Cossacks and the February Revolution

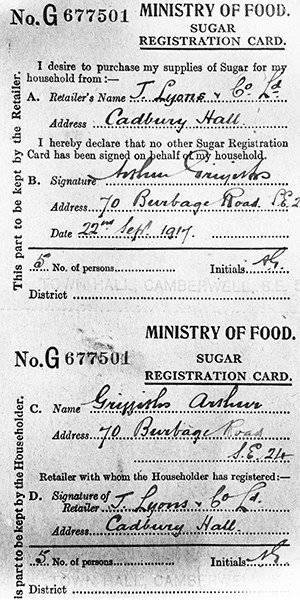

Fig. 1 English Sugar Food Card from 22 September 1914

Fig. 1 English Sugar Food Card from 22 September 1914It must be said that the disciplined European peasants, be it Jacques, John or Fritz, despite all the difficulties, continued to regularly pay draconian innodal taxes. Other demonstrated our Ostap and Ivan. The 1916 harvest of the year was good, but rural producers, in the context of military inflation, began to massively hold onto food, expecting even greater price increases. Avoiding taxes is a centuries-old misfortune of our commodity producer. In hard times, this “popular fun” invariably provokes the state to take repressive measures, which the owner later regrets. In our stories This “fun” led to many troubles, not only to the introduction of a surplus in 1916, but also became a decisive moment for carrying out forced collectivization after the failure of the peasants (and not only fists) of the tax bread in 1928 and 1929. What is the end for their small and medium businesses, their current "fun" with state tax authorities is still unknown, but most likely, the same. But this is a lyrical digression.

And at that time, in order to stabilize the supply of cities and the army with food, the tsarist government in the spring of 1916 also began to introduce a rationing system for some products, and in the fall it was forced to introduce an additional development (some “enlightened” anti-communists still believe that the Bolsheviks introduced it). As a result, due to higher prices, there was a noticeable decline in the standard of living in the city and in the countryside. On the food crisis overlaid confusion in transport and in public administration. Due to many failures, abundantly flavored with malicious rumors and anecdotes, there was an unprecedented and unheard of since the Time of Troubles, the decline of the moral authority of the royal power and the royal family, when not only cease to be afraid of power, but they even begin to despise it and openly laugh at it . A “revolutionary situation” has developed in Russia. Under these conditions, part of the courtiers, state and political figures, for the sake of their own salvation and the satisfaction of their ambitions, inspired a coup d'état that led to the overthrow of the autocracy. Then, as expected, this coup was called the February Revolution. It happened, frankly, at a very inopportune moment. General Brusilov recalled: “... as far as I am concerned, I was well aware that the 1905 revolution of the year was only the first act, which the second had to inevitably follow. But I prayed to God that the revolution began at the end of the war, because it is impossible to fight and revolution at the same time. It was absolutely clear to me that if the revolution starts before the end of the war, we will inevitably lose the war, which will lead to the fact that Russia will crumble. ”

How was the striving of society, aristocracy, officials and high command to change the state system and the sovereign's abdication? Almost a century later, in essence, almost no one objectively answered this question. The reasons for this phenomenon lie in the fact that everything written by the direct participants in the events not only does not reflect the truth, but more often distorts it. One has to take into account that the writers (for example, Kerensky, Milyukov, or Denikin) understood well after a while what fate and history had given them the terrible role. They had a large share of the blame for what happened, and they, naturally, described the events, portraying them in order to find an excuse and explanation for their actions, as a result of which state power was destroyed and the country and the army were turned into anarchy. As a result of their actions in the country by October 1917, no power remained, and those who played the role of rulers did everything to ensure that not only any power emerged, but even that appearance. But first things first.

The foundation of the revolution for the overthrow of the autocracy began to be laid for a long time. Beginning from the 18th century and up to the 20th century, the rapid development of science and education in Russia took place. The country experienced a silver age in the heyday of philosophy, education, literature and the natural sciences. Along with enlightenment in the minds and souls of educated Russians, materialistic, social and atheistic views, often in their most perverse ideological and political form, began to be cultivated. Revolutionary ideas penetrated into Russia from the West and took peculiar forms under Russian conditions. The economic struggle of workers in the West was a struggle against the inhumanity of capitalism and for the improvement of economic working conditions. And in Russia, revolutionaries demanded a radical breakdown of the entire existing social order, the complete destruction of the foundations of state and national life, and the organization of a new social order based on imported ideas, refracted through the prism of their own imagination and unrestrained social and political fantasy. The main feature of the Russian revolutionary leaders was the complete absence of constructive social principles in their ideas. Their main ideas sought the same goal - the destruction of social, economic, social foundations and the complete denial of "prejudices", namely morality, morality and religion. This ideological perversity was described in some detail by the classics of Russian literature, and the brilliant analyst and ruthless preparator of Russian reality, F.M. Dostoevsky christened her "devilry." But especially many disbelievers-atheists and nihilists-socialists appeared in the late XIX and early XX centuries among students, students and young workers. All this coincided with a population explosion. The birth rate was still high, but with the development of the Zemstvo health system, infant mortality decreased significantly (although by today's standards it was still huge).

