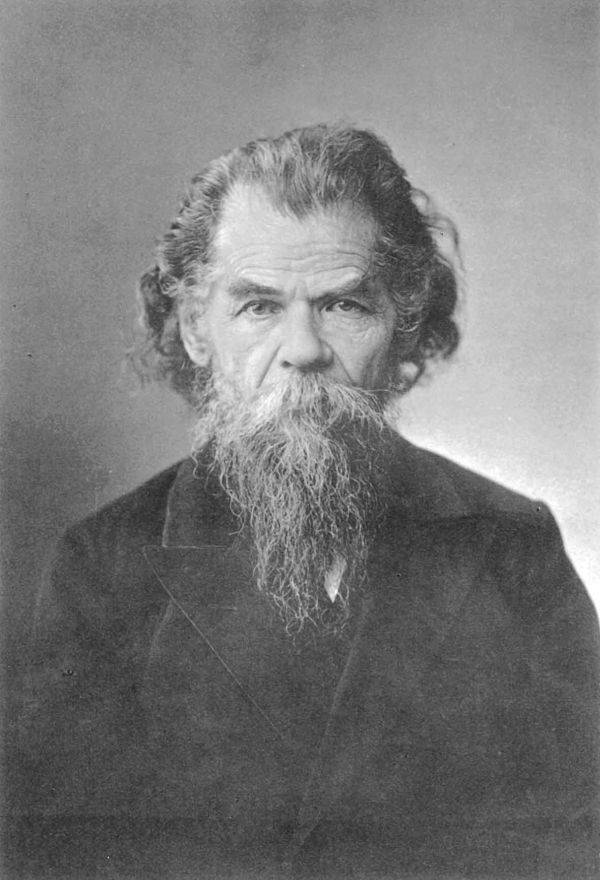

Siberian dad. Grigory N. Potanin

After the birth of Gregory, misfortunes fell upon the Potanins. The head of her for abuse of power came under investigation. To soften his fate, Nikolai Ilyich spent all the flocks and herds he inherited, but he did not succeed and finally collapsed. He was demoted to the rank and file and only under Alexander II received the title of cornet. In 1840, when Potanin Sr. was still in prison, his spouse died, and a cousin was involved in raising a child. After his release, the impoverished father took Gregory to his brother in the stanitsa Semiyarskaya. The uncle, who commanded the Cossack regiment, found his beloved nephew a good teacher, who taught the boy to read and write. However, two years later, my uncle died, and Gregory returned to his father in the village of Presnovskaya, where he lived until entering the cadet corps.

Considerable participation in the fate of the teenager was taken by the family of the commander of the Cossack brigade, Colonel Ellizen. He knew and respected Nicholas Ilyich well and took his son to his home, bringing up with his own children. Invited teachers taught the children of geography, arithmetic and Russian language. In general, Grigory Nikolayevich received a very good initial education, and the stories of his father and relatives, frequent trips through the villages and books from the extensive library of Ellizen contributed to the formation of his interest in nature and travel. At the end of the summer, 1846 Potanin Sr. took Gregory to the Omsk Military School (transformed into a cadet corps in 1848), training junior officers for Cossack and infantry units in Western Siberia.

In the cadet corps, Grigory Nikolayevich stayed for six years. Over the years, he has matured, noticeably physically strengthened and received an excellent initial training in the field of natural sciences. The young man showed particular interest in storiesforeign languages, geography and topography. By the way, among the best comrades of Potanin was a later Kazakh scientist Chokan Valikhanov, who spoke well and much about the life of his fellow tribesmen.

At 1852, seventeen-year-old Grigory Nikolayevich was released from the corps in the rank of cornet and sent to serve in the eighth Cossack regiment stationed in Semipalatinsk. In the spring of 1852, a detachment headed by university colleague Lermontov, Colonel Peremyshlsky, came out of Semipalatinsk to Kopal Fortress. It also included a hundred and eighth Cossack regiment with Grigory Nikolayevich. At the same time, military units from a number of other garrisons arrived at Kopal. The collected troops were divided into separate units, and Potanin was in the detachment of Colonel Abakumov. Soon the army moved to Zaili region. The young Cornet shared the burden of nomadic life on a par with everyone: before his eyes, Colonel Peremyshlsky raised a Russian flag in the Almaty area, and in the autumn 1853 took part in laying the foundation for Verny’s building - the first outpost in Semirechye, now Alma-Ata.

