Rivers of blood on the land of Bengalis. How one of the most populated states of the world fought for independence

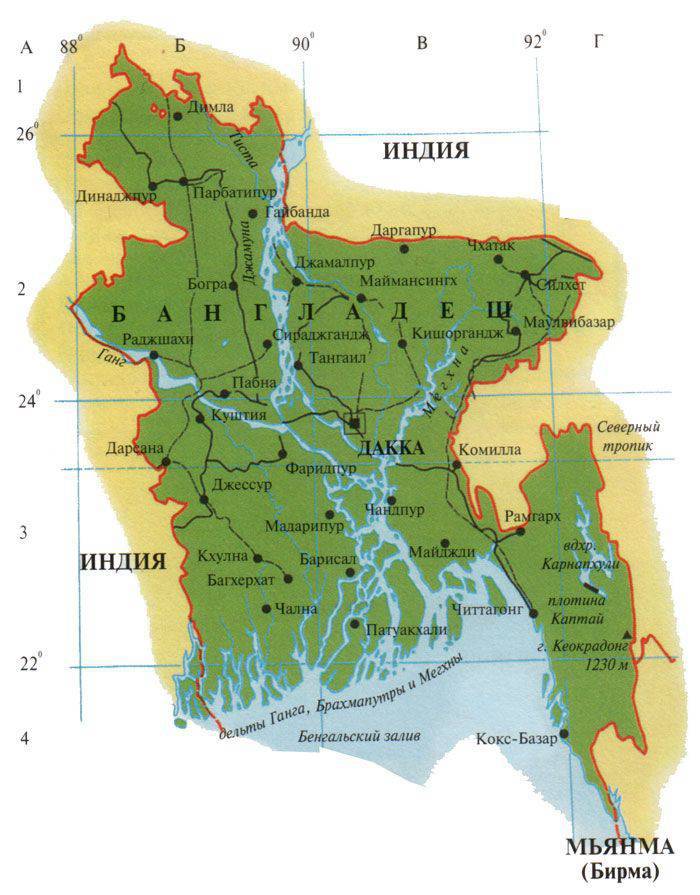

Overpopulation is added by political instability caused by the specifics of the historical and political development of the Bangladeshi state, including the peculiarities of its appearance on the world map as a sovereign state. Bangladesh is a country literally born in battle. This South Asian state had to weapons in the hands of gaining political independence, defending their right to exist in the bloody conflict between West and East Pakistan - two parts of the once united state of Pakistan that arose in 1947 as a result of the liberation and division of the former British India.

Section of Bengal and section of India

The name "Bangladesh" means "the land of the Bengalis." Bengalis are one of the most numerous peoples of the world. At least 250 million people speak Bengali, which belongs to the Indo-Aryan group of the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. Historical The Bengal region has always been conditionally divided into East and West Bengal. It turned out that Islam was established in East Bengal, while the western part of Bengal remained primarily loyal to Hinduism. Confessional differences have become one of the reasons for the desire of Bengalis - Muslims and Bengalis - Hindus to disengage. The first attempt to divide Bengal into two parts was made during the years of domination of the British colonialists on the Indian subcontinent. On October 16, 1905, the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, ordered the partition of Bengal. However, the rise of the national liberation movement in India prevented the further implementation of this plan.

In 1911, Eastern and West Bengal were reunited as a single province and continued to exist in a unified form until 1947, when Britain decided to grant political independence to British India after the Second World War. Between the British leadership, the Muslim and Hindu political elite of British India, there was an agreement that the declaration of independence would be accompanied by the creation of two independent states instead of the former colony - India itself and the Muslim state of Pakistan. The large Muslim population, concentrated in the north-west of British India and, to a lesser extent, in the north-east - just in East Bengal, sought to live apart from the Hindus and build their own Islamic statehood. Therefore, in 1947, when British India gained its independence and was divided into two states - India and Pakistan, the second division of Bengal followed - its Muslim part, East Bengal, became part of Pakistan.

