Soviet heroes freed the "eternal city". Roman underground

Creation of the resistance movement in Italy

One of the most numerous and active partisan movements against fascism unfolded during the Second World War in Italy. In fact, the anti-fascist resistance in Italy began as early as the 1920s, as soon as Benito Mussolini came to power and established the fascist dictatorship. The resistance was attended by communists, socialists, anarchists, and later - and representatives of leftist movements in fascism (there were those who were dissatisfied with Mussolini’s union with Hitler). However, before the start of the Second World War, the anti-fascist resistance in Italy was scattered and relatively successfully suppressed by the fascist militia and the army. The situation changed with the beginning of the war. The resistance movement was created as a result of combining the efforts of individual groups formed by representatives of the Italian political opposition, including the military.

It should be noted that the Italian partisan movement after the overthrow of Mussolini and the occupation of Italy by the Nazis, received great support from the Italian army. The Italian troops, who had sided with the anti-fascist government of Italy, were sent to the front against the Hitler army. Rome defended the divisions of the Italian army "Granatieri" and "Ariete", but later they were forced to withdraw. But it was from the warehouses of the Italian army that the partisan movement received most of its weapons. Representatives of the Communist Party, led by Luigi Longo, held talks with General Giacomo Carboni, who led the military intelligence of Italy and at the same time commanded the mechanized corps of the Italian army, who defended Rome from the advancing Nazi troops. General Carboni ordered Luigi Longo to hand over two trucks of weapons and ammunition intended for the deployment of a partisan movement against the Nazi occupiers. After the 9 of September of 1943, the Italian forces defending Rome ceased resistance and units of the Wehrmacht and the SS entered the Italian capital, the only hope remained for the partisan movement.

9 September 1943 was created the Committee of the National Liberation of Italy, which began to play the role of the formal leadership of the Italian anti-fascist partisan movement. The Committee of National Liberation includes representatives of the Communist, Liberal, Socialist, Christian Democratic, Labor Democratic Party and Party Action. The leadership of the committee maintained contact with the command of the armed forces of the countries of the anti-Hitler coalition. In Northern Italy, occupied by Hitler's troops, the Committee for the Liberation of Northern Italy was created, to which the partisan formations operating in the region were subordinate. The guerrilla movement consisted of three key armed forces. The first, the Garibaldi Brigades, was controlled by the Italian Communists, the second, the Justice and Freedom organization, was under the control of the Action Party, and the third, the Matteotti Brigades, was subordinate to the leadership of the Socialist Party. In addition, there were few guerrilla groups in Italy, staffed by monarchists, anarchists and anti-fascists without clearly expressed political sympathies.

25 November 1943, under the control of the communists, the formation of the Garibaldi brigades began. By April 1945, there were 575 Garibaldian brigades operating in Italy, each of which included approximately 40-50 guerrillas, united in 4-5 groups of two links of five people. The direct command of the brigades was carried out by the leaders of the Italian Communist Party, Luigi Longo and Pietro Secchia. The number of Garibaldi brigades was about half of the total number of Italian partisan movements. On the account of the Garibaldi brigades created by the communists, only for the period from the middle of 1944 to March of 1945 - no less than 6,5 of thousands of military operations and 5,5 of thousands of sabotage against the objects of occupation infrastructure. The total number of fighters and commanders of the Garibaldi brigades by the end of April 1945 was at least 51 thousand people, united in the 23 division of the partisans. Most of the divisions of the Garibaldi brigades were stationed in Piedmont, but also the partisans operated in Liguria, Veneto, Emilia and Lombardy.

Russian "Garibaldi"

Into the ranks of the Italian Resistance, many Soviet citizens joined the ranks of prisoner of war camps or in other ways that turned out to be in Italy. When the German prisoner of war camps were overcrowded, a large part of the captured soldiers and officers of the Allied forces and the Red Army were transferred to camps in Italy. The total number of prisoners of war in Italy reached 80 thousand people, of whom 20 thousand people were military personnel and civil prisoners of war from the Soviet Union. Soviet prisoners of war were stationed in the north of Italy - in the industrial region of Milan, Turin and Genoa. Many of them were used as labor during the construction of fortifications on the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian coasts. Those of the prisoners of war who were lucky enough to escape, joined the partisan detachments and underground organizations operating in cities and rural areas. Many Soviet soldiers, breaking through to the territory of active activity of the Italian partisans, joined the Garibaldi brigades. Thus, the Azerbaijani Ali Baba oglu Babayev (born 1910), who was in a prison camp in Udine, with the help of the Italian Communists, fled from captivity and joined the Garibaldi brigades. As an officer of the Red Army, he was appointed to the post of the Chapaev battalion created as part of the brigades.