The initiative and courageous officer of the command began to trust responsible orders. At the end of 1853, Grigory Nikolayevich was sent to China for delivery of a shipment of silver to the Russian consulate. Potanin successfully accomplished this serious and dangerous task, having under his command a merchant guide and a couple of Cossacks. By that time, the successful advance of troops to Central Asia had stopped due to the start of the Crimean War. Leaving the garrison in Verniy, during the year military units returned to their places of deployment. In Semipalatinsk Potanin, having quarreled with the regimental commander, transferred to the ninth regiment stationed in the foothills of the Altai. There he led hundreds in the villages of Charyshskaya and Antonievskaya. Grigory Nikolaevich recalled: “Altai enraptured me, captivating me with pictures of my nature. I immediately loved him. ” At the same time, the young man showed a tendency to collect ethnographic material. He studied with interest the ways of local fishing and hunting, tillage techniques, agricultural work cycles, customs and customs of the local population. The information gathered served as the basis for creating his first serious work - the article “Half a Year in Altai”, which became a valuable source of the cultural and labor traditions of the Siberian peasantry of the nineteenth century.

The service on the Biyskaya line was interrupted at 1856 by transferring Potanin to the city of Omsk in order to analyze the archives of the Siberian Cossack army. Describing and systematizing archival documents, the young centurion made copies of the most interesting ones concerning the history of the colonization of Siberia. In the spring of 1856, on the way to Tien-Shan, the city of Omsk was visited by an unknown traveler Peter Semenov. Two days filled with troubles about the needs of the expedition were also marked by a meeting with an inquisitive Cossack officer who wrote out, despite his meager salary, the “Bulletin of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society”. Potanin told the Petersburg guest a lot of interesting things about Altai and Semirechye, and Petr Petrovich at the end of the conversation promised him assistance in entering the university. After the departure of Semenov, Potanin had a strong desire to retire. The military chieftain himself assisted him in this, in 1857 he instructed the doctor to find a "serious illness" with the centurion. As a result, a hernia was “discovered” in Grigory Nikolayevich, which allegedly prevented the young man from riding. Thus, in 1858 Potanin left military service.

Unfortunately, a similar turn of events posed another problem for Grigory Nikolayevich. For a trip to St. Petersburg and study at the university were needed and considerable funds. Potanin knew that the widow of his deceased uncle had married a certain baron, the owner of the Onufrievsky mine in Tomsk province. There, in the spring of 1858, Grigory Nikolayevich headed in the hope of getting an employee and honestly making his way. Relatives greeted the young man cordially, but they did not get a job, as things were going badly at the mine, and the baron was on the verge of bankruptcy. At the same time, the young man had the opportunity to see the organization of work on the extraction of gold, as well as the life of the mine workers, who were in terrible conditions. Impressions from the mines served as the basis for his article "On the working class in the near taiga", published in 1861. In the end, the ruined baron gave Potanin a letter of recommendation to his acquaintance, the exiled revolutionary Bakunin, who was in Tomsk. After the meeting, Bakunin escaped Potanin's permission to get to the northern capital along with a caravan transporting silver and gold mined in the district, and in the summer of 1859 Grigori Nikolayevich set off.

Soon after arriving in the city, a young Siberian got a job at St. Petersburg University as a volunteer. The source for existence was also found relatively quickly - they became literary earnings. For the first major work "Half a year in Altai", Potanin received an 180 rubles fee. For the former Cossack officer, it was a huge amount, exceeding the monetary maintenance of the centurion for the year. Subsequently, the level of his material condition depended on the attitude of editors of periodicals to his work. It was worth the change in the Russian Word edition, as Grigory Nikolayevich wrote: “I again fell into a state of fading. The boots were pierced and took a carse-like image ..., and the fear of sticking out of their reeds, as is the case with molting birds, has returned. ”