It should be noted here that before the independence of India and Pakistan, Bengal was the most developed region of British India in the socio-economic sense. The favorable geographical position and developed trade relations with other regions of South and Southeast Asia led to the attention of Bengal European merchants, and later the colonialists. From about the 15th century, Islam spread among a part of the Bengal population, mainly concentrated in the eastern regions of Bengal. Representatives of the lower castes who sought to get rid of discrimination on the basis of caste affiliation, as well as urban strata, influenced by Arab merchants with whom they had to contact, entered Islam. Unlike the Northwest Hindustan, on the territory of which Pakistan subsequently formed, in Bengal there was a small percentage of Arabs, Persians, Turks, and Mongols. If the Arab-Persian-Turkic component in the culture and history of Pakistan is clearly visible, then Bengal is a purely “Indian” region, in which the Islamization of society was somewhat different.

For the Bengali population in the framework of British India was characterized by a kind of Bengali nationalism, uniting representatives of various faiths - both Hindus and Muslims. The unifying factor was the linguistic community of Bengalis. Bengali is one of the most common and developed languages of India, which played in the northeastern parts of the country the role of "lingua franca", similar to that played by the Hindi language for the Hindu population of North-West India, and Urdu for the Muslims of the future Pakistan. Discontent with British colonial rule was another factor consolidating the Hindus and Muslims of Bengal in their desire to free themselves from the yoke of the British Empire. In addition, the Bengalis were traditionally one of the most educated nations of India, from which the British recruited colonial officials and who, therefore, had the most adequate understanding of modern politics and economics.

The division of British India into Hindu and Muslim states was accompanied by a sharp deterioration in the already problematic relations between Hindus and Muslims. In the first place, the conflicts that arose were associated with the movement of the Hindu population from Pakistan and the Muslim from India. Violent displacements affected at least 12 millions of Hindus and Muslims and took place in both northwest and northeast India. East Bengal, populated mainly by Muslims, became part of the state of Pakistan, which meant the eviction of millions of Hindus from its territory, including those with considerable property. Naturally, this caused conflicts between the Hindu and Muslim populations. However, as the independent Islamic state of Pakistan became established, internal contradictions began to grow between its population, despite confessional unity.

Pakistan was a two-part post-war period. Western Pakistan included most of Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan provinces, the warlike Pashtun tribes of the North-West Frontier Province. East Pakistan was formed in East Bengal, with its center in the city of Dhaka, and was located at a great distance from West Pakistan. Naturally, there were huge differences between the people of East and West Pakistan. The population of Western Pakistan has historically been greatly influenced by Iranian culture, the Urdu language spoken in Western Pakistan has absorbed large layers of borrowing from Farsi, Arabic, and Turkic languages of Central Asia. East Pakistan, populated by Bengali Muslims, remained culturally more “Indian”, with significant cultural and, more importantly, linguistic differences between it and Western Pakistan.

Fight for Bengali

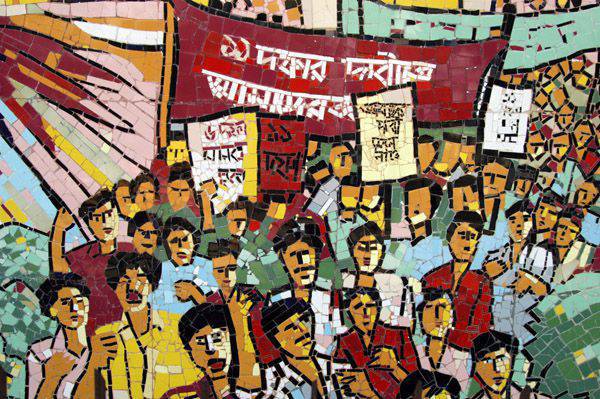

Bengali, also developed and ancient, competed with Urdu. Bengal Muslims did not consider themselves obliged to learn Urdu as the state language of Pakistan, as they were fully satisfied with the developed level and prevalence of Bengali. Bengali was spoken by a significant part of the population of Pakistan, but it never received the status of the state language. In 1948, the leadership of Pakistan, which was dominated by representatives of the West Pakistan elite, declared Urdu to be the only official language in the country. Urdu became the official language of state documentation and institutions in the territory of East Pakistan, which caused outrage of the local population. After all, the overwhelming majority of the Bengali people did not speak Urdu, even the educated Bengalis spoke Bengali and English, but they had never before considered it necessary to study Urdu, spread thousands of kilometers from Bengal. The Bengali elite, not knowing Urdu, turned out to be isolated from the possibility of participating in the political life of a united Pakistan, could not hold public office and make a career in public and military service. Naturally, the current situation has led to mass demonstrations by residents of East Pakistan in defense of the Bengali language. The Bengali language status movement (“Bhasha Andolon” - Language movement) was gaining momentum in East Pakistan.