The result was that by 1917, ¾ of the country's population was younger than 25 years, which determined the monstrous immaturity and lightness of the actions and judgments of this mass and no less monstrous contempt for the experience and traditions of previous generations. In addition to the 1917 year, about 15 millions of these young people went through the war, gaining considerable experience and authority there, and often also honor and glory. But having acquired maturity in status, they could not in the course of this short time acquire maturity of mind and everyday experience, while remaining virtually youthful. But they stubbornly bent their line, inflated into their ears by rashristannymi revolutionaries, regardless of the experienced and wise old people. With ingenious simplicity, this problem, in the Cossack society, was exposed by M. Sholokhov in “The Quiet Don”. Melekhov-father, returning from the farm circle, grumbled and swore at the returning heavily "reddened" bellowing front-line soldiers. “Take a whip, and flog these gorlopanov. Well, why not, where to us. They are now an officer, conscript, crusaders ... How to smack them? At the beginning of the twentieth century, John of Kronstadt spoke of the dictatorship of the “autocracy of mind” over the soul, spirituality, experience and faith: “Faith in God and truth disappeared and was replaced by faith in the human mind, the seal became isolated, nothing sacred or honorable became for it, except cunning pen, imbued with the poison of slander and ridicule. The intelligentsia has no love for the motherland, it is ready to sell it to foreigners. Enemies are preparing the decomposition of the state. There is no truth anywhere, the Fatherland is on the verge of destruction. ”

The atroists, who were spoiled by the progressive progressists, managed to quickly and corrupt the youth and educated classes, then these ideas, through teachers, began to penetrate the peasant and Cossack masses. Disorder and hesitation, nihilistic and atheistic moods embraced not only educated classes and students, but also penetrated into the environment of seminarians and clergy. Atheism takes root in schools and seminaries: from 2148 graduates of 1911 seminaries of the year, all 574 people ordained priests. In the midst of the priests themselves, heresy and sectarianism flourish in wild color. Through the priests, teachers, and the press, the great and terrible bedlam, this indispensable harbinger and companion of any great Troubles or Revolution, firmly settle in the heads of many people. It is not by chance that one of the leaders of the French Revolution, Camille Desmoulins, said: "The priest and teacher begin the revolution, and the executioner ends." But such a state of mind is not something exotic or extraordinary for Russian reality, such a situation can exist in Russia for centuries and it does not necessarily lead to a Trouble, but only creates an ideological fornication in the heads of the educated classes. But only if Russia is headed by a tsar (leader, secretary general, president - no matter what he is called), who is able to consolidate most of the elite and the people on the basis of a healthy state instinct. In this case, Russia and its army are capable of making disproportionately great difficulties and trials, rather than reducing a soldier's meat ration by half a pound or replacing a part of troops with boots for boots with windings. But it was not the case.

The prolonged war and the absence of a real leader in the country catalyzed all negative processes. Back in 1916, 97% of soldiers and Cossacks took holy communion in combat positions, and at the end of 1917, only 3%. The gradual cooling of faith and royal power, anti-government sentiments, the lack of a moral and ideological core in the heads and souls of people were the main causes of all three Russian revolutions. Anti-clerical sentiment spread in the Cossack villages, although not as successfully as in other places. So in the village. In 1909, Kidyshevsky, a local priest Danilevsky, in the Cossack's house, threw off two portraits of the king, about which a criminal case was initiated. In the OKV (Orenburg Cossack Army), local liberal newspapers such as Kopeyka, Troichanin, Steppe, Kazak and others provided abundant food for spiritual debauchery. But in the Cossack villages and villages, the destructive influence of atheists, nihilists and socialists was opposed by old bearded men, atamans and local priests. They fought hard for many years for the minds and souls of simple Cossacks. At all times, the classes of priests and Cossacks were the most spiritually resistant. However, socio-economic reasons did not change the situation for the better. Many Cossack families, having sent 2-3 sons into the army, fell into need and ruin. The number of poor people in the Cossack villages multiplied and at the expense of landless yards living among the Cossacks from other cities. Only in the OKW there were more than 100 thousands of people of the non-aristocratic class. Having no land, they were forced to rent it from the villages, from wealthy and horseless Cossacks and pay rent from 0,5 to 3 rubles. for tithe. Only in 1912, 233548 rubles of land rent, more than 100 thousand rubles of "planted pay" for the construction of non-resident houses and outbuildings on military lands, came to the OKV coffers. They paid non-residents for the right to use pastures, forests and water resources. In order to make ends meet, the nonresident and Cossack poor batrailed on wealthy Cossacks, which contributed to the consolidation and rallying of the poor, which later, during the revolution and civil war, brought its bitter fruits, helped the Cossacks to split into opposing camps and push them into a bloody fratricidal war.

