Pull the rope!

It is considered to be. that for the whole XVIII century nothing fundamentally new appeared in artillery, and that the armats of the Northern War practically did not differ from the guns of the times of Borodin and Waterloo. Regarding field artillery, this is generally true, but in naval - Something interesting did happen.

In 1745, in England, an artillery flintlock was patented, and after some time, the production of naval guns with such locks was established. The importance of this invention lay in the fact that when firing from wick ignition guns standing on the lower decks of battleships and frigates, the gunner could not see where he was shooting at. He had to be on the side of the gun so that he would not be crippled by a rollback, and it was impossible to look at the gun port from this position.

Accordingly, the gunner could not accurately calculate the time of the shot. When firing at relatively large (by then standards) distances in rolling conditions, this often led to misses. The cores either whistled over the enemy ship, or were buried in the water with undershoot.

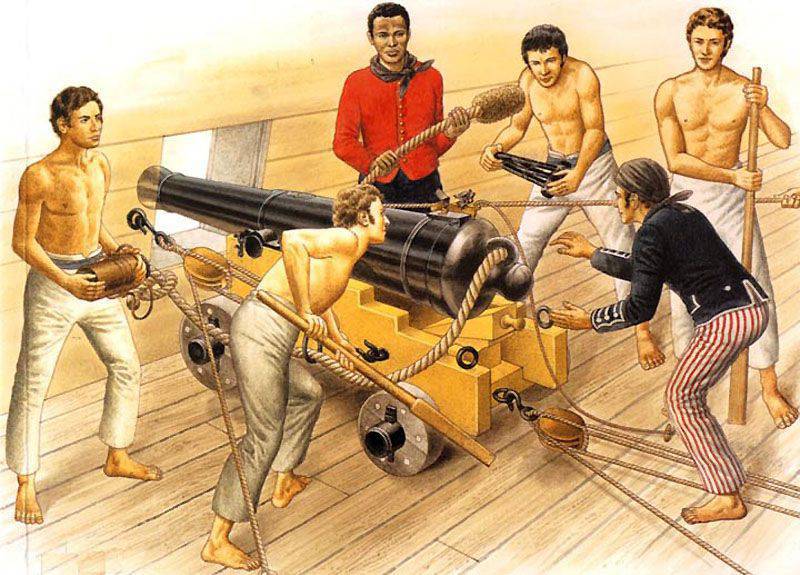

And the flintlock was pulled down by a long rope. In this case, the gunner could stand behind the gun at a safe distance, look at the target through the embrasure and produce a shot at exactly the right moment.

By the beginning of the 19th century, all British battleships being commissioned were equipped with flint tools, and much of the old ships, including the famous Victory Nelson, were equipped with them during repairs and upgrades. However, in other countries, the introduction of new items was much slower. Even under Trafalgar, almost the entire French fleet was armed with wicker artillery, and in Russia the production of flintlock gun locks in English style began even later - in the 20-s of the XIX century.

The fleets of secondary naval powers, this "high tech" generally bypassed, wick guns were used there until the appearance of blasting trigger mechanisms.

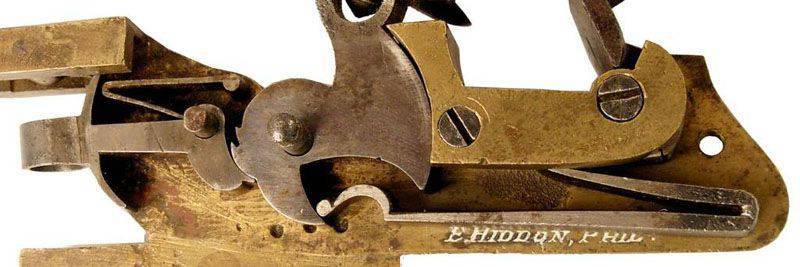

Flintlock gun locks of various designs, made in the last quarter of the XVIII and the first half of the XIX century.

The mechanism of a flintlock gun, the trigger is lowered.

Guns with flint locks on the battery deck of the battleship Victory. The release cords wrapped around the locks.

The gun on the upper deck of the same battleship. For protection from sea water and precipitation, the lock is covered with a tin casing.

[/ Center]

[/ Center]English (above) and Russian (below) flintlock gun locks. It is clearly seen that the Russian mechanism, made in Tula in the 1836 year, is almost an exact copy of English.

A replica of the Russian carronades of the XIX century with a flintlock.

Information