The first cultural and political organization, which set itself the goal of fighting for the state status of the Bengali language, was created almost immediately after the division of British India - in December 1947. Professor Nurul Haq Buyian headed Rastrabhas Sangram Parishad, and later MP Shamsul Haq created the Committee to promote Bengali as a state language. However, the idea of proclaiming Bengali as the second state language of Pakistan was opposed by representatives of the Western Pakistani political elite, who argued that bilingualism would lead to an increase in separatist and centrifugal tendencies, and in fact were afraid of competition from the Bengali elite - educated people, many of whom had administrative experience during the colonial period, and the only barrier to the promotion of which in the service was their ignorance of the Urdu language.

11 March 1948 at the University of Dhaka, the capital of East Pakistan, began a strike of students protesting against depriving Bengali of official status. During the protest, clashes with police occurred, student leader Mohammed Toaha was hospitalized after being injured while trying to take away weapons from a police officer. In the afternoon of March 11 a rally was organized against the brutal, according to students, methods of the police. Students moved to the house of Khawaji Nazimuddin, but were stopped at the courthouse. There was a new clash with the police, during which the police wounded several people. 19 March 1948 was brought to Dhaka by Muhammad Jinn, the governor-general of Pakistan, who declared that the claims of declaring Bengali as the state language of Pakistan and that they were lobbying for Pakistani statehood were invented. In his statement, Jinna stressed that only Urdu expresses the spirit of Islamic Pakistan and only Urdu will remain the only official language of the country.

The next wave of protests ensued in 1952. Bengali students reacted harshly to the latest statement by the new governor-general of Pakistan, Hawaji Nazimuddin, about preserving Urdu in the country's only state language. 27 January 1952 was formed at the University of Dhaka by the Central Committee for Language Issues under the leadership of Abdul Bhashani. February 21 began a protest announced by the committee.

Students gathered outside the university building and clashed with the police. Several people were arrested, after which riots broke out in the city. Several people were killed by police bullets who dispersed an unauthorized demonstration. The next day, the February 22 riots intensified. In Dhaka, more than 30 000 protesters gathered and set fire to government offices. The police again opened fire on the protesters. Several activists died and a nine-year-old boy present at the demonstration.

Students gathered outside the university building and clashed with the police. Several people were arrested, after which riots broke out in the city. Several people were killed by police bullets who dispersed an unauthorized demonstration. The next day, the February 22 riots intensified. In Dhaka, more than 30 000 protesters gathered and set fire to government offices. The police again opened fire on the protesters. Several activists died and a nine-year-old boy present at the demonstration. On the night of February 23, students erected the Monument to the Martyrs, which three days later, February 26, was destroyed by police. The Pakistani government imposed severe censorship in the media without reporting the number of protesters and the victims of the police. The official version explained what was happening with the intrigues of the Hindus and the communist opposition. However, the brutal suppression of protests in Dhaka failed to defeat the public movement for the state status of the Bengali language. February 21 Bengalis began to celebrate as "Day of the Martyrs", arranging spontaneous weekends in institutions. In 1954, the Muslim League, which came to power, decided to give official status to the Bengali language, which in turn caused massive protests of Urdu supporters. Nevertheless, certain steps towards recognizing the rights of the Bengali language have been taken. 21 February 1956, the next "Day of the Martyrs" was first held in East Pakistan without police repression. 29 February 1956 The Bengali language was officially proclaimed the second language of Pakistan, in accordance with which changes were made to the text of the Pakistani constitution.

