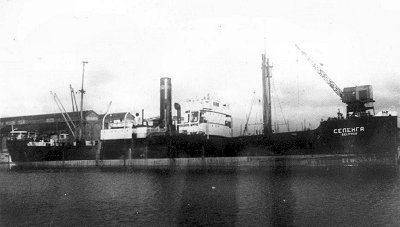

Capture of the Selenga steamer

In October 1939, the Soviet ship Selenga left Vladivostok and headed for the Philippines. The transition passed without any complications, and on October 25 the ship was anchored in Manila’s internal roadstead. Having barely finished the parish, we started loading. From both sides they moored along the lighter, from which tungsten and molybdenum ore and 1600 t coffee began to flow into the holds of the Selenga. After that, on November 5, the ship sailed to Vladivostok.

While the Soviet ship was stationed in Manila, local newspapers vied with each other that the Selenga accepted valuable strategic cargo, which would probably be sent from Vladivostok to Germany by the Trans-Siberian Railway, but it is unlikely that British warships on the roads will allow it. These articles were provocative in nature, but the crew was not particularly worried.

The next day, sailing, on the approach to the island of Formosa (Taiwan), the vessel caught up with the British cruiser Liverpool. A “Immediately stop!” Signal was fluttering on his mast. This was a gross violation of the freedom of navigation on the high seas. Therefore, the captain of the "Selenga" Alexey Pavlovich Yaskevich did not begin to fulfill the order and ordered to follow the previous course. On the cruiser, they uncovered the guns and went towards rapprochement. A motorboat was launched from the cruiser. A few minutes later he was already there, and the naval sailors who had gathered in him did not have the special difficulty of “boarding” the Soviet low-breasted ship. He headed the landing, as it soon became clear, the senior assistant commander of the ship. The British quickly scattered on the ship.

However, the radio operator "Selenga" has already managed to transfer to Vladivostok, that the ship was detained by an English cruiser and that the military team is coming aboard. Nothing more could not be reported, the British broke into the radio room. At the same time they appeared on the bridge.

The English officer announced that, according to their information, the cargo of tungsten and molybdenum on board the Selenga was intended for Germany, with which England was in a state of war. Therefore, he was instructed to detain the vessel and take him to Hong Kong to inspect cargo and shipping documents. Yaskevich protested, stressing that the Soviet Union was not at war with anyone, and the British seized the ship of a neutral power. However, the English officer demanded to follow to Hong Kong to verify information regarding the cargo. It was clear that the decision was made much earlier, and any arguments are simply not taken into account. "We will not play hide-and-seek, captain," the officer finally said in response to a categorical refusal to go to Hong Kong, "if you do not obey, I have an order to force the entire crew to the cruiser, and we will take the vessel in tow."

A.P. Yaskevich understood that to leave the vessel without a crew is impossible in any case - any new provocation is possible. Therefore, submitting to force, he led the Selenga to Hong Kong under the escort of a cruiser. On board the ship, the British left three officers and forty armed sailors. 12 on November the ship was anchored in the military port of Hong Kong, and the sailors from the cruiser were replaced by naval police.

Soon the commission arrived, headed by the head of the naval base, who announced that before finding out whether the cargo was “Selenga”, it was arrested, but the crew has the right to go ashore. After that the holds were opened, the cargo was photographed and copies were taken of the shipping documents. Having completed this work and sealed the radio room, the commission departed.

The next day, the captain of the ship went ashore, sought out a representative of Exportles in the city and through him sent telegrams about the detention of the ship to the head of the Far Eastern Shipping Company and the ambassador of the Soviet Union in England. For the team stretched days of anxious waiting.

Protracted flight, tropical climate, nervous tension did their job. By the end of the month, three crew members were sick. They were able to be sent to Vladivostok on a Norwegian vessel en route with a load of tea. With them, Yaskevich delivered a detailed report on the incident to the address of the head of the shipping company. In addition, he asked to solve a number of problems related to the payment of money to the crew, the costs of products, materials, bunker and other practical issues that inevitably arise in unforeseen circumstances. The answer was required to give on the radio in the agreed time, without confirming receipt.

By this time, managed to convince the British that the crew can no longer without a radio. It really was like this: people didn’t have enough news from the Motherland, simple Russian speech, music. But now the receiver was especially needed to accept the shipping company's response. With the consent of the watchmen, the radio was moved from the radio room to the mess room. Near him the crew set the duty. About a month after the patients were sent, the radio operator was able to listen to the shipping company’s answers.

