Royal travel to the Caucasus

From Catherine's time, the Russian monarchs from time to time left St. Petersburg, embarking on a journey through a subservient empire. Several times the ruling rulers and members of the royal family visited the Caucasus. The goals of these voyages were multifaceted. The highest concern for the provinces of the empire was demonstrated, the appearance of the emperor's union with loyal subjects was created, the detour of the subordinate lands signified the primacy of Russia over them, and acquaintance with remote regions gave royal travelers new knowledge and impressions about the state they ruled. Sometimes, in a difficult political situation, the personal presence of the monarch and the explanations of important issues emanating from him turned out to be expedient.

"From the mouth of his beloved monarch"

A trip to the Caucasus in 1861 g was especially crucial for Alexander II. The time and place were significant: the Crimean War was recently lost, the Caucasian War was nearing completion, and the peasant reform began. The emperor met with representatives of the mountain peoples, listened to their vision of the situation and outlined his own. In Kutaisi, almost all the nobles of Transcaucasia gathered to meet him. Alexander addressed them with a speech about the meaning of the February 18 Manifesto, about the goals and methods of the abolition of serfdom. "The nobility of Christian Georgia, Imeretia, Mingrelia and Guria and the Mohammedan provinces of the region, having heard from the lips of their beloved monarch the need to submit to them already perfect reform in Russia, unquestioningly and with complete readiness began the cause of liberating the peasants" 1.

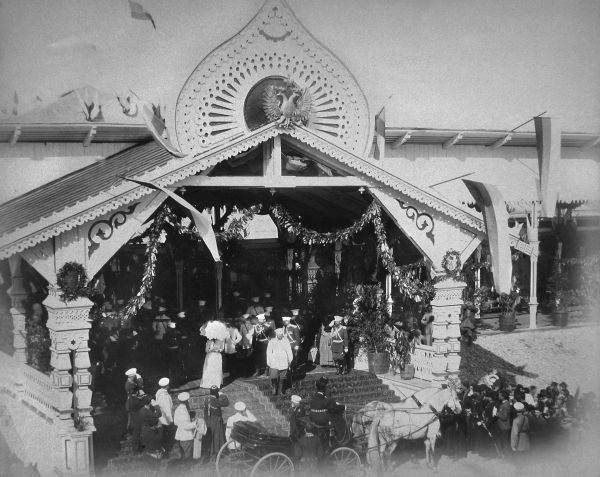

The Russian command carefully prepared and prepared the locals for the meeting of the royal travelers, trying to demonstrate both their administrative achievements and the exotic of the Caucasus. It was believed that to accept the rulers of the empire who had come to the edge of the empire, “natives” were appropriate in national clothes and in the traditional weapons. The Highlanders did not mind. They put on Circassian, cap and other ethnic paraphernalia. When Alexander III and his family drove along the Georgian mountain region of Khevsureti in 1888, he admired fifty of the horse-riding Khevsurs in ancient chain mail and helmets with shields and spears; women in embroidered patterned robes came out to the road. In Baku, a system of Turkmen and Kyrgyz appeared before him, whose "colorful costumes, high hats, tanned courageous faces attracted attention" 2. The present performance met the imperial couple of Tiflis. Already at the railway station, the emperor with his wife and sons saw the slender ranks of the townspeople. Thirty young Georgians from noble families in colorful national costumes stretched out in a line. The picturesque picture was presented by an amkar (craft corporation) of gunsmiths, dressed in ancient armor with shields, halberds, maces and swords. Behind him stood an amkar of hat-makers in the same huge merlushkovye hats, with bouquets in their hands, then tanners in the same yellow clothes, belted in colorful shawls, stood3. Exotic "uniforms" emphasized the staged action.