However, the recognition of Bengali as the second official language of the country did not entail the normalization of relations between West and East Pakistan. Bengalis were unhappy with discrimination in government bodies and law enforcement agencies by people from West Pakistan. In addition, they were not satisfied with the amount of financial assistance provided by the Government of Pakistan for the development of the eastern region. In East Pakistan, autonomist sentiment was growing and the demand for Bengali nationalists to rename East Pakistan to Bangladesh, that is, the “Bengalis Country”, led to further growth of the protest movement. Bengalis were convinced that West Pakistan deliberately discriminated against the eastern region and would never allow the position of Bengalis to be strengthened in state bodies. Accordingly, among the Bengali people, there was growing conviction in the need to achieve autonomy within Pakistan, while the most radical Bengali nationalists demanded the creation of a separate Bengali state.

War for independence. Mukti Bahini

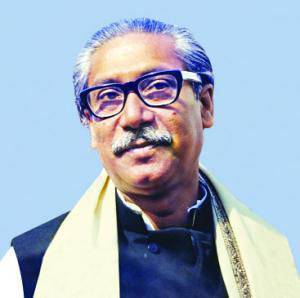

The drop that broke the patience of Bengalis was cyclones, which caused a terrible disaster for East Pakistan. As a result of cyclones in 1970, over 500 thousands of people in East Pakistan died. Bengal politicians blamed the Pakistani government for not providing sufficient funds to prevent such large-scale consequences of the tragedy and were in no hurry to rebuild damaged infrastructure and help affected families. The political situation in East Pakistan has worsened due to the fact that the central authorities prevented Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the head of the People’s League (Awami League) of East Pakistan, which won the parliamentary elections.

Mujibur Rahman (1920-1975), a Bengali Muslim who from his youth participated in the movement for the liberation of Pakistan, was an activist of the Muslim League. In 1948, he participated in the creation of the Muslim League of East Pakistan, then he was one of the leaders of the People’s League. After the military coup in Pakistan in 1958, the military government arrested Mujibur Rahman. From the 23 years of the existence of a unified Pakistan, 12 years of Mujibur Rahman spent in custody. In 1969, he was released after another term of imprisonment, and in 1970, the People’s League won a majority in the parliamentary elections in East Pakistan. Mujibur Rahman was to form the government of East Pakistan, but the central leadership put all kinds of obstacles in this.

Mujibur Rahman (1920-1975), a Bengali Muslim who from his youth participated in the movement for the liberation of Pakistan, was an activist of the Muslim League. In 1948, he participated in the creation of the Muslim League of East Pakistan, then he was one of the leaders of the People’s League. After the military coup in Pakistan in 1958, the military government arrested Mujibur Rahman. From the 23 years of the existence of a unified Pakistan, 12 years of Mujibur Rahman spent in custody. In 1969, he was released after another term of imprisonment, and in 1970, the People’s League won a majority in the parliamentary elections in East Pakistan. Mujibur Rahman was to form the government of East Pakistan, but the central leadership put all kinds of obstacles in this. 26 March 1971. Pakistan’s President General Yahya Khan ordered the arrest of Mujibur Rahman. On the night of 25 in March of 1971, Operation “Searchlight” began to “establish order in East Pakistan”. The leadership of East Pakistan, represented by the governor of Sahabzad Yakub Khan and the vice-governor of Syed Mohammad Ahsan, refused to participate in an armed operation against the civilian population and was dismissed. Lieutenant-General Mohammed Tikka Khan was appointed Governor of East Pakistan. The plan for Operation Projector was developed by Major General Hadim Hussein Reza and Rao Farman Ali. In accordance with the plan of operations, troops from Western Pakistan were to disarm the paramilitary forces and the police, staffed by Bengalis. Thousands of police officers in East Pakistan - Bengali nationals as having military training and experience with weapons were supposed to be shot. Pakistani commandos led by General Mittha arrested Mujibur Rahman.