Vladimir Yakovlevich Pereladov (b. 1918) in the Red Army served as commander of an anti-tank battery, was captured. He tried to escape three times, but failed. Finally, already in Italy, good luck smiled at a Soviet officer. Pereladov fled with the help of the Italian Communists and was transferred to the province of Modena, where he joined the local partisans. As part of the Garibaldi brigades, Pereladov was appointed commander of the Russian shock battalion. Three hundred thousand lire were promised by the occupation authorities of Italy for capturing "Captain Rousseau", as the locals called Vladimir Yakovlevich. Pereladov’s squad managed to inflict tremendous damage on the Hitlerites — destroy 350 vehicles with soldiers and cargo, blow up the 121 bridge, capture at least 4 500 captured soldiers and officers of the Hitler army and Italian fascist formations. It was the Russian shock battalion that was one of the first to break into the city of Montefiorino, where the famous partisan republic was created. The national hero of Italy was Fedor Andrianovich Poletayev (1909-1945) - a private soldier, an artilleryman. Like his other comrades - the Soviet soldiers who found themselves on Italian soil, Poletayev was captured. Only in the summer of 1944, with the help of the Italian Communists, did he manage to escape from the camp located in the vicinity of Genoa. After fleeing from captivity, Poletayev joined the Nino Franchi battalion, which was part of the Orest Brigade. Colleagues in the partisan detachment called Fedor "Poet". 2 February 1945, during the battle in the valley of the Lightning Valle - Scrivia, Poletaev rose to the attack and forced most of the Nazis to drop their weapons. But one of the German soldiers shot at a brave partisan. Wounded in the throat Poletayev died. After the war he was buried in Genoa, and only in 1962 was the feat of Fyodor Andrianovich appreciated even at home — Poletayev was posthumously awarded the high title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Vladimir Yakovlevich Pereladov (b. 1918) in the Red Army served as commander of an anti-tank battery, was captured. He tried to escape three times, but failed. Finally, already in Italy, good luck smiled at a Soviet officer. Pereladov fled with the help of the Italian Communists and was transferred to the province of Modena, where he joined the local partisans. As part of the Garibaldi brigades, Pereladov was appointed commander of the Russian shock battalion. Three hundred thousand lire were promised by the occupation authorities of Italy for capturing "Captain Rousseau", as the locals called Vladimir Yakovlevich. Pereladov’s squad managed to inflict tremendous damage on the Hitlerites — destroy 350 vehicles with soldiers and cargo, blow up the 121 bridge, capture at least 4 500 captured soldiers and officers of the Hitler army and Italian fascist formations. It was the Russian shock battalion that was one of the first to break into the city of Montefiorino, where the famous partisan republic was created. The national hero of Italy was Fedor Andrianovich Poletayev (1909-1945) - a private soldier, an artilleryman. Like his other comrades - the Soviet soldiers who found themselves on Italian soil, Poletayev was captured. Only in the summer of 1944, with the help of the Italian Communists, did he manage to escape from the camp located in the vicinity of Genoa. After fleeing from captivity, Poletayev joined the Nino Franchi battalion, which was part of the Orest Brigade. Colleagues in the partisan detachment called Fedor "Poet". 2 February 1945, during the battle in the valley of the Lightning Valle - Scrivia, Poletaev rose to the attack and forced most of the Nazis to drop their weapons. But one of the German soldiers shot at a brave partisan. Wounded in the throat Poletayev died. After the war he was buried in Genoa, and only in 1962 was the feat of Fyodor Andrianovich appreciated even at home — Poletayev was posthumously awarded the high title of Hero of the Soviet Union. The number of Soviet partisans who fought on the territory of Italy is estimated by many thousands of modern historians. Only in Tuscany, 1600 Soviet citizens fought against the Nazis and local fascists, about 800 Soviet soldiers and partisan officers in the province of Emilia-Romagna, 700 people - in Piedmont, 400 people - in Liguria, 400 people - in Lombardy, 700 people - in Vienna. It was the number of Soviet partisans that prompted the leadership of the Italian Resistance to start forming "Russian" companies and battalions as part of the Garibaldi brigades, although, of course, among the Soviet partisans there were not only Russians, but also people of various nationalities of the Soviet Union. In the province of Novara, Fora Mosulishvili (1916-1944) accomplished his feat - a Soviet soldier, Georgian by nationality. Like many of his peers, with the beginning of the war, he was drafted into the army, received a foreman rank, was captured in the Baltic States. In Italy, he was lucky to escape from a prisoner of war camp. 3 December 1944, the detachment in which Mosulishvili was, was surrounded. The Nazis blocked the partisans in the dairy and repeatedly offered anti-fascists to surrender. In the end, the Germans, seeing that the resistance of the partisans did not cease, promised to save the life of the partisans if the platoon commander came first to them. However, the platoon commander did not dare to leave first, and then at the entrance to the cheese factory with the words "I am the commander!" Faure Mosulishvili appeared. He cried out “Long live the Soviet Union! Long live Free Italy! ”And shot himself in the head (G. Bautdinov“ We beat the fascists in Italy ”// http://www.konkurs.senat.org/).