Almost in all large settlements, through which the routes of the voyages ran, meetings with the population were arranged. Their mandatory element was the participation of representatives of local peoples. Together with the officials and officers of the units quartered there, they were called upon to personify cohesion around the monarch and prosperity under the shadow of his rule. The absolute majority of such events were limited to the presentation of senior officials and the social elite of indigenous peoples, the monarch's protocol phrases about his gracious attitude and gratitude for his devotion. Sometimes greetings and poetic odes were read, gifts from the emperor and offerings from guests were presented. The combination of multi-color national costumes and multilingual speeches created a vivid picture of poly-ethnicity and indirectly - the vastness and power of Russia.

"The hunt is over and a deer is captured"

During trips to the Caucasus for travelers invented special entertainment. In Mingrelia for Alexander II, a battled deer hunt was arranged. At that time, the hunters had no luck - the animals hid. In order not to leave the emperor without a trophy, the organizer of the event, the "native" prince, sent his own hand-made deer to a raid. However, he did not rush to run, but calmly stood still and looked at people. Alexander, of course, did not kill him, but approached and stroked with the words: "The hunt is over, and a deer is captured" 4. In the same place, in the Mingrelian mountains, the emperor had a chance to taste an amazing treat, about which the memories of eyewitnesses remained. At breakfast, prepared a dish called the author of the XIX century. barbecue monster, although it was not kebab in the modern sense. "Four tall mingrelts are brought to the king of a whole bull roasted on a spit," cutting it out, take it out from inside the calf, from the calf of the lamb, from this turkey, from the turkey - chicken, and from it the thrush, and all this is seasoned with artistically tasty "5.

During the trips of members of the imperial family in the country, the mixed ethnic subjects of the empire had the opportunity to talk about their people, their customs and way of life, to demonstrate the art of local craftsmen and devotion to the monarch. Expanding this kind of knowledge to the imperial family could be the most obvious way: to present them with the products of local handicrafts, household items and religious non-Orthodox cult, as well as products with informative ethnic symbols. For high-ranking guests, "demonstration performances" were organized in order to acquaint them with folk customs and amusements - the most august audience was taught a veiled ethnographic lesson.

Plucked rooster for the emperor

Not a single royal journey through the regions of the empire was complete without offerings. Everywhere greeting was expressed in the presentation of bread and salt. Only Kalmyks and Buryats, without violating their custom, were given instead white silk scarves, Khadaki. In 1888, Alexander III and Maria Fedorovna and their household in Baku received expressions of loyalty from the peoples of the Caucasus and the Central Asian Caspian. Dagestanis brought the emperor bread and salt and a black burqa, the empress brought a white burka, a hood and two pieces of camel wool, and the Turkmen gave her eight Tekin carpets. The Dagestanis presented the sons of the emperor Nikolay and George with a sheath in a sheath from a black horn and a dagger, and the Turkmen - a precious saber repulsed by Tekians in a battle with a Persian prince.

In Vladikavkaz, travelers were met by representatives of "loyal subjects of Kabardian and highland tribes". The emperor deigned to take the Kabardian silver saddle with a mob, the empress - a rich Kabardian costume with a crown cap, Nikolai - relics of noble Kabardian clans: the family cap of Atazhukins princes, a gun from Kudenetovs (noblemen) Kudenetovs and an ancient Arab dagger. Bread and salt were delivered from the Chechens on a dish framed in silver and silver salt shaker, a gun, a sword and a burqa, the empress received a burka with a hood, Nikolai - a dagger on a belt, George - a burka; from the Ingush: the emperor brought bread and salt on a silver platter, the empress - the burka; from Ossetians - bread and salt on a golden table; from Karanogayans and Mountain Jews - bread and salt on silver dishes and many steel and chased products6.

In Elizavetpol, a meeting was held with the Karabakh khansha, who bowed to the emperor with a carpet, the empress with a gold-embroidered cape, and Nikolay with a woolen blanket7.

