The Forgotten Malay War: How Communists Fought Against the British Commonwealth

In the post-war period, the “people's armies”, largely controlled by the communist parties, did not put down weapon, and continued the armed struggle - this time against the colonialists or anti-communist forces. In China, North Korea and North Vietnam, this struggle ended with the advent of the communist parties to power, and in Southeast Asia, it was dragged out for many decades. One of the longest and largest armed confrontations unfolded in the then British protectorate of Malaya (now Malaysia) and was called the “Malay War”. Over the years 12 - from 1948 to 1960. the armed forces of the countries of the British Commonwealth - Britain, Australia and New Zealand, as well as the protectorate police, opposed the Communist Party of Malaya and its armed forces, which led the struggle for the liberation of the country from the power of the British colonialists.

British malaya

The Malay Peninsula, as well as the adjacent islands of the Malay Archipelago, are inhabited by Malays and related peoples belonging to the Austronesian language family (along with the peoples of Indonesia, the Philippines, and the islands of Oceania). At the beginning of AD. in Malacca, the first state formations are already taking shape; by the middle of the 15th century, the adoption of Islam by the rulers of the Malay states. When in the XVI-XVII centuries. Melaka was interested in the European powers - first Portugal, and then the Netherlands and Great Britain; feudal states vied with each other — the sultanates headed by the sultans, who were also called rajas — adjoined in the peninsula.

The presence of the British on the Malacca Peninsula began when, in 1819, the representative of the East India Company, Thomas Raffles, signed an agreement with the Sultan of Johor to establish a commercial zone under the British control in the islands that now form the city-state of Singapore. In 1867, Singapore became a colony of the British Empire, and in 1874, the British forced the ruler of the Sultanate of Perak to enter into a protectorate agreement with them. Soon, the sultanates of Selangor, Negri-Sembilan and Pahang also became protectorates of the British Empire. Somewhat later, under the British protectorate, Sabah was found in the north-east of Kalimantan Island (Borneo), and after World War II, Sarawak.

The presence of the British on the Malacca Peninsula began when, in 1819, the representative of the East India Company, Thomas Raffles, signed an agreement with the Sultan of Johor to establish a commercial zone under the British control in the islands that now form the city-state of Singapore. In 1867, Singapore became a colony of the British Empire, and in 1874, the British forced the ruler of the Sultanate of Perak to enter into a protectorate agreement with them. Soon, the sultanates of Selangor, Negri-Sembilan and Pahang also became protectorates of the British Empire. Somewhat later, under the British protectorate, Sabah was found in the north-east of Kalimantan Island (Borneo), and after World War II, Sarawak.By the time of the outbreak of World War II, British Malaya consisted of several parts: the Straits-Setments colony of Singapore, the Penang Islands, the Wellesley province, and the Malacca region; The Malay Federation (Federated States of Malaya) comprising the Sultanates of Perak, Selangor, Negri-Sembilan and Pahang; the non-federated northern sultanates of Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan and Terengganu and the southern sultanate of Johor. In fact, all the power and decision-making in these state entities was in the hands of the representatives of the British crown - residents in the sultanates of the Malay Federation and advisers in the sultanates who were not included in the federation.

Malaya’s difference from other regions of Southeast Asia was a comparatively small number of indigenous people — the Malays do not make up more than half of the local population, the rest are Chinese and Indian migrants who came to the peninsula at various times in search of work. It was the Chinese that already in the prewar period made up the bulk of not only merchants (the Chinese are called Jews of Southeast Asia for their business success), but also of the working class.

The Malays by nationality in the colony and the sultanates were feudal aristocracy and peasants. Accordingly, peasants who did not want to work in industrial enterprises remained in rural areas, while cities and workers' settlements were settled by Chinese traders and workers. The Chinese also dominated tin mines - tin remained one of the most important exports of British Malaya. Another group of alien populations — Indians, primarily Telugu and Tamils — worked in the production of rubber.