Meanwhile, life went on as usual. The crew maintained the vessel in the proper form, carried out repair work. The monotonous series of days is occasionally interrupted by "entertainment." Once a Chinese arrived on the ship, introduced by a representative of a Hong Kong shipowner. Having handed over a business card, he said that he had instructions to talk with the captain about the sale of the vessel and cargo. According to the information that his firm allegedly has, the British are not going to release the Selenga. The price and terms of sale can be negotiated later, in a relaxed atmosphere in one of the restaurants in the mainland of Hong Kong. Yaskevich suspected that the meeting was inspired by the British authorities. Unless could this type get on the vessel without their permission? To avoid trouble, the captain decided to consult with our representative in Hong Kong, and appointed the meeting to the Chinese after three days. As expected, the “buyer” did not appear at the appointed time. And through our representative, it was established that the company was not listed on any list of Hong Kong firms.

There was another case. Once a Russian émigré appeared on the ship, identifying himself as Popov. He arrived on a junk in the form of a junior officer of the English maritime police. The officers on duty on the ship missed him unhindered. Mercilessly cursing England and the British, this Popov, in great secrecy, said that the ship would soon be released and asked to hide him on the ship to return to the Soviet Union. It was the simplest attempt of provocation, calculated to accuse the Soviet sailors in violation of local laws. The capital gave the command to throw Popov into the junk that stood at the ramp. Police officers on duty on the ship silently watched this scene and did not even intervene.

12 January 1940, two months after the arrest of the vessel, the commander of the naval base arrived at it. He told the captain that, according to the instructions from London, the Selenga is being released, and you can prepare to leave for Vladivostok.

On January 14 the ship was completely ready to go. The last formality remained — to receive from the port authorities a special flag signal for the passage of the port gate and the side fence. Yaskevich was informed that the signal would be given directly by the chief of the naval base, who would arrive on the ship especially for this.

He really arrived in the afternoon, but not alone: he had a French naval officer with him. The Englishman confirmed once again that his authorities were releasing the ship. But the allies of England, the French, have some questions. So he left.

History repeated. The Frenchman was the senior assistant to the commander of the auxiliary cruiser Aramis. More recently, it was a large passenger vessel of the company Messager Maritime, re-equipped with the beginning of the war, and became part of the French Asiatic squadron. Now the cruiser was on the roads near our ship.

Having put forward all the same absurd claims regarding the cargo, the officer announced that the French authorities were detaining the Selenga and offering to accompany the cruiser to Saigon. After Yaskevich refused to execute the instructions of the French officer to board the Selenga, two motor boats with Aramis, packed with armed sailors, rushed. Having unceremoniously disembarked the ship, they first occupied the bridge, then the engine room and all the rooms of the ship. The captain of the Soviet ship was again asked to sail to Saigon. In case of refusal, the entire crew will be transferred to the cruiser and placed under arrest, and the Selenga steamer in tow will be delivered to Saigon.

Strongly refusing to fulfill this requirement, appealing illegal actions, A.P. Yaskevich demanded to remove all the French from the ship. In response, armed French sailors, at the command of an officer, began to force, or rather, demolish, on the hands of resisting crew members and commanders, cruisers standing at the side of the boat. But the captain had already foreseen this, so he managed in advance to convey instructions to the senior mechanic so that in the event of which the French could not lead the Selenga on their own.

On the "Selenga" were alone the French. On the cruiser, the whole team was driven into one cabin, and the command personnel was placed in cabins. All premises have sentries. So, before receiving instructions from France, the crew had to be in the position of internment. First - on board the Aramis, and then on the coast - under the supervision of the French colonial authorities. The situation was complicated by the fact that the USSR did not know anything about the next events at the Selenga, so quickly events developed.

When the convoy brought the crew of the vessel to the upper deck for a walk the next morning, the Soviet sailors saw the Selenga, walking alongside the cruiser. The ship was moving barely. This meant that the senior mechanic had time to disable the water heating system to power the boilers. The next day, the cruiser was already towing the ship.

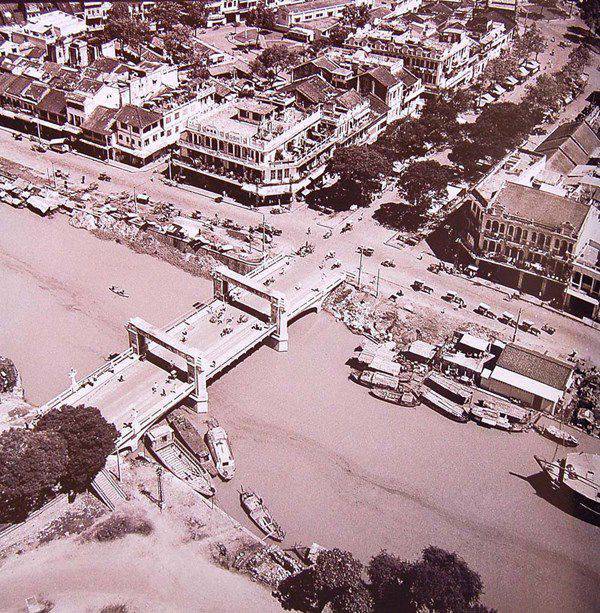

After four days of sailing, the Aramis, with the help of tugboats, led the Selenga to the port of Saigon and set it to the pier in the military port. The crew, with motorboats, drove twenty miles up the Saigon River and placed them in some quarantine huts. There, the Russian sailors were with compatriots - the crew of the ship "Mayakovsky" of the Black Sea Shipping Company, led by captain G. Miroshnichenko. On the way from the USA to Vladivostok with a cargo of various equipment, this vessel was detained in the South China Sea by the French cruiser “La Mota Picke” and brought to Saigon. The reason for the detention was chosen the same.

