Russia and Tibet: unsuccessful attempts at union

However, at the end of the 19th century, Russia succeeded in establishing dominance over Western Turkestan, which the British Empire strongly opposed, and also increased its influence in Outer Mongolia (the territory of modern sovereign Mongolia) and Outer Manchuria (modern south of the Far East). Gradually, the interests of the Russian state began to extend beyond the indicated lands.

In particular, Russia drew attention to the more southern regions of Central Asia inhabited by Muslim and Buddhist populations - Eastern Turkestan, Inner Mongolia and Tibet. We will try to tell about how Russian-Tibetan relations developed and what has turned out of these relations in this article. At least Russia, and then the Soviet Union, had an interest in Tibet for almost a century. And only the strengthening of the People's Republic of China, which included fully Tibetan territory, contributed to the final rejection of plans to include Tibet into the orbit of Russian / Soviet political influence.

It should be noted that in the Russian empire there existed a stratum of intelligentsia of the “indigenous” peoples, including Lamaist professors who considered themselves Buddhist and considered themselves akin to Tibetan Buddhists in religious and cultural terms. Many of these Buddhist intellectuals were agents of Russian influence in Central Asia and ardent supporters of the spread of Russian power to this region. First of all, they, of course, cared for the preservation of the unique culture of the Tibetan and Mongolian peoples, their religion, from the Manchu and, especially, British expansion.

Peter Badmaev: Russia, Mongolia and Tibet should unite

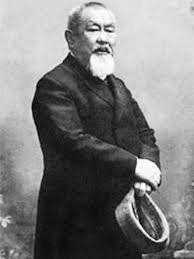

One of the pioneers of the idea of Russian expansion in the lands of Central Asia inhabited by Tibetans and Mongols was Peter Badmayev. The name of this person, Buryat by origin, indicates that he was not a Buddhist. At least - in his mature years: the son of a Buryat, a nomad who did not have much prosperity and political influence, Peter Badmaev, who became a doctor, accepted Orthodoxy of his own accord. His godfather was the emperor Alexander III himself. However, Badmaev’s biography is serious enough for a native of a distant Siberian people. In many respects, this was facilitated by the fact that Badmaev’s older brother, Alexander, was a doctor of traditional Buryat medicine and had a certain influence in government circles, making a protection for his younger brother to enter the Irkutsk Russian classical gymnasium. Its ending was for the younger Badmayev a “ticket” to the world of Russian science and politics.

Zhamsaran Badmaev, as Peter was called before his baptism, graduated with honors from the Eastern Faculty of St. Petersburg University - he studied Mongolia and Manchuria. The uncommon abilities of a young Buryat are indicated by the fact that he was simultaneously educated at the Military Medical Academy. In the 1875 year, immediately after graduation, Badmaev was employed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. With the imperial family, Badmaev became close, engaging in oriental medicine, which is popular among the “powerful of the world”. Peter treated Alexander III, Nicholas II, Tsarevich Alexei. In parallel, Badmayev owned a pharmacy of medicinal herbs, his own trading house, newspaper, mining and industrial partnership.

Zhamsaran Badmaev, as Peter was called before his baptism, graduated with honors from the Eastern Faculty of St. Petersburg University - he studied Mongolia and Manchuria. The uncommon abilities of a young Buryat are indicated by the fact that he was simultaneously educated at the Military Medical Academy. In the 1875 year, immediately after graduation, Badmaev was employed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. With the imperial family, Badmaev became close, engaging in oriental medicine, which is popular among the “powerful of the world”. Peter treated Alexander III, Nicholas II, Tsarevich Alexei. In parallel, Badmayev owned a pharmacy of medicinal herbs, his own trading house, newspaper, mining and industrial partnership. However, in the context of our article, Badmaev is interesting, first of all, as a specialist in Central Asian politics. He entered history with their insistent proposals to include Outer and Inner Mongolia and Tibet in the Russian Empire. For this, Badmayev proposed to complete the Trans-Siberian Railway to the Chinese province of Gansu, which bordered Tibet. This highway was to help Russia establish direct transport links with Tibet and bring pro-Russian elements there to power. Otherwise, Badmaev argued, the British Empire would come to Central Asia and Russia would then lose the economic and political positions to the British. According to Badmaev, by establishing Russian power over Tibet, the empire can not only strengthen its geopolitical position, but also take control of continental trade with China, Korea, and the countries of Southeast Asia. Significantly, Badmaev’s plans were supported by Finance Minister Sergei Witte, but Tsar Alexander III refused to implement the plans of his Buryat doctor.