It was among the Indians that the Marxist circles of the Communist Party of the South Seas arose, on the basis of which the Communist Party of Malaya (KPM) was created in 1930. The Communist Party operated in the territory of Malaya, Singapore, as well as in neighboring Thailand and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), where there were no communist parties of their own. The CPM maintained contacts with the Comintern and periodically fell under the hard pressure of the British colonial administration. In 1931, its strength was estimated at 1500 activists and around 10 000 sympathizers. Gradually, the party increased the number of Chinese, who made up the majority of the skilled workers in Malaya. When Japan invaded China in 1937, a rapprochement between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party began on the basis of anti-Japanese solidarity. In the countries of settlement of the Chinese diaspora, which included Malaya and Singapore, the cooperation of local Kuomintang and Communists was also established, as a result of which a significant part of the Kuomintang supporters moved to the ranks of the Communist Party.

Anti-Japanese Army of the Peoples of Malaya

The second world war the British Malaya met with fierce battles of the British troops with the Japanese invaders. In the end, the Japanese managed to seize the territory of the Malay peninsula, and even Singapore, which was considered the main British military base in the region. Malaya was divided into ten provinces headed by Japanese generals or colonels. In many respects, it was the consequences of the Japanese occupation of Malaya, which lasted from 1942 to 1945, that laid the socio-economic prerequisites for the activation of the communist partisan movement in this British colony.

First of all, the Japanese administration undertook to reorganize the ethnosocial pyramid in Malacca. The Malays, formerly at the bottom of the social hierarchy (except aristocrats), were declared close to the Japanese and occupied the upper floors of the social ladder, freed from the escape of the British. The Chinese, formerly considered the most privileged group of the population, during the Japanese occupation turned into an oppressed group, while the Japanese preferred not to quarrel with the Indians, expecting to use the Indians in the future as allies against the British in India itself.

Secondly, the basis of the economy of Malaya - mining of tin and production of rubber - has suffered the most serious damage during the Japanese occupation. Equipment mining industry was sent to the smelter, and plantations withered without proper guidance. The Chinese workers, who had previously worked in tin mines and processing enterprises, had no choice but to go to the jungle, occupying land uninhabited by the Malays and trying to farm. The total number of such forest settlers was up to 500 thousand people. Among them were communists - members of the Communist Party of Malaya, including those who fled to the jungle after the Japanese seized Singapore.

Interacting with the former workers of the tin industry, the Communists launched a massive anti-Japanese agitation. 15 February 1942 began the armed attacks of the Communists against the occupying Japanese troops. In the mountainous regions of the Perak Sultanates — in the north of Malaya, and Johor — in the south — armed groups were formed, which were united in the Anti-Japanese Army of the Peoples of Malaya. The number of the Anti-Japanese Army reached 7 thousands of people and, despite the fact that its name spoke of a multinational composition, in fact most of the soldiers and commanders of the army were Chinese. There were significantly fewer Indians, while the Malays, although present, were in a clear minority. In cities and rural areas, the Anti-Japanese Army of the Peoples of Malaya was supported by the Anti-Japanese Union of Malaya, which united up to 300 thousands of people.

The units of the Anti-Japanese Army of the Peoples of Malaya were commanded by the Central Military Committee of the Communist Party of Malaya in Pahang. In turn, district military committees of the party submitted to him. For the partisan war in the sultanates were responsible separate units that carried out and agitation among the civilian population. The anti-Japanese army was also unique in that it had its own military schools. Two-month courses of the Central Military Committee were created in Pahang, and the People’s Academy in Johor.