When traveling around the southern regions of a boundless power, Russian autocrats sometimes had to come into contact with the allegorical wisdom of the East, embodied in unusual offerings. In October, 1837 in the Sardarabad fortress Nikolay I decided to listen to complaints about abuses of local authorities. Among the petitioners was an Armenian who did not know a word in Russian, but wanted to convey to the sovereign the truth about the plight of the local inhabitants. To this end, he presented the emperor with a vivid illustration of his silent story - a skinny plucked rooster as the personification of poverty and deprivation of the Sardarabad people. “Such means and for the same purpose,” writes the author of the story about this case, AP Berger, “were resorted to in other places along the path of the highest passage.” In Erivan, the emperor dined in the palace of Serdar, the former ruler of the Khanate. From the street came the cries: "Arzymyz var, co-imierler!" (we have petitions, but are not allowed). Caucasian commander G.V. Rosen explained that these are de cries of delight on the occasion of the arrival of the Russian Padishah. Nikolai did not believe and sent to understand the head of his office. He returned with a pile of 8 requests.

His Majesty's Security

Emperors in the Caucasus were at considerable risk. But Nicholas I, driving through the region in 1837, at the height of the Caucasian War, was satisfied with his guards and convoys. There were shifts consisting of Turks, Armenians, highlanders. They were awarded specially minted medals, and upon returning to the capital, the emperor issued a decree that obliged the Caucasian command to send a Caucasian half-squadron, created ten years before, by 12 a man from noble mountain families to the Life Guards. Nicholas I decided that people who showed unlimited devotion in a risky atmosphere would be equally reliable in the guard service.

He also ordered to accept to study in the Noble regiment of the mountain young men. They had to be in foreign lands, surrounded by "infidel" peers. Chief of the III Division of His Own Imperial Majesty's Office, Count A.Kh. Benkendorf compiled instructions for the personnel of this military school and for Russian cadets. They had to Caucasians-Muslims "not to give pork and ham, strictly forbid the ridicule of nobles and try to make friends of the mountaineers with them ... Not corporal punishments (mountaineers. - V.T.), generally punish only through the mediation of Ensign Tuganov, who is better off what people know how to handle "9. Nevertheless, almost none of the Kabardian and Balkarian nobility agreed to send their sons to study in St. Petersburg. Mountain aristocrats feared that their offspring far from home would forget their native language and customs. But so that the authorities did not see in such a refusal a boycott of government policy, it was decided to send the children of the minor nobility Uznews 10 to the training.

Alexander II during the detour of the North Caucasus was accompanied not only by the Cossacks and the Russian militia, but also by the Kabardian princes with knots. Driving through the territory of Chechnya, Alexander watched as the "huge crowd of Chechens" famously dzhigitoval along the way of his following. More than a thousand of them made up the royal convoy in the Terek region11. The emperor did not feel any negative mood. His inaccessible sacral persona, like the image of any sovereign, instilled in the highlanders superstitious respect. On the day of his arrival at the Chechen aul of Vedeno 14 in September 1871 was born into a family of one local resident twins. Impressed by the momentous event, the father gave them the names Alexander and Mikhail (in honor of the emperor and his brother - the Caucasian governor-general) 12.

It seems that the genre of the royal journey and its ceremonial flow excluded any conflict situations. The real danger could lie in wait for the kings of the voyage except during the war with the mountaineers. Most of the Chechens and the peoples of the mountainous Dagestan then united around Imam Shamil and waged a fierce struggle with the Russian troops. Contacts with the mountain deputations caused alarm among escort officers carrying guards. In 1826, during one of these meetings, the generals Grekov and Lisanevich were slaughtered by a Chechen participant in the negotiations. Therefore, Nicholas I in Vladikavkaz in 1837 was urged not to risk communicating with the local population. "It's all nonsense!" - answered the king and the next day fearlessly stepped into the crowd of three hundred mountain deputies, representatives of the "tribes of the left flank." He ordered them to spread everywhere his order to stop the predatory attacks on Cossack villages. Then the emperor approached the Karabulak Vainakhs standing separately, chose a fierce-looking giant with a long dagger, put a hand on his shoulder and told the translator: "Tell this people that they are behaving badly and that they continue as I feel good towards them tried to correct as soon as possible. " The elder Karabulak timidly said that they were afraid of a possible compulsion to change their faith. Nikolai pointed to his mountain convoy: "I have all the faiths tolerated, and now your children can tell you that they have a mullah in St. Petersburg" 13.