However, the financial situation bothered Potanin least. His body, hardened by nomadic life, easily endured a starvation diet and the St. Petersburg climate. All the forces of Siberian were directed to study, like a young student sponge absorbed new impressions, ideas, theories. In the summer of 1860, he traveled to the Ryazan province in the estate of the brother of his deceased mother to collect herbarium, and then to the city of Olonets and the island of Valaam with the same task. Summer vacation 1861 Potanin spent in Kaluga, making there a herbarium of local plants. In addition, with 1860, he participated in the activities of the Russian Geographical Society. In fairness it should be noted that the discussion of his first scientific report "On the culture of birch bark ware" ended in failure. The young man did not have enough knowledge, but Grigori Nikolayevich was not upset and, apart from visiting the university, he engaged in self-education. Gradually, the field of his scientific interests began to emerge - a comprehensive study of Siberia, its economic status, history, geography, ethnography, nature, and climate.

Three years (from 1859 to 1862) Potanin studied in St. Petersburg, but he did not succeed in obtaining a university education. In May, the Universities 1861 was approved by the new Rules, developed by the Minister of Education, Admiral Putiatin. According to the ninth paragraph, it was ordered to exempt from tuition fees only two students from each province included in the school district. After the release of the new rules, Potanin (like most Siberian students) was deprived of the opportunity to study at a university, because his literary earnings allowed him to make ends meet. It is not surprising that on the return of students from the holidays, protests began at the university, in which Grigory Nikolayevich took an active part.

In late September, Putyatin decided to close the university. This action gave rise to mass demonstrations of students and their clashes with the police. For more than a week, unrest continued, for participation in which more than three hundred people were arrested. One of the detainees was the "retired centurion of the Siberian Cossack Army Potanin". Among others, Grigory Nikolayevich was singled out in particular, as "seen in audacity." 18 October 1861 he was thrown into a separate cell of the Peter and Paul Fortress, where he stayed until December. The commission, which understood the degree of guilt of the arrested persons, did not find political intention in its actions. In a letter to a comrade from 20 December, 1861 Potanin wrote: “I leave St. Petersburg next autumn, or summer, of course, without a diploma.”

In April, 1862 Geographic Society elected a young man as its member-employee. In the summer of 1862, Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky helped Grigory Nikolayevich get a job as a translator and naturalist on the Struve expedition organized by the RGO to explore Lake Zaisan. At the same time, Potanin made an excursion to the South Urals, and in the fall went to the city of Omsk, as the starting point of the expedition. Here in March, 1863 assigned him to the General Administration of Western Siberia as a junior translator of the Tatar language. During the expedition to explore Lake Zaisan, Grigory Nikolayevich was responsible for collecting samples of insects and fish, as well as herbarium. The work stretched out until July 1864, Grigory Nikolayevich collected valuable material that became the basis for Struve's report on the expedition. After the end of the campaign in August, Potanin independently made a trip to the Old Believers who lived in the upper reaches of Bukhtarma. The completion of the work posed the problem of employment for the young researcher. In September, 1864 Grigory Nikolayevich was sent to Tomsk, where, by order of the local governor, he was appointed as a peasant affairs officer. In the city, in addition to his main work, he continued to actively engage in scientific research and ethnographic research, as well as searches in the local archive of sources on the history of Siberia. In addition, he taught natural history in female and male gymnasiums, and also published in a local newspaper.

Along with scientific problems, Potanin was interested in social activities, the beginning of which in university years was the creation of a circle of Siberian students discussing reforms in Siberia, contributing to its transformation into a cultural zone. In the newspaper, as well as in the youth circle formed by Grigory Nikolayevich, the problems of the transformations necessary in the region were considered, the ideas of Siberian patriotism and the opening of the university were promoted. Such activity alarmed the local administration and clouds began to thicken over Potanin. In May, 1865 he was arrested and brought to the investigation "in the case of the Siberian separatists." In total, fifty-nine people were detained in this case. Under a reinforced escort, Grigory Nikolayevich went to Omsk, where they were taken up by a specially constituted commission, which used the entire arsenal of influence adopted by the tsarist secret police - continuous interrogations were replaced by face-to-face rates, as well as offers to make a frank confession. At the end of November, the 1865 Investigation Commission ended its work, Potanin, who accepted the main fault, was accused of “malicious actions aimed at overthrowing the order of governance that exists in Siberia and its separation from the Empire.” The collected materials were sent to St. Petersburg, and the prisoner was drawn to months of dreary waiting.

