KNIL: Guarding the Dutch East Indies

Indonesia under the rule of the Dutch

By the beginning of the 19th century, the Dutch Ost-India was, above all, a network of military trading trading stations on the coast of the Indonesian islands, but the Dutch had hardly moved further into the latter. The situation changed during the first half of the XIX century. By the middle of the XIX century, the Netherlands, finally crushing the resistance of the local sultans and rajas, subdued to their influence the most developed islands of the Malay Archipelago, which are now part of Indonesia. In 1859, the 2 / 3 possessions in Indonesia, formerly belonging to Portugal, were also included in the Dutch East Indies. Thus, the Portuguese lost the rivalry for influence on the islands of the Malay Archipelago to the Netherlands.

In parallel with the ousting of the British and Portuguese from Indonesia, the colonial expansion into the islands continued. Naturally, the Indonesian population met with colonization with desperate and long-term resistance. To maintain order in the colony and its defense against external opponents, among which the colonial forces of European countries competing with the Netherlands for influence in the Malay Archipelago might well have been in place, it was necessary to create armed forces intended directly for operations within the territory of the Dutch East Indies. Like other European powers possessing overseas territorial possessions, the Netherlands began to form colonial troops.

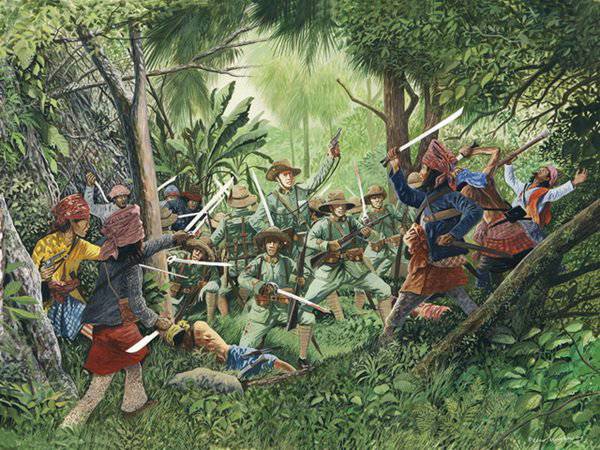

10 March 1830 was signed by the corresponding royal decree on the establishment of the Royal Dutch East Indian Army (Dutch abbreviation - KNIL). Like the colonial troops of a number of other states, the Royal Dutch East Indian Army was not part of the armed forces of the metropolis. The main tasks of KNIL were the conquest of the inner territories of the Indonesian islands, the struggle against the rebels and the maintenance of order in the colony, the protection of the colonial possessions from possible attacks by external opponents. During the XIX - XX centuries. Dutch Ost-Indies colonial troops participated in a number of campaigns in the Malay Archipelago, including the Padri wars in 1821-1845, the Javanese war 1825-1830, the crackdown on Bali in 1849, the Aceh war north of Sumatra in 1873-1904, joining Lombok and Karangsem in 1894, conquering the south-western part of Sulawesi island in 1905-1906, the final "pacification" of Bali in 1906-1908, conquering West Papua in 1920 e yy

Bali’s “enchantment” in 1906-1908, carried out by the colonial forces, was widely publicized in the world press because of the atrocities committed by the Dutch soldiers against the Balinese independence fighters. During the “Bali operation” 1906, the two kingdoms of South Bali — Badung and Tabanan — were finally subordinated, and in 1908, the Dutch East Indian Army put an end to stories The largest state on the island of Bali is the kingdom of Klungkung. By the way, one of the key reasons for the active resistance of the Balinese rajahs of the Dutch colonial expansion was the desire of the East Indies authorities to control the opium trade in the region.