Troops under the command of Major General Rao Farman Ali launched an offensive against Dhaka, and units of Major General Hadim Hussein Reza carried out a sweep of the countryside around the capital. Lieutenant-General Tikka Khan, who oversaw the operation, subsequently received the nickname “The Butcher of Bengal” for cruelty to the civilian population of East Pakistan. Nevertheless, despite the brutality of the Pakistani troops, the Bengalis began to organize resistance. 27 March 1971 Major Zaur Rahman read the appeal of Mujibur Rahman on the proclamation of the independence of the state of Bangladesh. The defenders of Bangladesh's sovereignty began a guerrilla war, since all the cities of the country were occupied by Pakistani troops, who brutally suppressed any opposition activity. The Pakistani military killed, according to various estimates, from 200 thousands to 3 million Bangladesh residents. Another 8 million people were forced to leave their native land and flee to the adjacent states of neighboring India.

India immediately after the proclamation of independence of Bangladesh declared its full support for the new state, acting primarily in the interests of weakening Pakistan. In addition, the arrival of millions of refugees in India created serious social problems, so the Indian leadership was interested in the early normalization of the political situation in East Pakistan - Bangladesh. With the support of India, guerilla forces "Mukti Bahini" (Liberation Army) acted on the territory of Bangladesh.

East Bengal was divided into 11 partisan zones, each headed by a Bengali officer with experience in the Pakistani army. In addition, partisan formations created their own air forces and river fleet. The Partisan Army Air Force consisted of 17 officers, 50 technicians, 2 aircraft and 1 helicopter, but despite the small number they carried out 12 effective actions against the Pakistani army. The Mukti Bahini river fleet at the beginning of its military journey consisted of 2 ships and 45 sailors, but also conducted a large number of operations against the Pakistani Navy fleet.

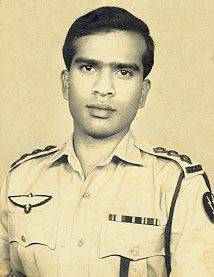

East Bengal was divided into 11 partisan zones, each headed by a Bengali officer with experience in the Pakistani army. In addition, partisan formations created their own air forces and river fleet. The Partisan Army Air Force consisted of 17 officers, 50 technicians, 2 aircraft and 1 helicopter, but despite the small number they carried out 12 effective actions against the Pakistani army. The Mukti Bahini river fleet at the beginning of its military journey consisted of 2 ships and 45 sailors, but also conducted a large number of operations against the Pakistani Navy fleet. The guerrilla movement in Bangladesh was not politically united and united both the Bengali nationalists, who held the right-wing positions, and the leftists, the socialists and the Maoists. One of the most popular guerrilla commanders was Lieutenant Colonel Abu Taher (1938-1976). A native of Assam province, he was a Bengali by birth. After graduating from college in 1960, the city of Abu Taher as a candidate officer joined the Pakistani army. In 1962, he was promoted to second lieutenant, and in 1965, he was enlisted in the elite unit commando. As part of the Pakistani commandos, Abu Taher took part in the Indo-Pakistani 1965 war in Kashmir, after which he was sent to refresher courses on the guerrilla war in Fort Benninge in the United States.

At the end of July 1971, Captain Abu Taher, together with Major Abu Mansur, Captains Dalim and Ziyauddin, deserted from the Pakistani army and crossed the border in the Abbotabad area, penetrating into India. After a two-week check, Abu Taher was placed at the disposal of the command of the Bangladesh Liberation Army, from which he immediately received the rank of major. Abu Taher was appointed commander of one of the partisan units. 2 November 1971 Taher lost a leg in a grenade explosion and was sent to India for treatment.

