Triumphal escape

As two German cruisers - “Goben” and “Breslau” - predetermined the course of the Great War

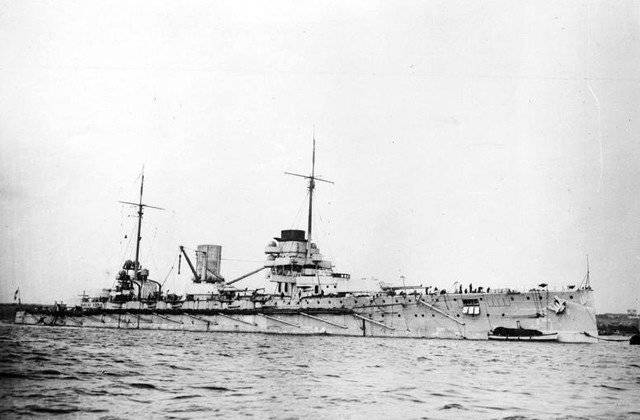

The beginning of the Great War was the "high point" for the Kaiserliche Marine - the Imperial Naval fleet Germany. In just a few days of August 1914, with the help of only two cruisers - the linear Geben and the light Breslau - the Germans managed to smash the myth of the vaunted power and training of the British fleet, then considered the universally recognized Queen of the Seas. Under the command of Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, the crews of these warships were able to do almost incredible - break through the entire Mediterranean Sea to Constantinople, while being surrounded by many times superior forces of several British and French squadrons. The naval version of the exciting game of "cat and mouse" ended for the sons of Misty Albion with an unconditional defeat.

Moreover, if for the British fleet it remained only a problem of prestige, then for the Russian Empire the brilliant escape of the German squadron became a kind of “moment of truth”. German ships, especially the modern powerful “Goeben”, sharply increased the combat potential of the Turkish military fleet. As a result, already 27 September 1914, Turkey closed the Dardanelles Strait to merchant ships of all countries. For Russia, this became a real catastrophe due to the acute shortage of the main ammunition (cartridges, shells, rifles), as well as other military equipment. To reduce the severity of this deficit could only military supplies of the Allies on the Entente, which now became impossible through the Dardanelles - the “gateway” to the Black Sea.

Squadron of two ships

In the official naval stories it is believed that the battle cruiser “Goeben” and the light cruiser “Breslau” were the Mediterranean squadron of the German Navy and had the task, in the event of the outbreak of war between Germany and France, to prevent the transfer of the French expeditionary force from Algeria to Europe. This version does not take into account at least two important circumstances.

The first. At the time of the beginning of the Great War, there was a special agreement between the United Kingdom and the French Republic that passed into the area of responsibility of the British Navy to ensure the shipping of allies in the English Channel and the protection of the northern coast of France. This agreement allowed the French to concentrate their entire fleet in the Mediterranean, with the total tonnage of only the linear French fleet (battleships, linear and armored cruisers) exceeding the total tonnage of the Geben and Breslau more than 8 times. Given the light cruisers and destroyers of the destroyers, the superiority of the French Navy over the so-called Mediterranean squadron of the German Navy became generally overwhelming.

The second. On the island of Malta, located between the southern coast of Europe and North Africa, was based the British Mediterranean Fleet. The artillery power of the British ships would easily have been enough for several Gebens, since this fleet had three newest battle cruisers (of the Inflexible type), and in addition, four armored cruisers (Defense, Black Prince, Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh), four light cruisers and a flotilla of 14 destroyers.

Thus, the two German cruisers initially did not have the slightest opportunity not to interrupt, but even effectively prevent the transfer of French troops from Algeria to mainland France. It is also very difficult to consider “Geben” and “Breslau” a squadron, since cover ships (at least a few destroyers) must be included in the full-fledged squadron. So, in reality, they could only have the task of demonstrating the naval flag of Kaiser Germany in the Mediterranean basin. Under the conditions of war, for some time German cruisers could perform the function of raiders. With both of these tasks they successfully coped.

From the dock - to breakthrough!