All this created favorable conditions for anti-government and anti-religious sentiments, which was used by socialists and atheists — intellectuals, students, and students. Among the Cossack intelligentsia appear preachers of the ideas of godlessness, socialism, class struggle and “petrel revolution”. And, as is usually the case in Russia, the offspring of very wealthy classes are the main instigators, nihilists and foundations subversive. One of the first Cossack revolutionaries of the OKV was a native of the richest gold-mining village of Uisk, the son of a rich gold-miner merchant Peter P. Maltsev. From the 14 summer age, a high-school boy at the Trinity Gymnasium joins the protest movement, publishes the magazine Tramp. Expelled from many universities, after three years in jail, he in exile establishes communication and correspondence with Ulyanov and has since been his main opponent and consultant on the agrarian issue. Not far from him went his half-brother, rich gold producer Stepan Semenovich Vydrin, spawn of a whole line of future revolutionaries. At an equally young age, the brothers Nikolai and Ivan Kashiriny from Verkhneuralskaya, the future red commanders, embarked on the slippery slope of revolutionaries. The sons of the stanitsa teacher, and then the ataman, received a good secular and military education, both very successfully graduated from the Orenburg Cossack School. But in 1911, the court of officer honor established that "centurion Nikolai Kashirin is inclined to assimilate bad ideas and enforce them" and the officer was dismissed from the regiment. Only in 1914, he was again called to the regiment, he fought bravely and in a short time won the 6 royal awards. But the officer still conducted revolutionary work among the Cossacks, he was arrested. After another officer’s honor, he was removed from the division, demoted and sent home. Here, in the position of the head of the regimental training team, podseaul ND Kashirin and met a revolution. The same difficult path of a revolutionary was made in those years by his younger brother Ivan Kashirin: a court of honor, expulsion from a division, a struggle against ataman A.I. Dutov in his native village. But despite the hyperactivity of some restless Carbonaria, as historian I.V. Nar “enlightened society obviously exaggerated the disasters of the population, autocratic oppression and the degree of secret introduction of the state into the lives of subjects ...”. As a result, "the level of politicization of the population remained quite low."

But everything changed the war. The first changes in the moods of the Cossack society were caused by failures in the Russian-Japanese war. After the signing of the Portsmouth Peace, in order to pacify the rebellious Russia, the Cossack regiments of the second line are sent from Manchuria to the cities of Russia. The Bolsheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries already then called on the people to arms and to the brutal massacre of the "enemies of the revolution" - the Cossacks. The Moscow Committee of the RSDLP, in December 1905, sent the “Tips for the Rebel Workers” to grass-roots organizations. It read: “... do not regret the Cossacks. They have a lot of national blood, they are always enemies of the workers. ... look at them as the worst enemies and destroy them without mercy ... ". And although soldiers, sailors, gendarmes, dragoons and Cossacks were used in the pacification of the insurgent people, the Cossacks aroused the particular anger and hatred of the “shakers of state foundations”. In fact, the Cossacks were considered the main culprits for the defeat of the workers and peasants in the first Russian revolution. They were called "royal oprichniki, satrap, nagochechnikami", ridiculed in the pages of the liberal and radical press. But in fact, the revolutionary movement, led by the liberal press and the intelligentsia, sent the peoples of Russia to the path of general chaos and even greater enslavement. And the people then managed to see the light, self-organize and show a sense of self-preservation. The king himself wrote about this to his mother: “The result happened incomprehensible and ordinary with us. The people were outraged by the arrogance and audacity of revolutionaries and socialists, and since 9 / 10 are Jews, the whole anger fell on those, hence the Jewish pogroms. It is amazing how unanimously and immediately this happened in all cities of Russia and Siberia. ” The king called for the unification of the Russian people, but this did not happen. In the following decades, the people not only did not unite, but finally split into hostile political parties. In the words of Prince Zhevakhov: "... from 1905, Russia turned into a lunatic asylum, where there were no patients, but there were only crazy doctors who threw her with their insane recipes and universal remedies for imaginary diseases." However, the revolutionary propaganda among the Cossacks did not have much success and, despite some fluctuations of the Cossacks, the Cossacks remained loyal to the tsarist government, carried out his orders for the protection of public order and the suppression of revolutionary actions.

During the preparations for the elections to the I State Duma, the Cossacks expressed their demands in the mandate of the 23 points. The Duma included Cossack deputies who advocated better life and empowerment of the Cossacks. The government went to meet part of their demands. The Cossacks began to receive 100 rubles (instead of 50 rubles) for the purchase of a horse and equipment, strict restrictions on the movement of the Cossacks were lifted, absences were allowed up to 1, with the permission of the village, the order of admission to military schools was improved, officers were retired; Received in economic and business activities. All this helped to improve the welfare of families and increase the village capital.