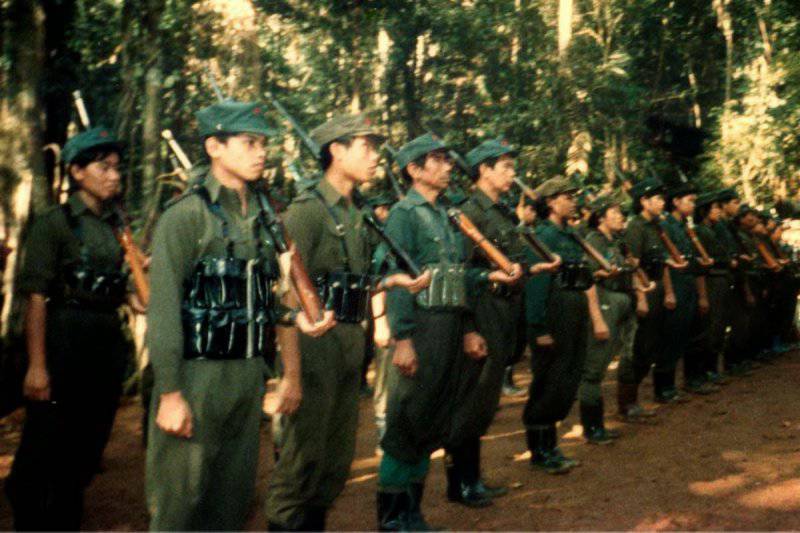

It is significant that the Anti-Japanese Army of the Peoples of Malaya was distinguished by a high degree of organization and had the structure and discipline of a regular army. In many ways, this was achieved thanks to the natural discipline of the Chinese, who formed the backbone of the army, as well as the efforts of the communists, who determined the ideological line of the partisan movement. An extensive network of partisan bases and training camps was created in the mountainous regions, and underground groups were established in the cities. The effective organization of the Anti-Japanese Army led to the fact that as early as 1943, it controlled not only the mountain areas of Perak and Johor, but also almost the entire territory of Malaya outside urban centers and large villages.

It is significant that the Anti-Japanese Army of the Peoples of Malaya was distinguished by a high degree of organization and had the structure and discipline of a regular army. In many ways, this was achieved thanks to the natural discipline of the Chinese, who formed the backbone of the army, as well as the efforts of the communists, who determined the ideological line of the partisan movement. An extensive network of partisan bases and training camps was created in the mountainous regions, and underground groups were established in the cities. The effective organization of the Anti-Japanese Army led to the fact that as early as 1943, it controlled not only the mountain areas of Perak and Johor, but also almost the entire territory of Malaya outside urban centers and large villages. The British military command tried to subjugate the partisan movement, but to no avail, so the British had no choice but to support the Anti-Japanese army materially and informationally, without having any real influence on it. The beginning of 1945 was marked by the transition of the Anti-Japanese Army to active hostilities in the Sultanate of Johor, by the summer the partisans managed to liberate a number of settlements. In addition to the territory of the Malacca Peninsula, the fighters of the Anti-Japanese Army managed to influence the situation in the north of Kalimantan Island - in Sabah and Sarawak, where partisan units were also created.

During the fighting, the Anti-Japanese Army destroyed more than 10 thousands of Japanese soldiers and 2,5 thousands of their accomplices from among the representatives of the local population. Japan’s capitulation at a time when there were no British forces in Malaya was a real gift for the Anti-Japanese Army. It was the command of the Anti-Japanese Army that accepted the surrender of the Japanese units remaining in Malaya. The partisans who occupied the city, began to attempt social arrangements for post-war Malaya. Politically, they were guided by the nine points of the anti-Japanese struggle program adopted in February 1943, which provided for the creation of a Malay Democratic Republic after the expulsion of the occupiers.

When the Japanese capitulated, and the territory of Malaya was controlled by the troops of the Anti-Japanese Army that actually liberated it, the British colonialists returned to the Peninsula, landing an expeditionary force of 250 thousands of people. Naturally, with him the partisans could not afford. The anti-Japanese army began negotiations with the British, agreeing on the partial demobilization of the personnel of its units and the dissolution of the established people's committees. However, 7 September 1945. The Communist Party of Malaya put forward six demands on England, aimed at creating a Malay Democratic Republic. Naturally, the British authorities did not respond to the communists, and in May 1946 the activities of the Communist Party of Malaya were officially banned.

Realizing that the situation had changed, and the battle ahead of yesterday’s temporary allies, the British forces, the leadership of the Communist Party of Malaya began to modernize its structure. In November, 1946 formed the All-Malaysian Joint Action Council, later renamed the United Popular Front, which, in the opinion of the communists, was supposed to unite all anti-colonial forces into a single movement. This, however, did not happen - largely due to the ideological differences of the Communists and their allies on the front. In fact, the opposition to the revival of British colonial rule was carried out by the Communist Party of Malaya.