The beginning of World War I - 28 July 1914, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia - was hit by the battle cruiser “Goeben” at the wall of the ship repair dock in the Austrian port of Pola (now Pula in Croatia - RP), located on the Adriatic coast. The commander of the German formation of ships, Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, without receiving any intelligible instructions from the Naval Headquarters of Germany, immediately brought his ships out of the "bag" of the Adriatic to the expanses of the Mediterranean Sea. The admiral truly understood that the time was running not even for days, but for hours.

“Goeben” left the raid. Floors are practically in a semi-emergency condition: the unrepaired boilers became the main problem of the ship. With a constructive speed in 27 nodes, the battlecruiser could hardly issue near the 24 node. However, even this speed was maintained with difficulty - exclusively by the professional, even heroic work of the specialists of the engine room (during the 14 days of the “Geben” raid, four stokers died at the boiler’s furnaces, burned to death by the suddenly bursting steam).

Despite the poor technical condition of the cruiser, Wilhelm Souchon decided to say goodbye to "loudly slam the door." From Paula, the German ships went in the direction of Algeria - to bombard the French Algerian ports of Bon and Philipville (now Skikda).

Already on the way to Algeria on August 3 1914, the German admiral received a radiogram on 18.00 that Germany declared war on France. In the morning of August 4 came the order of the German Navy Commander, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who set the course for the German raiders to Constantinople. Having received this order, Wilhelm Souchon did not change, nevertheless, his original decision and delivered an artillery strike on Philipville and Bon.

Having shot the French ports, the German raiders, having raised the pressure in the boilers, defiantly turned along the Algerian coast to the west - with the exact calculation that the direction of their withdrawal would not remain unnoticed by the French civilian ships and military observers on the coast.

Indeed, the commander-in-chief of the French naval forces, Admiral Augustin de Lapeirer, was immediately reported on the radio that the Germans had gone to the west - towards Gibraltar. Based on this information, the French admiral sent three strong squadrons from Toulon to intercept the German cruisers. The squadrons moved like a fan - one for Bon, the second for Philipville and the third for Oran, hoping to catch the bold Teutons in a maximum of 2 and a half hours. Alas, after leaving Toulon, the French cruisers began to catch the air - German raiders, turning out of sight from the coast, at that time were already rushing in the opposite direction, northeast, in the direction of Italian Messina (port in northeast Sicily - RP) .

The silence of the English captains

In 9 hours 32 minutes 4 August 1914, Admiral Wilhelm Souchon saw powerful fumes of large warships on a cross course. On the German raiders immediately struck alarm.

The smoke belonged to the newest British battle cruisers Inflexible and Indomiteble, as well as to the light cruiser Dublin. Having approached the German ships to 43 cable (8000 meters), the British lay on a parallel course. It is very curious that the British guns were set in a “hiking” position, and their French allies, who were very close to catching air at sea, did not receive the slightest indication of the actual presence of enemy ships.

Without small hours 6 English and German cruisers went a parallel course to the east. At 15.00, Admiral Souchon gave the order to maximize the steam pressure in the boilers, and at 16.50 the silhouettes of the British “sea wolves” finally melted away on the horizon.

Why didn't the British attack? The official version says that the commanders of the British ships were ordered not to open fire before the expiration of the ultimatum, which the United Kingdom sent to Kaiser Wilhelm II. The ultimatum expired at midnight on August 5, which means the British sailors were guided by the principles of military ethics? But then what prevented them from sending French squadrons to the German raiders?

The captains of Inflexible and Indomiteble may not have the authority and instructions for such an action. However, it is quite obvious that this, logically, was to be done by the British naval command, in particular, by the commander of the British Mediterranean fleet, Admiral Archibald Milne.

The patriotism of the German merchant seamen

On 4 in the morning of 5 in August 1914, the “Goeben” and “Breslau” entered the harbor of Italian Messina. According to international maritime law, ships of a belligerent country could be located in the port of a neutral state no more than 24 hours. Knowing this, the port authorities of Messina in every way delayed the supply of coal to the German cruisers.