At the end of July 1971, Captain Abu Taher, together with Major Abu Mansur, Captains Dalim and Ziyauddin, deserted from the Pakistani army and crossed the border in the Abbotabad area, penetrating into India. After a two-week check, Abu Taher was placed at the disposal of the command of the Bangladesh Liberation Army, from which he immediately received the rank of major. Abu Taher was appointed commander of one of the partisan units. 2 November 1971 Taher lost a leg in a grenade explosion and was sent to India for treatment. The landscape and climate of Bangladesh contributed to the success of Mukti Bahini. The immigrants from Western Pakistan, who constituted the overwhelming majority of the Pakistani contingent sent to Bangladesh, did not have experience in fighting in the jungle and anti-partisan struggle, which the guerrillas effectively used in confronting the regular Pakistani army. The first commander of the Liberation Army was Zaur Rahman, and in April 1971 was replaced by Colonel Mohammed Osmani, who took command of all the armed forces of the 17 guerrillas on April 1971. combat experience. A graduate of the State Pilot School in Sylhet and the Muslim University in Aligarh, he began his civil service career in British India, but with the start of World War II he entered military service. In 53, he graduated from the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun and, with the rank of second lieutenant, he began serving as an artillery officer in the British Indian Army. Osmani fought on the Burma Front, where he quickly received the rank of captain - in 1918 and the major - in 1984. After the war, Mohammed Osmani graduated from the course of staff officers in the UK and was recommended for assignment to the rank of lieutenant colonel. When the partition of British India occurred and Pakistan gained state independence, Osmani was enlisted for further service in the emerging Pakistani armed forces.

In the Pakistani army, he became the chief adviser to the chief of the General Staff. But then Osmani moved from headquarters to army units and in October 1951 became the commander of the 1 East Boengal regiment stationed in East Pakistan. Here he began to introduce the Bengali culture into the life of the regiment, which caused rejection of the higher Pakistani command. Lt. Col. Osmani was transferred to a subordinate position - commander of the 9 battalion of the 14 Punjab regiment, but then was appointed deputy commander of the East-Pakistani riflemen.

In 1956, the city of Osmani was promoted to colonel, and in 1958, he was appointed Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Pakistani Army, then Deputy Head of the Military Planning Division. Serving in the Pakistani General Staff, Colonel Osmani in every way sought to strengthen the defense capability of East Pakistan, increasing the number and number of Bengali armed units within the Pakistani army. 16 February 1967 Osmani retired. After that, he was engaged in political activities in the composition of the People's League. It was Osmani who was the leading link in connection with Bengali nationalist politicians with army officers of Bengali origin. 4 on April 1971 of Osmani appeared in the 2 East Bunghal Regiment, and on April 17 became the commander-in-chief of the Bangladesh Liberation Army. It was the vast combat experience of Colonel Osmani that helped the Bengali people form an effective partisan movement against which the regular Pakistani troops were powerless.

In 1956, the city of Osmani was promoted to colonel, and in 1958, he was appointed Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Pakistani Army, then Deputy Head of the Military Planning Division. Serving in the Pakistani General Staff, Colonel Osmani in every way sought to strengthen the defense capability of East Pakistan, increasing the number and number of Bengali armed units within the Pakistani army. 16 February 1967 Osmani retired. After that, he was engaged in political activities in the composition of the People's League. It was Osmani who was the leading link in connection with Bengali nationalist politicians with army officers of Bengali origin. 4 on April 1971 of Osmani appeared in the 2 East Bunghal Regiment, and on April 17 became the commander-in-chief of the Bangladesh Liberation Army. It was the vast combat experience of Colonel Osmani that helped the Bengali people form an effective partisan movement against which the regular Pakistani troops were powerless. Third Indo-Pakistani War and the Liberation of Bangladesh

From the very beginning of the hostilities, Bangladeshi partisans received comprehensive assistance from India, not only supplying them with weapons, but also sending a significant contingent of Indian troops to participate in the hostilities under the guise of Bengal partisans. India’s aid to Bangladeshi partisans has seriously worsened relations between India and Pakistan. The Pakistani military leadership concluded that while India supports the partisan movement in East Bengal, it will not be possible to defeat it. Therefore, it was decided to launch attacks by the Pakistani Air Force against Indian military installations. On December 3, 1971, the Pakistani Air Force launched airstrikes on Indian airfields during Operation Genghis Khan. An example for the Pakistanis was the Israeli strike aviation in the Arab countries during the Six Day War of 1967. As you know, in those days, the Israeli Air Force with lightning strikes destroyed the military aircraft of the Arab countries that fought against Israel. But the Pakistani Air Force failed to destroy Indian aviation at airfields.