It is noteworthy that among the partisans who came out in arms against the fascist dictatorship of Mussolini, and then against the Nazi troops who occupied Italy, there were also Russians who lived on Italian soil before the war. First of all, we are talking about white immigrants who, despite completely different political positions, found the courage to take the side of the communist Soviet Union against fascism.

Comrade Chervonny

When the Civil War in Russia began, the young Alexey Nikolayevich Fleisher (1902-1968) was a cadet - as befits a nobleman, a hereditary military man whose father served in the Russian army as a lieutenant colonel. Fleischer, Danes by birth, settled in the Russian Empire and got the nobility, after which many of them served the Russian Empire for two centuries in the military field. The young cadet Alexey Fleisher, along with his other classmates, was evacuated from the Crimea by the Wrangel. So he ended up in Europe - a seventeen-year-old youth, who yesterday was going to devote himself to military service to the glory of the Russian state. Like many other émigrés, Alexey Fleischer had to try himself in different professions abroad. Originally settled in Bulgaria, he got a job as a moulder at a brick factory, visited a miner, then moved to Luxembourg, where he worked at a leather factory. The son of a lieutenant colonel, who also had to wear officer shoulder straps, became an ordinary European proletarian. After moving from Luxembourg to France, Fleischer got a job as an excavator driver, then as an engineer of the cableway, was a driver for an Italian diplomat in Nice. Before the war, Alexey Fleisher resided in Belgrade, where he worked as a driver for the Greek diplomatic mission. In 1941, when Italian troops invaded Yugoslavia, Alexey Fleisher as a person of Russian origin was detained and sent to the beginning of 1942 in exile in Italy. There, under the supervision of the police, he was settled in one of the small villages, but soon managed to obtain permission to reside in Rome - even if under the supervision of the Italian special services. In October, 1942, Mr. Alexey Fleisher, got a job as a head waiter at the Embassy of Siam (Thailand). Thailand acted in the Second World War on the side of Japan, therefore it had a diplomatic mission in Italy, and the staff of the Siamese embassy did not arouse any special suspicions among the special services.

After the Anglo-American troops landed on the Italian coast, the embassy of Siam was evacuated to the north of Italy - into the zone of Nazi occupation. Alexey Fleisher remained to guard the empty embassy building in Rome. He turned it into the headquarters of the Italian anti-fascists, which were visited by many prominent members of the local underground. Through the Italian underground, Fleisher contacted Soviet prisoners of war who were in Italy. The backbone of the partisan movement was made up of the fugitives from the camps for prisoners of war, who acted with the active support of immigrants from Russia who lived in Rome and other Italian cities. Alexey Fleisher, a nobleman and white emigrant, received from the Soviet partisans the military nickname “Chervonny”. Lieutenant Alexey Kolyaskin, who took part in the Italian partisan movement, recalled that Fleisher, “an honest and brave man, helped his compatriots to run free and supplied them with everything they needed, including weapons” (quoted in: Prokhorov Y.I. Cossacks for Russia // Siberian Cossack Journal (Novosibirsk). - 1996. - № 3). Other Russian emigrants, who made up the whole underground group, provided direct assistance to Fleischer. An important role in the Russian underground was played by Prince Sergei Obolensky, who acted under the cover of the “Committee of patronage of Russian prisoners of war”. Prince Alexander Sumbatov and arranged for Alexei Fleischer as a headwaiter at the Thai embassy. In addition to the princes Obolensky and Sumbatov, the Russian emigre underground organization included Ilya Tolstoy, artist Alexei Isupov, mason Kuzma Zaitsev, Vera Dolgin, priests Dorofey Beschastny and Ilya Markov.