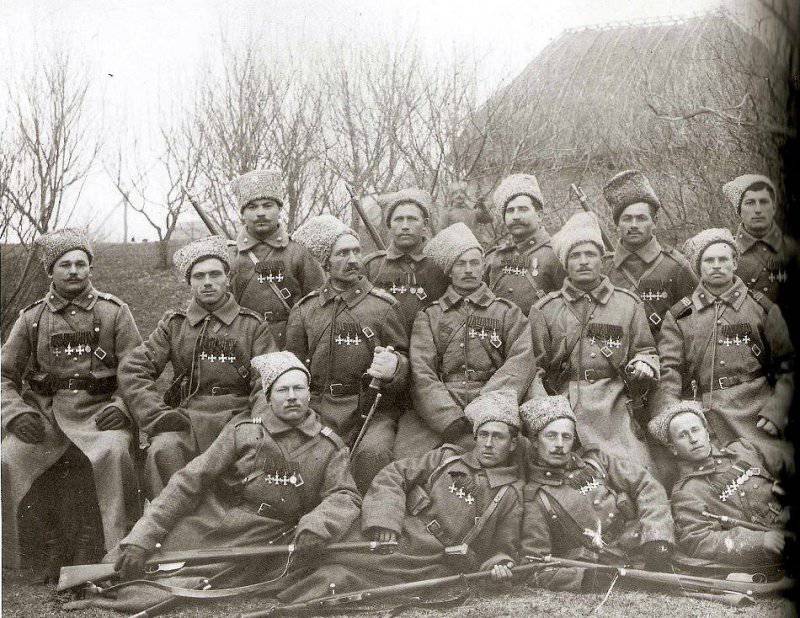

The Cossacks, like the whole of Russian society, greeted the Great War with enthusiasm. Cossacks selflessly and bravely fought on all fronts, as described in more detail in the articles Cossacks and the First World War. Part I, II, III, IV, V ". However, by the end of 1916, war fatigue swept the masses widely. People grieved about losses, about the futility of war, which has no end in sight. This created irritation against the authorities. In the army began to occur excesses, previously simply unthinkable. In October, around the Gomel distribution point, about 1916 thousands of soldiers and Cossacks rebelled on the grounds of discontent with the officers and the war. The uprising was brutally suppressed. The matter was aggravated by persistent rumors that the Empress and her entourage is the main cause of all the turmoil, that she, the German princess, is closer to Germany than to Russia, and that she sincerely rejoices in any success of German weapons. Even the tireless charitable work of the Grand Duchess and her daughters did not save from suspicion.

Figure.2 Hospital in the Winter Palace

Indeed, in the court environment of the king, in the civil and military administration there was a strong stratum of people of German origin. On 15, April 1914 was 169 Germans (48%) among 28,4 “full generals”, German 371 (73%) was among 19,7 lieutenant generals (1034%) among 196 German generals. On average, a third of the command posts in the Russian Guard were occupied by the Germans by 19. As for the Imperial Suite, the summit of state power in Russia in those years, among the 1914 adjutants-generals of the Russian Tsar of the Germans were 53 people (13%). From the 24,5 major generals and the rear admirals of the Tsar's retinue the Germans were 68 (16%). From 23,5 the German adjutants numbered 56 (8%). In total, in the "His Majesty's Suite" of 17 people the Germans were 177, that is, every fifth (37%).

Of the highest posts - corps commanders and chiefs of staff, commanders of the military districts - the Germans occupied the third part. In navy the ratio was even greater. Even the chieftains of the Tersky, Siberian, Trans-Baikal and Semirechensky Cossack troops at the beginning of the 1914th century were generals of German origin. So, on the eve of XNUMX, the Terek Cossacks were headed by the chief ataman Fleisher, the Transbaikal Cossacks - the ataman Evert, the seven-member Cossacks - ataman Folbaum. All of them were Russian generals of German descent, appointed to the Ataman posts by the Russian tsar from the Romanov-Holstein-Gottorp dynasty.

The share of the “Germans” among the civil bureaucracy of the Russian Empire was somewhat smaller, but also significant. To all of the above, it is necessary to add close, branched Russian-German dynastic ties. At the same time, the Germans in the Russian Empire accounted for less than 1,5% of the total population. It should be said that among the people of German origin there was a majority, who was proud of its origin, strictly kept in the family circle of national customs, but no less honestly served Russia, which for them was, undoubtedly, the Motherland. The hard experience of the war showed that bosses with German surnames, who held responsible posts for commanders of armies, corps and diasions, were not only professional qualities not lower than bosses with Russian surnames, but often much higher. However, in the interests of not quite respectable patriotism, the persecution of everything Germanic began. It began with the renaming of the capital of St. Petersburg to Petrograd. The commander of the 1 Army, General Rennenkampf, who showed the ability to take the initiative in difficult conditions at the beginning of the war, like the other Commander Scheidemann, who, at ód, saved the 2 Army from the secondary defeat, were removed from the command. The unhealthy psychology of leavened patriotism, which rose to the very top and later became the reason for accusing the reigning family of national treason, coexisted.

Since the fall of 1915, Nicholas II, after leaving for GHQ, has already taken much less part in running the country, but the role of his wife, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, has grown dramatically, which is extremely unpopular because of her character and German origin. Power, in essence, was in the hands of the empress, the tsarist ministers and the chairman of the State Duma.

Tsarist ministers, due to numerous mistakes, miscalculations and scandals, quickly lost credibility. They were ruthlessly criticized, called "on the carpet" in the Duma and the Stavka, constantly changed. During 2,5, the years of war in Russia were replaced by 4 Chairman of the Council of Ministers, 6 Ministers of the Interior, 4 Minister of War, 4 Minister of Justice and Agriculture, which was called the “ministerial leapfrog”. Of particular irritation of the liberal Duma opposition was the appointment of an ethnic German B. V. Sturmer as prime minister during the war with Germany,

The State Duma of the fourth convocation that was in effect at that time actually became the main center of opposition to the tsarist government. The moderate liberal majority of the Duma united in the 1915 year in the Progressive Bloc, which openly opposed the tsar. The cadet parties (leader P.N. Milyukov) and the Octobrists became the core of the parliamentary coalition. Beyond the bloc there were left both the right-wing monarchist deputies who defended the idea of autocracy, and sharply opposition left radicals (Mensheviks and Trudoviks). The Bolshevik faction in November 1914 of the year was arrested as having not supported the war. The main slogan and demand of the Duma was the introduction in Russia of a responsible ministry, that is, a government appointed by the Duma and responsible to the Duma. In practice, this meant the transformation of the state system from autocracy into a constitutional monarchy along the lines of Great Britain.