The second hope of Peter Badmaev appeared already under the heir of Alexander III, Nicholas II. When Badmaev wrote to the emperor a memorandum in which he reported on the great significance of control over Tibet for the Russian empire, Nikolai became very interested in this issue and sent an expedition to Podesaul Ulanov to Tibet. The latter had to find out what is really happening in Tibet and how strong the British positions are there. However, Badmayev was unlucky for the second time - the Russian-Japanese war began and the authorities were not up to the Tibetan issue. Then came the First World Revolution. Badmayev was arrested and died in prison in 1920.

Travels of Gombozhab Tsybikov and Ovshe Norzunov

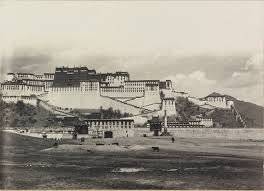

Research expeditions to the territory of Tibet began to be sent by the Russian side from the end of the 19th century, however, they did not reach the most closed central regions of the country, including its capital, Lhasa. Russian travelers of European nationality were seriously suspicious and were not allowed into Tibet. Therefore, the only way to get reliable information about the situation in Tibet was to send travelers from among the Buryats or Kalmyks. One of the most famous travels about which the nicest work was written, undertook in 1899-1902. Gombozhab Tsybikov is a famous Russian and Soviet orientalist, Mongolian and Buddhologist. He was also a representative of the nascent Buryat intelligentsia and was sent by his parents to the Aginsk parish school, and then to the Chita gymnasium, where he received a European education.

By the time the travel began, 26-year-old Tsybikov had time to study at the medical faculty at Tomsk State University, and then enter the Orientalist (by the way, on the advice of Peter Badmaev). Under the guise of a pilgrim in a group of pilgrims traveling from Buryatia to Lhasa, Tsybikov spent a journey of 888 days. Moreover, he was able to visit Lhasa and its main monasteries, filmed a unique photographic material (of course, the photographing was carried out secretly, otherwise Tsybikov could face the most serious sanctions, up to the death penalty). Honored Tsybikov and the audience of the Dalai Lama, though - as a pilgrim (the second time Tsybik had the honor to meet the Dalai Lama while the latter was in Urga - the capital of Outer Mongolia (now Ulan Bator) after fleeing the British invasion of Tibet in 1905) . After the end of the expedition, Tsybikov devoted himself to scientific activities and, unlike Badmaev, was not directly connected with politics. For a long time, he translated the Lamrim treatise, which was written by the founder of the Gelug-pa school Tsongkhavy, and headed the department of Mongolian literature at the Eastern Institute of Vladivostok and produced a unique “Manual for the Study of Tibetan Language”.

By the time the travel began, 26-year-old Tsybikov had time to study at the medical faculty at Tomsk State University, and then enter the Orientalist (by the way, on the advice of Peter Badmaev). Under the guise of a pilgrim in a group of pilgrims traveling from Buryatia to Lhasa, Tsybikov spent a journey of 888 days. Moreover, he was able to visit Lhasa and its main monasteries, filmed a unique photographic material (of course, the photographing was carried out secretly, otherwise Tsybikov could face the most serious sanctions, up to the death penalty). Honored Tsybikov and the audience of the Dalai Lama, though - as a pilgrim (the second time Tsybik had the honor to meet the Dalai Lama while the latter was in Urga - the capital of Outer Mongolia (now Ulan Bator) after fleeing the British invasion of Tibet in 1905) . After the end of the expedition, Tsybikov devoted himself to scientific activities and, unlike Badmaev, was not directly connected with politics. For a long time, he translated the Lamrim treatise, which was written by the founder of the Gelug-pa school Tsongkhavy, and headed the department of Mongolian literature at the Eastern Institute of Vladivostok and produced a unique “Manual for the Study of Tibetan Language”. Almost simultaneously with Tsybikov, Kalmyk Orsu Norzunov also visited Lhasa. Unlike Tsybikov, he visited Tibet three times. The first time - on the instructions of Aghvan Dorzhiev delivered in 1898-1899. letter to the Dalai Lama about the course of negotiations in St. Petersburg. The second time was in 1900, again on the initiative of Dorzhiev and, at the same time, the Russian Geographical Society. However, this time Norzunov was detained in India as a Russian agent and was stopped for several months in Darjeeling, where he lived in a monastery and was reported to the police, after which he was deported to the Russian Empire. The third trip to Tibet Norzunov undertook at the end of the same year 1900, surrounded by Dorzhiev, through Mongolia and Xinjiang. This time he managed to photograph Lhasa, after which Norzunov returned to Russia with Dorzhiev.