Being uncertain about his further fate, Grigory Nikolaevich managed to maintain his composure and even obtained permission to continue systematization and analysis of the Omsk archive, and also wrote works on the history of Siberia of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Two and a half years Potanin waited for the verdict. The case was dealt with administratively in absentia, as judicial reform did not affect Siberia. The strengthening of the revolutionary movement in the country also greatly influenced the severity of punishment. Later, one of the prisoners stated: “The infernal shot of 4 on April 1866 changed the government’s views on our business.” Only in February, the 1868 Senate passed a sentence approved by the emperor and sent to Omsk for execution. According to him, Potanin was sentenced to five years of hard labor, and then sent to remote areas of the empire. The apparent softness of the verdict should not be deceiving - according to the criminal code of 1845 in the punishment system there were about 180 species and the second place (after the death penalty) was occupied by hard labor.

In May, before leaving for 1868 in Finland, where Grigory Nikolayevich was to serve his sentence, a civil execution was performed on him. Here is how the convict described him: “They put me on a chariot and hung a plate with an inscription on my chest. Moving to the scaffold was short ... I was erected on the scaffold, and the executioner tied his hands to the post. Then the official read out the confirmation. The time was early, and the sea of heads around the scaffold was not formed - the public stood in three rows. After keeping a few minutes at the post, I was untied and returned to the police department. ” In the evening of the same day, Potanin, shackled, was escorted by gendarmes to Sveaborg.

Potanin briefly reported about the next three years in penal servitude in one of the letters: “For the first year and a half he worked in squares, moved the taverns with a stone, smashed crushed stone with a hammer, sawed wood, chopped the ice, sang“ Dubinushka ”. Finally, the management identified me in dog dogs, and summer I spread horror in dog hearts. Then they raised it even higher - to the distributors, and then to the gardeners. We were fed oats, did not drink tea for three years, did not eat beef, and did not receive letters from anyone. ” With the help of sympathetic officers, Potanin managed to reduce the term of hard labor, and at the end of 1871 he was sent into exile in the city of Nikolsk, located in the Vologda province. There, under the patronage of the local police officer, Potanin got a job at the forester - writing petitions for the peasants. At the same time, a survey of applicants from various townships in the county allowed him to begin collecting ethnographic material. In addition, the researcher brought his extracts from the Tomsk archives to Nikolsk, based on which he compiled a resettlement map for Finnish and Turkic tribes in the Tomsk province. He sent this work to the board of the Geographical Society and received not only a benevolent review, but also a hundred rubles to continue the work, the necessary scientific literature and a number of measuring instruments.

In January, an important event happened in Potanin’s 1874 personal life - he was married to Alexandra Lavrskaya. Alexandra Viktorovna was kind of gifted - she knew French and English perfectly, drew well, was fond of collecting insects. One of his contemporaries wrote about her: “It was a shy and modest woman ... In society, she preferred to remain silent, but was distinguished by observation, the quality is very valuable for a traveler. Opinions and judgments of her were restrained, but accurate and witty. People she identified immediately. Her insight and knowledge of life complemented the lack of practicality of Grigory Nikolayevich, who was immersed in science, who knew reality very poorly. ” Subsequently, Alexandra Viktorovna, fragile and painful in appearance, became a constant companion and faithful assistant to Potanin in his expeditions.

Shortly after the marriage of 1874 in February, Grigory Nikolayevich sent a petition to the gendarme corps asking for pardon. He was supported by the vice-president of the RGO Peter Semenov, who assured that Potanin was “extremely“ talented scientist and honest worker ”. To the great joy of Grigory Nikolayevich in the summer of 1874 a letter came about his complete forgiveness, allowing the researcher to settle anywhere, including the capital. After visiting Nizhny Novgorod, where the relatives of Alexandra Viktorovna lived, the Potanins in late August 1874 arrived in St. Petersburg and rented a room on Vasilyevsky Island.