In October 1943, members of the Roman underground learned that in the suburbs of Rome, in the location of Hitler's troops, there was a significant number of Soviet prisoners of war. It was decided to deploy active work to help fugitive prisoners of war, which consisted in harboring the fugitives and transferring them to active partisan detachments, as well as food, clothing and weapons support for escaped Soviet prisoners of war. In July, the 1943 of the Germans delivered Soviet prisoners of war 120 to the outskirts of Rome, where they were first used in the construction of facilities, and then distributed between industrial enterprises and construction sites in nearby cities. Seventy prisoners of war worked on dismantling the aircraft factory in Monterotondo, fifty people worked at the car repair plant in Bracciano. Then, in October 1943, the command of the Italian partisan forces operating in the Lazio region, it was decided to organize the escape of Soviet prisoners of war held in the vicinity of Rome. The direct organization of the escape was entrusted to the Roman group of Russian émigrés under the direction of Alexei Fleischer. October 24 1943 Mr. Aleksey Fleisher, accompanied by two anti-fascists - the Italians went to Monterotondo, from where 14 prisoners of war escaped the same day. Among the first to flee from the camp was Lieutenant Alexei Kolyaskin, who later joined the partisans and took the most active part in the armed anti-fascist struggle in Italy. In total, the Fleisher group rescued 186 Soviet soldiers and officers who were captured in Italy. Many of them were transferred to partisan detachments.

Guerrilla groups in the outskirts of Rome

In the area of Genzano and Palestrina, a Russian partisan detachment was formed, staffed by escaped prisoners of war. He was commanded by Lieutenant Alexei Kolyaskin. In the area of Monterotondo there were two Russian partisan detachments. The command of both teams carried out Anatoly M. Tarasenko - an amazing man, Siberian. Before the war, Tarasenko lived in the Irkutsk region, in the Tanguysky district, where he was engaged in a completely peaceful affair - trade. It is unlikely that the Irkutsk salesman Anatoly could even in a dream imagine his future as a commander of a partisan detachment in a distant Italian land. In the summer of 1941, the brother of Anatoly Vladimir Tarasenko died in battles near Leningrad. Anatoly went to the front, served in artillery, was wounded. In June, 1942, the corporal Tarasenko, received a concussion, was captured. At first he was in a prisoner of war camp in Estonia, and in September 1943 was transferred to Italy along with other comrades in misfortune. There he fled from the camp, joining the partisans. Another Russian partisan detachment was formed in the region of Ottavia and Monte Mario. In Rome, a separate underground "Youth squad" operated. It was headed by Peter Stepanovich Konopelko.

Like Tarasenko, Peter Stepanovich Konopelko was a Siberian. He was in a prisoner of war camp guarded by Italian soldiers. Together with Soviet soldiers, French, Belgian and Czech soldiers were taken prisoner here. Together with his friend Anatoly Kurnosov, Konopelko tried to escape from the camp, but was caught. Kurnosova and Konopelko were placed in a Roman prison, and then transferred back to a prisoner of war camp. There, a D'Amico, a local resident of the underground antifascist group, contacted them. His wife was Russian by nationality, and D'Amico himself lived for some time in Leningrad. Soon Konopelko and Kurnosov fled from a prisoner of war camp. They escaped at Fleischer - on the territory of the former Thai embassy. Pyotr Konopelko was appointed commander of the Youth Squad. In Rome Konopelko moved, posing as a deaf-mute Italian Giovanni Beneditto. He supervised the transfer of escaped Soviet prisoners of war to mountainous areas — to partisan units operating there, or hiding fugitives in an abandoned Thai embassy. Soon, new underground members appeared in the embassy - sisters Tamara and Lyudmila Georgievskys, Pyotr Mezheritsky, Nikolai Khvatov. The Germans took the sisters of St. George from their native Gorlovka to work, but the girls managed to escape and join the partisan detachment as liaisons. Fleisher himself sometimes wore the uniform of a German officer and traveled around Rome for reconnaissance purposes. He didn’t arouse suspicion on Hitler’s patrols, since he spoke excellent German. Italian patriots — professor, MD, Oscaro di Fonzo, captain Adreano Tunney, doctor Loris Gasperi, cabinet maker Luigi de Dzorzi, and many other remarkable people of all ages and professions — stood shoulder to shoulder with the Soviet underground fighters operating in Rome. Luigi de Dzorzy was Fleischer's direct assistant and carried out the most important assignments of an underground organization.

