phrase: “Dragomirov corrupts the army with his writings!”. This word reached Dragomirov, but this self-righteous, persistent and courageous man continued to write After a while in the Winter Palace, on some occasion, there was a “way out.” When Emperor Alexander II, following in the head of the royal family, caught up with the group of the General Staff Academy, he stopped (which was almost never the case) and turning around to Mikhail Ivanovich, said: "Dragomirov! And you still continue to corrupt the army for me? "After this incident, everyone thought that the song of Dragomirov was sung. Dragomirov had to leave Petersburg." 2.

The administration of the academy was reinsured. “Colonel Tsiklinsky, a staff officer, arrived at the junior classroom and announced that the head of the academy recommends that M. Drahomirov be off-line with the officers of the entire course,” L. Drake recalled3. Obviously, they feared unnecessary demonstrations of disagreement with the dismissal of a popular professor.

So, Dragomirov had to leave the department and take the post of chief of staff of the Kiev military district. But where did the opinion of Dragomirov's views come from Alexander II? This question can be answered by the article of the professor.

"About probable changes in tactics"

Dragomirov's name began to appear in the military press immediately after the Crimean War 1853-1856, when there were heated discussions about the shortcomings of the military system of Nicholas I. Dragomirov actively criticized the traditions of Nikolai in the army, especially in training soldiers. A year before the forced transfer to Kiev, at the beginning of 1868, in the Military Collection, there was a discussion around his article "On probable changes in tactics due to the spread of distant and rapid-fire weapons". Formally, the article was highly specialized, but a careful reading of it shows that it contained something more than just talk about tactics.

The background of Drahomirov’s thoughts was a premonition of a new war: “Something feels alarming, as if it were inevitable before the disaster,” he wrote, “they all talk about the world mediocrely and at the same time arm themselves from head to toe. Apparently, one of those cataclysms that from time to time lead to the shaking of the human world and for not being ready for which they are severely punished ... "4 Russia’s unpreparedness for war caused the author’s great fears, and if his criticism is not heard, then" behind it, sooner or later but inevitably, another formidable will come I am criticism, criticism of the case, criticism, proving the groundlessness of one or the other direction in the formation of troops not by words, but by rivers of blood, tens of thousands of heads laid without glory and without benefits, sometimes even worse than that. ”5.

Having described the situation in such a grim way, Dragomirov attacked the old notions of the order, which survived the Nikolaev time and no longer corresponded to the new era. As before, as before the Crimean War, it was not the initiative and tactical training that was required of the troops, but “so that the back of the head is mathematical, the intervals and distances are correct up to a pitch” 6. It was in the overt and sharp criticism of the army order, and in the warning between the lines that the defeat in the Crimean War could be repeated, that the author threw to the military conservatives.

In the second issue of the Military Collection for 1868, Major General KI collapsed on the article. Gershelman, Assistant Chief of Staff of the St. Petersburg Military District. Gershelman accused Dragomirov of doctrinalism and that "the thoughts they set forth are no longer edification or advice, but a new teaching that passes imperceptibly and probably, apart from the authors' wishes, into some kind of opposition (singled out from Gershelman. - S.Yu.)" 7. So Dragomirov gained a reputation as an opposition figure.

Most likely, it was after this that Alexander II formed the opinion that Dragomirov "corrupts" the army by writing "opposition" articles, such as the article "On probable changes in tactics ...".

Undermining under the Minister of War

Similar accusations at that time were very serious. In 1866, the first attempt on the life of Alexander II took place. In the higher spheres, after the assassination attempt began, a lurch towards a more conservative course and intrigue against one of the pillars of the reform party - military minister D.A. Milutin. The unreliability of General Staff officers, their academies and professors was a trump card against the minister of war. The Nikolaev Academy worried the conservatives because S. Serakovsky, one of the leaders of the Polish uprising 1863, came out of its walls. In 1871, two years after Dragomirov’s dismissal, the academy received a new blow to reputation. At the reception, Alexander II addressed his chief, General A.N. Leontyev: “I now received a dispatch that Dombrovsky was appointed commander-in-chief of the commune in Paris! After all, was he our academy? Did you have him, Leontyev?” 8.