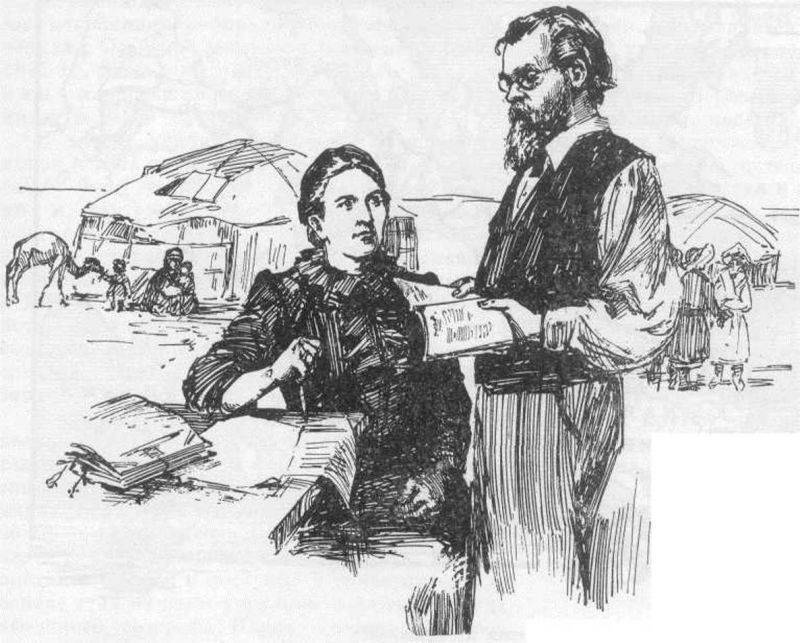

Ethnographer Grigory Potanin and journalist Alexander Adrianov amid the hut. The beginning of the twentieth century

Soon, Semenov-Tyan-Shansky suggested to Grigory Nikolayevich to take part in an expedition to northern China, and also, “in order to give money,” handed over the work that he began to do himself — to add to the third volume of Karl Ritter’s “Asia” dedicated to the Altai-Sayan Mountains the system. Instead of the 25 sheets of the 1875 Spring supplement, Potanin actually wrote a new volume in the 750 pages with data on ethnography and history. At the same time, Grigory Nikolaevich was actively preparing for the upcoming campaign. Under the guidance of the famous geologist Inostrantsev, he studied a microscopic analysis of rocks, and in the summer 1875 made an ethnographic tour of the Crimea, Kerch, Novocherkassk and Rostov-on-Don.

At the beginning of May, 1876 preparation for the journey was completed, and the Potanins went to Omsk. At the end of July, a small expeditionary detachment, which included, in addition to the spouses, a candidate of Oriental languages, a topographer, two Cossacks, a hunter and a student who worked as an ornithologist and taxidermist, left the Zaisan post on the way and after four day transitions found himself on the lands of China. The first Mongol expedition of Grigory Nikolayevich lasted until 1878. Having traveled east of Lake Zaisan, travelers crossed the Mongolian Altai and reached the city of Kobdo, where they stopped for the winter. During the stay, which lasted until spring 1877, the researchers processed and systematized the collected material, and Potanin carefully studied the life of the local population. At the end of March, the expedition left Kobdo and moved south along the northern spurs of the Mongolian Altai. Having crossed the Gobi, in the middle of May the travelers reached the Chinese city of Barkul in the foothills of the Tien Shan. Then, after visiting the city of Hami, the expedition crossed the Gobi for the second time, visited the Mongolian city of Ulyasutai, at the Lake Kosogol and ended the march in Ulangom.

Returning to the capital, Grigory Nikolayevich engaged in processing the collected materials, while preparing for a new campaign. The collections delivered to them made a real sensation in academic circles. The researcher wrote: “Scientists run after my collections, and the Academy of Sciences has already competed with the Entomological Society”. In addition to extensive geological, zoological and botanical collections, ethnographic materials and route surveys, the expedition brought information about the routes through Mongolia and about trade in the cities visited.

In March, 1879 Potanins went to Omsk to take part in the second Mongol-Tuva expeditions. The hike began from the village of Kosh-Agach in the Altai. Through the city of Ulang, past the Khirgis Nur lake, the travelers arrived in Kobdo, then crossed the Tannu-Ola ridge and drove up the Ulukem and Hakem rivers. In the late autumn, they went through Irkutsk through the Sayans and Tunku to winter. However, the continuation of the campaign was prevented by complications with China, and in December 1880 Potanins returned to the northern capital. All information obtained in two trips was revised by Grigory Nikolayevich and published in 1883 by the geographical society in the form of four volumes of "Outlines of North-Western Mongolia".