Like Tarasenko, Peter Stepanovich Konopelko was a Siberian. He was in a prisoner of war camp guarded by Italian soldiers. Together with Soviet soldiers, French, Belgian and Czech soldiers were taken prisoner here. Together with his friend Anatoly Kurnosov, Konopelko tried to escape from the camp, but was caught. Kurnosova and Konopelko were placed in a Roman prison, and then transferred back to a prisoner of war camp. There, a D'Amico, a local resident of the underground antifascist group, contacted them. His wife was Russian by nationality, and D'Amico himself lived for some time in Leningrad. Soon Konopelko and Kurnosov fled from a prisoner of war camp. They escaped at Fleischer - on the territory of the former Thai embassy. Pyotr Konopelko was appointed commander of the Youth Squad. In Rome Konopelko moved, posing as a deaf-mute Italian Giovanni Beneditto. He supervised the transfer of escaped Soviet prisoners of war to mountainous areas — to partisan units operating there, or hiding fugitives in an abandoned Thai embassy. Soon, new underground members appeared in the embassy - sisters Tamara and Lyudmila Georgievskys, Pyotr Mezheritsky, Nikolai Khvatov. The Germans took the sisters of St. George from their native Gorlovka to work, but the girls managed to escape and join the partisan detachment as liaisons. Fleisher himself sometimes wore the uniform of a German officer and traveled around Rome for reconnaissance purposes. He didn’t arouse suspicion on Hitler’s patrols, since he spoke excellent German. Italian patriots — professor, MD, Oscaro di Fonzo, captain Adreano Tunney, doctor Loris Gasperi, cabinet maker Luigi de Dzorzi, and many other remarkable people of all ages and professions — stood shoulder to shoulder with the Soviet underground fighters operating in Rome. Luigi de Dzorzy was Fleischer's direct assistant and carried out the most important assignments of an underground organization. Professor Oscar di Fonzo organized an underground hospital for the treatment of partisans, located in the small Catholic Church of San Giuseppe. The basement of the bar belonging to Aldo Farabulini and his spouse Idran Montagna became another point of dislocation of the underground workers. In Ottavia, one of the nearest outskirts of Rome, a safe house, also used by the Fleishers, also appeared. She was supported by the Sabatino Leoni family. The wife of the apartment owner, Maddalena Rufo, got the nickname "Mother Angelina". This woman was distinguished by enviable composure. She managed to hide the underground workers when, on the second floor of the house, by the decision of the German commandant's office, several Nazi officers were stationed. The underground workers lived on the first floor, and the Nazis lived on the second floor. And it is the merit of the owners of the house that the paths of the inhabitants of the dwelling did not intersect and the stay of the underground workers was kept secret until the departure of the German officers to the next place of deployment. The peasants in the surrounding villages provided great help to the Soviet underground workers and provided partisan needs for food and shelter. Eight Italians, who sheltered Soviet prisoners of war who had fled and later housed underground workers, were awarded the high state award of the USSR, the Order of the Patriotic War, after the end of World War II.

Did not give up and did not give up

Soviet partisans and underground fighters who operated in the suburbs of Rome were engaged in a usual business for the partisans of all countries and times - they destroyed the enemy's living force, attacking patrols and individual soldiers and officers, blew up communications, spoiled the property and transportation of the Nazis. Naturally, the Gestapo was knocked down in search of unknown saboteurs who caused serious damage to the Hitlerite formations deployed in the district of Rome. On suspicion of assisting the partisans, Hitler's punishers arrested many local residents. Among them was 19-year-old Maria Pizzi - a resident of Monterotondo. In her house, the partisans always found shelter and help. Of course, this could not last for a long time - in the end, the traitor from among the local collaborators “turned in” Maria Pizzi to the Nazis. The girl was arrested. However, even under severe torture, Maria did not report anything about the activities of the Soviet partisans. In the summer of 1944, two months after her release, Maria Pizzi died - she contracted tuberculosis in the dungeons of the Gestapo. The scammers also surrendered Mario Pinchi - a resident of Palestrina, who helped the Soviet partisans. At the end of March 1944, the brave anti-fascist was arrested. Together with Mario, the Germans seized his sisters and brothers. Five representatives of the Pinchy family were brought to a cheese factory, where they were brutally murdered along with six other arrested Palestinians. The bodies of the killed anti-fascists were paraded and 24 hours hung on the central square of Palestrina. Aldo Finzi’s lawyer was also extradited to the Germans, who had previously acted as part of the Roman underground, but then moved into his mansion in Palestrin. In February, the Germans placed their headquarters in the mansion of attorney Finzi 1944. For the underground worker, this was a wonderful gift, since the lawyer was able to find out almost all the action plans of the German unit, information about which he handed over to the command of the local partisan detachment. However, the scammers soon gave the lawyer Finzi to the Hitlerite Gestapo. Aldo Finzi was arrested and brutally murdered on March 24 by 1944 in the Ardeate caves.