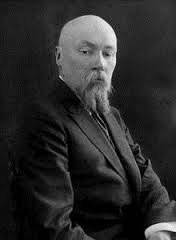

Agvan Dorzhiev: Pro-Russian Counselor of the Dalai Lama

In parallel with Badmayev, the question of including Tibet into the Russian Empire at the royal court was lobbied by Agvan Dorzhiev, another Buryat, unlike Badmaev, who made a serious career not at the Russian court, but surrounded by the Tibetan Dalai Lama Thirteenth. Agvan Dorzhiev was the approximate age-mate of Peter Badmaev in his age. He was born in 1853, in the village of Khara-Shibir, Khorinsky Office in the territory of modern Buryatia. Back in his youthful years, Dorzhiev traveled to Mongolia and Tibet. He managed to study at a Buddhist datsan in Urga, and then at the Goman Datsan of Drepung Monastery in the Tibetan capital Lhasa. If Badmayev was an Orientalist and a doctor, then Dorzhiev received a theological education and joined the seven scholars of lamas, who were advisers to the Dalai Lama. In addition to teaching the theological and secular head of Tibet theological disciplines, Aghvan Dorzhiev turned into an influential political figure of the country over time, being an adviser to the Dalai Lama on general political issues.

Obviously, it was precisely the Buryat origin of Dorzhiev that played a role in the fact that it was to him in 1898 that the Tibetan leadership entrusted the trip for information purposes to China, the Russian Empire and Europe. In St. Petersburg, Dorzhiev was personally introduced to Emperor Nicholas II. Returning to Tibet, Aghvan Dorzhiev was appointed to a position similar to the first minister of the court. From this time, Agvan Dorzhiev’s numerous trips around the world begin - he managed to visit China, Russia, India, Japan, Germany, Great Britain, and Italy. Russia has always been of paramount importance for Dorzhiev - he did not forget that it was in the Russian Empire that his Buryat tribesmen lived and saw in Russia a legitimate advocate for the interests of Central Asian Buddhists. He managed to achieve the opening of a Buddhist school in Kalmykia, a datsan and a publishing house in St. Petersburg.

At the court of the Dalai Lama, Dorzhiev was the main initiator of the development of relations with neighboring Russia. He managed to present the Russian Empire as the northern kingdom of Shambala, keeping faith in Buddhist teachings, and described Nicholas II as a reincarnation of Saint Tsongkhava, the founder of the Gelug-pa school and the reformer of the Lamaist tradition. To prove his words, Dorzhiev referred to the good living conditions of the Buryats, Tuvans and Kalmyks in the Russian Empire. Dorzhiev traveled to Russia several times, but failed to convince the emperor and his government to conclude a military alliance of the Russian Empire and Tibet.

Dorzhiev sought to get military aid to Tibet, rightly fearing a strengthening of British expansion in Central Asia. First of all, this was evidenced by the establishment of British supremacy in the Himalayas - Ladakh, Sikkim, which were considered traditional outposts of Tibetan religious and cultural influence in South Asia. Dorzhiev feared that Tibet would become the next target of British expansion and the traditional way of life of this unique country would be dealt a crushing blow.

However, in parallel with the projects of the Russian protectorate over Tibet, two other major players in Central Asia — the British Empire and Japan — did not refuse such plans. Both the British and the Japanese were very concerned about the growth of pro-Russian sentiment in Tibet and the efforts of Lama Dorzhiev to draw the attention of the Russian emperor to the Tibetan issue. Japanese and British agents visited Tibet and subsequently spread conflicting information about the situation in this country. Thus, the Japanese monk Ekai Kawaguchi, who formally traveled to the monasteries of Central Asia in search of rare religious treatises, actually played a role in spreading misinformation about Russian expansion into Tibet. So, he tried to convince the British of this, obviously trying to embroil Britain and Russia and, thus, benefit the situation in the interests of Japan.