Already in early February, the 1881 researcher informed his comrades about his new journey to China. The interest in this project turned out to be so great that the emperor himself allowed to use the help of the warship sent to the Pacific Ocean, the steam ship frigate Minin. In August, 1883 expedition members went on it in long voyage. In mid-January, they were already in Jakarta 1884, where the propeller had broken at the ship. Travelers transplanted to the corvette "Skobelev", which transported before this another well-known researcher Miklukhu-Maclay. In April, the ship landed travelers in the town of Chief, from where they arrived on the steamer in Tianjin. Through Beijing, the northern provinces of China and the Ordos plateau, by the end of 1884, the travelers reached Gansu. For a whole year, Potanin studied the eastern outskirts of Tibet, and then, through the Nanshan ridge and central Mongolia, returned to Russia. The expedition ended in October 1886 in the city of Kyakhta - its participants, who collected enormous in volume and unique in composition material, were left behind more than 5700 kilometers of the road.

In fact, the world tour brought Grigori Nikolaevich all-Russian glory. The Russian Geographical Society awarded him with the highest award - the gold medal of Constantinople. One of his contemporaries wrote about him: “Potanin, who has already exceeded fifty years, impressed with his healthy and youthful appearance. A well-preserved man, he was slightly below average height, stocky, well-knit and well-built, with a hint of Kyrgyz origin. He had seen and experienced a lot, he was an interesting interlocutor, well-read and versatile, possessing considerable erudition ... ".

Until July, 1887 Potanins lived in St. Petersburg, and in October arrived in Irkutsk, where Grigory Nikolayevich back in March of this year was chosen as the ruler of the affairs of the East-Siberian department of the Russian Geographical Society. Being in this position before 1890, the famous travel scientist showed himself to be an outstanding science organizer. Receiving a poor subsidy of two thousand rubles each year for the maintenance of the department, he managed to significantly increase the budget thanks to donations from local entrepreneurs. The proceeds were directed to the expansion of activities, as well as the creation of new sections, in particular statistics, ethnography, physical geography. Public reports on natural science issues, which Potanin himself has repeatedly spoken about, have also become commonplace. At the same time, the couple lived in Irkutsk very modestly, renting one room in the outhouse.

In the summer of 1890, Grigoriy Nikolayevich made the decision to leave Irkutsk, because he was too busy with his affairs and could not finish the report on his expedition to China. Potanins arrived in St. Petersburg in October and stayed there for two years. The scientific works of the researcher made an indelible impression on the general public. In the books of the scientist there were no descriptions of trips and battles with wild tribes, but only a living perception of an unfamiliar, but interesting, life of peoples, imbued with respect and love for them. Like no other, Grigory Nikolayevich was able to show a high culture and rich inner world of the inhabitants of Central Asia. It should be noted that in contrast to Przhevalsky and Pevtsov, who traveled with a military convoy, the Potanins had not only protection, but even weapons. As a result, local residents felt more confidence in them than in other travelers. Even the Tanguts and Shiraegurs, the tribes who were considered inveterate brigands, were friendly to Grigori Nikolaevich, helping the expedition in everything. Potanins spent much of their time in villages and camps, Buddhist monasteries and Chinese cities, and therefore they studied the life and customs of these peoples unlike other travelers. A spouse of the researcher has collected unique information about family life and intimate atmosphere, inaccessible to other men.

The wealth of results collected by Grigory Nikolayevich prompted the RGO to 1892 to equip the fourth expedition under his command to continue research on the eastern edge of Tibet. After agreeing on the financing and organization of the upcoming campaign, the couple went to Kyakhta in the autumn, where the other participants gathered. Already in Beijing, where travelers arrived in November 1892, there was a problem with Alexandra Viktorovna's health - her body was greatly weakened by previous travels. The doctor who examined her at the Russian embassy informed about the importance of complete peace, but the brave woman flatly refused the offer to leave the expedition and responded to all persuasion that she could not let go of Grigory Nikolayevich alone.