Bali’s “enchantment” in 1906-1908, carried out by the colonial forces, was widely publicized in the world press because of the atrocities committed by the Dutch soldiers against the Balinese independence fighters. During the “Bali operation” 1906, the two kingdoms of South Bali — Badung and Tabanan — were finally subordinated, and in 1908, the Dutch East Indian Army put an end to stories The largest state on the island of Bali is the kingdom of Klungkung. By the way, one of the key reasons for the active resistance of the Balinese rajahs of the Dutch colonial expansion was the desire of the East Indies authorities to control the opium trade in the region. When the conquest of the Malay Archipelago could be considered a fait accompli, the use of KNIL continued, primarily in police operations against rebel groups and large gangs. Also, the tasks of the colonial troops included the suppression of the constant mass popular uprisings that broke out in different parts of the Dutch East Indies. That is, in general, they performed the same functions that were inherent in the colonial forces of other European powers, based in the African, Asian and Latin American colonies.

Recruitment of the East Indian Army

The Royal Dutch East Indian Army had its own personnel recruitment system. So, in the XIX century, the recruitment of the colonial troops was carried out primarily at the expense of the Dutch volunteers and mercenaries from other European countries, first of all - the Belgians, Swiss, Germans. It is known that French poet Arthur Rambo was recruited for service on the island of Java. When the colonial administration waged a long and difficult war against the Muslim sultanate of Aceh on the northwestern tip of Sumatra, the number of colonial troops reached 12 000 soldiers and officers recruited in Europe.

Since Aceh was considered the most religiously “fanatical” state on the territory of the Malay Archipelago, which had a long tradition of political sovereignty and was considered the “stronghold of Islam” in Indonesia, the resistance of its inhabitants was particularly strong. Realizing that the colonial troops, staffed in Europe, by virtue of their numbers cannot cope with the Aceh resistance, the colonial administration proceeded to recruit the natives. 23 was recruited by thousands of Indonesian soldiers, most notably natives of Java, Ambon and Manado. In addition, African mercenaries arrived in Indonesia from the Ivory Coast and the territory of present-day Ghana, the so-called “Dutch Guinea”, which remained under the rule of the Netherlands until 1871.

The end of the Aceh war contributed to the cessation of the practice of hiring soldiers and officers from other European countries. The Royal Dutch East Indian Army began to be completed at the expense of the inhabitants of the Netherlands, the Dutch colonists in Indonesia, the Dutch-Indonesian Métis and the Indonesians proper. Despite the fact that it was decided not to send Dutch soldiers from the metropolis to serve in the Dutch East Indies, volunteers from the Netherlands still served in the colonial troops.

In 1890, a special department was created in the Netherlands itself, whose competence included hiring and training future soldiers of the colonial army, as well as their re-rehabilitation and adaptation to a peaceful life in Dutch society after the end of the service life under the contract. As for the natives, the colonial authorities preferred when recruiting Javanese as representatives of the most civilized ethnos, in addition to everything included in the colony early on (1830 year, while many islands were finally colonized only a century later - in the 1920-s. ) and the Ambonians - as a Christianized ethnos, which is under the cultural influence of the Dutch.

In addition, African mercenaries were also recruited. The latter were recruited, first of all, among representatives of the Ashanti nationality living in the territory of modern Ghana. The inhabitants of Indonesia called the African shooters who were in the service of the Royal Dutch East Indian Army, “black Dutch”. The skin color and physical characteristics of African mercenaries terrified the local population, but the high cost of transporting soldiers from the west coast of Africa to Indonesia ultimately contributed to the gradual refusal of the colonial authorities of the Dutch East Indies from recruiting the East Indian army, including African mercenaries.

The Christian part of Indonesia, primarily the South Molluk Islands and Timor, has traditionally been considered the supplier of the most reliable contingent of troops for the Royal Dutch East Indies Army. Ambonts were the most reliable contingent. Despite the fact that the inhabitants of the Ambon Islands resisted the Dutch colonial expansion until the beginning of the 19th century, they eventually became the most reliable allies of the colonial administration among the native population. This was due to the fact that, firstly, at least half of the Ambonians adopted Christianity, and secondly, the Ambonians strongly interfered with other Indonesians and Europeans, which turned them into so-called. "Colonial" ethnicity. By participating in the suppression of the performances of the Indonesian peoples on other islands, the Ambonians deserved the full confidence of the colonial administration and, thus, secured their privileges, becoming the category of the local population closest to the Europeans. In addition to military service, Ambonians were actively engaged in business, many of them became rich and Europeanized.