At this extremely dangerous hour, Admiral Souchon received confirmation that the expression “German feeling” is not empty words: teams of German merchant ships stationed in the port of Messina came to the rescue. Four hundred volunteers - simple German sailors - round-the-clock, almost by hand, loaded the coal of their ships into the Geben and Breslau bunkers. By the morning of August 6, 1500 tons of coal had been loaded, which was not enough for a breakthrough to Constantinople, but at least allowed to continue the cat-and-mouse game with the British.

The courageous German admiral, fulfilling the categorical demand of the Italian authorities, again set sail. Wilhelm Sushon's position was unenviable. The new telegram of Admiral Tirpitz left no doubt that the Austro-Hungarian allies could not count on the help of the fleet. In addition, Tirpitz reported that Turkey continues to maintain neutrality, which means that it is highly likely that Sushon’s ships will be interned in Constantinople. However, the commander of the German raiders decided not to change the course once again.

“I realized that the highest German command,” Wilhelm Souchon later wrote in his memoirs, “is in some confusion in that stream of extremely disturbing information that hit Berlin in the first days of the war. Therefore, I decided, regardless of anything, to continue to follow to Constantinople. The might of the Goeben’s cannons could have forced the Ottoman Empire, even against its will, to begin military operations in the Black Sea against its original enemy, Russia. ”

The strategic assessment of Admiral Souchon turned out to be extremely accurate: in a major military-political game, which Berlin led in Constantinople, the trump card (by the look of the German naval standard) Geben's trump card was able to beat any stakes.

Throwing admiral milne

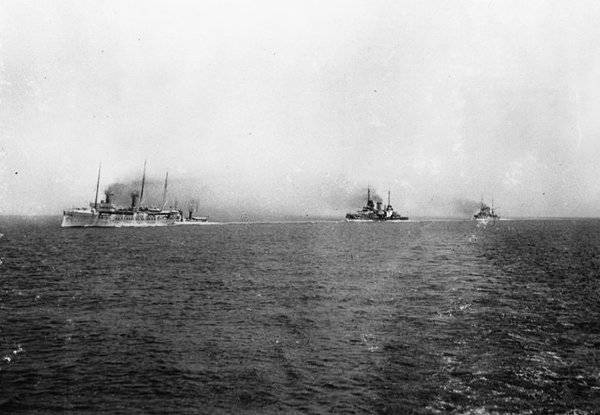

German cruisers left Messina on August 6 in 17.00. An hour later, the Germans discovered the English light cruiser Gloucester, which was on duty at the southern exit of the Strait of Messina.

It is important to emphasize that as early as the middle of the day 5 August, the Commander of the Mediterranean Fleet of Great Britain, Archibald Milne, knew that German cruisers were in the port of Messina. What prevented Milna from separating the considerable forces at his disposal and blocking the southern and northern exits from the narrow Gulf of Messina?

Famous military historian D.V. Likharev believes that the apparent clumsiness of Admiral Milne’s operational thought stemmed from the conviction that “the German ships have only two possible ways: either to break through the Atlantic via Gibraltar, or to the Austrian port of Paul through the Adriatic Sea.” D.V. Likharev also notes that the disposition of the main forces of the British Mediterranean Fleet fully corresponded to these ideas, especially given the fact that Milne received the strictest order of the English Admiralty not to approach the shores of Italy for more than 6 miles.

These arguments are undoubtedly weighty, but they do not remove the question: what prevented Milne from being on the traverse of the southern and northern entrance to the Strait of Messina more seamy, say, 8 miles away? Optical instruments of that time allowed to establish reliable visual contact with the ships of the enemy in the daytime at a distance of 24 nautical miles.

Today, it is quite difficult to guess about the real motives of the actions of Admiral Archibald Milne. In the military-historical literature there are indications that the experience of commanding large units of ships of this admiral was extremely insignificant. The most experienced "sea wolf", Admiral John A. Fisher, who held the post of First Sea Lord (Chief of the Naval Staff) in 1914-1915, considered Admiral Milne completely incapable of making responsible, independent decisions.