The Third Indo-Pakistani war began. 4 December 1971 was mobilized in India. Despite the fact that Pakistan tried to go on the offensive on the Indian positions on two fronts - east and west, the forces of the parties were unequal. During the battle of Lonneval 5-6 in December 1971 of one company of the 23 battalion of the Punjab regiment, the Indian army managed to repel the attack of the entire brigade of the Pakistani army - the 51 of the infantry brigade. The equipment of the brigade was destroyed from the air by Indian bomber aircraft. This success was followed by other effective actions of the Indian army. The Soviet Union provided weighty assistance to the Bangladeshi independence fighters. The minesweepers of the 12 expedition of the USSR Navy under the command of Rear Admiral Sergei Zuyenko were busy clearing the port of Dhaka from the mines left by the Pakistani fleet. After two weeks of hostilities, the Indian armed forces advanced deep into Bangladesh and surrounded the capital city of Dhaka. Over 93 000 soldiers and officers of the Pakistani army were captured in India and Bangladesh.

On December 16, the commander of Pakistani troops in East Pakistan, General Niyazi, signed the act of surrender. The next day, December 17 India announced the cessation of hostilities against Pakistan. Thus ended the Third Indo-Pakistani War, which coincided with the War of Independence of the State of Bangladesh. 16 December 1971 in Pakistan was released by Mujibur Rahman, who left for London and January 10. 1972 arrived in Bangladesh. He was proclaimed prime minister of the government of the independent People’s Republic of Bangladesh 2 a day after returning to the country - January 12 1972. In Pakistan itself, the shameful defeat in the war led to a change of government. General Yahya Khan resigned, and his successor, Zulfiqar Bhutto, three years later offered an official apology to the people of Bangladesh for the crimes and atrocities committed by the Pakistani army in Bengali land.

The first years of independence

The first years of independence of Bangladesh were held under the slogans of the same democratic reforms. The assistance provided by Bangladesh by India, China and the USSR served as a guarantee of the “left path” of Bangladesh statehood. Mujibur Rahman proclaimed nationalism, democracy, socialism and secularism the four principles of building a sovereign Bangladeshi state. In March 1972, he visited the USSR on an official visit. However, within the Bangladeshi national movement, the struggle between representatives of different political trends did not stop. Mujibur Rahman, the father of Bangladeshi’s statehood, in spite of the declared socialist and secularist slogans, in practice was inclined to cooperate with the Islamic world.

Part of the Bangladeshi left-wing radicals did not agree with the regime established by Mujibur Rahman and sought to further continue the national liberation revolution and turn it into a socialist revolution. So, in 1972-1975. in the Chittagong region, the proletarian party of East Bengal under the leadership of Siraj Sikder (1944-1975) launched a guerrilla war.

A graduate of the East Pakistan University of Technology and Technology 1967, Siraj Sikder still actively participated in the Student Union of East Pakistan in his student years, and on January 8 1968 founded the underground East Bengal Labor Movement (“Purba Bangla Sramik Andolon”). This organization sharply criticized the existing pro-Soviet Communist parties accused of revisionism, and set as its goal the creation of a Revolutionary Communist Party in Bangladesh.

A graduate of the East Pakistan University of Technology and Technology 1967, Siraj Sikder still actively participated in the Student Union of East Pakistan in his student years, and on January 8 1968 founded the underground East Bengal Labor Movement (“Purba Bangla Sramik Andolon”). This organization sharply criticized the existing pro-Soviet Communist parties accused of revisionism, and set as its goal the creation of a Revolutionary Communist Party in Bangladesh. According to Siraj Sikder and his like-minded people, East Bengal was turned into a colony by Pakistan, so only the struggle for independence will help the Bangladeshi people to break free from the oppression of the Pakistani bourgeoisie and feudal lords. The People’s Republic of East Bengal saw Siraj Sikder see free from American imperialism, Soviet “social-imperialism” and Indian expansionism. During the war of independence, partisans under the command of Siraj Sikder acted in the south of the country, where the Proletarian East Bengal Party (Purba Bangla Sarbahar Party) was created as a revolutionary organization focused on the ideas of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. Siraj Sikder sought to cultivate a revolutionary popular movement in Bangladesh on the basis of the Mukti Bahini guerrilla movement. It was for this purpose that the Maoists, led by Sikder, continued the war in the mountains of Chittagong even after the end of the struggle for independence. In 3, Siraj Sikder was arrested by the Bangladesh intelligence service in Khali Shahr in Chittagong and 1971 in January 1975 was killed in a police station.