The Christian part of Indonesia, primarily the South Molluk Islands and Timor, has traditionally been considered the supplier of the most reliable contingent of troops for the Royal Dutch East Indies Army. Ambonts were the most reliable contingent. Despite the fact that the inhabitants of the Ambon Islands resisted the Dutch colonial expansion until the beginning of the 19th century, they eventually became the most reliable allies of the colonial administration among the native population. This was due to the fact that, firstly, at least half of the Ambonians adopted Christianity, and secondly, the Ambonians strongly interfered with other Indonesians and Europeans, which turned them into so-called. "Colonial" ethnicity. By participating in the suppression of the performances of the Indonesian peoples on other islands, the Ambonians deserved the full confidence of the colonial administration and, thus, secured their privileges, becoming the category of the local population closest to the Europeans. In addition to military service, Ambonians were actively engaged in business, many of them became rich and Europeanized.Yavan, Sundanese, Sumatran soldiers practicing Islam received less salary compared to the representatives of the Christian peoples of Indonesia, which was supposed to encourage them to adopt Christianity, but in fact only sowed internal contradictions among the military contingent and material competition. . As for the officer corps, it was staffed almost exclusively by the Dutch, as well as by European colonists living on the island and Indo-Dutch mestizos. The number of Royal Netherlands East Indian Army at the beginning of World War II was about 1000 officers and 34 000 noncommissioned officers and soldiers. At the same time 28 000 military personnel were representatives of the indigenous peoples of Indonesia, 7 000 - the Dutch and representatives of other non-indigenous peoples.

Rising in the colonial fleet

The polyethnic composition of the colonial army repeatedly became the source of numerous problems for the Dutch administration, but she could not change the system of recruiting the armed forces deployed in the colony. European mercenaries and volunteers simply would not be enough to cover the needs of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army as a non-commissioned officer and non-commissioned officer. Therefore, it was necessary to reconcile with the service in the ranks of the Indonesian colonial troops, many of whom, for obvious reasons, were not at all loyal to the colonial authorities. The most controversial contingent was naval sailors.

As in many other countries, including the Russian Empire, the sailors were more revolutionary than the soldiers of the ground forces. This was explained by the fact that people with a higher level of education and professional training — as a rule, former workers of industrial enterprises and transport — were selected for service in the navy. As for the Dutch fleet stationed in Indonesia, Dutch workers served on the one hand, among them were followers of social democratic and communist ideas, and on the other hand representatives of a small Indonesian working class who assimilated in constant communication with their Dutch colleagues revolutionary ideas.

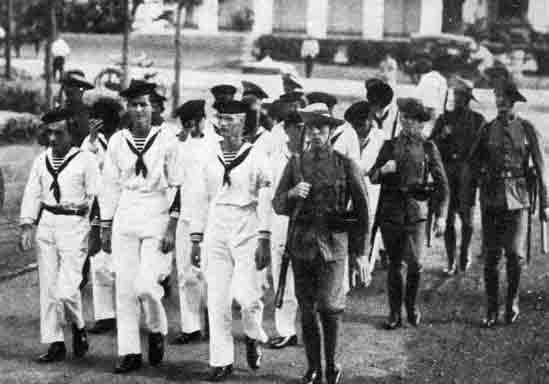

In 1917, a powerful uprising of naval sailors and soldiers broke out at the Surabaya Naval Base. The sailors were created Councils of sailor deputies. Of course, the uprising was cruelly suppressed by the colonial military administration. However, this is not the history of speeches at naval facilities in the Dutch East Indies. In 1933, a rebellion broke out on the battleship De Zeven Provintien (Seven Provinces). 30 January 1933 was a sailor’s uprising against low salaries and discrimination by Dutch officers and noncommissioned officers at the naval base of Morocrembangan, suppressed by the command. Participants in the uprising were arrested. During the exercise in the area of the island of Sumatra, the revolutionary committee of sailors created on the battleship De Zeven Provinien, decided to raise an uprising in solidarity with the sailors of the Morocrembangan. Several Dutchmen joined the Indonesian sailors, primarily those who were associated with communist and socialist organizations.

