Closed triangle

The Western Balkan region is an inter-band living of divided peoples, a neighborhood of different ethno-religious groups and a search for their own identity through bloody clashes with their neighbors. Being in the center of this hopelessly tangled labyrinth, I tried to find out what was the path of the Serbian people to build their own identity and in what form this identity was formed by now.

Where did the Serbian land come from?

Considering the archaeological artifacts in Serbian museums, I discovered the presence of Celts, Romans, Byzantines, Huns, Goths, Avars in those territories that are now inhabited by Serbs. Interestingly, on the site of modern Belgrade BC there was the Roman city of Singidunum, one of whose viaducts became the foundation of the main walking street of the Serbian capital. And in the territory of the third largest Serbian city of Niš in the southern part of the country, the Byzantine emperor Constantine I the Great was born.

And where is the place for the Serbs themselves in this kaleidoscope of successive great nations? Although Serbo-Croats appear in the Western Balkans already in the VII century AD, Serbia as a separate state is made out only at the end of the XII century. At the same time, it is important that by this period its neighbors - Hungary, Croatia and Bosnia - had already been differentiated by state entities for several centuries. It seems that Serbia looked like a younger brother in this nascent Balkan "family".

Moreover, the country remained independent for less than two centuries. Already in 1389, on the day of St. Vitus (Vidovdan), the Serbs were defeated by Turkey in the Kosovo field. Despite the fact that this event opens the period of the enslavement of the Serbs, it underlies the mythologicalhistorical ideas of the Serbian people about themselves. It turns out that the separation of Serbs from the surrounding historical and geographical context occurs according to the principle of "losers" and "Orthodox".

Belgrade ... how much of this sound ...

Further ups and downs of the Serbian people can be traced to the history of Belgrade, in which they are reflected, as in a mirror. The real revelation for me was such a nuance: Belgrade throughout its existence has been controlled by the Serbs in the aggregate for no more than three hundred years (intermittently), while the Turks and Hungarians dominated it, respectively, five hundred. At the same time, the Serbs had an extremely low status: they were forbidden to enter the Turkish fortress around the Kalemegdan park, as well as in the central part of Belgrade. Could the Serbs find a worthy place in such conditions, including psychologically? Hardly.

This search was complicated by the constant proximity to the border zone. In fact, the left bank of the Sava River, where modern New Belgrade and the Zemun district are located, belonged to Hungary until the end of the First World War. They became part of Belgrade only in the middle of the 1930-s.

And how did national consolidation occur in such conditions? Given that the Serbs themselves were not masters in their own homes for centuries and did not have the slightest relation, for example, to the construction of their capital? And here the images of martyrdom and Orthodoxy come to life again: at the end of the 19th century, the construction of the grandest Orthodox church began in the place where the Turkish authorities ordered to burn the relics of St. Sava.

Surrounded by enemies

The evolution of Serbian identity towards martyrdom also occurred under the influence of a direct existential threat, coming from both immediate neighbors and external conquerors. In their environment were cultivated ideas for the destruction of the Serbs or keeping them in slave condition.

In the novel of the Serbian Nobel laureate in literature, Ivo Andric, “The Bridge on the Drina”, the monstrous executions to which the Serbs were subjected to disobeying the Turkish authorities were described. People were put alive on a stake, put their severed heads on public display, fed their corpses to dogs.

In general, sophisticated fear actions were a common means of suppressing Serb national sentiments and bringing them to a state of sacrifice. In the year 1809, after one of the Serbian uprisings near the city of Nis, the Turks instilled the skulls of the fallen Serbs into the wall and put it on the main road of the city.

Chele-Kula in the city of Niš is a wall of Serb heads killed by the Turks during the first Serbian uprising at the beginning of the 19th century.

Photo: miki mikelis / Flickr

In a later period, at the end of the XIX century, already in neighboring Croatia began to see the mood that became the forerunner of fascism. The theory of “Croatian rights” by Ante Starcevic, in particular, substantiated the claims of the Croats on their own state, which would cover the territories of Serbia and Bosnia, but would not include the Serbs themselves. This theory formed the basis of the policy of the pro-fascist Independent State of Croatia 1941 – 1945, which practiced physical extermination, conversion to Catholicism and eviction of the Serbs - according to 200, thousands of people, respectively. This regime was also controlled by the concentration camp Jasenovac, which was later called "the largest Serbian city under the ground."