Whatever it was, but the commander of the British Mediterranean fleet made a strategic mistake: he placed his high-speed battlecruisers significantly west of the Strait of Messina - near the island of Pantelleria, halfway between Sicily and Tunisia. From this operational area, catching the William Sushon raiders was unrealistic. In order to prevent the German ships from traveling to Constantinople, Archibald Milne had, in essence, only one barrier - the connection of the ships of Admiral Ernest Trubridge. His squadron patrolled the exit from the Adriatic Sea and was more than enough tonnage and artillery to carry out the mission of the interceptor of German cruisers.

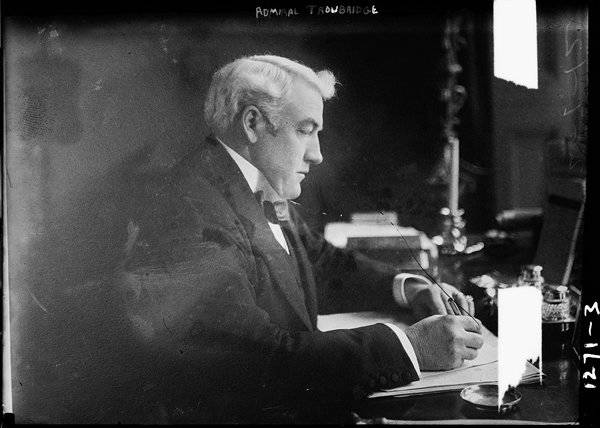

Admiral Trubridge's clever cowardice

Ernest Trubridge's squadron consisted of 12 ships: four armored cruisers - Defense (flagship), Black Prince, Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh, and eight destroyers.

According to an eyewitness to the events, the commander of the destroyer Scorpion EB Cunningham, immediately after receiving a radiogram from the “Gloucester” on the withdrawal of German cruisers from the Strait of Messina, Admiral Trubridge ordered all the squadron ships to go as quickly as possible to intercept the Germans. According to the calculations of the navigators "Difens" rapprochement with the German cruisers at a distance of effective fire should have happened around 6.00 in the morning of August 7. Earlier this time it was not possible to get close to the raiders of Wilhelm Sushon: the Trubridge armored cruisers were ships of outdated projects and did not allow keeping the speed of more than 19 nodes.

There is evidence that Admiral Trubridge was tormented by doubts during the entire period of prosecution. There were good reasons for this: the newest “Goeben” had ten 280-mm guns of the main caliber, which allowed aimed fire at 24 000 yards (about 21 km). The British could oppose this with their 234-mm guns with an effective range of 16 000 yards (14 km). True, these guns they had significantly more than the "Goeben": 36 vs. 10. Additionally, Admiral Trubridge could count on 24 inches (7,5-mm) and 190 six-inch (36-mm) caliber 152 guns. In comparison with the "Goeben", the British could, of course, give out an avalanche of fire: there was only the problem of getting close to the German cruisers.

There was another reason for doubt - the thickness of the armor belt. "Goeben" had 280-mm armor belt, the thickness of the armor of British cruisers did not exceed 150 mm. However, no armor belt could not resist the explosive effect of a torpedo, successfully released from the destroyer. It was the presence of the destroyers, as well as the light cruiser “Gloucester” that could allow Admiral Trubridge to achieve the so-called disconnection of the fire of the main German raider.

In short, the attack of the British ships on the cruiser Wilhelm Souchon did not promise an easy victory, but this victory was quite achievable, have Admiral Trubridge determined to carry it out. But her English admiral was clearly lacking.

Subsequently, Admiral Trubridge will argue that he refused to fight with German cruisers, carrying out the order previously received from Admiral Milne, “not to engage in battle with superior enemy forces”. It is difficult to understand this strange argument: how can one battlecruiser and one light cruiser be considered "superior forces" in relation to four armored cruisers accompanied by a troop of destroyers?