4 February 1933, when the battleship was at the base in Kotaradia, the officers of the ship went ashore to the banquet. At that moment the sailors, led by the helmsman Kavilarang and the driver Boshart, neutralized the remaining officers of the watch and noncommissioned officers and seized the ship. Battleship went to sea and headed to Surabaya. At the same time, the ship’s radio station broadcast the demands of the rebels (by the way, there were no raids): raise the sailors ’salaries, stop discrimination of the native sailors by Dutch officers and non-commissioned officers, release the arrested sailors who participated in the rebellion at the naval base of Morocrembangan (this riot occurred several days later earlier, January 30 (1933).

To suppress the uprising, a special group of ships was formed as part of the light cruiser “Java” and the destroyers “Pete Hein” and “Everest”. Commander Van Dulm, the group commander, led her to intercept the battleship De Zeven Provinien in the Sunda Islands region. At the same time, the command of the naval forces decided to transfer to the coastal units or demobilize all Indonesian sailors and staff the crew exclusively with the Dutch. 10 February 1933 The punitive group managed to overtake the rebellious battleship. The marines disembarked on deck and arrested the leaders of the uprising. Battleship was towed to the port of Surabaya. Kavilarang and Boshart, as well as other leaders of the uprising, received serious prison sentences. The uprising on the battleship "De Zeven Provinien" entered the history of the Indonesian national liberation movement and became widely known outside Indonesia: even in the Soviet Union, years later, a separate work was published on the description of the battleship of the East Indies Dutch Navy Squadron .

Before World War II

By the time World War II began, the Royal Dutch East Indian Army, stationed in the Malay Archipelago, reached 85 thousand. In addition to 1 officers and 000 soldiers and non-commissioned officers of the colonial forces, this included military and civilian personnel from the territorial guard and police units. Structurally, the Royal Dutch East Indies Army included three divisions, consisting of six infantry regiments and 34 infantry battalions; a combined brigade of three infantry battalions stationed at Barisan; a small combined brigade consisting of two battalions of the marine corps and two cavalry squadrons. In addition, the Royal Dutch East Indies Army had a howitzer division (000 mm heavy howitzers), an artillery division (16 mm field guns) and two mining and artillery divisions (105 mm mountain guns). The Mobile Squad, also armed, was created. tanks and armored cars - we will talk about it in more detail below.

The colonial authorities and military commanders took convulsive measures towards the modernization of the units of the East Indian army, hoping to turn it into a force capable of defending Dutch sovereignty in the Malayan archipelago. It was clear that in the event of a war the Royal Dutch East Indian Army was to face the Japanese imperial army, an enemy many times more serious than the rebel groups or even the colonial forces of other European powers.

The colonial authorities and military commanders took convulsive measures towards the modernization of the units of the East Indian army, hoping to turn it into a force capable of defending Dutch sovereignty in the Malayan archipelago. It was clear that in the event of a war the Royal Dutch East Indian Army was to face the Japanese imperial army, an enemy many times more serious than the rebel groups or even the colonial forces of other European powers.In the 1936 year, in an effort to protect themselves against possible aggression from Japan (the hegemonic claims of the “land of the rising sun” for the role of Southeast Asian suzerain were long known), the authorities of the Dutch East Indies decided to modernize the Royal Dutch East Indian Army. It was decided to form six mechanized brigades. The brigade should have included motorized infantry, artillery, reconnaissance units and a tank battalion.

The military command believed that the use of tanks would greatly strengthen the power of the East Indian army and make it a serious adversary. Seventy light Vickers tanks were ordered in the UK just on the eve of the start of World War II and the fighting prevented the delivery of most of the party to Indonesia. Only twenty tanks arrived. The British government confiscated the rest of the party for its own needs. Then the authorities of the Dutch East Indies turned for help to the United States. An agreement was concluded with the company Marmon-Herrington, engaged in the supply of military equipment to the Dutch East Indies.