Often the partisans walked, literally, on the verge of death. So, on one of the evenings, Anatoly Tarasenko himself arrived in Monterotondo, the commander of partisan detachments, a prominent figure in the anti-fascist movement. He was to meet with Francesco de Zuccory, secretary of the local organization of the Italian Communist Party. Tarasenko spent the night in the house of a local resident Domenico de Battisti, but when he was going to leave in the morning, he found that a German army unit was stationed near the house. Amelia de Battisti, the wife of the owner of the house, quickly helped Tarasenko to change into her husband's clothes, after which she gave into her arms her three-year-old son. Under the guise of an Italian owner of the house, Tarasenko went out into the courtyard. The child repeated all the time in Italian "dad", which convinced the nazis that they were the owner of the house and the father of the family. So the guerrilla commander managed to avoid death and escape from the territory occupied by the Nazi soldiers.

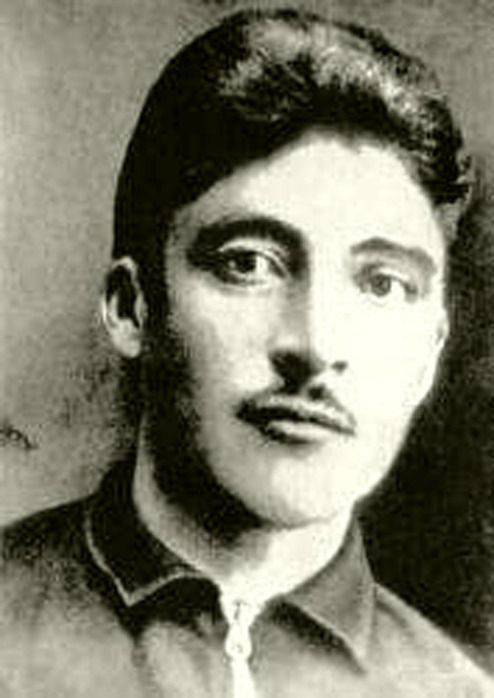

However, not always the fate was so favorable to the Soviet partisans. Thus, on the night of 28 on 29 in January of 1944, Soviet partisans arrived in Palestrina, including Vasily Skorokhodov (pictured), Nikolai Demyaschenko and Anatoly Kurepin. They were met by local Italian anti-fascists - the communists Enrico Janneti, Francesco Zbardella, Lucho and Iñazio Lena. Soviet partisans were placed in one of the houses, having supplied them with machine guns and hand grenades. The partisans were assigned the task of controlling the Galikano-Pauly road. In Palestrina, the Soviet partisans managed to live for more than a month before the collision with the Nazis. In the morning of March 9, 1944, Vasily Skorokhodov, Anatoly Kurepin and Nikolay Demyashchenko walked along the road to Galikano. Their movement behind them was covered by Peter Ilinykh and Alexander Skorokhodov. The guerrilla tried to stop the fascist patrol near the village of Fontanaone to check the documents. Vasily Skorokhodov opened fire with a pistol, killing a fascist officer and two more patrolmen. However, the other fascists who fired back managed to mortally wound Vasily Skorokhodov and Nikolai Demyashchenko. Anatoly Kurepin was killed, and Peter Ilinykh and Alexander Skorokhodov, shooting back, were able to escape. However, comrades were already in a hurry to help the partisans. In a shootout, they managed to repel the bodies of the three dead heroes from the fascists and carry them out of the way. 41-year-old Vasily Skorokhodov, 37-year-old Nikolai Demyaschenko and 24-year-old Anatoly Kurepin have forever found peace in Italian soil - their graves are still in the small cemetery of the city of Palestrina, which is 38 kilometers from the Italian capital.