By the morning of August 3.30 7 it became obvious that the British squadron could not attack the German cruisers in the dark. Admiral Trubridge hesitated: the ghost of the great Nelson drove him forward, but his mind - “the son of difficult mistakes” - was authoritatively advised to stop in time and not to test the aiming devices of the German commanders. In this difficult moment, as some researchers note, the flag captain, the commander of the cruiser Defens, Fawcet Ray, intervened in the situation.

“Flag-captain of the“ Difsense ”, which was considered in the fleet to be an authoritative expert artilleryman, - writes military historian D.V. Likharev, - gave the commander an entire lecture on how he thought the battle with the Goeben would take place: taking advantage of the speed, the German battleship could keep British ships in the center of circulation with a radius of 16 000 yards or even more ” .

The result of this hypothetical maneuver "Goeben", according to Foset Ray, will inevitably be a consistent execution - one after another - of all the cruisers of the English squadron.

If all logically reasonable and technically sound calculations invariably came true in the course of military actions - the wars of states and nations most likely would not exist. They would be replaced by mutual inspections of military warehouses, during which the opposing sides would always be convinced that for a future victory they lack several thousand boxes of cartridges, 300 or 500 guns, howitzers of the required caliber, etc.

In a real war, it often happens that an intangible spirit overcomes coarse flesh. From the bayonet strike of one decisive company, it is sometimes shameful that an entire regiment escapes. The division of inspired recruits rubs in the ashes of the enemy's corps. The tank, which, according to calculations, should not have felt the impact of the ephemeral 30-mm projectile of a lightly gun at all, nevertheless, it lights up and blazes like a torch. There may be a lot of surprises in the war - it’s not for nothing that all European nations in combat orders and in symbols of military orders, in one or another paraphrase, meet the eternal, proud motto - “The Impossible happens.”

The deepest military meaning of this motto was clearly inaccessible to Admiral Ernest Trubridge. After the “lecture” conversation with his flag captain, the squadron commander sent a radiogram to the fleet headquarters, in which he announced his intention to abandon the pursuit of German cruisers. The clock on the bridge showed at this moment 4.00 hours of the morning.

The response from Admiral Milne was received only on 10.00 in the morning. In principle, this radiogram would not come at all: at this moment Trubridge’s ships had already cast anchors in the bay of the southern coast of Zante Island (off the east coast of Peloponess - RP), where the lucky pursuer of Sushona came to coal bunkering. Between him and the German cruisers, there was already a distance of 67 miles.

Admiral Wilhelm Souchon replenished coal reserves off the coast of Donus Island (located in the Aegean Sea east of Greece, about 120 km from the west coast of Turkey - RP), where the German coal ship approached on August 9. In 17.00 10 August, the German squadron reached the Dardanelles and requested permission from the Turkish authorities to pass. German ships entered the strait with main pennants on the main masts. Cruiser crews really deserve this proud gesture.

Bold glance "Gloucester"

For Sir Ernest Trubridge, with his four armored cruisers, the squadron "two" of William Souchon seemed "superior enemy forces." However, the young captain of the Gloucester light cruiser, which 6 on August 1914 of the year discovered the German cruisers emerging from the Strait of Messina, did not think so. From 18.00 6 in August, the cruiser Gloucester steadily followed the departing eastward Geben and Breslau, constantly transmitting the coordinates of these ships and awaiting Trubridge’s attack.

After 10.00 7 August it became clear that no clash between Trubridge's squadron and the German ships would not take place. Around 12.00, the captain of the Gloucester received a short radiogram of the commander of the British Mediterranean fleet, Milne, who ordered the Gloucester to stop pursuing Souchon’s ships. Despite this order, the Gloucester continued to monitor the German cruisers.

In the 13.35, the Gloucester got close to the light cruiser Breslau and opened fire with the guns of the main caliber. "Breslau" responded to the fire, and "Goeben" was forced to change course in order to come to the aid of his light brotherhood. A clash with the “Goeben” for the British light cruiser under any circumstances would be guaranteed to be the last, and the brave captain of the “Gloucester” was forced to withdraw. Later, the Germans confirmed the fact of several successful hits in “Breslau”, the most dangerous of which fell on the waterline.