Heated the atmosphere and intensified in 1868-1869. student movement, which encompassed in addition to educational institutions under the jurisdiction of Milyutin Military Medical Academy9. The war ministry was exposed by reform opponents as a bastion of radicalism, and at the end of 1868, Milutin’s enemies succeeded in replacing the editor of the newspaper of the war ministry Russian Disabled. Friend Dragomirov Colonel S.P. Zykov was forced to give up his place to General PK, a more moderate editor. Menkovu. Not surprisingly, in his memoirs, Milyutin wrote: “All the troubles and sorrows I experienced at the end of the past [1868] year upset me both morally and physically, that I had already thought about leaving my post” 10.

Many years later, shortly before his death, General Dragomirov recalled that the "cute compatriots" defamed him "at one time, almost as a nihilist" 11. Surely such a reputation did not happen overnight, but the fact that it led to serious consequences precisely in 1868-1869 was not accidental. Most likely, the dragoms on Dragomirov were part of a campaign to discredit the Milutin ministry.

"Hegelist, Herzenist, Atheist and Political Liberal"

So was Dragomir’s oppositionist really? There is no doubt that he was not satisfied with the fundamentals of the military training system, but how far did his “opposition” reach? Determine it is not so easy.

First of all, almost the entire circle of military youth, in which Dragomirov rotated right after the Crimean War, was imbued with freedom-loving spirit. This was extremely typical for the entire generation that entered maturity in the 1850-1860s.

Gladly and hopefully having met the news of the death of Nicholas I, the young officers, yesterday's graduates of the academy, actively communicated with the civilians who were not very trustworthy, among whom were, for example, N.G. Chernyshevsky12. A classmate of Dragomirov recalled that when he went to the apartment of one of the headquarters officers of the Academy, he saw two portraits and the question "Who is this?" I heard, “Don't you know? It's Herzen and Ogarev.” 13. Dragomirov himself at the beginning of the 1850's. there was "a hegelist, Herzenist, atheist, and political liberal," who "distributes secretly Herzen's handwritten articles, the book of Radishchev, and so on." 14. It is noteworthy that the officer of the General Staff, MI. Venyukov, who left this testimony, himself wrote in Herzen's “Bell” and even translated “Marseillaise” into Russian. In short, the government had reason to doubt the credibility of many General Staff officers, including Dragomirov.

But since then, many years have passed and even more events. The reforms of the government of Alexander II and especially the Polish uprising 1863 g. Became a certain watershed, forcing many to abandon political radicalism. Venyukov, who calls Dragomirov a “political liberal,” portrays him in his memoirs as a renegade who later made his career without regard to the ideals of youth. One can hardly imagine that the mature Dragomirov, who was already 1869 years old in 38, kept opposition moods. The words of the General are well known, which he said in 1884, after the arrest of a student of the Academy N.M. Rogachev, associated with the People. “I am talking to you as people who have to have their own convictions,” Dragomirov addressed the audience. “You can enter any political parties you like. But before you do, remove your uniform. You can’t simultaneously serve your king and his enemies.” 15 .

General A.S. Lukomsky, who knew Dragomirov closely in the 1890-1900-s, characterized his political views as follows: "Dragomirov was a supporter of progress, and he linked this with the wide provision of opportunities for people to identify their talents and develop. He was an ardent supporter of the reforms carried out during the reign Emperor Alexander II. But at the same time he was a prominent representative of the current, seeing the need for a firm and uncompromising royal power "16.

So, Dragomirov, who did not agree with some tendencies in the military sphere, was hardly an oppositionist in 1869 in the full sense of the word. Needless to say, at the moment of exile from the academy he was in political opposition to the government. Reputation did not match reality.