Yaskevich and Miroshnichenko discussed the situation and wrote a protest to the governor of French Indochina, sending him through a French officer guarded by Russian sailors. Two days passed, but there was no answer.

Then the captains decided on extreme measures. After consulting with the crews, they declared a hunger strike. At first, the camp guards did not take this statement seriously. But when the sailors did not come for breakfast, lunch or dinner for two days, the guards began to worry. The camp commander, the French captain, begged to stop the hunger strike, but the Soviet crews stood their ground: the hunger strike would continue until the governor arrived.

And it worked. The next morning, though not the governor himself, arrived at the camp, but his representative with the rank of rear admiral. It turned out that the governor received our protest and had already reported it to Paris. From the visit of a high-ranking official, our sailors tried to extract the maximum benefit. He stated all the claims. The Soviet crews were not prisoners of war, but only temporarily interned citizens of a neutral country. The camp, where they were placed, did not meet the most basic requirements. In addition, the sailors' clothing did not match the local climate.

Admiral had to agree. He not only ordered the sailors to be transferred to a more suitable place, but also ordered the delivery of tropical outfit to both crews and the ration provided for French sailors.

The admiral kept his word. Just the next day, Soviet crews were transported by car to a former rubber plantation, a hundred miles south of Saigon. Although the conditions here could be considered satisfactory, the plantation was, nevertheless, fenced and guarded by French and Vietnamese soldiers under the supervision of French officers. Exit for the territory of the Soviet sailors was banned. Was issued to the crews and tropical clothing.

Despite the improvement in conditions, Yaskevich and Miroshnichenko were particularly worried about one question: until now, the fate of the Soviet courts was not known either in the Soviet representation or in their homeland, since they failed to convey the message during the seizure. It was decided to try to secretly contact the consuls of neutral countries in Saigon.

Writing a letter on behalf of the two captains to the Norwegian and Chinese consuls in Saigon, indicating the location of the Soviet crews, they appealed to these diplomats to inform the Soviet government about the detention of ships and the internment of crews. One Chinese from the attendants took the letter to its destination, of course, bypassing the camp administration. The Chinese man kept his word, and the letter, as it turned out later, reached its intended purpose.

About a week after that, the two consuls arrived in the camp, accompanied by French officers. What a surprise the French were when, in their presence, the consuls told us that the letter had been received and already transferred to Moscow. Thus, the main goal was achieved. The captains of the Soviet courts once again confirmed that the only request, claim and wish was for the crews to be released as soon as possible, returned to the ships and given, finally, the opportunity to return to their homeland.

It is clear that the foreign consul is not given the right to interfere in the actions of local authorities, but both of them firmly promised that they would be interested in the fate of the Soviet crews and ships and, as soon as something becomes known, they will surely inform the captains.

So it took more than four months before the long-awaited news came: an instruction was received from Paris concerning Soviet sailors. However, the French decided to leave the goods in Saigon until the end of the war. Protests Yaskevich and Miroshnichenko did not have success. However, it took at least one and a half months before the sailors returned to their vessels. "Selenga" was in the port already without cargo. The hull, superstructure, decks, mechanisms were covered with rust. Equipment, furniture, practical items are broken or stolen. To bring the ship to a seaworthy state, it took at least a month of intensive work of the entire crew. Part of the repair and restoration work on the orders of the governor was carried out by the forces and means of the Maritime Admiralty.

Finally, in May 1940, the Selenga was ready to sail. But it was not to return home in ballast, especially since a long transition was coming to Vladivostok. With the permission of the shipping company, the ship went to Hong Kong and from there with a load of nuts, butter and beans followed in his native Vladivostok, where 30 June arrived. So ended this flight, stretching almost half a year.

Sources:

Paperno A. Aleksey Pavlovich Yaskevich - the first captain of the first liberty, captain No. XXUMX of the war years // Lend-Lease. Pacific Ocean. M .: Terra, 1. C. 1998-243.

Yaskevich A. Interrupted voyage // Sea Fleet. 1985. No.8. C.74-76.

Shirokorad A. The fleet that destroyed Khrushchev. M .: VZOI, 2004. C. 59-60.

Shirokorad A. A short century of a brilliant empire. M .: Veche, 2012. C. 188.

Information