Another important opposition squad was Russian industrialists. Large strategic miscalculations in military construction before the war led to an acute shortage of weapons and ammunition in the army. This required a massive transfer of Russian industry to the war footing. Against the background of the helplessness of the regime, various public committees and unions began to arise everywhere, taking on their shoulders the daily work that the state could not properly do: caring for the wounded and injured, supplying cities and the front. In 1915, major Russian industrialists began to form military-industrial committees - independent public organizations in support of the empire's military efforts. These organizations, led by the Central Military-Industrial Committee (TsVPK) and the Main Committee of the All-Russian Zemsky and Urban Unions (Zemgor), not only solved the problem of supplying the front with weapons and ammunition, but also turned into a mouthpiece of the opposition close to the State Duma. Already the II Congress of the MIC (25-29 July 1915) gave the slogan of the responsible ministry. The famous merchant P. P. Ryabushinsky was elected chairman of the Moscow military industrial complex. A number of future leaders of the Provisional Government emerged from the MIC. The leader of the Octobrists, A.I. Guchkov, was elected chairman of the Central Military Industrial Complex in 1915, Prince G.Ye. Lvov was elected chairman of Zemgor. The relations of the tsarist government with the movement of the military-industrial complex were very cool. A special irritation was caused by the Working Group of the Central Military Committee, which was close to the Mensheviks, which actually formed the core of the Petrograd Soviet during the February Revolution.

Starting in the autumn of 1916, not only left radicals, industrialists and the liberal State Duma, but even the closest relatives of the tsar himself — great princes, who at the time of the revolution numbered 15 people, rose into opposition to Nicholas II. Their demarches went down in history as the "Grand-Ducal Frond." The general requirement of the great princes was the removal of Rasputin and the German queen from government and the introduction of a responsible ministry. Even his own mother, the widowed empress Maria Feodorovna, rose up in opposition to the tsar. October 28 in Kiev, she directly demanded the resignation of Sturmer. The Fronda, however, was easily suppressed by the king, who by 22 in January 1917 had sent the great princes Nikolai Mikhailovich, Dmitry Pavlovich, Andrei and Kirill Vladimirovich from the capital city under various pretexts. Thus, the four great princes found themselves in royal opal.

All these increased state forces gradually approached the highest military command, having imperial power among themselves and creating the conditions of its full absorption day with a weak emperor. So, little by little, there was preparation for the great drama of Russia — the revolution.

The history of Rasputin's malignant influence on the Empress and her entourage undermined the reputation of the royal family. From the point of view of defective morals and cynicism, the public did not stop even before accusing the empress of intimate relations with Rasputin, and in foreign policy in connection with the German government, to whom she allegedly radioed secret information from Tsarskoe Selo .

November 1 1916, the leader of the cadet party, P.N. Milyukov made his “historical speech” in the State Duma, in which he accused Rasputin and Vyrubova (the Empress maid of honor) of treason in favor of the enemy, which happens before our eyes, which means with the knowledge of the empress. Purishkevich spoke next with an evil speech. Speeches in hundreds of thousands of copies spread throughout Russia. As Grandfather Freud used to say in such cases: “The people believe only in what they want to believe in.” The people wanted to believe in the treason of the German Queen and received "evidence." Whether this was true or false was the tenth case. As is well known, after the February Revolution, the Emergency Commission of the Provisional Government was created, which from March to October 1917 carefully searched for evidence of “treason”, as well as corruption in the tsarist government. Hundreds of people were questioned. Nothing was found. The commission concluded that there could be no talk of any treason against Russia on the part of the empress. But as Freud said: “The wilds of consciousness are a dark matter.” And there was no ministry, department, office or headquarters in the country in the rear and at the front, in which these speeches scattered throughout the country in millions of copies were not copied and reproduced. Public opinion recognized the mood that was created in the State Duma 1 on November 1916 of the year. And this can be considered the beginning of a revolution. In December 1916, a meeting of the Zemsky City Union (Zemgora), chaired by Prince G.Ye.Lovov, was held at the Hotel France in Petrograd on the subject of saving the Motherland through a palace coup. It discussed questions about the expulsion of the tsar and his family abroad, about the future state system of Russia, about the composition of the new government and about the wedding of Nicholas III, the former Supreme Commander. Member of the State Duma, the leader of the Octobrists A.I. Guchkov, using his connections among the military, gradually began to involve prominent military leaders in the conspiracy: War Minister Polivanov, chief of staff of the General Headquarters General Alekseev, generals Ruzsky, Krymov, Teplov, Gurko. In the history of mankind there were no (no, and never will be) revolutions in which truth, half-truth, fiction, fantasy, falsehood, lies and slander would not be densely mixed. No exception and the Russian revolution. Moreover, the Russian liberal intelligentsia joined in the business here, who for centuries lived and lives in the world of manilovism and social “fantasy”, heavily mixed with traditional intellectual tricks: “disbelief and doubt, blasphemy and snede, ridicule of customs and morals ...” and etc. And who will distinguish in the murky waters of the pre-revolutionary bedlam of fantasy and fabrication from slander and lies. Slander has done its job. In just a few months 1916, under the influence of slanderous propaganda, the people lost all respect for the empress.