Big Brother

Were there any examples in Serbian history that could have contributed to the tendency opposite to martyrdom? Yes. So, Serbia became the first Western Balkan state to emerge from the power of the great empires. It turns out that by the end of the First World War - by the time the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes were formed - it was she who was able to unite around herself territories that had for centuries felt a shortage of their own statehood. This position of Serbia as an “elder brother” was also formalized: the Serbian king stood at the head of the new state.

However, about one and a half centuries of "seniority" did not change the old vector of development of Serbian identity. The unified state did not propose new ideas that would be comparable in attractiveness with sacrifice. In this regard, it seems logical that it was the Serbian President S. Milosevic’s underlining of the idea of Serbs being disadvantaged within the federation (“Yugoslavia is a mistake, since the Serbian people sacrificed too much in favor of unity, and instead of gratefulness from other republics, it receives only more hostility”) became the first chord in the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Prince and Dirt

Are these ideas of sacrifice so deeply rooted and reproduced not only for political, but also for psychological reasons? From this assumption the blood runs cold, but it seems that the Serbs themselves are taking away the place of the victim. Where does this conclusion come from? The leitmotif of all current historical expositions are photographs and information about those shot, hanged, tortured.

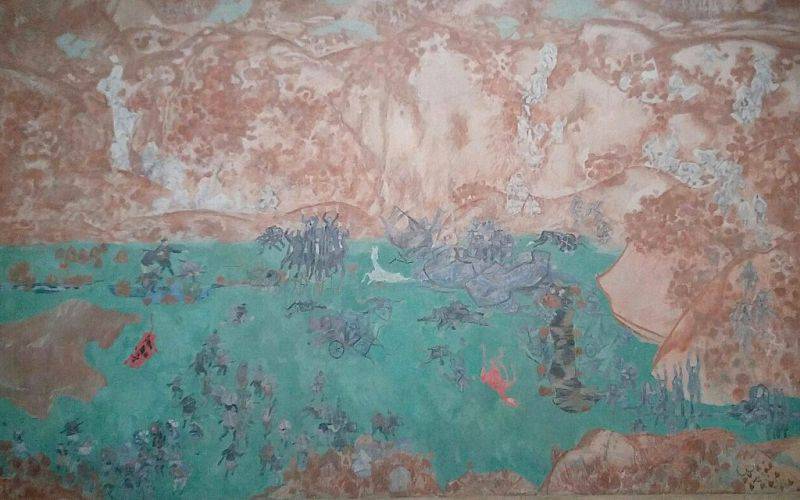

The most characteristic manifestation of this plot is a grand fresco in the Museum of the History of Yugoslavia, which illustrates all Serbian suffering, starting from the Middle Ages and ending with the surrender to the German invaders. Moreover, in this museum, five of the six rooms are dedicated to scenes of suffering and executions during the Second World War, but only one, half-empty - victory. Even the famous Yugoslav partisan movement is not presented with the help of images of strong-willed and physically strong people; they are more like shapeless ghosts, knowingly awaiting death rather than feat.

Fragment of fresco in the Museum of the History of Yugoslavia.

Photography: Natalia Konovalova / Politica Externa

The second pole of the same phenomenon is the exaltation of the liberator leaders. These include Prince Milos Obrenovic, the leader of the Serbian uprisings; and Prince Mikhail III Obrenovicz, who received the keys to Belgrade from the hands of the governor of the Sultan; and, of course, Josip Broz Tito. As for the latter, it is impossible not to draw attention to the huge amount of his rewards, to ascribing to him all the possible talents and merit. And, finally, on the myth that Yugoslavia was based on it alone, whose freedom he single-handedly won and whose wealth he built with his own hands.

This phenomenon could easily be called primitive propaganda, if not for one circumstance. The exaggerated endowment of the figure of the leader-rescuer with all conceivable and inconceivable virtues, adjacent to the feeling of sacrifice among the people, reflects the “victim-aggressor-rescuer” stuck in the corridor. This indicates the presence of severe psychological trauma nationwide.

In the same paradigm, there are also the notorious nationalist leaders (“aggressors”) Drazha Mihajlovic, the leader of the Serbian Chetniks during the Second World War, and Ratko Mladic, the general of the Bosnian Serb armed forces in 1990's. Souvenir paraphernalia with their portraits in abundance is presented on the main walking street of Belgrade; books about them are found even in the tiniest kiosks, etc. In other words, the atmosphere is saturated with charged images that appear to be "avengers" for oppressing the Serbs and justify aggression with previous sufferings.