However, not always the fate was so favorable to the Soviet partisans. Thus, on the night of 28 on 29 in January of 1944, Soviet partisans arrived in Palestrina, including Vasily Skorokhodov (pictured), Nikolai Demyaschenko and Anatoly Kurepin. They were met by local Italian anti-fascists - the communists Enrico Janneti, Francesco Zbardella, Lucho and Iñazio Lena. Soviet partisans were placed in one of the houses, having supplied them with machine guns and hand grenades. The partisans were assigned the task of controlling the Galikano-Pauly road. In Palestrina, the Soviet partisans managed to live for more than a month before the collision with the Nazis. In the morning of March 9, 1944, Vasily Skorokhodov, Anatoly Kurepin and Nikolay Demyashchenko walked along the road to Galikano. Their movement behind them was covered by Peter Ilinykh and Alexander Skorokhodov. The guerrilla tried to stop the fascist patrol near the village of Fontanaone to check the documents. Vasily Skorokhodov opened fire with a pistol, killing a fascist officer and two more patrolmen. However, the other fascists who fired back managed to mortally wound Vasily Skorokhodov and Nikolai Demyashchenko. Anatoly Kurepin was killed, and Peter Ilinykh and Alexander Skorokhodov, shooting back, were able to escape. However, comrades were already in a hurry to help the partisans. In a shootout, they managed to repel the bodies of the three dead heroes from the fascists and carry them out of the way. 41-year-old Vasily Skorokhodov, 37-year-old Nikolai Demyaschenko and 24-year-old Anatoly Kurepin have forever found peace in Italian soil - their graves are still in the small cemetery of the city of Palestrina, which is 38 kilometers from the Italian capital. Murder in the caves of Ardeatin

The spring of 1944 was accompanied by very persistent attempts by the Hitlerite invaders to deal with the partisan movement in the vicinity of the Italian capital. 23 March 1944, in the afternoon, a unit of the 11 Company of the 3 Battalion of the SS Bozen Regiment, stationed in Rome, moved along Rasella. Suddenly there was an explosion of terrible power. As a result of the partisan campaign, the anti-fascists managed to destroy thirty-three Nazis, 67 policemen were injured. The attack was the work of partisans from the Combat Patriotic Group, led by Rosario Bentiveña. About the daring partisan attack on the German unit was reported to Berlin - to Adolf Hitler himself. Furious Fuhrer ordered the most cruel methods to take revenge on the partisans, to carry out actions of intimidation of the local population. The German command received a terrible order - to blow up all residential areas in the area of Rasella street, and to shoot twenty Italians for each German killed. Even seasoned Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, who commanded the Nazi troops in Italy, the order of Adolf Hitler seemed excessively cruel. Kesselring did not blow up residential areas, and for each of the deceased SS men he decided to shoot only ten Italians. The direct execution of the order for the execution of the Italians was the observance of SS SS Herbert Kappler - the head of the Roman Gestapo, who was assisted by the head of the Rome police, Pietro Caruso. In the shortest possible time, a list of 280 people was formed. It included prisoners of the Roman prison who served long sentences, as well as those arrested for subversive activities.

Nevertheless, it was necessary to recruit another 50 man - so that for each of the 33 German policemen killed, ten Italians would turn out. Therefore, Kappler arrested and ordinary residents of the Italian capital. As modern historians point out, the inhabitants of Rome seized by the Gestapo and doomed to death represented a real social cut of the whole Italian society at that time. Among them were representatives of aristocratic families, and proletarians, and intellectuals - philosophers, doctors, lawyers, and inhabitants of the Jewish quarters of Rome. The age of those arrested was also very different - from 14 to 74 years. All those arrested were put in prison on Tasso Street, which was under the jurisdiction of the Nazis. In the meantime, the command of the Italian Resistance learned about the plans of the upcoming terrible reprisal. It was decided to prepare an attack on the prison and to release all those arrested by force. However, when the officers of the British and American headquarters, who communicated with the leadership of the National Liberation Committee, learned about the plan, they opposed it as being too tough. According to the Americans and the British, the attack on the prison could have caused even more brutal repression by the Nazis. As a result, the release of prisoners in the street Tasso was thwarted. The Nazis took 335 people to the Ardeatin caves. The arrested were divided into groups of five people in each, and then put on their knees, hands tied behind their backs, and shot. Then the corpses of the patriots were dumped in the Ardeatinsky caves, after which the Nazis blew up the caves with their talley swords.