According to this agreement, signed in 1939, it was planned to deliver a huge number of tanks to 1943 - 628 units. These were the following machines: CTLS-4 with a single tower (crew - driver and gunner); triple CTMS-1TBI and middle quadruple MTLS-1GI4. The end of 1941 was marked by the beginning of the acceptance of the first batches of tanks in the USA. However, the first ship, sent from the USA with tanks on board, ran aground when approaching the port, as a result of which most (18 of 25) machines were damaged and only 7 machines were usable without repair procedures.

The creation of tank units required the Royal Dutch East India Army and the availability of trained military personnel who were capable of serving in tank units by their professional qualities. By 1941, when the Dutch East Indies received the first tanks, the East Indian Army was trained on the armored profile of 30 officers and 500 noncommissioned officers and soldiers. They were trained on previously acquired English "Vickers". But even for one tank battalion, despite the presence of personnel, there were not enough tanks.

Therefore, 7 tanks that survived the unloading of the ship, along with 17 Vickers acquired in the UK, made up the Mobile Detachment, which included a tank squadron, a motorized infantry company (150 soldiers and officers, 16 armored trucks), reconnaissance platoon ( three armored cars), anti-tank artillery battery and mountain artillery battery. During the Japanese invasion of the territory of the Dutch Ost-India, the Mobile Detachment under the command of Captain G. Wulfhost, together with the fifth infantry battalion of the East India Army, engaged the Japanese 230 infantry regiment. Despite initial success, the Mobile Detachment eventually had to retreat, leaving 14 people dead, 13 tanks, 1 armored vehicles and 5 armored personnel carriers disabled. After that, the command redeployed the detachment to Bandung and no longer threw him into military operations until the surrender of the Dutch East Indies to the Japanese.

The Second World War

After the Netherlands was occupied by Hitler's Germany, the military and political situation of the Dutch East Indies began to deteriorate rapidly - after all, the channels of military and economic assistance from the metropolis were cut off, in addition to Germany, until the end of the 1930-s, which remained one of the key military - trading partners of the Netherlands, now, for obvious reasons, have ceased to be so. On the other hand, Japan, which has long been intending to "take possession" of practically the entire Asia-Pacific region, became active. The Japanese Imperial Navy delivered units of the Japanese Army to the shores of the islands of the Malay Archipelago.

The operation itself in the Dutch East Indies was quite swift. In 1941, Japanese flights began aviation over Borneo, after which units of Japanese troops invaded the island, which were assigned the goal of capturing oil enterprises. Then the airport was captured on the island of Sulawesi. A detachment of 324 Japanese defeated 1500 Marines of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army. In March 1942, battles for Batavia (Jakarta) began, which on March 8 ended with the surrender of the capital of the Dutch East Indies. General Poten commanded her defense capitulated along with a garrison of 93 men.

During the campaign 1941-1942. almost all of the East Indian army was defeated by the Japanese. Dutch soldiers, as well as soldiers and non-commissioned officers from a number of Christian ethnic groups in Indonesia, were interned in prison camps, and up to 25% of prisoners of war died. A small part of the soldiers, mostly from among the representatives of the Indonesian peoples, was able to go into the jungle and continue the guerrilla war against the Japanese invaders. Some units managed completely independently, without any assistance from the Allies, to hold out until the liberation of Indonesia from the Japanese occupation.