In the end, while abelling Cape Matapan (the extreme southern point of the Peloponnese and mainland Greece), Gloucester stopped pursuing the enemy, following the next order of Admiral Milne.

The effects of a brilliant escape

During the First World War, in the Russian General Staff, against the background of a general decadent mood, a conspiracy theory arose that the breakthrough of “Geben” and “Breslau” into the Turkish capital was supposedly crafted by the British admirals, who carried out the tacit instructions of the British Foreign Ministry. The German cruisers, supposedly, were supposed to increase the strength of the Turkish military fleet so much that the latter would become a factor in restraining the appetites of the Russian empire for the Dardanelles and Constantinople.

This version does not hold water. The breakthrough of “Gebena” and “Breslau” de facto put an end to the career careers of admirals Milne and Trubridge. “I’m just shocked,” wrote the famous English naval commander, Vice-Admiral David Beatty, in those days, “how shocked the entire navy as a whole is with the blow that hit it. Just think - the blame for the first and almost the only major failure in the outbreak of the war lies entirely in the fleet. I fear that this shameful stain will never be erased. ” This opinion was shared by all the top commanders of the English Admiralty.

As a result, the entire period of the Great War, Admiral Archibald Milne spent on the coast, received a half-reduced salary, and after the war he was immediately dismissed.

The position of Admiral Trubridge was at first worse. From 5 to 9 in November 1914, in the city of Portland, the trial of Trubridge, accused of “criminal inaction”, was held on board the battleship Bulvark. Admiral Sydney Fremantle, who spoke to the court as an official prosecutor from the royal navy, argued that the Goeben could not work effectively with the guns of the main caliber simultaneously for four purposes. This meant that Trubridge had the opportunity, at the cost of killing some of his ships, to destroy the German battle cruiser, or at least to immobilize it, and then wait for reinforcements in the form of battle cruisers Milne.

On formal grounds (the presence of an order of "superior forces"), the court eventually acquitted Admiral Trubridge. However, the command of the military units of the ships was never entrusted to him. Up until his retirement in 1919, the admiral served ashore — as naval adviser in Serbia. The geographical position of Serbia, as well as the zero naval potential of this country, was even more strongly emphasized by the fiasco of Trubridge’s service career.

The breakthrough of “Geben” and “Breslau” to Constantinople turned out to be the most serious consequences for Russia. 16 August 1914, the German cruisers were officially transferred to the Turkish Navy. "Goeben" became "Yavuz Sultan Selim", and "Breslau" received the name "Midilli". At the same time, the crews of the ships were still German, and the energetic and talented William Sushon 23 of September 1914 was appointed commander-in-chief of the naval forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Under the influence of Germany 27 September 1914, Turkey closed the Dardanelles for merchant ships of all countries, which actually meant an economic blockade for Russia (at the beginning of the 20th century, almost 60% of export products, primarily grain, were exported from Russia via the Black Sea - RP). 2 November 1914, the Ottoman Empire officially entered the Great War on the side of the Central Powers. This decision, according to the chief of staff of the German Eastern Front, General Erich von Ludendorff, allowed the Triple Alliance to fight for two years longer.

Turkey’s entry into the Great War was a terrible blow to the defense potential of the Russian Empire. The Russians received a new 1000-kilometer front in the Caucasus and finally lost hope of resuming the passage of the Entente ships through the Dardanelles.

Under the conditions of a chronic shortage of rifles, cartridges and shells in the Russian army, the “Dardanelles factor” immediately became strategic. During the years of the Great War, Russia delivered over a billion cartridges from the Allies. Of the 37 millions of shells fired by Russian artillery during the years of the Great War, two out of every three were imported from Japan, the United States, England and France.

All this colossal military equipment was brought to the front from the north through the freezing ports of Arkhangelsk and Murmansk. According to military experts, in order to reach the barrel of the Russian cannon, each “foreign” projectile, on average, made its way into 6,5 thousands of kilometers, and each cartridge into 4 thousands of kilometers. For the “Bolivar” driven economy of a relatively poor, peasant Russia, this new burden turned out to be catastrophically heavy.

Information