Only in May 1944, the relatives of the victims, secretly making their way to the caves, brought back live flowers. But only after the liberation of the Italian capital 4 June 1944, the caves were cleared. The corpses of the heroes of the Italian Resistance were identified, and then buried with honors. Among the anti-fascists who died in the Ardeatinsky caves was a Soviet man who was buried under the name “Alessio Kulishkin” - as the Italian partisans called Alexey Kubyshkin, a young twenty-three-year-old guy born in the small Ural town of Berezovsky. However, in reality, in the Ardeatinsky caves, it was not Kubyshkin who died, but an unknown Soviet partisan. Alexey Kubyshkin and his comrade Nikolay Ostapenko, with the help of the Italian prison guard Angelo Sperry, who sympathized with the anti-fascists, were transferred to a construction team and soon escaped from prison. After the war, Alexey Kubyshkin returned to his native Ural.

The head of the Roman police, Pietro Caruso, who directly organized the killing of the arrested anti-fascists in the Ardeatyn caves, was sentenced to death after the war. At the same time, the escorts barely managed to beat off the police in a crowd of indignant Romans, who were eager to lynch the punitive and drown him in the Tiber. Herbert Kappler, who led the Roman Gestapo, after the war, was arrested and sentenced by the Italian tribunal to life imprisonment. In 1975, 68-year-old Kappler, held in an Italian prison, was diagnosed with cancer. From that time on, he was greatly facilitated by the regime of detention, in particular - they gave his wife unhindered access to the prison. In August, 1977, the wife, took Kappler out of prison in a suitcase (the ex-Gestapo dying then weighed 47 a kilogram dying of cancer). A few months later, in February 1978, Mr. Kappler passed away. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring was more fortunate. In 1947, he was sentenced to death by the English tribunal, but later the sentence was replaced by life imprisonment, and in 1952, the field marshal was released for health reasons. He died only in 1960, at the age of 74 years, until his death, remaining a staunch opponent of the Soviet Union and adhering to the idea of the need for a new "crusade" of the West against the Soviet state. The last participant of the shooting in the Ardeatinsky caves, Erich Pribka, was already extradited to Italy in our time and died at the age of one hundred years in the 2013 year, while under house arrest. Up until the middle of the 1990's. Erich Pribke, like many other Nazi war criminals, was hiding in Latin America - in Argentina.

Italy's long-awaited liberation

In the early summer of 1944, the activity of Soviet partisans in the vicinity of Rome intensified. The leadership of the Italian Resistance instructed Alexei Fleischer to create the combined forces of the Soviet partisans, which were formed on the basis of the detachments of Kolyaskin and Tarasenko. The bulk of the Soviet partisans concentrated in the Monterotondo area, where on June 6, 1944, they entered into battle with the Nazi units retreating from Monterotondo. Partisans attacked a convoy of German cars with machine-gun fire tanks. Two tanks were disabled, more than a hundred German troops were killed and 250 were taken prisoner. The city of Monterotondo was liberated by a detachment of Soviet partisans who hoisted a three-color Italian flag above the city government building. After the liberation of Monterotondo, the partisans returned to Rome. At a meeting of detachments, it was decided to make a fighting red banner, which would demonstrate the national and ideological affiliation of brave warriors. However, in warring Rome there was no matter on the red banner.

Therefore, resourceful guerrillas used to make the banner of the national flag of Thailand. From the red flag of the Siamese flag there was a white elephant, and instead there was a sickle and a hammer and a star. It is this red banner of “Thai origin” that was one of the first to hover over the liberated Italian capital. Many Soviet partisans after the liberation of Rome continued to fight in other regions of Italy.

When representatives of the Soviet government arrived in Rome, Aleksey Nikolayevich Fleisher gave them the 180 liberated from the captivity of Soviet citizens. Most of the former prisoners of war, returning to the Soviet Union, asked to join the army and continued to smash the Nazis in Eastern Europe for another year. Alexey Nikolayevich Fleisher after the war returned to the Soviet Union and settled in Tashkent. He worked as a cartographer, then retired - in general, led the way of life of the most ordinary Soviet person, in which nothing reminded of a glorious battle past and an interesting, but complex biography.

- P P 'SЊSЏ RџRѕR "RѕRЅSЃRєRёR№

- http://moypolk.ru/, http://www.lavita-odessita.com/, patriotcenter.ru

Information