During the campaign 1941-1942. almost all of the East Indian army was defeated by the Japanese. Dutch soldiers, as well as soldiers and non-commissioned officers from a number of Christian ethnic groups in Indonesia, were interned in prison camps, and up to 25% of prisoners of war died. A small part of the soldiers, mostly from among the representatives of the Indonesian peoples, was able to go into the jungle and continue the guerrilla war against the Japanese invaders. Some units managed completely independently, without any assistance from the Allies, to hold out until the liberation of Indonesia from the Japanese occupation. Another part of the East Indian army was able to cross into Australia, after which it was joined to the Australian troops. At the end of 1942, an attempt was made to reinforce the Australian special forces, who were leading the partisan struggle against the Japanese in East Timor, by the Dutch soldiers from the East Indian army. However, the Dutch 60 perished in Timor. In addition, in 1944-1945. small Dutch units participated in the fighting in Borneo and the island of New Guinea. Under the operational command of the Australian Air Force, four squadrons of the Dutch East Indies were formed from among the pilots of the Royal Dutch East Indies Air Force and the Australian ground staff.

As for the Air Force, the Royal Dutch Ost-Indian Army aviation was initially seriously inferior to the Japanese in terms of equipment, which did not prevent the Dutch pilots from fighting adequately, defending the archipelago from the Japanese fleet, and then becoming part of the Australian contingent. During the battle for 19 Semplak on January 1942, the Dutch pilots on the 8 Buffalo aircraft fought 35 to Japanese aircraft. As a result of the collision, 11 Japanese and 4 Dutch aircraft were shot down. Among the Dutch asss should be noted Lieutenant August Deibel, who during this operation shot down three fighters of Japanese aircraft. Lieutenant Deybel managed to go through the whole war, survive after two wounds, but death found him in the air and after the war - in 1951, he died at the helm of a fighter plane in a plane crash.

When the East Indies army capitulated, it was the Dutch East Indies air force that remained the most combat-ready unit under the Australian command. Three squadrons were formed — two B-25 bomber squadrons and one Kittyhawk P-40 fighter squadron. In addition, three Dutch squadrons were created as part of British aviation. The British Air Force submitted the 320 and 321 squadrons and the 322 squadron bombers. The latter, up to the present, remains in the composition of the Netherlands Air Force.

The post-war period

The end of the Second World War was accompanied by the growth of the national liberation movement in Indonesia. Freed from the Japanese occupation, the Indonesians no longer wanted to return under the rule of the metropolis. The Netherlands, despite the convulsive attempts to keep the colony under its power, were forced to make concessions to the leaders of the national liberation movement. However, the Royal Dutch East Indian Army was restored and continued to exist for some time after World War II. Her soldiers and officers took part in two major military campaigns to restore the colonial order in the Malay Archipelago in 1947 and 1948. However, all the efforts of the Dutch command to preserve sovereignty on the Dutch East Indies proved futile and December 27 1949. The Netherlands accepted the recognition of Indonesia’s political sovereignty.

26 July 1950 was decided to disband the Royal Dutch East Indies Army. By the time the Royal Dutch East Indian Army was disbanded, 65 000 soldiers and officers were serving in the military. Of these, 26 000 was recruited into the Republican Indonesian Armed Forces, the remaining 39 000 was demobilized or transferred to service in the Armed Forces of the Netherlands. The native soldiers were given the opportunity to demobilize, or continue to serve in the armed forces of sovereign Indonesia.

However, here again inter-ethnic contradictions made themselves felt. In the new armed forces of sovereign Indonesia, Muslim-Javanese dominated - veterans of the national liberation struggle, always negatively related to Dutch colonization. In the colonial troops, the main contingent was represented by Christianized Ambonians and other peoples of the South Molluksky islands. Inevitable tensions arise between Ambonians and Javanese, which led to conflicts in Makassar in April 1950 and an attempt to create an independent Republic of Southern Molukks in July 1950. By November 1950, the Republican forces were able to suppress the performances of the Ambonians.

After that, more 12 500 Ambonians who served in the Royal Dutch East Indies Army, as well as their family members, were forced to emigrate from Indonesia to the Netherlands. Some Ambonians emigrated to Western New Guinea (Papua), which until the 1962 remained under the rule of the Netherlands. The ambonts who served the Dutch authorities for emigration were explained very simply - they feared for their life and security in postcolonial Indonesia. As it turned out, it was not for nothing: from time to time serious riots erupt in the Molluksky Islands, the cause of which almost always are conflicts of the Muslim and Christian population.

Information