Another memoirist talks about meeting with Caucasians differently. At the reception of the mountain deputations, the emperor was irritated by the mountaineers, who did not want to submit, was fully expressed. He “spoke very favorably with all the representatives of the nations, excluding from this the ill-fated Chechens, whom he reproached with infidelity to him and his Russian laws. They answered that they were in fact loyal to the sovereign and were ready to abide by his laws, but the outrage of the Russian authorities in the Caucasus caused their indignation. Then they tried to file a petition to Nicholas outlining this situation. The emperor became angry, called everything said by the Chechens slander and ordered them to "get rid of the bad thoughts inspired by unreliable people" by 14. It is clear that the Chechen petition remained without consequences, and the war continued after that for many more years.

Both courage and diplomacy

A truly risky situation developed during a visit to the Caucasus by Tsarevich Alexander Nikolayevich in the autumn of 1850. The future great reformer passed through the environs of the Chechen aul Urus-Martan under the protection of the faithful Cossacks. In the distance riders appeared in recognizable clothes. Swept the cry: "Chechens!" 32 years old Alexander rode in that direction, and the whole retinue rushed after him. Even the then Caucasian governor, Prince MS Vorontsov, who, because of his old age and poor health, was carried in the carriage, fearing responsibility, mounted his horse and rushed after the crown prince. The Cossacks with victorious shouts and with their swords naked flew into the attack, two field guns from the convoy deployed in the direction of the enemy and fired shot. The Chechens did not expect such a pressure and rode away, leaving one dead and several horses. Mikhail Vorontsov, who offered prayers to ensure that nothing happened to the heir to the throne, introduced Alexander Nikolayevich to the Order of St. George15.

Alexander II had to clarify relations with the peoples of the Caucasus in 1861. At that time the war in Chechnya and Dagestan had already ended, but the fighting continued in the north-west of the region, in the lands of the Circassians. In the minds of generals and officials, a plan was ripened for the eviction of the rebellious natives into the Ottoman Empire. Already on the border of the Caucasian governorate, in Taman, the emperor was met by a deputation of five hundred Circassians. As he approached, they all laid down their arms on the ground, bowed, and their elder petitioned: his fellow tribesmen would be the best and most loyal subjects, would build roads and fortresses for the Russian troops, just to stay at home. Alexander promised to do everything possible for this, and the Circassians with joyful exclamations moved in a crowd to escort him 16.

An evasive response was obviously a diplomatic ploy in the dangerous surroundings of the armed highlanders. Both the emperor and the influential part of the ruling elite decided to radically end the Adyghe problem by forcing hundreds of thousands of indigenous people of the North-West Caucasus to emigrate. Later Alexander did not promise anything to the Adygs, but kept himself with them more and more strictly. At a similar meeting in the Zakuban Nizhnefarsk detachment, the Highlanders attempted to suggest the terms of their reconciliation with the Russians. Alexander did not want to listen to them. If they brought him unconditional obedience, he said, then he accepts it, and if they have any conditions, then let them tell General N.I. Evdokimov17. He quickly turned and left. The Circassians did not go to the general, but exchanging impressions gloomily, mounted their horses and left 18.

Once again the emperor had a chance to meet with the highlanders on this issue in the Upper Abadzekh detachment. Adygs prepared for the meeting, formulated the conditions for ending the war. Nevertheless, after the end of the parade of Russian troops, about fifty representatives of the Adyg tribes (Abadzekhs, Shapsugs, Ubykhs) in ceremonial medieval armor headed towards the emperor. They were forced to dismount, disarm, and only after that they were allowed to him. After hearing their speeches, Alexander said that within a month the Circassians should decide: either move inland to the places indicated by the authorities, or leave for the Turks. A month later, the army will resume hostilities and force them to do both. This response of some Highlanders was dismayed, others - infuriated. In their camp, fights with stabbings began, hundreds of horsemen rushed along the plain with a whoopie and fired into the air. True, less than two versts they did not approach the Russian location - from there the guns were directed at them. The old men barely calmed the rampaging youth of 19.