"Emergency" in Malay

To renew the guerrilla struggle in the territory of Malaya, the Communists created the Liberation Army of the Peoples of Malaya. Initially, it numbered 4000 fighters, among which roughly 1000 were members of the Communist Party of Malaya. The social composition of the Liberation Army was mainly proletarian — more than 50% were skilled workers who had worked in the field of tin production and processing before the war. It is indicative that about 10% of the fighters of the Liberation Army were women - the Communists paid great attention to the equalization of the rights of men and women, with the goal of which they willingly accepted into the armed groups women workers and relatives of men - partisans. Organizationally, the Liberation Army of the Peoples of Malaya consisted of 10 regiments. Nine regiments were completely Chinese in ethnic composition, staffed by Chinese tin industry workers. The tenth regiment was mixed and included both Chinese and Indians and Malays.

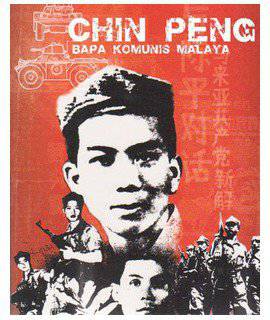

From 1947, the permanent leader of the Communist Party of Malaya was Chin Pen (1924-2013). Wang Wenhua, who was called Chin at birth, was born in the town of Sitawan in the Sultanate of Perak, in the family of a Chinese immigrant who was engaged in a small business of repairing bicycle tires and spare parts. At the age of thirteen, the future guerrilla leader, who studied at the local Chinese school, joined the secret society, which set as its goal the liberation of Chinese territory from the Japanese invaders. For some time he studied in the Methodist English-speaking school, then he abandoned it and focused entirely on revolutionary activities. In 1939, Mr. Chin Pen became a supporter of communist ideas, and at the end of January, 1940, at the age of 15, was accepted as a candidate member of the Communist Party of Malaya. During the Second World War, like many of his fellow tribesmen and like-minded people, Chin Pen went to the partisans.

From 1947, the permanent leader of the Communist Party of Malaya was Chin Pen (1924-2013). Wang Wenhua, who was called Chin at birth, was born in the town of Sitawan in the Sultanate of Perak, in the family of a Chinese immigrant who was engaged in a small business of repairing bicycle tires and spare parts. At the age of thirteen, the future guerrilla leader, who studied at the local Chinese school, joined the secret society, which set as its goal the liberation of Chinese territory from the Japanese invaders. For some time he studied in the Methodist English-speaking school, then he abandoned it and focused entirely on revolutionary activities. In 1939, Mr. Chin Pen became a supporter of communist ideas, and at the end of January, 1940, at the age of 15, was accepted as a candidate member of the Communist Party of Malaya. During the Second World War, like many of his fellow tribesmen and like-minded people, Chin Pen went to the partisans. The capable young man was quickly appreciated by the leadership of the communist underground and appointed a liaison officer of the Anti-Japanese Army of the Peoples of Malaya, communicating with the British military command. May 24 A group of five Chinese led by British captain John Davis was landed from a submarine in Malacca in May 1943. Chin Pen established contact with this group and subsequently coordinated the partisans' interaction with the British, who helped the Anti-Japanese Army with weapons. By this time, 18-year-old Chin Pen was already secretary of the Malaya Communist Party in the Sultanate of Perak. After the war, the merits of Chin Pena in the liberation of Malaya from the Japanese were recognized even by the British. Guerrilla commander and communist participated in the Victory Parade in London, was awarded the Burmese Star, the Order of the British Empire and the Star 1939-1945.

In the same period, the party suffered a serious blow - Secretary-General Lai Tek, regarding whom even during the war years there were serious suspicions about his cooperation with the enemy, fearing exposure, fled the country, taking with him the party fund. After the secretary general of the CPM Central Committee, Lai Tek, was exposed as a betrayal as an agent of the Japanese and British intelligence services at the same time, Chin Pen, who was considered the most devoted party and active leader, was elected the new general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Malaya and remained for the rest of his life.