The situation with the authority of the emperor was no better. He was represented as a person engaged exclusively in questions of the intimate aspect of life, who resorted to stimulating media supplied by the same Rasputin. It is characteristic that the attackers, who were headed for the honor of the imperialist, came not only from the highest command layer and advanced society, but also from the numerous imperial surnames and closest relatives of the king. The personality of the sovereign, the prestige of the dynasty and the imperial house served as objects of unchecked lie and provocation. By the beginning of 1917, the morale state of Russian society was a pronounced sign of pathological conditions, neurasthenia and psychosis. The idea of changing the state government was infected by all segments of the political community, most of the ruling elite and the most visible and authoritative persons of the dynasty.

Having assumed the title of Supreme Commander, the emperor did not show the talents of the commander, and, having no character, he lost the last authority. General Brusilov wrote about him: “It was well known that Nicholas II in the military did not understand anything ..., by the nature of his character, the king was more inclined to positions hesitant and indefinite. He never liked to dot the i ... Neither a figure nor the ability to speak, the king did not touch the soldier’s soul and did not make the impression necessary to lift the spirit and attract the hearts of soldiers to him. The king’s contact with the front consisted only in the fact that he received a summary of information about the incidents at the front every evening. This relationship was too small and clearly indicated that the king was not interested in the front and in no way takes part in the execution of the complex duties entrusted by law to the Supreme Commander. In reality, the king at Bid was bored. Every day at 11 in the morning he received a report from the Chief of Staff and the Quartermaster General on the situation at the front, and that was the end of his command and control. The rest of the time he had nothing to do, and he tried to drive around to the front, now to Tsarskoye Selo, then to different places in Russia. Accepting the posts of Supreme Commander was the last blow that Nikolay II dealt himself with and which resulted in the sad end of his monarchy. ”

In December, the most important meeting of the senior military and economic leadership for planning the 1916 campaign was held at GHQ in Stavka. The emperor remembered on him that he did not participate in the discussions, constantly yawned, and the next day, having received news of the murder of Rasputin, he left the meeting altogether before it ended and went to Tsarskoye Selo, where he stayed until February. The authority of the tsarist government in the army and the people was finally undermined and fell, as they say, below the plinth. As a result, the Russian people and the army, including the Cossacks, did not stand up for not only their Sovereign, but also their own state, when in February days in Petrograd a revolt against the autocracy broke out.

22 February, despite the difficult condition of his son Alexei, his daughter's illness and political ferment in the capital, Nicholas II decided to leave Tsarskoye Selo to Headquarters to keep the army from anarchy and defeatism by its presence. His departure served as a signal to activate all the enemies of the throne. On the next day, February 23 (March 8 in a new style), a revolutionary explosion occurred that marked the beginning of the February revolution. Petrograd revolutionaries of all stripes used the traditionally celebrated International Women's Day to hold rallies, meetings and demonstrations to protest against the war, high prices, lack of bread and the general plight of workers in factories. With bread in Petrograd there were indeed interruptions. Due to snow drifts, there was a big traffic jam on railway roads, and 150 LLC carriages were stationary without traffic. In Siberia and on the other outskirts of the country there were large food warehouses, but in the cities and the army there was a shortage of food products.

Fig. 3 Bread Queue in Petrograd

From the workers' outskirts, the column of workers excited by the revolutionary speeches headed to the city center, and a powerful revolutionary stream formed on Nevsky Prospect. On that tragic day for Russia, 128 of thousands of workers and laborers went on strike. The first clashes with the Cossacks and the police took place in the center of the city (the 1, 4, 14, Don Cossack regiments, Guards Cossack Regiment, 9 reserve cavalry regiment, Kexholm reserve battalion participated). However, the reliability of the Cossacks themselves was already in question. The first case of the refusal of the Cossacks to shoot into the crowd was noted as early as May 1916 of the year, and in total there were nine such cases in 1916 year. The 1 th Don Cossack regiment during the dispersal of the demonstrators showed a strange passivity, which the regiment commander Colonel Troilin explained by the absence of a regiment in the gag. By order of General Khabalov, the regiment allocated 50 kopecks for a Cossack to get their whips. But Rodzianko, the chairman of the State Duma, categorically forbade the use of weapons against protesters, so the military command was paralyzed. The next day, the number of strikers reached an unprecedented size - 214 thousand people. There were continuous mass rallies on Znamenskaya Square, here the Cossacks refused to disperse the demonstrators. There were other cases of disloyal behavior of the Cossacks. During one of the incidents, the Cossacks drove out the policeman who hit the woman. By evening, the looting and pogroms of shops began. February 25 began a general political strike that paralyzed the economic life of the capital. The guard Krylov was killed on Znamenskaya Square. He tried to force his way through the crowd to break the red flag, but the Cossack struck him with several blows with a saber, and the demonstrators finished off the police officer with a shovel. The departure of the 1 Don Cossack Regiment refused to shoot the workers and fled the police squad. At the same time propaganda was carried out among the spare parts. A mob opened a prison and criminals were released, which gave the most reliable support for revolution leaders. Police pogroms began, the District Court building was set on fire. In the evening of this day, the king, by his decree, dissolved the State Duma. The Duma members agreed, but did not leave, but began an even more vigorous revolutionary activity.