During the movements of the autocrats in the country, a lot of attention was paid to their security. Security was organized carefully, and there were usually no disturbing situations. Yes, and the internal political situation in the empire to 1870. remained calm. It was only when the popular terror with its culmination — the murder of Alexander II — turned around, that the attitude to such trips had to be reconsidered. They almost stopped. Tsarevich Nikolai Alexandrovich never completed his education cycle with an informative trip around Russia, but instead went to far eastern countries (although he returned to St. Petersburg from Japan through all of Siberia).

Notes

1 Shcherbakov A. Imperator Alexander II in the Caucasus in 1861 year // Russian antiquity. 1883. T. XL.S. 381.

2. Notes on the journey of His Majesty the Emperor in the Terek region // Terek Gazette. 1871. 15 October. N 42. C. 2; Stay in the Caucasus in 1888 of their Imperial Majesties, Emperor Alexander III Aleksandrovich and Empress Maria Feodorovna // The Caucasian calendar for 1889 year. Application. Tiflis, 1888. C. 54, 57; Journey of their imperial majesties // Moscow Gazette. 1888. 13 October. N 284. C. 3.

3. Staying in the Caucasus in 1888 of their imperial majesties. C. 33, 34.

4. Shcherbakov A. Imperator Alexander II in the Caucasus. C. 386, 387.

5. Ibid. S. 389.

6. Staying in the Caucasus in 1888 of their imperial majesties. C. 10-12, 68.

7. Ibid. S. 72.

8. Berge A.P. Emperor Nicholas in the Caucasus in 1837. // Russian antiquity. 1884. T. 43. August. C. 382, 385.

9. Vyskochkov L.V. Weekdays and holidays of the imperial court. SPb., 2012. C. 121-123. Tuganov was an Ossetian.

10. Close. Letters from the North Caucasus. V // Caspian. 1903. 6 November. C. 3.

11. Notes on the journey of His Majesty the Emperor in the Terek region // Terek Gazette. 1871. 1 October. N 40. C. 2, 3; 8 October. N 41. C. 2; 15 October. N 42. C. 2, 3.

12. They write to us from Vedeno // Terek Gazette. 1871. 15 October. N 42. C. 3.

13. I. Shlykov. From the memories of the stay in the Caucasus of Emperor Nicholas I in 1837 // Terskie Vedomosti. 1888. 20 November. C. 3.

14. Kunduhov M. Memoirs. http://aul.narod.ru/Memuary_gen_Musa-Pashi_Kunduhova.html

15. Olshevsky M.Ya. Tsarevich Alexander Nikolaevich in the Caucasus from September 12 to October 28 1850 // Russian Antiquity. 1884. T. 43. September. C. 586.

16. Emperor Alexander II among non-peaceful Circassians // Kuban regional sheets. 1900. 27 January. C. 2.

17. Lieutenant-General N.I. Evdokimov - commander of the Kuban region, one of the initiators of the eviction of the Circassians to Turkey.

18. Bentkovsky I.V. Emperor Alexander II in the Nizhnefarsk detachment, in the North-West Caucasus, in 1861 year. SPb., 1887. C. 10, 11.

19. Olshevsky M.Ya. Emperor Alexander Nikolaevich in the Western Caucasus in 1861 year // Russian antiquity. 1884. T. 41-42. May. C. 365, 370, 372; Report of the Tiflis Governor General Lieutenant General GD Orbeliani to the military minister lieutenant-general D.A. Milyutin on the situation in the Western Caucasus and the meeting of Alexander II with the delegations of the Circassian tribes of Abadzekhs, Ubykhs and Shapsugs in the camp of the Upper Abadzinsky detachment // Relocation of Circassians to the Ottoman Empire according to documents of the Russian archives. 1860-1865. October 7 1861 g. Http://kavkaz.rusarchives.ru/1861god.html.

Information