To some extent, Kawaguchi's plans were successful - he convinced the British representative in Sikkim, Sir Charles Bell, and the viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, in the Russian expansion into Tibet. The latter, seeking to prevent Russia's final control over Tibet and a blow to the economic and political interests of England in the region, ordered the introduction of British troops into Tibet. As a result of the British expedition, the Dalai Lama and Dorzhiev fled to Outer Mongolia, and the Tibetan government, in the absence of its leader, signed an agreement recognizing the British protectorate over Sikkim, stationing a British diplomatic and military mission in Lhasa. In parallel, the British sought to prevent the expansion of Tibet’s contacts with Russia. During his next visit to the Russian Empire, Agvan Dorzhiev had to change into a beggar and go through Calcutta. A significant reward was announced for Agvan Dorzhiev’s head.

Since the conclusion of a British-Russian treaty on the political status of Tibet, which recognized China’s power over the country, followed in 1907, the Russian authorities began to distance themselves from undisguised interest in the Tibetan issue. After Chinese troops entered Tibet, the Dalai Lama fled to India, to Sikkim, where he established contacts with the British administration and fell under its influence.

Revolutions, Russia and Tibet

Meanwhile, the overthrow of the Manchu Qing dynasty in China had a major impact on Russian-Tibetan relations. The Chinese did not abandon the expansionist plans for Tibet, but the invasion of the Chinese troops was met with a major uprising, forcing the relatively weak Chinese army to withdraw from Tibet. Naturally, in the same period, the Dalai Lama again attempted to enlist the military support of Russia. In Russia, celebrations on the occasion of the 300 anniversary of the Romanov dynasty in 1913 were held in the Buddhist datsan of St. Petersburg. However, the Russian Empire with military help Tibet was in no hurry, as well as the British. The British did not want to spoil relations with China and were not going to accept Tibet as a fully sovereign state. Accordingly, the Tibetans turned for help to a third potential ally, Japan. The Japanese, who had long sought to strengthen their influence in the national regions of China - Mongolia, Manchuria, Tibet, did not refuse to help. A Japanese military adviser was sent to guide the modernization of the Tibetan army.

A new significant change in the political situation in Central Asia followed the February and October revolutions in Russia. A new state appeared - the Soviet Union, which invested a radically new ideology in its expansionist policy. For a long time, the Bolsheviks did not go to the deterioration of relations with the Buddhist clergy, and if in the Orthodox regions of the country the anti-church orientation was designated almost immediately, and during the Civil War was fully manifested, then against Buddhists, the Soviet regime at first was more supportive. Moreover, Lenin and his associates understood the significance of Buddhism for Asian societies and did not want to incite Buryats, Kalmyks, Tuvans, and Outer Mongolia against Soviet Russia.

However, the revival of interest in Tibet was associated with several other events. In 1921, the people's revolution led by Suhe-Bator won in Mongolia. The latter, with the help of Soviet troops, succeeded in destroying the White Guards of Baron Ungern von Sternberg and establishing control over the territory of Outer Mongolia. Understanding that it was still impossible to openly propagate communist ideas in Mongolia, Suhe-Bator and his associates at first engaged in establishing parallels between communism and Buddhist faith and convinced the Mongols that nothing terrible happened - the establishment of a communist regime does not mean “the end of the doctrine”, but only returns the latter to the original meaning.

Buddhism and communism, the OGPU and Roerich's expedition

The idea of common communist ideology and Buddhism was also widely spread among the Soviet political elite, especially among some OGPU workers. Even then, the Soviet special services realized the possibility of using this idea to establish control over the region of Central Asia. Therefore, there was practically open support for the expedition of such a person as Nicholas Roerich. Many researchers deny the intelligence and political meaning of his expedition, reducing it to purely scientific, artistic or mystical ("search for Shambhala") goals. However, one can hardly agree with that. The Soviet government did not have any reason to support Roerich’s expedition without unequivocal benefit for himself, especially considering that Roerich was not a scientist, but an artist and a theosophist, that is, sufficiently doubtful for official support of the character.