The Tsar also ordered the commander of the Petrograd Military District, Lieutenant General Khabalov, to immediately stop the unrest. Additional military units were introduced to the capital. 26 February in several areas of the city there were bloody clashes of the army and police with demonstrators. The most bloody incident took place on Znamenskaya Square, where a company of the Volynsky Life Guards regiment opened fire on demonstrators (only here were 40 killed and 40 injured). Mass arrests were made in public organizations and political parties. The opposition leaders who survived the arrests appealed to the soldiers and called on the soldiers to unite with the workers and peasants. Already in the evening, the 4 uprising company of the reserve (training) battalion of the Pavlovsky Guards regiment raised. The army began to side with the rebels. And on February 27, a general political strike developed into an armed uprising of workers, soldiers and sailors. The first were the soldiers of the training team of the Volynsky Life Guards Regiment. In response to an order from the head of the training team, Captain Lashkevich, to patrol the streets of Petrograd to restore order, the non-commissioned officer of the regiment, Timofey Kirpichnikov, shot him. This murder served as a signal to the beginning of a fierce massacre of soldiers over officers. The new commander of the Petrograd Military District L.G. Kornilov regarded Kirpichnikov's deed as an outstanding feat in the name of the revolution and awarded him the Cross of St. George.

Fig.4 First soldier of the revolution Timofey Kirpichnikov

Fig.4 First soldier of the revolution Timofey KirpichnikovBy the end of February 27, about 67 thousands of soldiers of the Petrograd garrison had gone over to the side of the revolution. In the evening, the first meeting of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers 'and Soldiers' Deputies was held in the Tauride Palace. The Council began to create a working militia (militia) and the formation of district authorities. From this day began a new era in the history of Russia - Soviet power. On February 28, the empress sent two telegrams to the sovereign, informing him of the hopelessness of the situation and the need for concessions. March 1 Petrograd Soviet issued Order No. 1, which provided for measures to democratize the troops of the Petrograd garrison, and the transition to elections without prior arrangement of company, regimental, divisional and army committees. On this democratic wave, excesses also began in army units, insubordination to orders and expulsion of objectionable officers from units. Subsequently, such an uncontrollable democratization allowed the enemies of Russia to finally decompose and destroy not only the Petrograd garrison, but the entire army, and then expose the front. The Cossack army was a powerful and well-organized military mechanism. Therefore, in spite of order No. XXUMX of the Petrosoviet, which provoked mass non-execution of orders and desertion in the army, military discipline in the Cossack units was maintained at the same level for quite a long time.

Prime Minister Prince Golitsyn refused to perform his duties, leaving the country without a government, and the streets were dominated by crowds and masses of disbanded soldiers of reserve battalions. The emperor was presented with a picture of universal rebellion and discontent with his rule. Eyewitnesses painted Petrograd, demonstrations on its streets, slogans “Down with war!”, Explained that the country became uncontrollable and anarchy can be stopped only if the sovereign renounces the throne. The sovereign was at GHQ.

Tsar Nicholas II, while in Mogilev, was following the events in Petrograd, although, to tell the truth, it was not quite adequate to the impending events. Judging by his diaries, the entries for these days are basically such: “I drank tea, read, walked, slept for a long time, played dominoes ...”. One can rightly say that the emperor slept in a revolution in Mogilev. Only on February 27 the emperor became worried and by his decree he again dismissed the commander of the Petrograd military district and appointed to the post an experienced and dedicated General Ivanov. At the same time, he announced his immediate departure to Tsarskoye Selo, and for this he was ordered to prepare the lettered trains. By this time, in order to carry out revolutionary goals, the Provisional Committee of the State Duma was formed in Petrograd, which was joined by a union of railway workers, most of the higher command personnel and the highest part of the nobility, including representatives of the dynasty. The Committee removed the royal Council of Ministers from government. The revolution developed and won. General Ivanov acted hesitantly, and he had no one to lean on. The numerous Petrograd garrison, consisting mainly of reserve and training teams, was extremely unreliable. Even less reliable was the Baltic Fleet. Before the war in naval construction gross strategic mistakes were made. That is why in the end it turned out that the extremely expensive Baltic Fleet linear fleet practically all of World War I stood in Kronstadt against the “wall”, accumulating the revolutionary potential of sailors. Meanwhile, in the north, in the Barents Sea basin, since there was not a single significant warship there, it was necessary to re-create a flotilla, buying back old trophy Russian battleships from Japan. In addition, there were constant rumors about the transfer of part of the sailors and officers of the Baltic Fleet for the formation of crews of armored trains and armored units with subsequent dispatch to the front. These rumors excited the crews and stirred up protest moods.

General Ivanov, being near Tsarskoye Selo, maintained contact with the Headquarters and waited for the arrival of reliable units from the front line. The leaders of the conspiracy, Prince Lvov and the Chairman of the State Duma Rodzianko, did everything to prevent the tsar from returning to Petrograd, knowing full well that his arrival could radically change the situation. The Tsarsky train, due to the sabotage of the railroad workers and the Duma, could not get to Tsarskoe Selo and, changing the route, arrived in Pskov, where the headquarters of the Northern Front commander, General Ruzsky, was located. Upon arrival in Pskov, the sovereign's train was not met by anyone from headquarters, after some time Ruza appeared on the platform. He passed into the carriage of the emperor, where he remained for a short time, and, going into the carriage of the retinue, declared the hopeless situation and the impossibility of suppressing the rebellion by force. In his opinion, one thing remains: to surrender to the mercy of the winners. Ruzsky spoke on the phone with Rodzianko, and they came to the conclusion that there was only one way out of the situation - the sovereign's abdication. On the night of March 1, General Alekseev sent a telegram to General Ivanov and all the commanders of the fronts with orders to stop the movement of troops to Petrograd, after which all the troops assigned to suppress the insurrection were returned.