Lamb of the slaughter

Most paradoxically, the other key element of Serbian identity - Orthodoxy - is only an additional brick, on which the national sacrificial altar stands. Thus, in the Orthodox Church in Visegrad (Republika Srpska), next to the icons, there are stands that label the Independent State of Croatia for the suffering it has subjected the Serbs. In addition, the cemetery is located next to another Vyshegrad Orthodox Church, where the Serbian military who fell in 1992 – 1995 are buried. Completes the picture observed in Vidovdan, 28 of June, the exaltation of the Serbs about the murder of Herz-duke Franz Ferdinand on this sign day.

The place where all these strongest images - the cult of power, the depressed state of the people and the Orthodox faith - connected, for me was the residence of Tito (now Tito's mausoleum at the Museum of Yugoslavia). Amazingly, from the balcony of the residence of the socialist leader a perfect perspective opens up to the Cathedral of Saint Sava. Moreover, these two points are visually on the same level, located on the two highest hills of old Belgrade. As if we are talking about the equivalence of these two centers, which, like the whales, support themselves the dominant national complex.

The combination of such phenomena as immersion into the image of the victim and self-identification on the basis of religious principles determined the nature of the 1990's Yugoslav ethnic conflicts. Thus, the Serbian entities formed after the collapse of the single federation justified aggression against other ethno-religious groups by the suffering that had been caused to the Serbian people in the past.

The saddest example is the reissue in 1992 of a previously banned book, The Bloody Hands of Islam. It listed the crimes of the Croats and Muslims against the Serbs, which were committed in the region of Srebrenica during the Second World War. This increased the Serb fear of the Muslim population and prepared the ground for the tragedy in Srebrenica 11 on June 1995, when more than 8 of thousands of male Bosnian Muslims underwent ethnic cleansing.

"Three-headed eagle" and decapitated buildings

The peak of the Serbian traumatic triangle was the appearance on the national arena of a “three-headed eagle” - Slobodan Milosevic. His figure became a kind of container, which contained all three images: the rescuer, the aggressor, the victim. It is not surprising that such descriptions as the national hero, the Balkan butcher and the Serbian martyr are simultaneously used to describe it.

So, at the end of 1980, he provided political support to Kosovo Serbs who accused Albanians of genocide, as a result of which he earned the image of a defender. However, due to the “massacre” of the Kosovo Albanian gangs at the end of 1990, as well as the encouragement of Serb units in conflicts with the Croats and Bosniaks, Milosevic gained fame as a bloody dictator and aggressor.

The circumstances of his extradition to the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and his death in custody turned Milosevic’s victim. For example, Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic, to the last, assured that Milosevic would first appear before a court in the country and only then before the Hague Tribunal. However, in exchange for donor assistance from international lenders, the former president was secretly transferred to the ICTY. Subsequently, Milosevic died in prison allegedly from a heart attack — a substance was found in his blood that contributes to an increase in pressure.

But despite the fact (and, perhaps, on the contrary, precisely for this reason) that S. Milosevic psychologically represents the tip of the Serbian national iceberg, he is among those “whom it is impossible to talk about.” I could neither see nor hear about him.

But more convincingly than any words - the attitude of the Serbs to a kind of symbol of the Milosevic era, that is, the buildings of the General Staff and the Ministry of Defense, destroyed during the bombing of Belgrade by NATO forces. It is significant that in the middle of the 2000's they were officially recognized as historical monuments. And now these torn wounds on the body of the capital are “roads as memory” to many citizens, which is why the measures to restore them are postponed.

It turns out that the repression of Slobodan Milosevic’s image from the national context is compensated by the hypervalue attributed to crippled twin buildings - the symbol of sacrifice in stone and glass.

Like these buildings, which can neither find integrity nor cease to exist, the Serbian people are not able to achieve stability and certainty. As long as the psychological triangle, one of the vertices of which is sacrifice, remains closed, there can be no talk of a healthy national identity. This is a misfortune that entails several others at once - the susceptibility of any kind of manipulation, the ability to flare up from the slightest spark.

Perhaps the closure of another geometric shape - the boundary line - can reduce the severity of this problem. Indeed, only with a feeling of constancy of one’s own place and one’s own value is it possible to untie this age-old Gordian knot.

- Natalia Konovalova, editor of the Europe column for Politica Externa, student at the Faculty of World Economy and World Politics, HSE

- http://politicaexterna.ru/post/124575841581/balkans

- Raffaele Esposito / Flickr

Information