In 1948, three British planters were killed. Having accused the communists of this crime, the British authorities introduced a state of emergency in Malaya. The Communist Party responded with a real transition to hostilities, having achieved the greatest success in 1950-1951. In particular, the High Commissioner for Malaya Henry Gerney was killed. A long guerilla war began, in which the Liberation Army and the 13-thousandth Communist Party of Malaya, which had among its activists 00 thousands of armed militants - underground fighters, were opposing the armed forces of Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand, which expanded to 150 40. 250 thousands of British, 40 thousands of Australian and New Zealand military personnel and Malay police units totaling up to 60 thousand people were concentrated against the partisans.

At the same time, the Malay War bore the character of a classic partisan war. Her story does not know of positional battles, large-scale armed clashes. As a rule, the confrontation was carried out through the "guerrilla group - division or platoon of the British marines or other units of the armed forces of the British Commonwealth". The British, observing the success of the communists in Vietnam and Korea, in turn, tried to do everything possible to prevent the communists from coming to power in Malaya. In opposition to the Communist Party of Malaya, the British authorities used not only military methods, but also political and socio-economic solutions.

First of all, the British began to win the sympathy of the Malay population. Since the guerrilla movement was almost completely Chinese, it was not popular with the Malay population. The Malay peasants practically did not go to the partisan detachments and, at least voluntarily, did not render them any support. The British emphasized this, supporting the Malaysian peasants with provisions and medicines and in every possible way demonstrating their friendly attitude to them. As a result, the Chinese who had gone into the jungle had to act almost without relying on the villagers - Malays, which had a very negative impact on the logistics of the partisan army. The second strategic decision of the British, in addition to supporting the Malay population, was the resettlement of the Chinese into “new villages”, under the control of the British military. By this, the colonial authorities also wanted to cut off the potential social base of the partisans.

Finally, it was in Malaya that British troops began to use special anti-partisan and counter-sabotage tactics of warfare - the search and destruction of partisan groups by small special forces units - “hunters”. Nevertheless, the armed struggle of the Liberation Army of the Peoples of Malaya continued throughout the 12 years - from 1948 to 1960. During this time, 6800 guerrillas, 520 British, 810 Australian and New Zealand military personnel and 1350 Malay policemen were killed. As for the wounded, from the side of the communists their number is estimated at 5300 people, the British army - 1200 people, the Australian and New Zealand armies - 2500 people, the Malay police - 2500 people.

In 1957, wishing to finally secure themselves against the seizure of power by the Communists, Great Britain took the extreme step of providing the state sovereignty of the Malay Federation as part of the 9 sultanates and the 2 provinces. Nevertheless, the fighting continued, although the army of communists, exhausted by the years of war, had only 1500 partisans hiding in the mountainous regions of the northern sultanates. 31 July 1960 was officially announced to end the state of emergency. The same date is considered to be the date of the end of the Malay War.

Red partisans of Malaya and North Kalimantan

However, the proclamation of independence of the Malay Federation and the end of the state of emergency did not mean the surrender of the Malay Communists. Although in fact resistance was suspended, the Communist Party gathered strength and healed wounds. Moreover, in the 1960-e years there was a "Maoist turn" of the Malaysian Communists. At this time, China, which had grown stronger, turned its attention to the countries of Southeast and South Asia, hoping to establish friendly regimes in them or, at least, to create hotbeds of the Maoist movement. To this end, serious work was begun to attract the Communists of India, Indochina and the Malay Archipelago to the Maoist positions. As a result, the communist parties in Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines fell under the influence of China.

Chin Pen - the leader of the Malaysian communists - by this time he himself moved to China, from where he carried out 2000 leadership of the remaining communists and partisan detachments of total number of 500 people who were based in the mountains on the border of Malaysia and Thailand. In 1969, in the Chinese province of Hunan, the Malaysian and Singapore-oriented KPM radio station “Voice of the Malay Revolution”, broadcasting before 1981, was launched. In the same 1969, in response to another intensification of the Vietnam War, the Communist Party of Malaysia resumed fighting in the border areas from both the Malaysian and Thai sides. In 1970, on the territory of Southern Thailand, the Communist Party of Malaya (Marxist-Leninist), splinter from the Communist Party of America, began its military operations.