Aftermath

Despite the fact that the academic authorities forbade the disgraced professor to see off, the listeners sent a small delegation to Nikolaevsky station17. After his retirement from the academy, Dragomirov took the post of chief of staff of the Kiev Military District. Until 1872, that is, for almost three years, the name of the general did not appear on the pages of the military press. Unfortunately, it is not known whether he was excommunicated from the press or whether he himself decided to take a break. His service was as usual. He continued to receive rewards and favors and was even enrolled at 1872 in the imperial retinue of 18.

Russian-Turkish war 1877-1878 brought Dragomir's laurels. He brilliantly prepared his 14 Infantry Division for it and successfully carried out the operation to force the Danube. The war in the Balkans not only rehabilitated him, but raised him to the height of one of the main Russian military authorities both in public opinion and in the opinion of Emperor Alexander II. "The war ends, and the same Dragomirov, who" dared "to write, neglecting the views of both the sovereign and the sovereign closest ones,” noted FP Rerberg, “is awarded with two George, the rank of adjutant general, entrusted to education and upbringing of the entire Russian General Staff and finally entrusted to him the direction of the future sovereign’s thoughts (Dragomirov became one of the future teachers of Nicholas II. - C.Yu.) "19.

In the end, the story of the article "On probable changes in tactics ..." and the subsequent removal of Dragomirov from St. Petersburg remained only sad episodes in a brilliantly established career that crowned the authorities over the troops of the Kiev Military District and the Governor-General in the South-Western Territory. Dragomirov went through a political evolution that was typical of his generation: from the radicalism of the 1850s. to moderate and trustworthy views in the late 1860-e. But the opposition "trail" stretched behind him, as well as some other people from the circles of the General Staff, and could be used by opponents of the general. It was often easier to blame the criticism for opposition than to respond to criticism. Dragomirov’s departure from the pulpit and from the pages of military journals was a victory for opponents of his ideas. But a temporary victory.

Notes

1. D [rake] L. Outlines from the past. Fragmentary memories 1868-1874's // Military-historical collection. 1912. N 1. C. 63.

2. House of Russian Abroad them. A.I. Solzhenitsyn (DRZ) F. 2. M-86 (KN.1). L. 158.

3. D [rake] L. Decree. cit. C. 63.

4. D [ragomirov] About probable changes in tactics, due to the proliferation of distant and rapid-fire weapons // Military collection (VS). 1867. N 11. C. 3.

5. D [ragomir]. About probable changes ... // BC. 1867. N 12. C. 188.

6. Ibid. C. 179.

7. Herschelman. A few words about the modern direction of some of our writers on tactics // Sun. 1868. 1. C. 4.

8. D [rake] L. Outlines from the past. Fragmentary memories 1868-1874's // Military-historical collection. 1912. N 1. C.66.

9. Svatikov S.G. Student movement 1869 of the year (Bakunin and Nechaev) // Our country. Historical collection. SPb., 1907. C. 182-197.

10. Milyutin D.A. Memories. 1868 is the beginning of 1873. M., 2006. C. 145.

11. Dragomirov M. Theoretical Foundations of the Education and Formation of Troops // Scout. 1901. N 574. C. 926.

12. Ayrapetov О.R. Forgotten career "Russian Moltke": Nikolai Nikolayevich Obruchev (1830-1904). SPb., 1998. C. 52-53, 56-57.

13. Zalesov N.G. Notes N.G. Zalesov // Russian antiquity. 1903. July. T. 115. C. 32.

14. Venyukov M.I. From the memoirs of M.I. Venyukova. 1 Book: 1832-1867. Amsterdam, 1895. C. 63.

15. Denikin A.I. The path of the Russian officer. M., 2014. C. 74.

16. Lukomsky A.S. Essays from my life. Memories. M., 2012. C. 129.

17. D [rake] L. Decree. cit. C. 63.

18. RGVIA.F. 489. Op.1. D. 7106. L. 841-853, 854-861.

19. DRZ.F. 2. M-86 (KN.1). L. 159.

Information