March 1 of the authoritative members of the Duma and the Provisional Committee was formed by the Provisional Government headed by Prince Lvov, the outlines of which were outlined in December in the fashionable room of the hotel "France". Representatives of big capital (capitalist ministers) also became members of the government; the socialist Kerensky took the post of minister of justice. At the same time, he was a companion (deputy) to the chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, formed two days earlier. The new government, through the chairman of the State Duma Rodzianko, telegraphed to the king a demand for abdication. At the same time, the Chief of Staff of the Supreme Command, General Alekseev, organized a telegraph survey on the same topic of all the commanders of the fronts and fleets. All the commanders, with the exception of the Black Sea Fleet commander Admiral Kolchak, repulsed telegrams about the desirability of the tsar’s abdication in favor of the heir’s son. Considering the incurable disease of the heir and the rejection of the regency of the Great Princes Mikhail Alexandrovich and Nikolai Nikolayevich, these telegrams meant a sentence to the autocracy and the dynasty. Special pressure on the king had generals Ruzsky and Alekseev. Of all the generals, only the commander of the 3 Cossack Cavalry Corps, Count Keller, expressed his willingness to move the corps to the defense of the king and reported this to the Headquarters with a telegram, but he was immediately removed from his post.

Members of the Duma Shulgin and Guchkov came to Ruza’s headquarters, demanding renunciation. Under pressure from others, the sovereign signed the act of renunciation for himself and for the heir. This happened on the night of March 2 1917. Thus, the preparation and execution of the plan for overthrowing the supreme power required a complex and lengthy multi-year preparation, but it took only a few days to complete this task, not more than a week.

The power was transferred to the Provisional Government, which was formed mainly from members of the State Duma. For the army, as well as for the province, the sovereign's abdication was "thunder in a clear sky." But the manifesto of the renunciation and the oath decree to the Provisional Government showed the legality of the transfer of power from the sovereign to the newly formed government, and demanded obedience. Everything that happened was calmly accepted by the army, the people, and the intelligentsia, who so long ago and so persistently promised a new, better structure of society. It was assumed that people who knew how to arrange the latter came to power. However, it soon became apparent that the new rulers of the country were not state people, but minor adventurers who were completely unsuitable not only to manage a vast country, but were not even able to ensure quiet work in the Tauride Palace, which turned out to be filled with the influx of mob. Russia entered the path of lawlessness and anarchy. The revolution brought to the power of people completely worthless, and very quickly it became very clear. Unfortunately, in the course of the Smoot, people are almost always put on the public arena who are not very suitable for effective activity and who are not able to manifest themselves in personal work. It is this part that rushes, as usual, in the hard time towards politics. There are not many examples when a good doctor, engineer, architect, or talented people from other professions will give up their activities and prefer to engage in political affairs.

The Cossacks, like the rest of the people, also calmly, even indifferently, met the emperor's abdication. In addition to the above reasons, the Cossacks had their own reasons to treat the emperor without due piety. Before the war, the Stolypin reforms were carried out in the country. They actually eliminated the privileged economic situation of the Cossacks, without at all weakening their military duties, which many times exceeded the military duties of the peasants and other classes. This, as well as military failures and stupid use of Cossack cavalry in the war, gave rise to Cossacks indifference to the royal power, which had great negative consequences not only for the autocracy, but also for the state. This indifference of the Cossacks allowed the anti-Russian and anti-popular forces, with impunity, to overthrow the Tsar first, and then the Provisional Government, having liquidated the Russian state. Not immediately, the Cossacks understood what was happening. This gave the anti-Russian government of the Bolsheviks a break and an opportunity to gain a foothold in power, and then gave the opportunity to win the civil war. But it was in the Cossack regions that the Bolsheviks met the strongest and most organized resistance.

Already soon after the February Revolution, polarization and disengagement of political forces took place in the country. The extreme left, led by Lenin and Trotsky, sought to bring the bourgeois-democratic revolution to the socialist track and establish the dictatorship of the proletariat. The right-wing forces wanted to establish a military dictatorship and bring order to the country with an iron hand. The main contender for the role of dictator was General L.G. Kornilov, but he turned out to be completely unsuitable for this role. The most numerous middle of the political spectrum was simply a great gathering of irresponsible talkers-intellectuals who were generally unsuitable for any effective action. But that's another story.

Materials used:

Gordeev A.A. - History of the Cossacks

Mamonov V.F. and others. - History of the Cossacks of the Urals. Orenburg-Chelyabinsk 1992

Shibanov N.S. - Orenburg Cossacks of the XX century

Ryzhkova N.V. - Don Cossacks in the wars of the early twentieth century-2008

Unknown tragedies of the First World War. Captives. Deserters. The refugees M., Veche, 2011

Oskin M.V. - The collapse of the horse blitzkrieg. Cavalry in the First World War. M., Yauza, 2009.

Brusilov A.A. My memories. Military Publishing. M.1983

Information