16 December caravan made a tour through the city of Xian to the foothills of Tibet. In April, the travelers were already in Dajiang. Here Alexandra Viktorovna became completely bad. The expedition went back to Beijing, but on the way Potanin’s wife was struck by a stroke attack. 19 September 1893 Alexandra Viktorovna passed away. The shock of Grigory Nikolayevich was so strong that he refused to further participate in the campaign, allowing the satellites to make their own decision to continue the research work. He left for Russia by sea, and through Odessa and Samara he reached St. Petersburg.

After the death of his wife, Potanin no longer embarked on major expedition projects. In April, 1895 he visited Smolensk and Omsk, and then went to the Kokchetav district in the homeland of the deceased friend Chokhan Valikhanov. In addition to the memorial component, the trip was aimed at collecting ethnographic and folklore material in Kazakh camps and auls. In 1897, the traveler traveled to Paris and Moscow, and in the summer 1899 traveled to Siberia, where he made an expedition to explore the mountains of the Great Khingan. The main goal was to study legends, beliefs, legends, proverbs and tales of the Mongolian tribes living there. A brief essay on this trip came out in 1901, at the same time saw the light of the report on the last trip to China.

At the same time Potanin made the final decision to return to permanent residence in Siberia. In July, 1900 he arrived in Irkutsk, where he was greeted very cordially and re-elected governor of the affairs of the East-Siberian department of the RGO. However, the tireless researcher did not stay at this place - in May 1902 he moved to Tomsk, where he lived the remaining years. In the city, Grigory Nikolayevich was actively involved in scientific, cultural and educational activities - led the Board of the Society for the Care of Primary Education, was the keeper of the Tomsk Museum of Applied Knowledge, organized the Tomsk Society for the Study of Siberia, the Siberian student circle, the literary and artistic circle, the literary and dramatic society. One of the townspeople recalled: “All novice poets and writers, teachers and teachers, students and girl students, as they were stretching toward the sun, felt in him not a general from literature, not a strict mentor, but an older, simple and kind fellow. dared to joke and argue, and who himself indulged everyone with his jokes, stories and tales about the East ”.

It is worth noting that at the same time the financial situation of the famous traveler was very deplorable. In a letter to his friend, he reported on this occasion: "I live on my retirement, I can not earn a raise to it and I do not know how." Living on twenty-five rubles a month was truly difficult. And then Potanin's friends inclined him to write memories, so that in addition to a small fee for random articles, the famous traveler could have at least some kind of income. However, for 1913, Grigoriy Nikolayevich had a weak vision, because of the cataract, he could no longer write on his own, and was forced to dictate his memoirs.

In 1911, Potanin, for the second time, married the Barnaul poetess Maria Vasilyeva. With her, the researcher was in long correspondence, and also participated in her literary activities. Grigory Nikolayevich hoped that Vasilyeva could replace his late wife, but he was cruelly mistaken. In 1917 she left the already seriously ill traveler and went home to Barnaul.

The February revolution caught Potanin in the midst of the work on the memories. Despite its factual and formal detachment from the real political processes in the eyes of the participants and leaders of the anti-Bolshevik movement in the first half of 1918, Potanin remained the most authoritative leader in Siberia. At the end of March, 1918, on behalf of his comrades, he addressed the appeal “To the population of Siberia”, which was distributed in the form of leaflets and printed in newspapers.

Shortly before his death, Grigory Nikolayevich said to the landlady: “So I am dying. My life is over, but sorry. I want to live, I want to know what will happen next with sweet Russia. ” Potanin died on 30 on June 1920 at eight in the morning and was buried in the “professorial” part of the cemetery of the St. John the Baptist Convent. After World War II and the monastery, and the cemetery went for demolition. With great difficulty, local enthusiasts in the fall of 1956 managed to rebuild the remains of a great traveler to the University Grove of Tomsk University. In 1958, a bust monument was unveiled at the tomb of Potanin.

According to the materials of the book V.A. Obrucheva “Grigory N. Potanin. Life and Activities "and a biographical sketch of M.V. Shilovsky "G. N. Potanin "

Information