The well-known artist gradually moved to the pro-Soviet position and ranked Lenin among the great teachers of our time - the “mahatmas”, describing him as follows: “You can imagine that Lenin had already felt the immutability of the new structure without the slightest material basis. ... Monolithic thinking of fearlessness created Lenin's halo on the left and on the right .... Seeing the imperfection of Russia, one can accept much for the sake of Lenin, for there was no other who, for the common good, could accept a great deal. Not in proximity, but in all fairness, he even helped the cause of the Buddha ... Take Lenin's appearance as a sign of the sensitivity of the Cosmos ... ”(First Edition of the Community). It is hardly possible to call this position communist, sustained in the spirit of ideology that prevailed in the Soviet Union, but Nicholas Roerich did not become a victim of political repression.

The well-known artist gradually moved to the pro-Soviet position and ranked Lenin among the great teachers of our time - the “mahatmas”, describing him as follows: “You can imagine that Lenin had already felt the immutability of the new structure without the slightest material basis. ... Monolithic thinking of fearlessness created Lenin's halo on the left and on the right .... Seeing the imperfection of Russia, one can accept much for the sake of Lenin, for there was no other who, for the common good, could accept a great deal. Not in proximity, but in all fairness, he even helped the cause of the Buddha ... Take Lenin's appearance as a sign of the sensitivity of the Cosmos ... ”(First Edition of the Community). It is hardly possible to call this position communist, sustained in the spirit of ideology that prevailed in the Soviet Union, but Nicholas Roerich did not become a victim of political repression. From the point of view of the Bolshevik regime, he looked, to put it mildly, strange and in theory should have been counted as counter-revolutionaries for his mystical ideas. However, this did not happen. Roerich not only got the opportunity to make an expedition throughout Central Asia, but also enjoyed the support of the Soviet leadership. Although the artist called the search for Shambhala the official goal of the expedition, in reality she wore semi-intelligence targets. In this respect, the description of the journey by his son, an orientalist Yuri Roerich, looks more interesting than the work of Nicholas Roerich about traveling to Mongolia, Tibet and the Himalayas.

The Roerich expedition lasted from 1923 to 1929. For six years, the Roerichs and their followers walked from Altai to the Himalayas, visiting Mongolia, East Turkestan, Qinghai, Tibet, Sikkim, Ladakh. Throughout their journey, they were faced with a rather negative reaction of the Chinese and British authorities on their journey, since the latter rightly saw in it the interest of the Soviet leadership and special services. Naturally, the Bolsheviks did not have anyone to rely on in Tibet — the working class and the intelligentsia in the modern sense of the word were absent in the archaic Tibet.

The peasantry was a believing and fanatical polls, so it was possible to manipulate them, say, in the interests of the uprising and the establishment of the pro-Soviet regime only by referring to religion or religious-mystical teachings, including the same concept of the proximity of Buddhism and communism. At the same time, it was impossible to organize an uprising without the support of someone from the highest hierarchs of Tibetan Buddhism - it had to be either the Dalai Lama or the Panchen Lama. Accordingly, it was necessary to enlist the sympathies of one of the supreme lamas and use it to their advantage. For this role, the Panchen Lama was more suitable, since the Dalai Lama had long held pro-English and pro-Japanese positions, sought to modernize the Tibetan army and hardly expected, despite the position of Dorzhiev and other Soviet Buddhist hierarchs, to cooperate with the Soviet Union.

In order to attract the attention of Buddhist hierarchs to the Soviet Union and the communist ideology, Roerich used the old concepts of Pan-Mongolism and Eurasianism, referring to the common Russian, Turkic-Mongolian, Tibetan civilizations and insisting on the vital necessity of their mutual cooperation. At the same time, the revolutionary renewal of the Buddhist regions of Central Asia, according to Roerich, should have meant a return to the original meanings of Buddhism, the very “Shambhala”.