[

For many years, it was the jungles of southern Thailand that became the shelter of the guerrillas of the Communist Party of Malaya. Here, the communists recruited the Malay population (as you know, several provinces of southern Thailand are populated including ethnic Malays), and also moved to a new tactic - to attract the sympathy of the Malay population, convinced of their infringement in Buddhist Thailand, the communists began to distribute leaflets about the similarity ideas of communism and Islam. On the territory of Southern Thailand and in the border area, the Communist Party of Malaya led military operations until 1989.

In parallel, the hostilities of the communist partisans were carried out in two Malay states located in the north of the island of Kalimantan (Borneo) - Sarawak and Sabah. Here, the communist movement also originates from Chinese migrants who moved to the north of Kalimantan in the 1920's - 1930's. During the Second World War in North Kalimantan, the Anti-Japanese League of North Borneo and the Anti-Japanese League of Western Borneo led guerrilla actions against the Japanese invaders. After the independence of the Malay Federation was proclaimed, the Communists, who were active in the north of the island of Kalimantan, opposed the entry of the Sarawak and Sabah territories into the Malay Federation. This was due to differences in the historical development, ethnic composition of the population and the cultural specifics of the territories of North Kalimantan. The communists advocated “self-determination of the peoples of North Kalimantan,” although here the majority of the activists of the communist movement were Chinese, and the indigenous people — ibans, melanau and other Dayak tribes (Dayaks — the collective name of the peoples of Kalimantan island, both in its Malay and Indonesian parts) - as a rule, did not participate in active political activity.

In 1960-s. in North Kalimantan, the People’s Army of North Kalimantan and the Saravak People’s Partisans were created on the basis of the youth communist organizations, two armed organizations focused on guerrilla warfare against Malaysian government forces. The Saravak people's partisans were formed on 30 in March on 1964 in West Kalimantan by Chinese students of political origin who fled to the jungle from political persecution. Their numbers reached 800 people, headed by Yang Zhu Chun and Wen Min Chuang. From the very beginning of its activities, the Saravak guerrillas collaborated with the Communist Party of Indonesia, a small group of partisans trained in China. The People's Army of Northern Kalimantan was formed on October 26 by 1965 by a commander named Bong Ki Chok, focusing on combat operations in the eastern part of Sarawak.

The guerrillas of Sarawak once enjoyed direct support from the Indonesian special services, interested in weakening the Malaysian presence in Kalimantan. Thus, at the beginning of its activities, the Saravak guerrilla units even had Indonesian officers or non-commissioned officers of the marine commando corps or paratroopers of the air force as instructors. The military coup of General Suharto in 1965, which overthrew the power of the pro-Soviet Sukarno, put an end to Indonesia’s cooperation with the communists of Sarawak. However, the latter continued to fight against the Malaysian, and then the Indonesian, troops until November 1990. 30 March 1970 was formed by the Communist Party of North Kalimantan, which for twenty years led the armed resistance of partisan detachments in Sarawak.

The beginning of the collapse of the socialist camp was the final one for the Malay communists who had fought in the mountains and jungles of the Malacca Peninsula for more than forty years. 2 December 1989 in the city of Had Yai in southern Thailand Chin Pen signed peace agreements between the Communist Party of Malaya and the governments of Malaysia and Thailand. However, Malaysia did not allow the former militants of the Communist Party to return to the country and they settled in the "peaceful villages" in southern Thailand.

Chin Pen himself lived in Thailand until his death in 2013, at the age of 88. In 2006, while Chin Pena was still alive, Malay director Amir Muhammad directed his film The Last Communist, which was banned from being shown in Malaysia (even possession of a disc with this film in Malaysia is punishable by law, although in fact it is only a biographical film telling about the life and fate of the permanent leader of the Malay Communists, how he decided on a long-term armed confrontation - first with the countries of the British Commonwealth, and then with sovereign Malaysia).

Information