The activities of Mujibur Rahman displeased part of the Bangladeshi officers and 15 August 1975 in the country there was a military coup. Mujibur Rahman, all his associates and all family members in Bangladesh, including his grandson and ten-year-old son, were killed. The military regime moved to brutal repression against the left movement. This infuriated many servicemen, among whom the participants in the war of liberation, who were sympathetic to leftist ideas, prevailed. One of the leaders dissatisfied with the policy of the military regime was Abu Taher. After the amputation of his leg, he returned to Bangladesh and was reinstated in military service with the rank of lieutenant colonel. In June, 1972 Taher was appointed commander of the 44 Infantry Brigade. Abu Taher held leftist views and shared the ideas of modernizing the Bangladeshi army, modeled on the People’s Liberation Army of China. Resigning from military service due to political differences with the command, Lieutenant Colonel Abu Taher became the leading activist of the National Socialist Party of Bangladesh. After the murder of Mujibur Rahman, he continued his left-wing agitation in the army and on November 3 1975 led a socialist uprising of soldiers and noncommissioned officers of the Bangladeshi army. Nevertheless, the military regime managed to suppress the uprising and Lieutenant Colonel Taher was convicted by the military tribunal 24 November 1975. The hero of the liberation war was sentenced to death and 21 July 1976 was hanged.

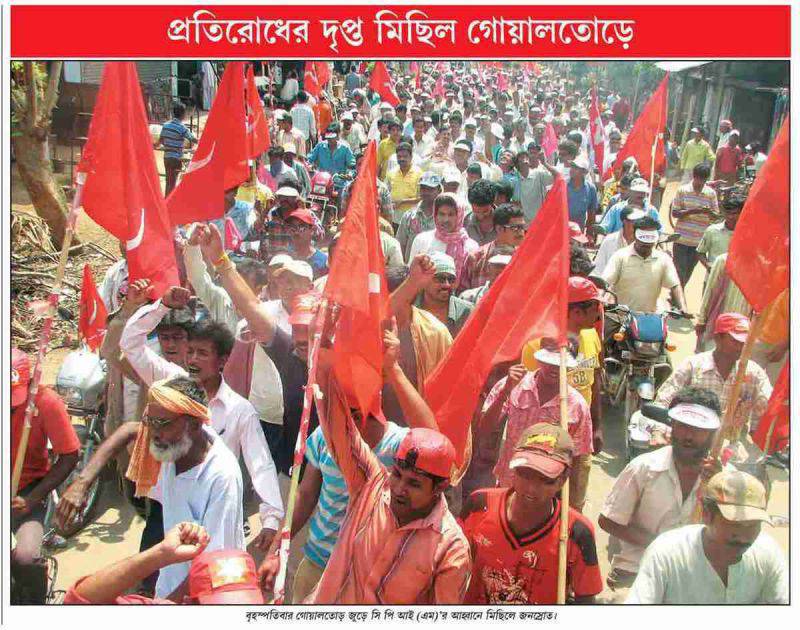

Further political history of Bangladesh is not highly political stable. During the forty years that have passed since the murder of Mujibur Rahman, the country was repeatedly shaken by military coups, the military governments replaced each other. The main vector of opposition is observed along the line “secular nationalists - Islamic radicals”. At the same time, the allies of secular nationalists are leftist and secularist forces. Nevertheless, part of the left is negatively disposed towards all political parties in the country. The Maoists from the Proletarian Party of Bangladesh and the Maoist Bolshevik movement for the reorganization of the Proletarian Party of East Bengal are fighting partisan in several parts of the country, periodically organizing mass riots in the cities of Bangladesh. Another threat to the state is observed by religious fundamentalists who insist on raising the importance of religion in the life of the country and establishing the Islamic state in Bangladesh.

Information