Roerich's expedition is often associated with the name of Jacob Blumkin - one of the iconic figures on the "eastern fronts" of Soviet intelligence, a very remarkable person in many respects. Despite his young years (1900 year of birth, that is, 25-27 years to the time of the events described), Blumkin was a prominent figure of the Soviet special services. And he began his active political activities not as a Bolshevik, but as a member of the Party of Left Socialist Revolutionaries, from which he was delegated to serve in the Cheka in 1918. At the age of 18, he was appointed head of the counterintelligence department to monitor the security of embassies and their possible criminal activities. He participated in the famous assassination of Ambassador Mirbach. He visited Iran, where he participated in the creation of the Gilani Soviet Republic, was wounded several times. Then he commanded the 61 th brigade of the Red Army, which fought against the army of Baron Ungern. At the same time, Blumkin did not shy away from secular bohemian life, he had a close acquaintance with many Russian poets of those years.

It was Blumkin in 1926 that became the representative of the OGPU and the main instructor of the state security of Mongolia. That is, played a key role in the Central Asian direction of Soviet foreign policy. In 1926-1927 Blumkin served as a military advisor to the Chinese general Feng Yuxiang. The well-known historian O. Shishkin, who wrote the book Battle for the Himalayas, claims that Blumkin was directly involved in the Roerich expedition itself, posing as a Buddhist monk. However, other researchers are inclined to refute this version, which, again, does not exclude the possibility of the participation of other representatives of the Soviet special services in the Roerich Central Asian Expedition.

After Roerich returned from the expedition, the interest of the Soviet special services to Tibet did not subside. The OGPU outfitted two trips to Lhasa (in 1926 and 1928) of its Asian-looking agents, Kalmyks, who pretended to be pilgrims and followers to monasteries in Tibet. The agents of the OGPU met with the Dalai Lama, offering him guarantees of Tibet’s political sovereignty in exchange for cooperation with the Soviet authorities. It is significant that Agvan Dorzhiev, about whom we wrote above, has returned to this idea. The famous figure of Tibetan Buddhism was in the Soviet Union and actively participated in the activities of Soviet Buddhists, seeking to promote the community of Buddhism and communist ideology and on this basis to “renew” Soviet Buddhism, to give it a slightly different dimension than before. Although, apparently, he simply accepted the Soviet Union as the heir to the Russian empire and expressed pro-Russian sentiments, albeit looking like an attempt to synthesize Buddhist religious philosophy with Soviet communist ideology.

The path to the end of the Soviet-Tibetan history

In 1927, the first All-Union Congress of Buddhists of the USSR was held, at which Agvan Dorzhiev openly declared a community of Buddhism and communism. At the same time, Dorzhiev again tried to convince the Dalai Lama that Soviet Russia is Shambhala, Lenin is almost a Buddhist, and Buddha was the first communist on earth. Initially an active role in the “renewal” of Soviet Buddhism was played by the OGPU, for whom the figure of Agvan Dorzhiev was extremely convenient in terms of influencing the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan authorities, searching for opportunities to organize a pro-Soviet state in Tibet under religious banners.

The situation changed after the strengthening of the regime of Joseph Stalin. The latter "put" on completely different actors in Asian politics - above all, on the Chinese Communist Party. In 1929, the Buddhist church was banned in Buryatia, in 1935, in Leningrad, where, by 1937, it was possible to actually defeat the Buddhist community at the temple that existed since tsarist times. In November 1937 of the year, despite his “renovation” positions, Agvan Dorzhiev was also arrested. A year later, he died in the hospital of Ulan-Ude Prison - for the 85-year-old monk, the arrest was a serious blow to his health and attitude. In parallel with the Soviet Union, repression against the Buddhist clergy followed in the "vassal" Mongolian People's Republic and Tannu-Tuva People's Republic.

The victory of the Chinese Communist Party in the civil war and the establishment of Chinese power over Tibet finally put an end to the aspirations of Russia and the early Soviet Union to create a controlled regime in Tibet. Modern Russia, not wanting to aggravate relations with China, also does not pay much attention to the Tibet issue, preferring to ignore it. For a long time, the Dalai Lama, who lives in India and advocates for the independence of Tibet, is not allowed to enter the Russian Federation, although the Buddhists living in Russia - the peoples who traditionally profess Lamaism (Buryats, Kalmyks, Tuvans), as well as Russians who turned to Buddhism and representatives of other nations of the country.

Information